ICT Skills Certification in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Implementation of the Communication of the European Commission on “E-Skills for the 21St Century” Or in Short "Eskills21"

EEVVAALLUUAATTIIOONN OOFF TTHHEE IIMMPPLLEEMMEENNTTAATTIIOONN OOFF TTHHEE CCOOMMMMUUNNIICCAATTIIOONN OOFF TTHHEE EEUURROOPPEEAANN CCOOMMMMIISSSSIIOONN EE--SSKKIILLLLSS FFOORR TTHHEE 2211SSTT CCEENNTTUURRYY OCTOBER 2010 Authors TOBIAS HÜSING WERNER B. KORTE Prepared for the European Commission and the European e-Skills Steering Committee empirica Gesellschaft für Kommunikations- und Technologieforschung mbH, Bonn, Germany About this document This document is the final deliverable of the study Evaluation of the Implementation of the Communication of the European Commission on “e-Skills for the 21st Century” or in short "eSkills21". Disclaimer The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the information provided in this document. About empirica GmbH empirica is an internationally active research and consulting firm concentrating on concept development, the application and development of new information and communication technology and the information society. The institute has a permanent staff from a range of disciplines, including economic, social and political sciences, IT engineering and computer science. This mix of qualifications combined with a well established network of international partners allows easy formation of interdisciplinary and international teams well tuned to study implications of the information society for citizens, businesses and governments. Contact For further information, please contact: empirica Gesellschaft für Kommunikations- und Technologieforschung mbH Oxfordstr. 2 53111 Bonn Germany Tel: (49-228) 98530-0 * e-Mail: [email protected] * Web: www.empirica.com Bonn, October 2010 2 Acknowledgements The study would not have been possible without the support of our National Correspondents in the different EU member states whose contributions are gratefully acknowledge herewith. -

User Guidelines for the Application of the European E-Competence Framework 2.0

CWA Part II User guidelines for the application of the European e-Competence Framework 2.0 These guidelines are provided to support understanding, adoption and use of the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) 2.0. The guide helps: • To explain the overall context, background and aims of the European e-Competence Framework. • To explain the main principles and methodological choices underpinning the European e-Competence Framework. • To enable ICT stakeholders – ICT user and supply companies, the public sector, ICT managers and practitioners, HR developers, ICT job seekers, educational institutions and social partners – across Europe, to adopt, apply and use the framework in their environment. A methodology document, addressing scientific and research orientated personnel, is also available. Table of contents 1. Executive overview.........................................................................................................4 1.1. Short presentation and background of the framework......................................................4 1.2. European e-Competence Framework focus and purposes ..............................................5 1.3. Main principles of the European e-Competence Framework............................................7 1.4. The user guidelines: purposes and target groups ............................................................8 2. Some Definitions.............................................................................................................9 2.1. The “e-“ from a European perspective..............................................................................9 -

UPGRADE, Vol. X, Issue No. 4, August 2009

UPGRADE is the European Journal for the Informatics Professional, published bimonthly at <http://www.upgrade-cepis.org/> Publisher UPGRADE is published on behalf of CEPIS (Council of European Pro- fessional Informatics Societies, <http://www.cepis.org/>) by Novática <http://www.ati.es/novatica/>, journal of the Spanish CEPIS society ATI Vol. X, issue No. 4, August 2009 (Asociación de Técnicos de Informática, <http://www.ati.es/>) UPGRADE monographs are also published in Spanish (full version printed; summary, abstracts and some articles online) by Novática 2 Editorial: On the 20th Anniversary of CEPIS — Niko Schlamberger UPGRADE was created in October 2000 by CEPIS and was first Monograph - 20 Years of CEPIS: Informatics in Europe published by Novática and INFORMATIK/INFORMATIQUE, bi- today and tomorrow monthly journal of SVI/FSI (Swiss Federation of Professional Informatics Societies, <http://www.svifsi.ch/>) (published jointly with Novática*) Guest Editors: Robert McLaughlin, Fiona Fanning, and Nello Scarabottolo UPGRADE is the anchor point for UPENET (UPGRADE European NETwork), the network of CEPIS member societies’ publications, that 4 Presentation: Introducing CEPIS — Robert McLaughlin, Fiona currently includes the following ones: Fanning, and Nello Scarabottolo • Informatica, journal from the Slovenian CEPIS society SDI • Informatik-Spektrum, journal published by Springer Verlag on behalf 7 A Profession for IT? — Declan Brady of the CEPIS societies GI, Germany, and SI, Switzerland 12 The European ICT Industry: Overcoming the Crisis -

User Guide for the Application of the European E-Competence Framework 3.0

User guide for the application of the European e-Competence Framework 3.0 A sharedcommon European European Framework Framework for for ICT Professionals in all industry sectors Foreword This CWA document publishes the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) version 3.0; the result of 8 years continuing effort and commitment by multi-stakeholders from the European ICT sector. The very first practical steps towards the e-CF were initiated in 2006 by Airbus, BITKOM, CIGREF, e-Skills UK, Fondazione Politecnico di Milano, IG Metall and Michelin, with the encouragement of the European Commission and strongly backed by the CEN ICT Skills Workshop community. From multiple market perspectives, roles and expertise, representatives of many organisations and also individuals have subsequently contributed to the e-CF initiative. They have collectively contributed to the development of the e-CF from their varied perspectives bringing technical expertise, political awareness or constructive feedback. The CEN ICT Skills Workshop wishes to recognize and acknowledge these multiple contributions from the following non-exhaustive list of organisations. (ISC)² Corporate IT Forum Foundation IT Leader Club MS Consulting & Research A / I / M bv CPI Competenze per Poland Ltd. AFPA l’Innovazione Fundación Inlea MTA AICA Cyprus Computer Society FZI NIOC AIP-ITCS Dassault Systèmes HBO-I Foundation Norma PME AIRBUS DEKRA Akademie GmbH HEINEKEN International Norwegian computer ASIIN e.V. Deutsche Telekom AG Hominem Challenge association Association Pasc@line Diaz Research Limited IBM UK ORACLE Associazione Informatici DND Norwegian computer ICT Human Capital PIN SME Professionisti – Italiano society IG Metall PMI computer society Dutch Ministry of Innovation Value Institute Pôle Emploi ATI Economic Affairs Innoware PROSA - Association of IT Banca d’Italia ECABO Institut PI Professionals Bayer Business Services ECDL Foundation Intel Corp. -

Paving for Efuture Meeting the Challenge of New Business Practices

The eBusiness Community Model (eBCM): May 2008 Paving for eFuture Meeting the challenge of new business practices • Which are the key elements of eBusiness? • How can a SME maneuver in a new eBusiness environment? • Why is a common focal point so important? Authors: Rúnar Már Sverrisson, Karl Henry Haglund and Guðbjörg Björnsdóttir Participants Project Partners and Contacts / National Project Team Leaders Estonia Finland Estonian Informatics Centre, EIC Finnish Information Society Development Taavi Valdlo Centre, TIEKE (Aatto Repo) Eppie Eloranta / Juhani Koivunen Iceland Romania Icelandic Standards, IST Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Rúnar Már Sverrisson Romania, CCIR Cornelia Rotaru National Key Experts Enn Õunapuu, Juhani Koivunen, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia Finnish Information Society Development Centre, Finland Arnaldur F. Axfjörð, Anemari Marcusanu, Admon ehf, Iceland Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Romania, CCIR Nordic Reference Group Denmark Estonia Peter Hersted, Taavi Valdlo, Danish Standards Estonian Informatics Centre, EIC Finland Norway Juhani Koivunen, Knut Lindelien, Finnish Information Society Development The Standardisation Organisations in Norway Centre, TIEKE Iceland Sweden Guðbjörg Björnsdóttir, Susanne Björkander, Icelandic Standards Swedish Standards Institute, SIS eBCM-RAP Services Rúnar Már Sverrisson, Karl Henry Haglund, Project Manager, External Expert, Logar ehf Haglund Networks Ltd -iii- Title: eBusiness Community Model – Research and Assessment Project, eBCM-RAP Nordic Innovation Centre project number: 04076 Author(s): Rúnar Már Sverrisson, Karl Henry Haglund and Guðbjörg Björnsdóttir Institution(s): Icelandic Standards, Logar ehf and Haglund Networks Ltd Abstract: Automated business processes offer great return on investment, more efficient business operations and enhanced competitiveness. In spite of the benefits, the cost of automation as well as the cost of employees adjusting to a new mindset is currently perceived as a threshold too big to overcome, especially for the SMEs. -

Beginnt Der Text

CEN CWA 16234-2 WORKSHOP December 2010 AGREEMENT ICS 35.020 English version European e-Competence Framework 2.0 - Part 2: User guidelines for the application of the European e-Competence Framework 2.0 This CEN Workshop Agreement has been drafted and approved by a Workshop of representatives of interested parties, the constitution of which is indicated in the foreword of this Workshop Agreement. The formal process followed by the Workshop in the development of this Workshop Agreement has been endorsed by the National Members of CEN but neither the National Members of CEN nor the CEN Management Centre can be held accountable for the technical content of this CEN Workshop Agreement or possible conflicts with standards or legislation. This CEN Workshop Agreement can in no way be held as being an official standard developed by CEN and its Members. This CEN Workshop Agreement is publicly available as a reference document from the CEN Members National Standard Bodies. CEN members are the national standards bodies of Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and United Kingdom. EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR STANDARDIZATION COMITÉ EUROPÉEN DE NORMALISATION EUROPÄISCHES KOMITEE FÜR NORMUNG Management Centre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels © 2010 CEN All rights of exploitation in any form and by any means reserved worldwide for CEN national Members. Ref. No.:CWA 16234-2:2010 D/E/F CWA 16234-2:2010 (E) Table of contents 1.Executive overview ........................................................................................................ 3 2.Some Definitions ........................................................................................................... -

E-SKILLS and ICT PROFESSIONALISM Fostering the ICT Profession in Europe

e-SKILLS AND ICT PROFESSIONALISM Fostering the ICT Profession in Europe Final Report May 2012 Research Team Stephen McLaughlin Martin Sherry Marian Carcary Conor O’Brien Fiona Fanning Dimitris Theodorakis Dudley Dolan Neil Farren Prepared for the European Commission Disclaimer The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the information provided in this document. The study team This study was conducted by: Innovation Value Institute (IVI) National University of Ireland Maynooth Ireland. Tel.: +353 1 708 6931 Fax: +353 1 708 6916 Email: [email protected] http://ivi.nuim.ie/ Stephen McLaughlin, Martin Sherry, Marian Carcary, Conor O’Brien. And Council of European Professional Informatics Societies (CEPIS) Avenue Roger Vandendriessche, 18 B-1150 Brussels Belgium. Tel: +32 2 772 1836 Fax: +32 2 646 3032 Email: [email protected] www.cepis.org Fiona Fanning, Dimitris Theodorakis, Dudley Dolan, Neil Farren. © European Commission, 2012 2 | P a g e Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 13 1.1 Context ............................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Defining the ICT professional ................................................................................................ 14 -

Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring 2008

Newsletter - Calibrated for Creative Communications Vol. 6, no. 1, Spring 2008 From the Editor Happy Spring IT STAR representatives: n early March Bulgarians greet each other with the words Austria/OCG - V. Risak, Bulgaria/BAS - K. Boyanov, I Croatia/CITS - M. Frkovic, Czech Rep./CSKI - “Happy baba Marta”, as March is often referred to, and J. Stuller, Greece/GCS - S. Katsikas, Hungary/NJSZT – exchange red and white woven strips (or small woolen B. Domolki, Italy/AICA – G. Occhini, Lithuania/LIKS - dolls named Pizho and Penda) as a token of welcome to E. Telešius, Macedonia/MASIT - P. Indovski, the incoming Spring. These decorations, worn on the Poland/PIPS – M. Holynski, Romania/ATIC – V. Baltac, lapels or around the wrist, are "Martenitsi", an authentic Serbia/JISA – D. Dukic, Slovakia/SSCS- I. Privara, Bulgarian tradition, also customary in parts of Romania, Slovenia/SSI - N. Schlamberger symbolizing conception, fertility, spring, joy, health and purity. With this regional cultural overture we unveil the March Contents: issue which covers two main topics: New Member of the Advisory Board ..............................2 • Computer History, with unique recollections on the Joke of the Issue ............................................................3 World Computer Congress .............................................3 series of world computer congresses and computer Computer History............................................................7 “firsts” IT-SKILLS.......................................................................8 -

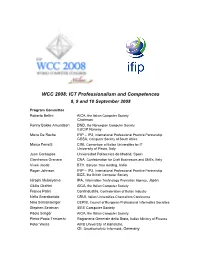

WCC 2008 – ICT Professionalism and Competences Conference Program

WCC 2008: ICT Professionalism and Competences 8, 9 and 10 September 2008 Program Committee Roberto Bellini AICA, the Italian Computer Society Chairman Renny Bakke Amundsen DND, the Norwegian Computer Society EUCIP Norway Moira De Roche IFIP – IP3, International Professional Practice Partnership CSSA, Computer Society of South Africa Marco Ferretti CINI, Consortium of Italian Universities for IT University of Pavia, Italy Juan Garbajosa Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Spain Gianfranco Granara CNA, Confederation for Craft Businesses and SMEs, Italy Vivek Jacob BTH, Banyan Tree Holding, India Roger Johnson IFIP – IP3, International Professional Practice Partnership BCS, the British Computer Society Hiroshi Mukaiyama IPA, Information-Technology Promotion Agency, Japan Giulio Occhini AICA, the Italian Computer Society Franco Patini Confindustria, Confederation of Italian Industry Nello Scarabottolo CRUI, Italian Universities Chancellors Conference Niko Schlamberger CEPIS, Council of European Professional Informatics Societies Stephen Seidman IEEE Computer Society Paolo Schgör AICA, the Italian Computer Society Pietro Paolo Trimarchi Ragioneria Generale dello Stato, Italian Ministry of Finance Peter Weiss AIFB University of Karlsruhe, GI, Gesellschaft für Informatik, Germany WCC 2008 – ICT Professionalism and Competences Conference Program Monday 8 September 2008 ICT Professional Role 09:00 ICT Professional Role in Europe Niko Schlamberger, supported by Declan Brady, Julian Seymour, Peter Weiss 09:45 The Role of Professional Societies in -

The Need for a Standard Qualification of ICT-Professional Competences

The need for a standard qualification of ICT professional competences The reasons that urged CEPIS to create the EUCIP model are even more pressing today than they were in 2000 Paolo Schgör Certifications manager at AICA, Italy, [email protected] Abstract: Standards are, generally speaking, a sensible way of simplifying a number of issues; this is also true for ICT professional competences, the standardization of which could bring huge benefits to all stakeholders, including education & training providers, employers, candidates and agencies for employment, freelance professionals, ICT associations, governmental and statistical institutions, and - finally - the ICT industry at large. The EUCIP model is certainly one of the most interesting proposals for a possible multi-stakeholder solution to this incredibly complex issue. Keywords: Europe, ICT certifications, ICT competences, professionalism, professional societies, standardization 1. The Need for Standards in ICT 1.1 Standards in a Layman's View I'm not sure whether a specific professionalism regarding the definition of standards has ever been defined (or even can be); anyway, I do not consider myself a professional “standardizer”, and the following introductory statements are offered as a layman's view. On the other hand, I have been progressively involved in international teams and task forces having an implicit – or sometimes explicit – focus on the definition of standards around ICT competences; thus, the main part of this script is dedicated to the description of the current proposals devised by CEPIS on this subject. 124 P. Schgör My thesis is that having one recognized standard may not be a vital issue, but it is much better than having several. -

The Need for a Standard Qualification of ICT Professional Competences

The need for a standard qualification of ICT professional competences The reasons that urged CEPIS to create the EUCIP model are even more pressing today than they were in 2000 Paolo Schgör Certifications manager at AICA, Italy, [email protected] Abstract: Standards are, generally speaking, a sensible way of simplifying a number of issues; this is also true for ICT professional competences, the standardization of which could bring huge benefits to all stakeholders, including education & training providers, employers, candidates and agencies for employment, freelance professionals, ICT associations, governmental and statistical institutions, and - finally - the ICT industry at large. The EUCIP model is certainly one of the most interesting proposals for a possible multi-stakeholder solution to this incredibly complex issue. Keywords: Europe, ICT certifications, ICT competences, professionalism, professional societies, standardization 1. The Need for Standards in ICT 1.1 Standards in a Layman's View I'm not sure whether a specific professionalism regarding the definition of standards has ever been defined (or even can be); anyway, I do not consider myself a professional “standardizer”, and the following introductory statements are offered as a layman's view. On the other hand, I have been progressively involved in international teams and task forces having an implicit – or sometimes explicit – focus on the definition of standards around ICT competences; thus, the main part of this script is dedicated to the description of the current proposals devised by CEPIS on this subject. Please use the following format when citing this chapter: Schgör, P., 2008, in IFIP International Federation for Information Processing, Volume 280; E-Government; ICT Professionalism and Competences; Service Science; Antonino Mazzeo, Roberto Bellini, Gianmario Motta; (Boston: Springer), pp. -

Digital Competence in Practice: an Analysis of Frameworks

Digital Competence in Practice: An Analysis of Frameworks Author: Anusca Ferrari 2012 Report EUR 25351 EN Файл загружен с http://www.ifap.ru European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Contact information Address: Edificio Expo. c/ Inca Garcilaso, 3. E‐41092 Seville (Spain) E‐mail: jrc‐ipts‐[email protected] Tel.: +34 954488318 Fax: +34 954488300 http://ipts.jrc.ec.europa.eu http://www.jrc.ec.europa.eu This publication is a Technical Report by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/. JRC68116 EUR 25351 EN ISBN 978‐92‐79‐25093‐4 (pdf) ISSN 1831‐9424 (online) doi:10.2791/82116 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 © European Union, 2012 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Spain Preface With the 2006 European Recommendation on Key Competences,1 Digital Competence has been acknowledged as one of the 8 key competences for Lifelong Learning by the European Union. Digital Competence can be broadly defined as the confident, critical and creative use of ICT to achieve goals related to work, employability, learning, leisure, inclusion and/or participation in society.