Twilight Saga As Fairy Tale and Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011)

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Film Review Aggregators and Their ffecE t on Sustained Box Officee P rformance Nicholas Krishnamurthy Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Krishnamurthy, Nicholas, "Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 291. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/291 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE FILM REVIEW AGGREGATORS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SUSTAINED BOX OFFICE PERFORMANCE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR DARREN FILSON AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY NICHOLAS KRISHNAMURTHY FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL / 2011 November 28, 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents for their constant support of my academic and career endeavors, my brother for his advice throughout college, and my friends for always helping to keep things in perspective. I would also like to thank Professor Filson for his help and support during the development and execution of this thesis. Abstract This thesis will discuss the emerging influence of film review aggregators and their effect on the changing landscape for reviews in the film industry. Specifically, this study will look at the top 150 domestic grossing films of 2010 to empirically study the effects of two specific review aggregators. A time-delayed approach to regression analysis is used to measure the influencing effects of these aggregators in the long run. Subsequently, other factors crucial to predicting film success are also analyzed in the context of sustained earnings. -

What's Right to Write?

Lemont High School 800 Porter Street Lemont, IL 60439 Tom Tom September 22, 2010 Issue 4 What’s Right to Write? by Erin O’Connor News Writer With the feel of fall in the air, high be unique and not just a list. Find- length. school seniors have a vital subject ing patterns is key, the topic is a Overall, Melei was happy with on their minds – college application zoomed out picture, but what mat- the events of the night, “Turnout essays. The process has just become ters is once you, the writer zooms was fantastic, I’m very happy…but easier as The Bridge, Lemont High in on it. I wish we could do more one on School’s writing center, recently As many students are in a one [tutoring],” following with, “I hosted its second annual “College frenzy trying to figure out what to feel the college acceptance envi- Write Night.” write, a simple visit to the writing ronment is really competitive.” On Thursday, September 16, LHS center can help them. When told College entrance essays are what seniors gathered in “The Bridge” to define talk about a community can make or break acceptance into at 6:30p.m., to get help on college service that has influenced them, a school as it has become more and essays and personal statements. many students can look at this more competitive. The student has Center director, Patty Melei, and her in utter confusion, but after last to show all they can offer through staff were on hand to generate help Thursday’s write night, Szy- so few words. -

Five Years Into Darkness

FilmBB Five years into darkness PICTURE ME: A Model’s Diary Picture Me details her (M) exhilarating rise from an This Directed by Ole Schell and 18-year-old jetting off to her first Sara Ziff shoot in Paris to receiving five- intimate ✪✪✪✪ figure cheques for a single-job. Reviewed by James Croot However, along the way, portrait this intimate portrait (Ziff even Unlike all those starry-eyed converses with the camera exposes reality-show wannabes, Sara while in the bath) exposes the the Ziff never dreamed of being a darker side of casting and top model. photo shoots and how this darker Scouted by a female industry of illusion compels its photographer while she was stars to battle exhaustion in side. walking home from school at order to pay off their debts to age 14, the New York native their agencies. It turns out all was being offered a magazine those apartments, plane tickets, shoot in Jamaica and a show food and accommodation for Calvin Klein within a week. aren’t free. Juggling school and modelling, Clever, scrapbook-style she was out-earning her credits and the near-exclusive Sara Ziff never dreamed of being a top model. university neurobiologist father use of hand-held cameras lend by the time she was 20. But as the film a homely, endearing, detailing the camaraderie McCartney, but it is her insight she details in this compelling dog-eared quality that actually between models. It isn’t long and willingness to question her and engaging documentary, gives its revelations more before the facade cracks and occupation that really enchants made with her film-school impact. -

2011 Literary Review (No. 24)

Whittier College Poet Commons Greenleaf Review Student Scholarship & Research 5-2011 2011 Literary Review (no. 24) Sigma Tau Delta Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/greenleafreview Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sigma Tau Delta, "2011 Literary Review (no. 24)" (2011). Greenleaf Review. 9. https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/greenleafreview/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship & Research at Poet Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greenleaf Review by an authorized administrator of Poet Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITERARY REVI fj An Upsilon Sigma Chapter (Sigma Tau Delta) PulLilication / 2011 Literary Review Whittier College May 2011 Number 24 An (Jp5IlOri 5ma/Jes.amjn We5t Chapter 01 5ina Tau Delta f'ub/Ica tIon 2011 Literary Review Editors: Réme Bohlin and Mary Helen Truglia Sigma Tau Delta Advisor: Dr. Sean Morris The 2011 Literary Review was designed and laid out in Microsoft Word by Mary Helen Trugila. The front cover photograph, "Contemplation at Normandy" by Catherine F. King was edited in Adobe InDesign by the brilliant Jade Wessinger of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. The back cover photograph, "Nature's Playfulness" by Garlyn Werderman was edited in Adobe InDesign by the talented Jade Wessinger of Gal Poly San Lids Obispo. The book is set in various sizes of Times New Roman and 94onotje corth.'afbnts. Printing was supervised and completed by Highlight Graphics USA Company, in Santa Fe Springs, CA. 2 Acknowledgements The editors would like to thank a number of delightful people for their participation in this labor of literary love: Professor Sean Morris: Thank you for your constant enthusiasm, advice, and for opening your home to our (incredibly long) reading party. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

Vampires Suck by Hugh Barlow

Vampires Suck by Hugh Barlow The little clapboard church sits stiffly in the sun. It's steeple marking time with it's shadow on the sidewalk. It is the last place most people would think to look for a vampire, but I am sure that one is in there. Contrary to popular opinion, there is no such thing as a noble savage. There is also no such thing as a noble vampire. I get angry when I see all the vampire based novels in the science fiction section of my favorite bookstore. “Twilight” has it all wrong. Dealing with vampires is more like the movie “The Lost Boys” than the TV show “Forever Knight.” I ain't no scientist, and I don't have a degree in biology, but I do have some practical experience in dealing with these suckers (pun intended). I discovered my first vampire quite by accident. Actually, it wasn't a human vampire, but was one of the animal variants most people don't realize are related. I have come to find out that the old stories of werewolves and were-cats are actually based on facts. Oh, the stories are twisted and exaggerated all out of proportion, but they are based on fact none the less. I had the misfortune run across one of these critters when I was out deer hunting back home, and the damned thing nearly got me. It seems that it and I were tracking the same prey, and when I shot the deer, the werewolf decided to go for me. -

Michael T. Ryan

MICHAEL T. RYAN Music Editor Credits Feature Screen Credits Year Film Director Composer 2014 Dolphin Tail 2 Charles Martin Smith Rachel Portman 2014 Superfast Aaron Seltzer & Timothy Wynn Jason Friedberg 2014 Patient Killer Casper Van Dien Chad Rehmann 2014 Lucky Stiff (music driven) Christopher Ashley Stephen Flaherty 2013 Skating To New York Charles Minsky Dave Grusin 2013 The Starving Games Aaron Seltzer & Timothy Wynn Jason Friedberg 2013 Assumed Killer Bernard Salzmann Chad Rehmann 2012 Atlas Shrugged: Part 2 John Putch Chris Bacon 2012 For Greater Glory Dean Wright James Horner 2012 High Ground Michael Brown Chris Bacon 2011 Beethoven’s Christmas Adventure * John Putch Chris Bacon 2011 Source Code Duncan Jones Chris Bacon 2010 Vampires Suck Aaron Seltzer & Christopher Lennertz Jason Friedberg 2010 The Twilight Saga Eclipse David Slade Howard Shore 2010 Love Ranch Taylor Hackford Chris Bacon 2009 Year One Harold Ramis Teddy Shapiro 2009 Bitch Slap Rick Jacobson John R. Graham 2008 Disaster Movie Aaron Seltzer & Christopher Lennertz Jason Friedberg 2008 Mirrors Alexandre Aja Javier Navarette 2008 Fools Gold Andy Tennant George Fenton 2007 What Happens In Vegas Tom Vaughan Christophe Beck 2007 Spiderman 3* Sam Raimi Chris Young 2007 Epic Movie Aaron Seltzer & Edward Shearmur Jason Friedberg 2007 Firehouse Dog Todd Holland Jeff Cardoni 2006 Click* Frank Coraci Rupert Gregson-Williams 2006 Date Movie Aaron Seltzer & David Kitay Jason Friedberg 2006 Even Money Mark Rydell Dave Grusin 2005 Fantastic Four Tim Story John Ottman 2004 Hitch Andy Tennant George Fenton 2004 Man of the House Stephen Herek David Newman 2004 Raise Your Voice* (music driven) Sean McNamera Aaron Zigman 2004 The Passion of the Christ Mel Gibson John Debney 2003 Eurotrip Jeff Schaffer, James Venable Alec Berg, Dave Mandel 2003 Grind Casey LaScala Ralph Sall 2002 The Fighting Temptations* (music driven) Jonathan Lynn Terry Lewis 2002 Sweet Home Alabama Andy Tennant George Fenton 2002 Clockstoppers Jonathan Frakes Jamshied Sharifi 5622 Irvine Ave. -

After All This Time: a Study of the Appeal of Young Adult Fiction Series Among Young Readers Sarah Jessica Martin University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 5-5-2016 After All This Time: A Study of the Appeal of Young Adult Fiction Series Among Young Readers Sarah Jessica Martin University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Sarah Jessica, "After All This Time: A Study of the Appeal of Young Adult Fiction Series Among Young Readers" (2016). Senior Theses. 75. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/75 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. After All This Time: A Study of the Appeal of Young Adult Fiction Series Among Young Readers Sarah Martin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the a degree from the South Carolina Honors College Director: Cynthia Davis Second Reader: Sara Schwebel May 2016 Table of Contents ● Introduction and Purpose of Research ● Comparative Publication and Cinematic Successes of Each Series ● Research Methodology ○ Choice of Survey and Distributor ○ Selection of Survey Participants ● Breakdown of Survey Results by Series ○ Initial Observations ○ Observation Analysis ● Commonalities and Linkages Among Series ○ Fandoms ○ Values and Lessons ○ Motivations for Reading ○ Relatability ● Study Evaluation ● Conclusions ● Appendix ○ Full Survey Results ○ Plot Summaries ● Bibliography 2 Introduction and Purpose of Research What is it about young adult fiction that is so addictive? Why do teenagers return to the same characters and situations over and over again in series fiction? This study explores the significance of young adult fiction series with a scientific approach, through the surveying of teenagers on the aspects of those series that are so meaningful to them. -

“Starcraft” Sequel Conquers Gamers' Summer

UPCOMING CAMPUS EVENTS Stupid humor in “Vampires Suck” forces sincere laughter Three, not to be missed, events coming up on campus. FEEDBACK BAR provement. gays and lesbians and top it off with a ref- The movie takes a stab at erence to Lady Gaga and there goes your If there was a the recent vampire phenom- successful box office movie recipe. Performing Arts Series enon, blending the plots of Plus, it seems like a person getting hit $5 student ticket sales. subculture based on “Twilight” and “New Moon” with a glass bottle, vase, car door, fist or When: All Semester Long When student Tony Cintrony donned your interests and with a handful of lame pop- a wall is the right way to entertain masses Where: Carlsen Center his superhero costume, he did not go culture references into one over and over again. The audience was Why You Need to Be There: To cel- trick-or-treating; he transformed into personality, th 80-minute-long movie. bursting with laughter every time. ebrate the 20 anniversary of the Batman. what would it “Vampires Suck” religious- The movie definitely exhausts all the Performing Art Series, the Carlsen Cintrony lists his reasons for dress- ly recreates and then “hu- obvious vampire jokes, therefore it is no Center is offering $5 tickets to ing as Batman to promote his new radio be called? morously” alters the original surprise when Buffy suddenly makes her students who purchase them the show. “Disco Sleaze. It’d be... week of a performance. Upcoming scenes, dialogue and charac- appearance, or that when it comes to fin- 1. -

Peripheral Phenomena: the Colliding Evolution of Darcy and Dracula

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2012-2013: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Peripheries Research Fellows 4-2013 Peripheral Phenomena: The Colliding Evolution of Darcy and Dracula Elaine Ogden University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2013 Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Ogden, Elaine, "Peripheral Phenomena: The Colliding Evolution of Darcy and Dracula" (2013). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2012-2013: Peripheries. 5. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2013/5 This paper was part of the 2012-2013 Penn Humanities Forum on Peripheries. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/peripheries. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2013/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peripheral Phenomena: The Colliding Evolution of Darcy and Dracula Abstract In this study, I examine aspects of Jane Austen, vampire fiction, and contemporary culture through the lens of vampire adaptions of Austen's work. Although a study of vampire fiction may seem peripheral to any serious study of Austen's novels, I contend that studying those adaptations is central to understanding Austen in modern culture, as her work is recycled and reapportioned. Vampire fiction's success in today's marketplace and the prevalence of modern vampire adaptions of Austen's work can reveal much about how the two disjointed parties have been united, and what it says about our culture, which so eagerly consumes them together. Disciplines Comparative Literature | English Language and Literature Comments This paper was part of the 2012-2013 Penn Humanities Forum on Peripheries. -

The Humping Games : a Parody Ebook

THE HUMPING GAMES : A PARODY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jack Gallow | 80 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781500200961 | English | none The Humping Games : A Parody PDF Book If there is a survey it only takes 5 minutes, try any survey which works for you. Jul 02, Taylor rated it liked it. Details if other :. Thank you Jack Gallow for a little break from the hum-drum of life that allowed me to prance through the fun and funnies of sex. Select a membership level. Open Preview See a Problem? Like a lot of people, I do think Friedberg and Seltzer are hacks and not one of their previous five directing-writing efforts with Disaster Movie, Epic Movie, two of the worst movies ever made , Meet the Spartans, Date Movie and Vampires Suck have been good. Jul 02, Taylor rated it liked it. Kantmiss Evershot : Like where? What is Patreon? The stakes are high and the sex is hot. So you'll just have to use your imagination for that. Today's Top Stories. Rate This. To ask other readers questions about The Humping Games , please sign up. Other editions. Why the Queen is moving out of Windsor Castle. Rudy as Eryn Davis. It was a short little book, took me less than an hour to read but it was perfect. The idea is to create fun and short games. Includes gameboard, spinner and base, cards, 4 cars, money pack, 4 savings tokens, 24 pegs, and instructions. Sharon Carter. Other Editions 1. Samia Tasnim rated it liked it Jul 04, From the manufacturer No information loaded. -

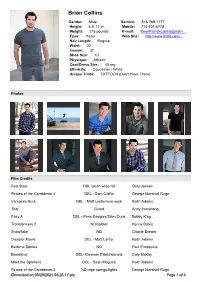

Brian Collins

Brian Collins Gender: Male Service: 818-769-1777 Height: 5 ft. 11 in. Mobile: 714-401-6778 Weight: 175 pounds E-mail: BrianPatrickCollins@hotm... Eyes: Hazel Web Site: http://www.imdb.com/... Hair Length: Regular Waist: 32 Inseam: 32 Shoe Size: 10 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 40 reg Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Unique Traits: TATTOOS (Don't Have Them) Photos Film Credits Red State DBL saran wrap fall Gary Jensen Pirates of the Carribbean 4 DBL - Sam Claflin George Marshall Ruge Vampires Suck DBL - Matt Lanter/wire work Keith Adams Thor Guard Andy Armstrong Easy A DBL - Penn Badgley/Slam Dunk Bobby King Transformers 2 ND/soldier Kenny Bates Snowflake ND Charlie Brewer Disaster Movie DBL - Matt Lanter Keith Adams Bedtime Stories ND Paul Eliopoulus Bloodshot DBL- Brennen Elliot/ratchets Cole McKay Meet the Spartans DBL - Sean Maguire Keith Adams Pirates of the Carribbean 3 ND rope swings/fights George Marshall Ruge Generated on 09/29/2021 04:28:17 pm Page 1 of 3 Con Schell Heavans Fall ND Fight/Fall Kim Koscki First Daughter ND Manny Perry Not Another Teen Movie Fight Eddie Yansick Television The Mentalist DBL - Santa - 40 ft. high fall John Brannegan CSI New York John Everett/water work Norman Howell True Blood DBL - Stephen Moyer Mike Massa Cold Cases DBL Jimmy Romano Melrose Place DBL - Glass Gag Merritt Yohnka/Brett Jones The Unit The Weekender Troy Brown How I Met Your Mother Teen Wolf - slam dunk Tim Davison Merry Christmas Drake and Josh DBL - Josh Peck Vince Deadrick Jr. Numbers DBL - Ben Corwin Peewee Piemonte E.R.