By Nick Neuman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Internet Companies and Their Quest for Globalization

International Conference on Information, Business and Education Technology (ICIBIT 2013) Chinese Internet Companies and Their Quest for Globalization Harlan D. Whatley1 1Swiss Management Center, Zurich, Switzerland Abstract players in the technology market (Sun, 2009). Chinese internet companies have seen an This qualitative research paper unprecedented growth over the past explores the quest for globalization of decade. However, very few are two successful Chinese internet recognized brands outside of China while companies: Baidu and Tencent Holdings. some seek to develop their brands in In this case study, the focus is on the foreign markets. This paper analyzes the marketing strategies of these expanding marketing strategies of two internet multinational enterprises and the companies: Baidu and Tencent and their challenges they face to become quest for globalization. recognized as global brands. All of the firms in this study were founded as Keywords: Baidu, Tencent, internet, private enterprises with no ownership ties branding, marketing, globalization, China to the Chinese government. Furthermore, an analysis of the countries and markets 1. Introduction targeted by the firms is included in the study. In addition to a review of the Innovation efforts by technology current academic literature, interviews companies in China are driven by adding were conducted with marketing and significant value to imported foreign strategy professionals from the technologies or by developing new perspective firms as well as journalists products to satisfy specific domestic that closely follow Chinese internet firms demands (Li, Chen & Shapiro, 2010). and the technology sector. This study on Firms in the emerging market of China do the globalization of Chinese internet not possess the R&D resources that their firms will contribute to marketing developed Western counterparts have. -

Complaint for Patent Infringement

Case 1:16-cv-00122-LPS Document 1 Filed 03/02/16 Page 1 of 17 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES ) CORPORATION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) C.A. No. ________________ ) v. ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ) GROUPON, INC. ) ) Defendant. ) COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff International Business Machines Corporation (“IBM”), for its Complaint for Patent Infringement against Groupon, Inc. (“Groupon”) alleges as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. IBM is a world leader in technology and innovation. IBM spends billions of dollars each year on research and development, and those efforts have resulted in the issuance of more than 60,000 patents worldwide. Patents enjoy the same fundamental protections as real property. IBM, like any property owner, is entitled to insist that others respect its property and to demand payment from those who take it for their own use. Groupon has built its business model on the use of IBM’s patents. Moreover, despite IBM’s repeated attempts to negotiate, Groupon refuses to take a license, but continues to use IBM’s property. This lawsuit seeks to stop Groupon from continuing to use IBM’s intellectual property without authorization. NATURE OF THE CASE 2. This action arises under 35 U.S.C. § 271 for Groupon’s infringement of IBM’s United States Patent Nos. 5,796,967 (the “’967 patent”), 7,072,849 (the “’849 patent”), 5,961,601 (the “’601 patent”), and 7,631,346 (the “’346 patent”) (collectively the “Patents-In- Suit”). Case 1:16-cv-00122-LPS Document 1 Filed 03/02/16 Page 2 of 17 PageID #: 2 THE PARTIES 3. -

Apple , Amazon, Facebook,Generalelectric, Google, Groupon

Apple , Amazon, Facebook,GeneralElectric, Google, Groupon, Intel,Microsoft,Twitter Zynga……………….. Brand element choice mix Roles that brands play Consumers Identification of source of product Assignmentof responsibility to product maker Risk reducer Search cost reducer Promise, bond, or pact with maker of product Signalof quality Roles that brands play Manufacturers Means of identification to simplify handling or tracing Meansof legally protecting unique features Signalof quality level to satisfiedcustomers Means of endowing products with unique associations Sourceof competitiveadvantage Source of financial returns Functionalrisk: The product does not perform up to expectations. Physical risk: The product poses a threat to the physical well-being or health of the user or others. Financial risk: The product is not worth the price paid. Social risk: The product results in embarrassment from others. Time risk: The failure of the product results in an opportunity cost of finding another satisfactory product. Psychological risk: The product affects the mental well-being of the user. Founded in 1998 by two Stanford University Ph.D. students, Google takes its name from a play on the word googol—the number 1 followed by 100 zeroes— a reference to the huge amount of data online. Google’sstated mission is “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” The company has become the market leader in the search engine industry through its business focus and constant innovation. Its home page focuses on searches but also allows users to employ many other Google services. By focusing on plain text, avoiding pop-up ads, and using sophisticated search algorithms, Googleprovides fast and reliable service. -

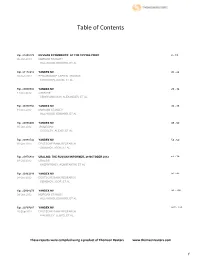

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Rpt. 21255179 RUSSIAN ECOMMERCE: AT THE TIPPING POINT 2 - 19 06-Jan-2013 MORGAN STANLEY - HILL-WOOD, EDWARD, ET AL Rpt. 21172912 YANDEX NV 20 - 24 10-Dec-2012 RENAISSANCE CAPITAL (RUSSIA) - FERGUSON, DAVID, ET AL Rpt. 20990586 YANDEX NV 25 - 34 31-Oct-2012 OTKRITIE - VENGRANOVICH, ALEXANDER, ET AL Rpt. 20990750 YANDEX NV 35 - 48 31-Oct-2012 MORGAN STANLEY - HILL-WOOD, EDWARD, ET AL Rpt. 20986606 YANDEX NV 49 - 52 30-Oct-2012 JPMORGAN - GOGOLEV, ALEXEI, ET AL Rpt. 20988742 YANDEX NV 53 - 62 30-Oct-2012 DEUTSCHE BANK RESEARCH - SEMENOV, IGOR, ET AL Rpt. 20976882 URALSIB: THE RUSSIAN INFORMER, 29 OCTOBER 2012 63 - 79 29-Oct-2012 URALSIB - CHERNYSHEV, KONSTANTIN, ET AL Rpt. 20943399 YANDEX NV 80 - 92 24-Oct-2012 DEUTSCHE BANK RESEARCH - SEMENOV, IGOR, ET AL Rpt. 20864279 YANDEX NV 93 - 106 09-Oct-2012 MORGAN STANLEY - HILL-WOOD, EDWARD, ET AL Rpt. 20797687 YANDEX NV 107 - 125 20-Sep-2012 DEUTSCHE BANK RESEARCH - WALMSLEY, LLOYD, ET AL These reports were compiled using a product of Thomson Reuters www.thomsonreuters.com 1 MORGAN STANLEY RESEARCH EUROPE Happy 5th Birthday, Risk-Reward Morgan Stanley & Co. International Edward Hill-Wood plc+ Triangle! And it works. [email protected] +44 (0)20 7425 9224 Find out why... Morgan Stanley & Co. International Nicholas J Ashworth, CFA plc+ [email protected] +44 (0)20 7425 7770 Morgan Stanley & Co. International Maryia Berasneva January 6, 2013 plc+ [email protected] +44 (0)20 7425 7502 Morgan Stanley & Co. International Liz A Rich Industry View Russian eCommerce plc+ In-Line OOO Morgan Stanley Bank+ Polina Ugryumova, CFA At the Tipping Point We forecast the Russian eCommerce sector to grow Russian eCommerce: 44% CAGR 2012-14e 35% pa to 2015, reaching 4.5% of retail sales. -

View/Download This Product's Brochure (PDF)

Social, Mobility, Analytics and Cloud (SMAC): Market Opportunity Analysis and Forecasts 2015 - 2020 Product ID R-1504SMA | Research Report: 75 pages, published April 2015 o Single user license $1,995 o Team license $2,995 o Companywide license $4,995 Related Courses and Curricula Courses: Telecom for non-engineers Courses: Cloud Computing Report in a Nutshell The convergence of social media, mobile, analytics, and cloud (SMAC) is one of the most impactful trends for both consumer and enterprise realization within digital media, communications, applications, content, and commerce. Instead of implementing solutions separately SMAC encourages an organization to build and deploy integrated solutions wherein social/mobile adds connectedness and cloud/analytics make the organization more agile and responsive. This convergence also increases innovation to create new products, services, and customers. We predict that SMAC convergence will continue shaping the future enterprise, making them ready to adopt more end-to-end technology solutions. SMAC has changed the traditional work pattern of organization enabling internal and external customers to interact with enterprise and to become more informed decision maker. The SMAC solution market is predicted to generate considerable revenue through 2020 holding 80% of total enterprise IT investment. Individually, mobile related applications are going to contribute highest percentage of SMAC market. By way of example, IBM invested $4 billion last year and is expecting $40 billion in annual revenue by 2018. This research evaluates SMAC market from a 360 degree perspective such as overview of SMAC technology, its impact on both market and enterprise, the SMAC induced structure of post-digital Website: www.eogogics.com or www.gogics.com Tel. -

Is Groupon (GRPN) Worth the $13.24 Billion the Market Is Currently Valuing It At?

Is Groupon (GRPN) worth the $13.24 billion the market is currently valuing it at? On November 4th, 2011 Groupon raised $700 million in the largest IPO for a U.S. Internet-related firm since Google raised $1.66 billion in August 2004. Groupon finished the day up nearly 31% valuing the local e-commerce discount marketplace at $16.65 billion – more than Nordstrom ($10.7 billion) and The Hershey Company (13.91 billion). Today, many investors remain skeptical of Groupon’s valuation discounting its strategy for a glorified email directory and others believe Groupon is the market leader in a distributive technology that has been opportunistic in capturing a massive e-commerce market. We look forward to a collaborative discussion on the valuation of Groupon - Monday, February 30th at 7pm in N100 BCC! We have attached a few articles that we have selected to give us some common ground to become familiar with Groupon and differing perspectives on its valuation. This is simply a starting point we encourage everyone to research at least one additional source to add to the potential depth of our discussion. For those who are really motivated and ambitious the S-1 filing and prospectus are a great source of information as well! Articles: - “Groupon Therapy” (Vanity Fair, Lauren Etter) - “Groupon Gropes for Growth” (Barron’s, Andrew Bary) - “I Wouldn’t Touch Groupon’s Stock At The IPO Price With A 50-Foot Pole” (Business Insider, Henry Blodget) - “How to justify Groupon’s Valuation” (Reuters Opinion, Felix Salmon) Valuation Tool - Trefis (GRPN) Interview (Optional, But Insightful!) - “The Death-Stare Stylings of Groupon’s Andrew Mason: The Full D9 Interview (Video)” (All Things D, Kara Swisher) . -

Amazon Invests $175M in Groupon Competitor 3 December 2010, by RACHEL METZ , AP Technology Writer

Amazon invests $175M in Groupon competitor 3 December 2010, By RACHEL METZ , AP Technology Writer (AP) -- Amazon.com Inc. said Thursday that it was founded in 2007 and initially offered the social invested $175 million in social coupon service discovery Facebook app "Visual Bookshelf" and LivingSocial - the latest sign that the online retailer later another one called "PickYourFive." The is delving into promising new methods of e- company began rolling out daily deals in July 2009. commerce. So far, that more recent business venture seems to Similar to popular online coupon site Groupon, be working. Spokeswoman Korina Buhler said LivingSocial lets users sign up for daily discounts LivingSocial is booking, on average, more than $1 that are generally for 50 to 70 percent off at local million in revenue each day from its daily deals, and businesses like pizzerias and hair salons. If you expects to earn more than $100 million this year. refer three friends who end up buying the same The company is on track to book more than $500 deal, you get the deal for free. million in revenue from deals in 2011, she said. The investment comes as published reports say Amazon shares rose 47 cents to $177 in after- Google Inc. may be close to buying Groupon, hours trading. The stock had finished regular which launched in late 2008 and kickstarted the trading down 2 cents at $176.53. market for group discounts online, in a deal worth as much as $6 billion. Such a deal would be ©2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. -

DECK TEMPLATE V1.0

INVESTOR PRESENTATION May 2019 NASDAQ: GRPN / [email protected] Forward-Looking Statements The statements contained in this release that refer to plans and expectations for the next quarter, the full year or the future are forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, including statements regarding our future results of operations and financial position, business strategy and plans and our objectives for future operations. The words "may," will," should," "could," "expect," anticipate," "believe,“ "estimate," intend," "continue" and other similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. We have based these forward looking statements largely on current expectations and projections about future events and financial trends that we believe may affect our financial condition, results of operations, business strategy, short-term and long-term business operations and objectives, and financial needs. These forward-looking statements involve risks and uncertainties that could cause our actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied in our forward-looking statements. Such risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to, risk related to volatility in our operating results; execution of our business and marketing strategies; retaining existing customers and adding new customers; challenges arising from our international operations, including fluctuations in currency exchange -

Groupon Expands Merchant Platform, Providing Local Businesses Everything They Need to Create and Manage a Successful Promotion

March 15, 2016 Groupon Expands Merchant Platform, Providing Local Businesses Everything They Need to Create and Manage a Successful Promotion Updates include revamped mobile and web merchant tools, a new tablet app to easily track and manage Groupon campaigns and a more robust self-service platform CHICAGO--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Today, Groupon (NASDAQ: GRPN) (http://www.groupon.com) announced a series of website, mobile and tablet enhancements that make it easier for merchants to create and manage the perfect Groupon marketing campaign for their business across any of their devices, wherever they're located. The updates include: redesigned web and mobile tools--all under the Groupon Merchant™ brand (http://www.groupon.com/merchant), a new tablet app that allows users to track and manage their Groupon campaign and more self-service deal options, providing merchants the ability to customize the structure and appearance of their promotion. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160315006141/en/ "We've seen first hand that local businesses can compete in an increasingly connected world and against online giants, and we're focused on continuing to enable that competition," said Aaron Cooper, SVP of North America Services, Groupon. "There is no one-size-fits-all approach to bringing in new customers, which is why we're giving merchants every option they need to run a promotion with us in a way that's the most advantageous for their business." Revamped Mobile and Web Tools Enhanced browsing, mobile responsive interface and information about Groupon solutions sorted by merchant categories The new Groupon Merchant tablet app works in tandem with existing web and and business goals to make it easier for mobile tools so merchants can track and manage their Groupon campaigns across local businesses to find the information they all of their devices. -

Collective Attention and the Dynamics of Group Deals

WWW 2012 – MSND'12 Workshop April 16–20, 2012, Lyon, France Collective Attention and the Dynamics of Group Deals ∗ Mao Ye Thomas Sandholm Chunyan Wang Social Computing Group Social Computing Group Dept. of Applied Physics HP Labs HP Labs Stanford University California, USA California, USA California, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Christina Aperjis Bernardo A. Huberman Social Computing Group Social Computing Group HP Labs HP Labs California, USA California, USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION We present a study of the group purchasing behavior of daily Attracting the attention of potential customers in today’s deals in Groupon and LivingSocial and formulate a predic- information rich social media is a challenge. As a result mar- tive dynamic model of collective attention for group buying keters have been forced to target customers in more sophis- behavior. Using large data sets from both Groupon and ticated ways. Location-based (regional) and hyper-location- LivingSocial we show how the model is able to predict the based (within eye-sight) targeting has turned out to be very success of group deals as a function of time. We find that effective in terms of improving conversion rates from views to Groupon deals are easier to predict accurately earlier in the purchases [11]. However, since people are unwilling to share deal lifecycle than LivingSocial deals due to the total number their exact locations out of privacy concerns they need to be of deal purchases saturating quicker. One possible explana- given some incentive to reveal their position. -

Introducing the 2010 Venture Capital

LivingSocial To Overtake Groupon With $400M: LivingSocial Investor by Tomio Gerom UPDATED: Daily deals website LivingSocial has “Groupon is more downmarket, more coupons, closed on $400 million in new venture as opposed to LivingSocial is a more affluent, financing at close to a $3 billion valuation. aspirational, lifestyle thing,” Chaffee said. “In terms of marketing positions I think you’ll see But will it also soon overtake Groupon as the LivingSocial emerge as more an affluent brand– leader in the space? not super high end but in relative positioning.” LivingSocial has been gaining market share from The rivalry between LivingSocial and Groupon Groupon over the last six months and will will be interesting to watch. Groupon has eventually overtake Groupon, said Todd recently raised more than $1 billion in new Chaffee, general partner at new LivingSocial financing and is still the giant to beat in the investor Institutional Venture Partners. space. However, this is not necessarily a “Our investment thesis is not necessarily that it winner-take-all market, Chaffee said. will surpass Groupon but my instincts are that it LivingSocial confirmed the new $400 million will,” Chaffee said. “(LivingSocial) will make a funding that was earlier reported by the New very nice return if it’s always ‘number 2′ but I York Times. The investment was provided by think it will surpass Groupon.” new investors including T. Rowe Price and Why does Chaffee think that? Institutional Venture Partners and existing investors Lightspeed Ventures Partners and Because LivingSocial is going after a more Amazon.com. affluent lifestyle-oriented target market, whereas Groupon is going for more of a land Meanwhile, LivingSocial has 26 million grab, he said. -

Market Models for Federated Clouds Ioan Petri, Javier Diaz-Montes, Mengsong Zou, Tom Beach, Omer Rana and Manish Parashar

This article has been accepted for publication in a future issue of this journal, but has not been fully edited. Content may change prior to final publication. Citation information: DOI 10.1109/TCC.2015.2415792, IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 1 Market models for federated clouds Ioan Petri, Javier Diaz-Montes, Mengsong Zou, Tom Beach, Omer Rana and Manish Parashar Abstract—Multi-cloud systems have enabled resource and service providers to co-exist in a market where the relationship between clients and services depends on the nature of an application and can be subject to a variety of different Quality of Service (QoS) constraints. Deciding whether a cloud provider should host (or finds it profitable to host) a service in the long-term would be influenced by parameters such as the service price, the QoS guarantees required by customers, the deployment cost (taking into account both cost of resource provisioning and operational expenditure, e.g. energy costs) and the constraints over which these guarantees should be met. In a federated cloud system users can combine specialist capabilities offered by a limited number of providers, at particular cost bands – such as availability of specialist co-processors and software libraries. In addition, federation also enables applications to be scaled on-demand and restricts lock in to the capabilities of a particular provider. We devise a market model to support federated clouds and investigate its efficiency in two real application scenarios:(i) energy optimisation in built environments and (ii) cancer image processing both requiring significant computational resources to execute simulations. We describe and evaluate the establishment of such an application based federation and identify a cost-decision based mechanism to determine when tasks should be outsourced to external sites in the federation.