Building Historical Consciousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

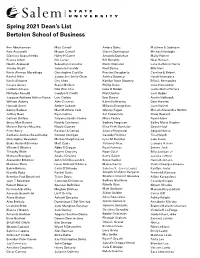

Spring 2021 Dean's List Bertolon School of Business

Spring 2021 Dean’s List Bertolon School of Business Ben Abrahamson Matt Carroll Ambra Doku Matthew S Gubitose Kyle Acciavatti Megan Carroll Gianni Dominguez Michael Hakioglu Gianluca Acquafredda Haley H Carter Amanda Donahue Molly Hamer Bianca Adam Nic Carter Bill Donalds Neal Hansen Noelle Alaboudi Sebastian Carvalho Daniel Donator Lana Kathleen Harris Jimmy Alcott Gabriela Cassidy Fiori Dorne Billy Hart Kevin Aleman Maradiaga Christopher Castillo Preston Dougherty Caroline E Hebert Rachel Allen Jacqueline Emily Chan Ashley Downey Handi Henriquez Kevin Almonte City Chen Katelyn Rose Downey Erika L Hernandez Cesare Aloise Stone M Chen Phillip Dube Julio Hernandez Luidwin Amaya Nok Wan Chu Luke D Dudek Leslie Maria Herrera Nicholas Ansaldi Carolyn R Cinelli Nick Dunfee Jack Hobbs Jayquan Anthony Arthur-Vance Lexi Ciolino Erin Dwyer Austin Holbrook William Aubrey Alex Cisneros Katie Eleftheriou Dom Hooven Hannah Aveni Amber Cokash Mikayla Evangelista Luan Horjeti Sonny Badwal Max Matthew Cole Wesley Fagan Miriam Alexandra Horton Jeffrey Baez Ryan Collins Art Fawehinmi Drew Howard Colleen Balfour Tatyana Conde-Correa Miles Feeley Ryan Huber Siena Mae Barone Nayely Contreras Sydney Ferguson Bailey Marie Hughes Melane Barrios-Macario Nicole Cooney Elise Firth-Gonzalez Geech Huot Peter Barry Rachael A Corrao Ariana Fitzgerald Abigail Hurley Zacharie Joshua Beauchamp Connor Corrigan Cassidy Fletcher Tina Huynh Christopher Beaudoin Michael Ralph Cosco Lynn M Fletcher Jake Irvine Blake Holland Benway Matt Coyle Yulianny Frias Leonora A Ivers Vikram S Bhamra Abby S Crogan Ryan Fuentes Steven Jack Timothy Blake Rupert Crossley Noor Galal Billy Jackson Jr Marissa Blonigen Anabel Cruzeta Kerry Galvin Jessica Jeffrey Alexander Bloomer John G D’Alessandro Steve Garber Hannah Jensen Madison Blum Louis Richard D’Amico Mateo Garcia Quelsi Georgia Jimenez Babin Bohara Carly D’Orlando Sabrina Y. -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/23/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket

CJUS8023 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/23/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Thursday Trial Date: 9/23/2021 8:30:00 AM Docket #: 1825414 Defendant: ANDERSON , QUINTON LAMAR Charge: DOMESTIC ASSAULT Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: SMITH, BRIAN #996, Complaint #: A 132063 2021 Arrest Date: 5/14/2021 Docket #: 1793448 Defendant: APPLEBERRY , BRANDON JAMAL Charge: AGGRAVATED ASSAULT Presiding Judge: WEBB, GERALD Division: 3 Court Room: 3 Arresting Officer: GOULET, JOSEPH #385, Complaint #: A 62533 2021 Arrest Date: 5/26/2021 Docket #: 1852403 Defendant: ATCHLEY , GEORGE FRANKLIN Charge: CRIMINAL TRESPASSING Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: SIMON, LUKE #971, Complaint #: A 100031 2021 Arrest Date: 9/17/2021 Docket #: 1814264 Defendant: AVERY , ROBERT CAMERON Charge: THEFT OF PROPERTY Presiding Judge: WEBB, GERALD Division: 3 Court Room: 3 Arresting Officer: SERRET, ANDREW #845, Complaint #: A 091474 2020 Arrest Date: 9/9/2020 Docket #: 1820785 Defendant: BALDWIN , AUNDREA RENEE Charge: CRIMINAL TRESPASSING Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Court Room: 1 Arresting Officer: FRANTOM, MATTHEW #641, Complaint #: M 115725 2020 Arrest Date: 11/14/2020 Docket #: 1815168 Defendant: BARBER , JUSTIN ASHLEY Charge: OBSTRUCTING HIGHWAY OR OTHER PASSAGEWAY Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: LONG, SKYLER #659, Complaint #: A 094778 2020 Arrest Date: 9/18/2020 Docket #: 1812424 Defendant: BARNES -

CA Students Urge Assembly Members to Pass AB

May 26, 2021 The Honorable Members of the California State Assembly State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Thousands of CA Public School Students Strongly Urge Support for AB 101 Dear Members of the Assembly, We are a coalition of California high school and college students known as Teach Our History California. Made up of the youth organizations Diversify Our Narrative and GENup, we represent 10,000 youth leaders from across the State fighting for change. Our mission is to ensure that students across California high schools have meaningful opportunities to engage with the vast, diverse, and rich histories of people of color; and thus, we are in deep support of AB101 which will require high schools to provide ethnic studies starting in academic year 2025-26 and students to take at least one semester of an A-G approved ethnic studies course to graduate starting in 2029-30. Our original petition made in support of AB331, linked here, was signed by over 26,000 CA students and adult allies in support of passing Ethnic Studies. Please see appended to this letter our letter in support of AB331, which lists the names of all our original petition supporters. We know AB101 has the capacity to have an immense positive impact on student education, but also on student lives as a whole. For many students, our communities continue to be systematically excluded from narratives presented to us in our classrooms. By passing AB101, we can change the precedent of exclusion and allow millions of students to learn the histories of their peoples. -

Skins Uk Download Season 1 Episode 1: Frankie

skins uk download season 1 Episode 1: Frankie. Howard Jones - New Song Scene: Frankie in her room animating Strange Boys - You Can't Only Love When You Want Scene: Frankie turns up at college with a new look Aeroplane - We Cant Fly Scene: Frankie decides to go to the party anyway. Fergie - Glamorous Scene: Music playing from inside the club. Blondie - Heart of Glass Scene: Frankie tries to appeal to Grace and Liv but Mini chucks her out, then she gets kidnapped by Alo & Rich. British Sea Power - Waving Flags Scene: At the swimming pool. Skins Series 1 Complete Skins Series 2 Complete Skins Series 3 Complete Skins Series 4 Complete Skins Series 5 Complete Skins Series 6 Complete Skins - Effy's Favourite Moments Skins: The Novel. Watch Skins. Skins in an award-winning British teen drama that originally aired in January of 2007 and continues to run new seasons today. This show follows the lives of teenage friends that are living in Bristol, South West England. There are many controversial story lines that set this television show apart from others of it's kind. The cast is replaced every two seasons to bring viewers brand new story lines with entertaining and unique characters. The first generation of Skins follows teens Tony, Sid, Michelle, Chris, Cassie, Jal, Maxxie and Anwar. Tony is one of the most popular boys in sixth form and can be quite manipulative and sarcastic. Michelle is Tony's girlfriend, who works hard at her studies, is very mature, but always puts up with Tony's behavior. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS DIVISION OF INSURANCE PRODUCER LICENSING 1000 Washington Street, Suite 810 Boston, MA 02118-6200 FAX (617) 753-6883 http://www.mass.gov/doi Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021 License # Licensure Individual Address City State Zip Phone # 1 007408 01/01/1977 Abate, Andrew Suffolk AutoBody, Inc., 25 Merchants Dr #3 Walpole MA 02081 0-- 0 2 014260 11/24/2003 Abdelaziz, Ilaj 20 Vine Street Lexington MA 02420 0-- 0 3 013836 10/31/2001 Abkarian, Khatchik H. Accurate Collision, 36 Mystic Street Everett MA 02149 0-- 0 4 016443 04/11/2017 Abouelfadl, Mohamed N Progressive Insurance, 2200 Hartford Ave Johnston RI 02919 0-- 0 5 016337 08/17/2016 Accolla, Kevin 109 Sagamore Ave Chelsea MA 02150 0-- 0 6 010790 10/06/1987 Acloque, Evans P Liberty Mutual Ins Co, 50 Derby St Hingham MA 02018 0-- 0 7 017053 06/01/2021 Acres, Jessica A 0-- 0 8 009557 03/01/1982 Adam, Robert W 0-- 0 West 9 005074 03/01/1973 Adamczyk, Stanley J Western Mass Collision, 62 Baldwin Street Box 401 MA 01089 0-- 0 Springfield 10 013824 07/31/2001 Adams, Arleen 0-- 0 11 014080 11/26/2002 Adams, Derek R Junior's Auto Body, 11 Goodhue Street Salem MA 01970 0-- 0 12 016992 12/28/2020 Adams, Evan C Esurance, 31 Peach Farm Road East Hampton CT 06424 0-- 0 13 006575 03/01/1975 Adams, Gary P c/o Adams Auto, 516 Boston Turnpike Shrewsbury MA 01545 0-- 0 14 013105 05/27/1997 Adams, Jeffrey R Rodman Ford Coll Ctr, Route 1 Foxboro MA 00000 0-- 0 15 016531 11/21/2017 Adams, Philip Plymouth Rock Assurance, 901 Franklin Ave Garden City NY 11530 0-- 0 16 015746 04/25/2013 Adams, Robert Andrew Country Collision, 20 Myricks St Berkley MA 02779 0-- 0 17 013823 07/31/2001 Adams, Rymer E 0-- 0 18 013999 07/30/2002 Addesa, Carmen E Arbella Insurance, 1100 Crown Colony Drive Quincy MA 02169 0-- 0 19 014971 03/04/2008 Addis, Andrew R Progressive Insurance, 300 Unicorn Park Drive 4th Flr Woburn MA 01801 0-- 0 20 013761 05/10/2001 Adie, Scott L. -

South Texas Project Units 3 & 4 COLA

Rev. 07 STP 3 & 4 Environmental Report 2.3.2 Water Use This section describes surface water and groundwater uses that could affect or be affected by the construction or operation of two Advanced Boiling Water Reactors (ABWR) units, STP 3 & 4, at the STP site. Included are descriptions of the types of consumptive and nonconsumptive water uses, identification of their locations, and quantification of water withdrawals and returns. 2.3.2.1 Surface Water The surface water bodies that are within the hydrologic system in which the STP site is located, and that may affect or be affected by the construction and operation of STP 3 & 4, include streams and surface water drainage features within the southeastern- most section of the Colorado River Basin in Matagorda County. Although the Tres Palacios River is less than 10 miles (16 kilometers) west of the STP site, surface water flow westward from the STP 3 & 4 (Figures 2.3.1-1 and 2.3.1-7) construction area would not reach the Tres Palacios River because this flow would be intercepted by Little Robbins Slough and flow southward toward Matagorda Bay. Therefore, the Tres Palacios River basin is not discussed further in this section. The Colorado River is more than 865 miles long and has an annual flow of 1,904,000 acre-feet per year. The Colorado River Basin extends over 42,318 square miles with 39,428 square miles of the basin existing within the state of Texas (Reference 2.3.2- 1). There are 32 reservoirs within the Colorado River Basin, with a total conservation storage capacity of 4,472,705 acre-feet and a total potential release capacity of 478,667 acre-feet per year (Reference 2.3.2-1). -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

2021 Gangsome Summary

2021 Gangsome Summary Overall Skins Leaderboard Overall Gangsome Rankings 1) Jake Clodfelter – 8 - Includes Bonus Tournament Performance 2) Gary Pugh – 6 - Top Players will be named team captains & receive 3) Lee Everhart - 4 free entry into the 1st Annual Holly Ridge Ryder Cup – 3) Pearson Parks 4 September 2021 5) Justin Stanley – 3 5) Nick Welshons – 3 1) Jake Clodfelter +19.33 5) Barry Briggs – 3 2) Gary Pugh +12.5 5) Nick Cromer – 3 3) Nick Cromer +9.0 9) Andy Routh – 2 4) Lee Everhart +8.25 9) Brandon Berrier - 2 5) Justin Stanley +8.0 9) Austin Rickard - 2 6) Pearson Parks +6.25 9) Jeff Jensen – 2 7) Nick Welshons +6.08 9) Shane Conti – 2 8) Shane Conti +6.0 9) Josh Spell – 2 9) Russ Patterson +5.58 9) Joe Burchette – 2 10) Kevin Pennala +4.75 9) Curtis Brotherton – 2 11) Clint Harrison +4.33 9) Charles Mackintosh – 2 12) Wes Tyner +4.0 18) Kevin Pennala – 1 13) Rahim Stennett +3.33 18) Kevin Spencer – 1 14) Tim Williams +3.25 18) Danny Kovach – 1 14) Barry Briggs +3.25 18) Rahim Stennett – 1 16) Zach Lax +3.0 18) Anthony Baker – 1 17) Jeff Jensen +2.75 18) Jonathan Franklin – 1 17) Curtis Brotherton +2.75 18) Zach Lax – 1 19) Justin Rickard +2.58 18) Jeff Eddins – 1 20) Brandon Berrier +2.5 18) Phillip Reece – 1 20) Nick Lewis +2.5 18) Tanner Gross – 1 20) Charles Mackintosh +2.5 18) Chris Grove – 1 20) Tanner Gross +2.5 18) Dan East – 1 20) Josh Spell +2.0 18) Tim Williams – 1 20) Austin Rickard +2.0 18) Dewayne Blakely – 1 20) Scott Daniels +2.0 18) Dylan Laviner – 1 20) Andy Routh +2.0 18) Spanky Goodyear – 1 20) Phillip Reece -

Skins and the Impossibility of Youth Television

Skins and the impossibility of youth television David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays, can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In 2007, the UK media regulator Ofcom published an extensive report entitled The Future of Children’s Television Programming. The report was partly a response to growing concerns about the threats to specialized children’s programming posed by the advent of a more commercialized and globalised media environment. However, it argued that the impact of these developments was crucially dependent upon the age group. Programming for pre-schoolers and younger children was found to be faring fairly well, although there were concerns about the range and diversity of programming, and the fate of UK domestic production in particular. Nevertheless, the impact was more significant for older children, and particularly for teenagers. The report was not optimistic about the future provision of specialist programming for these age groups, particularly in the case of factual programmes and UK- produced original drama. The problems here were partly a consequence of the changing economy of the television industry, and partly of the changing behaviour of young people themselves. As the report suggested, there has always been less specialized television provided for younger teenagers, who tend to watch what it called ‘aspirational’ programming aimed at adults. Particularly in a globalised media market, there may be little money to be made in targeting this age group specifically. -

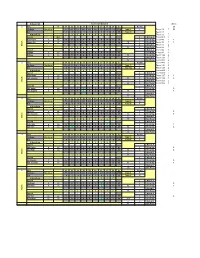

Week 6 Scorecard

5/13/2021 Scorecard (Back 9) Skins 1 Hole In 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points 13 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #1 7 Team #1 7 33 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #7 Team #7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #2 7 Team #1 -17 Net 2 Match A Team #21 2 Nick Fischer 1 38 4 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 5 39 1 Show Up Team #3 2 1 h c Deacon Jim 2 37 4 5 4 5 4 4 4 4 5 39 78 1 Show Up Team #5 7 1 t a -1 3 2 Match B Team #6 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 75 1 Net Total Team #8 7 Team #7 -1 1 1 1 1 4 Match A Team #4 5 A-Player 5 35 5 6 4 4 5 3 4 4 5 40 Show Up Team #9 4 B-Player 6 35 5 5 5 4 5 3 5 4 4 41 81 Show Up Team #12 4 -1 1 1 1 1 4 11 Match B Team #20 5 78 Net Total Team #13 4 2 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Team #15 5 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #2 7 Team #14 5 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #21 2 Team #19 4 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #16 2 Team #2 -9 2 Match A Team #18 7 Kerry Brown 7 34 5 6 5 5 4 4 5 3 4 41 1 Show Up Team #17 6 1 h c Tom Jennings 8 34 4 5 5 4 5 3 7 3 6 42 83 1 Show Up Team #22 3 1 t a -9 1 1 15 2 Match B Team #23 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 68 1 Net Total Team #24 1 Team #21 -9 Match A Phil Hoefert 7 38 6 6 5 4 5 4 5 5 5 45 1 Show Up 1 Gary Osborne 7 34 5 7 5 3 5 4 4 4 4 41 86 1 Show Up 1 -11 14 Match B 72 Net Total 3 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #3 2 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #5 7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #3 -23 Match A Steve Hill 2 41 4 5 6 5 5 4 7 3 4 43 1 Show Up 1 h c Mike