External Validation of a Mobile Clinical Decision Support System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product ID Product Type Product Description Notes Price (USD) Weight (KG) SKU 10534 Mobile-Phone Apple Iphone 4S 8GB White 226.8

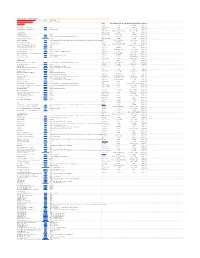

Rm A1,10/F, Shun Luen Factory Building, 86 Tokwawan Road, Hong Kong TEL: +852 2325 1867 FAX: +852 23251689 Website: http://www.ac-electronic.com/ For products not in our pricelist, please contact our sales. 29/8/2015 Product Price Weight Product Type Product Description Notes SKU ID (USD) (KG) 10534 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 4S 8GB White 226.8 0.5 40599 10491 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB Black Slate 486.4 0.5 40557 10497 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB Gold 495.6 0.5 40563 10494 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB White Silver 487.7 0.5 40560 10498 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 32GB Gold 536.3 0.5 40564 11941 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 128GB Gold 784.1 0.5 41970 11939 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Gold 622.8 0.5 41968 11936 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Silver 633.3 0.5 41965 11942 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Space Grey 618.9 0.5 41971 11940 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Gold 705.4 0.5 41969 11937 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Silver 706.7 0.5 41966 11943 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Space Grey 708 0.5 41972 11963 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 128GB Silver 917.9 1 41991 11955 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 16GB Gold 755.3 1 41983 11961 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 16GB Silver 731.6 1 41989 11958 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 16GB Space Grey 735.6 1 41986 11956 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 64GB Gold 843.1 1 41984 11962 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 64GB Silver 841.8 1 41990 11959 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 64GB Space Grey 840.5 1 41987 12733 mobile-phone ASUS ZenFone 2 ZE550ML Dual SIM -

BCVA Cover LZ.1.1

TWO DAY AUCTION, OUR LAST SALES AT BAYNTON ROAD WEDNESDAY 29th and THURSDAY 30th AUGUST BOTH COMMENCING AT 10.00AM LOTS TO INCLUDE: DAY ONE LOTS 1- 407 • SEIZED GOODS, TECHNOLOGY DAY TWO LOTS 408 - 981 • UNCLAIMED PROPERTY • FRAGRANCES AND TOILETRIES • ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO • CLOTHING AND SHOES • JEWELLERY, WATCHES AND GIFTS • HAND TOOLS AND SHIPPING CONTAINER • SPORTS AND LEISURE ITEMS • MEDICAL ACCESSORIES • MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS ON VIEW TUESDAY 28th AUGUST 10.30AM TO 6PM WEDNESDAY 29th AUGUST 9AM TO 6PM AND FROM 9am ON MORNINGA OF SALES Estimates are subject to 24% Buyers Premium (inclusive of VAT), plus VAT (20%) on the hammer price where indicated with an * asterick CATALOGUE £2 YOU CAN BID LIVE ONLINE FOR THIS AUCTION AT I-BIDDER.COM BCVA Asset Valuers & Auctioneers @BCVA_AUCTION Bristol Commercial Valuers & Auctioneers - The Old Brewery, Baynton Road, Ashton, Bristol BS3 2EB United Kingdom tel +44 (0) 117 953 3676 fax +44 (0) 117 953 2135 email [email protected] www.thebcva.co.uk IMPORTANT NOTICES We suggest you read the following guide to buying at BCVA in conjunction with our full Terms & Conditions at the back of the catalogue. HOW TO BID To register as a buyer with us, you must register online or in person and provide photo and address identification by way of a driving licence photo card or a passport/identity card and a utility bill/bank statement. This is a security measure which applies to new registrants only. We operate a paddle bidding system. Lots are offered for sale in numerical order and we usually offer approximately 80-120 lots per hour. -

Contratos Menores Servicios Y Suministros 2019

24/05/2019 04:48 PM UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA Página 1 de 238 Código del Objeto contrato Descripción de Código del Nombre del proveedor Primer apellido del Segundo Importe neto Alta expediente tipo contrato proveedor proveedor apellido del proveedor 2019/PRV000001 adquisición de revistas por medio de suscripción BIBLIOTECA. W0322079E LM TIETOPALVELUT OY 161.215,02 24/01/2019 SUSCRIPCIÓN SUCURSAL EN ESPAÑA Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 2019/PRV000002 SUSCRIPCIÓN REVISTAS PAPEL BIBLIOTECA. IT03106600483 CASALINI LIBRI, s.p.a. 46.051,68 24/01/2019 SUSCRIPCIÓN Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 2019/PRV000006 SUSCRIPCIÓN REVISTAS ELECTRÓNICAS BIBLIOTECA. B58583568 SERVEIS PEDAGOGICS, 3.500,00 08/02/2019 SUSCRIPCIÓN S.L. (GRAO) Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 2019/PRV000008 SUSCRIPCIÓN PAQUETE DE REVISTAS BIBLIOTECA. GB461600084 IOP PUBLISHING LTD IOP PUBLISHING 41.918,00 21/02/2019 ELELCTRÓNICAS: IOPSCIENCE EXTRA SUSCRIPCIÓ N LTD 2019* Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 2019/PRV000009 SUSCRIPCIÓN REVISTAS. SE ADJUNTA BIBLIOTECA. B82947326 MARCIAL PONS 58.163,51 26/02/2019 RELACIÓN SUSCRIPCIÓN LIBRERO, S.L. Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 24/05/2019 04:48 PM UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA Página 2 de 238 Código del Objeto contrato Descripción de Código del Nombre del proveedor Primer apellido del Segundo Importe neto Alta expediente tipo contrato proveedor proveedor apellido del proveedor 2019/PRV000010 Renovación Suscripción a la base de datos Core BIBLIOTECA. B84184217 GARTNER ESPAÑA,S.L. 24.000,00 12/03/2019 Research Reference (01/2019-12/2019) SUSCRIPCIÓN Y ACCESO A BASE DE DATOS DE REVISTAS 2019/PRV000011 SUSCRIPCIÓN A PAQUETE DE REVISTAS BIBLIOTECA. -

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

Gl Name Subcatdesc Asin Ean Description Qty Unit Retail

GL NAME SUBCATDESC ASIN EAN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT RETAIL PC Consumer Laser Printers B01N2MT6LX 632983042465 Kyocera Ecosys P3060dn SW-Laserdrucker (drucken bis zu 60 Seiten/Minute, 1.200 dpi) 1 995,67 Sports Electrostimulation B00NBB2S0K 5051752303005 Compex SP 4.0 Electrostimulateur Noir 1 629,00 Automotive Alloy Rims B01MRUDUCX 4250683759351 Oxigin 18 Concave 10.00 x 22 Offset 40 Bolt Pattern 5.00 x 114.30 Centre Bore 72.60 OXACHTZE1022J40BFPHD,1 604,94 Black Full Polish Automotive Alloy Rims B01MRUDUCX 4250683759351 Oxigin 18 Concave 10.00 x 22 Offset 40 Bolt Pattern 5.00 x 114.30 Centre Bore 72.60 OXACHTZE1022J40BFPHD,1 604,94 Black Full Polish Automotive Alloy Rims B01MRUDUCX 4250683759351 Oxigin 18 Concave 10.00 x 22 Offset 40 Bolt Pattern 5.00 x 114.30 Centre Bore 72.60 OXACHTZE1022J40BFPHD,1 604,94 Black Full Polish Office Product Binders and Binding Systems B0016Z6BH4 4056203498355 Fellowes 5622501 Profi DrahtbindegerâšÂ§t Galaxy-E Wire platin/anthrazit 1 527,82 Automotive Engine & Drivetrain B076HHNVY2 4005108994417 Luk 600 0230 00 Sets para Embrague 1 521,02 Sports Sports Watches B07D5LFR85 6417084500922 SUUNTO 9 Baro, Orologio Multisport, con Cintura FC Unisex – Adulto, Nero, Taglia Unica1 519,00 Lawn and Garden Water Preservation & Cleaning B01NAL921D 9317545022475 Zodiac Elektrischer Poolroboter TornaX OT 2100, Boden, FâšÂşr Folie, Polyester und Beton, WR0000941 519,00 Automotive Drivetrain, Engine & TransmissionB00KSKETKY 4250280933895 Honeywell Garrett Werkstauschlader 709836-9005S Original Werkstauschlader von Honeywell -

Pos-MAIL September 2010

WILLKOMMEN AUF DER IFA! WILLKOMMEN AUF DER IFA! WILLKOMMEN AUF DER IFA! September 2010 ISSN 1615 - 0635 • 5,– € 11. Jahrgang • 51612 INFORMATIONEN FÜR HIGH-TECH-MARKETING http://www.pos-mail.de HDluxe. Mit einem klaren Bekenntnis zum Entertainment in dergabe“, erklärte Michael Langbehn, Manager PR, Der neue Loewe der dritten Dimension stellt Panasonic auf der IFA CSR, Trade Marketing Communication Panasonic Individual. Erleben Sie die Loewe die Weichen für den 3D-Massenmarkt. „Wir zeigen Deutschland. „Von Camcordern über Blu-ray-Play- Produkt-Highlights auf unserem Stand die gesamte Bandbreite der er bis zum Fernseher und zu kompletten Blu-ray auf der IFA 2010 in faszinierenden Einsatzmöglichkeiten dieser revo- Heimkino-Systemen zeigt Panasonic neue Produk- Berlin. Halle 6.2 / lutionären Technik, von der Aufnahme bis zur Wie- te entlang der gesamten 3D-Signalkette.“ Stand 201. Neben neuen 3D-Fernsehern der besonderer Blickfang ist zudem ersten 3D-Camcorder der Con- in den Handel kommen, begleitet VT20-Serie, deren 50-Zoll-Modell das mit 152“ (385 cm) Bild- sumer-Klasse wird das Panasonic von einem Vielfachen an Spielen. soeben mit dem EISA Award aus- schirmdiagonale größte Full- Portfolio für die dritte Dimension „Zudem werden überall auf der gezeichnet wurde, kommt mit HD Plasma-Display der Welt. komplett. Welt Sport-Großereignisse in 3D dem multimedialen Alleskönner Mit neuen Blu-ray-Systemen und Auch um Content brauchen sich aufgenommen“, betont Ralf Han- GT20 jetzt auch ein Einstiegsmo- Soundbars für das Heimkino, 3D- die Endkunden keine Sorgen zu sen, Leiter Kommunikation/CE dell mit 42“ (106 cm) Bildschirm- Zubehör für die Systemkameras machen, denn bis Weihnachten Planning der Panasonic Deutsch- diagonale auf den Markt. -

Regulamin Promocji „Niedziela Okazji! - Kody Rabatowe”

Regulamin promocji „Niedziela okazji! - kody rabatowe” §1 Definicje Określenia użyte w niniejszym regulaminie oznaczają: 1. Organizator – TERG S.A. z siedzibą w Złotowie, przy ul. Za Dworcem 1D, 77-400 Złotów, wpisana do Krajowego Rejestru Sądowego Sądu Rejonowego Poznań - Nowe Miasto i Wilda w Poznaniu, IX Wydział Gospodarczy Krajowego Rejestru Sądowego pod nr KRS 0000427063, której nadano numer identyfikacyjny NIP 767-10-04-218, o kapitale zakładowym w wysokości 38 250 000 zł, w całości opłaconym. 2. Produkt promocyjny – jeden z modeli produktów wprowadzanych do obrotu przez Organizatora na terytorium Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, oznaczonych symbolem „Niedziela okazji z kodem rabatowym” opisane w załączniku nr 1. 3. Kod rabatowy – ciąg znaków, po wpisaniu którego w procesie składania zamówienia, cena produktu objętego promocją, ulega obniżeniu; 4. Uczestnik – pełnoletnia osoba fizyczna, posiadająca pełną zdolność do czynności prawnych, mająca miejsce zamieszkania na terytorium Polski, dokonująca zakupu produktu w charakterze konsumenta w rozumieniu art. 221 KC (Za konsumenta uważa się osobę fizyczną dokonującą z przedsiębiorcą czynności prawnej niezwiązanej bezpośrednio z jej działalnością gospodarczą lub zawodową). 5. Strona internetowa – strona WWW o adresie https://www.mediaexpert.pl/lp,niedziela-okazji utrzymywana przez Organizatora w celu bieżącej obsługi promocji oraz komunikacji z Uczestnikiem w sprawach dotyczących promocji. §2 Postanowienia ogólne 1. Promocja prowadzona jest na zasadach określonych niniejszym regulaminem. 2. Promocja prowadzona jest na terytorium Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej w okresie od 2018-03-18, godz. 00:00 do dnia 2018-03-18, godz. 23:59 lub do wyczerpania zapasów. 3. W promocji nie mogą uczestniczyć osoby będące pracownikami Organizatora, a także członkowie rodzin tych pracowników. Za członków rodziny uznaje się małżonka, wstępnych, zstępnych, rodzeństwo oraz osoby pozostające w stosunku przysposobienia. -

Gl Name Subcatdesc Asin Ean Description Qty Unit Retail

GL NAME SUBCATDESC ASIN EAN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT RETAIL Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B06VZ3Y2K4 4242003806067 Siemens TI917531DE EQ.9 s700 Kaffeevollautomat (1500 Watt, maximales1 Aroma,1762,50 2 BohnenbehâšÂ§lter, vollautomatische Dampfreinigung, Baristamodus, sehr leise, iAroma) edelstahl Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B07GS8TCZY 4242003827888 Siemens TI9575X1DE EQ.9 s700 plus connect Kaffeevollautomat (15001 Watt,1699,00 vollautomatische Dampfreinigung, Baristamodus, Home Connect, sehr leise, iAroma) edelstahl Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B01MU7WDX4 10942217558 Krups EA9010 Kaffee-Vollautomat One-Touch-Funktion (1,7 L, 15 bar, 1Touchscreen-Display,1483,93 MilchbehâšÂ§lter) silber Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B074QL4W4K 4242003806340 Siemens EQ.6 Plus s700 TE657503DE Kaffeevollautomat (1500 Watt, Keramik-mahlwerk,1 754,95 Touch-Sensor-Direktwahltasten, personalisierte GetrâšÂ§nke, Doppeltassenbezug) edelstahl Major Appliances Electric Hobs/Cooktops B016IGUBH6 4242004190806 Neff TTT1906N / T19TT06N0 / Autarkes Kochfeld / Konventionell / 90cm1 / TwistPad708,75 Flat / Zweikreis Major Appliances Bi Full Size Fridges B00BBWMDHE 5999024847843 Dometic DS 601 H freistehender KâšÂşhlschrank 52 l weiâšĂĽ 1 696,70 Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B074QL4W4K 4242003806340 Siemens EQ.6 Plus s700 TE657503DE Kaffeevollautomat (1500 Watt, Keramik-mahlwerk,1 684,95 Touch-Sensor-Direktwahltasten, personalisierte GetrâšÂ§nke, Doppeltassenbezug) edelstahl Kitchen Espresso Fully Automatic B074QL4W4K 4242003806340 Siemens EQ.6 Plus s700 -

117Electronics.Pdf

GL NAME SUBCATDESC ASIN EAN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT RETAIL Office Product Original Inkjet Cartridges B07B4LPKGF 4005039657009 Reflecta DigitDia 7000 10000 x 10000DPI, Nero, Bianco 1 2112,79 Office Product Cash Register & POS Paper Rolls B018DRQ9PG 8717496334688 Safescan 2685-S - High-Speed BanknotenzâšÂ§hler mit WertzâšÂ§hlung1 fâšÂşr855,28 gemischte Geldscheine, mit 7-facher FalschgeldprâšÂşfungbanknote - 100%ige Sicherheit Office Product Cash Register & POS Paper Rolls B018DRQ3EI 8717496334640 Safescan 2665-S - High-Speed BanknotenzâšÂ§hler mit WertzâšÂ§hlung1 fâšÂşr653,30 gemischte Geldscheine, mit 7-facher FalschgeldprâšÂşfungbanknote - 100%ige Sicherheit PC Business Inkjet Printers B00TAS2DOO 4058154044407 Canon PIXMA PRO-10S Stampante Multifunzione Inkjet Wi-Fi 4800 x 24001 dpi,643,89 Nero PC Cables B004Y3FNQA 4710423777446 Aten KH1516AI 16-Port Single User CAT5 IP KVM 1 556,04 PC Business Inkjet Printers B075D52LLF 8715946638966 Epson EcoTank ET-7750 3-in-1 Tinten-MultifunktionsgerâšÂ§t (Kopie, Scan,1 Druck,539,00 A3, 5 Farben, Fotodruck, Duplex, WiFi, Ethernet, Display, USB 2.0), Tintentank, hohe Reichweite, niedrige Seitenkosten PC Business Laser Printers B01N9BGGI7 632983042496 Kyocera P3045DN Imprimante Laser âšâ€ LED 1102T93NL0 A4/Duplex/LAN/Mono1 472,41 PC Business Laser Printers B01N3TFQI0 632983040331 Kyocera Ecosys M2540dn SW Multifunktionsdrucker, Multifunktionssystem1 Drucken,470,68 Kopieren, Scannen, Faxen, mit Mobile-Print-UnterstâšÂştzung fâšÂşr Smartphone und Tablet, schwarz-weiâšĂĽ PC Consumer Laser Printers B01MYSNUA3 -

Product ID Product Type Product Description Notes Price (USD

Rm A1,10/F, Shun Luen Factory Building, 86 Tokwawan Road, Hong Kong TEL: +852 2325 1867 FAX: +852 23251689 Website: http://www.ac-electronic.com/ For products not in our pricelist, please contact our sales. 22/8/2015 Product Price Weight Product Type Product Description Notes SKU ID (USD) (KG) 10534 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 4S 8GB White 221.5 0.5 40599 10487 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5c 32GB Green 378.9 0.5 40553 10491 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB Black Slate 489 0.5 40557 10497 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB Gold 514 0.5 40563 10494 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 16GB White Silver 490.4 0.5 40560 10498 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 32GB Gold 580.8 0.5 40564 10496 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 5s 64GB White Silver 554.6 0.5 40562 11941 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 128GB Gold 794.6 0.5 41970 11938 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 128GB Silver 798.5 0.5 41967 11944 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 128GB Space Grey 795.9 0.5 41973 11939 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Gold 622.8 0.5 41968 11936 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Silver 639.9 0.5 41965 11942 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 16GB Space Grey 617.6 0.5 41971 11940 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Gold 710.7 0.5 41969 11937 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Silver 710.7 0.5 41966 11943 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 64GB Space Grey 710.7 0.5 41972 11957 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 128GB Gold 950.6 1 41985 11963 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 128GB Silver 917.9 1 41991 11960 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 128GB Space Grey 969 1 41988 11955 mobile-phone Apple iPhone 6 Plus 16GB Gold 742.1 -

US 2016/0117541 A1 Lu Et Al

US 201601 17541A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0117541 A1 Lu et al. (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 28, 2016 (54) MUT FINGERPRINT ID SYSTEM Related U.S. Application Data (71) Applicant: THE REGENTS OF THE (60) Provisional application No. 61/846,925, filed on Jul. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNLA, 16, 2013. Oakland, CA (US) Publication Classification (72) Inventors: Yipeng Lu, Davis, CA (US); David (51) Int. Cl Horsley, Albany, CA (US); Hao-Yen we Tang, Berkeley, CA (US); Bernhard G06K9/00 (2006.01) Boser, Berkeley, CA (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .................................... G06K9/0002 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 14/896,150 (57) ABSTRACT (22) PCT Filed: Jul. 14, 2014 MEMS ultrasound fingerprint ID systems are provided. (86). PCT No.: PCT/US1.4/46557 Aspects of the systems include the capability of detecting both epidermis and dermis fingerprint patterns in three S371 (c)(1), dimensions. Also provided are methods of making and using (2) Date: Dec. 4, 2015 the systems, as well as devices that include the systems. Patent Application Publication Apr. 28, 2016 Sheet 1 of 12 US 2016/0117541 A1 - - - - - - - -3 a. s. sers c s re X------------ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Patent Application Publication Apr. 28, 2016 Sheet 2 of 12 US 2016/0117541 A1 re a was w w m w w m me we ree mere w .C. N s Y. r & r - a "a w Patent Application Publication Apr. 28, 2016 Sheet 3 of 12 US 2016/0117541 A1 Saw, w, . Patent Application Publication Apr. 28, 2016 Sheet 4 of 12 US 2016/0117541 A1 Patent Application Publication Apr. -

GL NAME SUBCATDESC ASIN EAN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT RETAIL Camera Bags & Cases B079945RDH 6958265159770 DJI Mavic Air Fly More

GL NAME SUBCATDESC ASIN EAN DESCRIPTION QTY UNIT RETAIL Camera Bags & Cases B079945RDH 6958265159770 DJI Mavic Air Fly More Combo - Drohne mit 4K Full-HD Videokamera inkl. Fernsteuerung1 907,94 I 32 Megapixel BilderqualitâšÂ§t und bis 4 km Reichweite - WeiâšĂĽ Office Product Labeling Systems B0047V2OLQ 4030152735808 Olympia 947730580 NC 580 GeldzâšÂ§hlgerâšÂ§t 1 814,66 Beauty B07JZPQ2QT 5025155037249 Dyson Airwrap Smooth+Control Multi Styler 1 566,68 Beauty B07JZPQ2QT 5025155037249 Dyson Airwrap Smooth+Control Multi Styler 1 566,66 Office Product Desktop Files & Storage B019ZF58OS 8717496335241 Safescan 2465-S - BanknotenzâšÂ§hler fâšÂşr gemischte Geldscheine, mit 7-facher1 FalschgeldprâšÂşfung530,19 PC Business Inkjet Printers B075DBF43N 8715946638942 Epson EcoTank ET-7700 3-in-1 Tinten-MultifunktionsgerâšÂ§t (Kopie, Scan, Druck,1 A4, 5483,95 Farben, Fotodruck, Duplex, WiFi, Ethernet, Display , USB 2.0), Tintentank, hohe Reichweite, niedrige Seitenkosten Personal Care Appliances Magnetic & Electrotherapy B07H7VP45K 4211125662011 Beurer EMS homeSTUDIO MuskelstimulationsgerâšÂ§t, High End EMS TrainingsgerâšÂ§t1 449,99 fâšÂşr zu Hause mit App und Virtual Coach, inklusive Manschetten und Elektroden Electronics Headphones B075NXQ3BL 4010118717444 beyerdynamic Aventho wireless on-Ear-Kopfhâšâ‚rer mit Klang-Personalisierung in1 schwarz.418,98 30 Stunden Akkulaufzeit, Bluetooth kabellos, MIY App, Mikrofon Electronics Headphones B07574TYWW 714346328918 Bowers & Wilkins PX Wireless-Kopfhâšâ‚rer mit GerâšÂ§uschunterdrâšÂşckung (Noise-Cancelling),1 399,00 Space Grey Electronics Headphones B0756XMGV1 4951035065853 Bowers & Wilkins PX Wireless-Kopfhâšâ‚rer mit GerâšÂ§uschunterdrâšÂşckung (Noise-Cancelling),1 399,00 Soft Gold Personal Care Appliances Hair Removal B01MZ8DOO1 8710103779346 Philips Lumea Prestige IPL HaarentfernungsgerâšÂ§t BRI956 – Lichtbasierte1 Haarentfernung399,00 fâšÂşr dauerhaft glatte Haut - inkl.