Soccer's Concussion Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

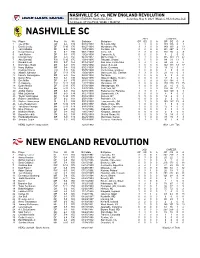

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Ucla World Cup Players 2006

UCLA’S NATIONAL TEAM CONNECTION Snitko competed for the United States in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team UCLA WORLD CUP PLAYERS 2006 ........Carlos Bocanegra included six former Bruins ̶ Friedel, ........................Jimmy Conrad Henderson, Jones, Lapper, Moore and ............................ Eddie Lewis Zak Ibsen ̶ on its roster, the most .............Frankie Hejduk (inj.) from any collegiate institution. Other 2002 ..................Brad Friedel UCLA Olympians include Caligiuri, ...................... Frankie Hejduk .............................. Cobi Jones Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................ Eddie Lewis Hooker (1984). ......................Joe-Max Moore Several Bruins were instrumental to 1998 ..................Brad Friedel ...................... Frankie Hejduk the United States’ gold medal win .............................. Cobi Jones at the 1991 Pan American Games. ......................Joe-Max Moore Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while 1994 ................Paul Caligiuri Moore nailed the game-winning goal ............................Brad Friedel in overtime in the gold-medal match .............................. Cobi Jones against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Mike Lapper ......................Joe-Max Moore Bruins Pete Vagenas, Ryan Futagaki, Carlos Bocanegra, Sasha and an assist against Canada. A Bruin- Victorine and Steve Shak (clockwise from top left) won bronze 1990 ................Paul Caligiuri dominated U.S. team won a bronze medals for the U.S. at the 1999 Pan -

Sponsorship Kit

Western Mass Pioneers Sponsorship Kit Western Mass Pioneers PO Box 457 Ludlow, MA 01056 Tel: (413) 583-4814 Fax: (413) 547-6225 [email protected] Commitment to Our Sponsors Our commitment to valued sponsors like yourself, is to continue to seek and present multiple marketing mediums in which you may present your business products and/or services. Thousands of Western Mass Pioneers fans gather in Lusitano Stadium more than once a week. Studies show that a brand needs to be flashed before clients a minimum of 5-7 times before a client actually recognizes the brand and starts paying attention! Make thousands of prospects within your target audience recognize your brand multiple times every week and grow your business! Since 1997, the Western Mass Pioneers have played their hearts out in Lusitano Stadium. In over 13 years, we’ve developed our team into perennial contenders, along with a Junior program and sprouting campaigns, such as soccer camps. Our goal is to share the love of the game with everyone we meet, and to build a passion for the sport we have dedicated our lives to. Thank you for being a supporter of our team. For each game we play, we are building a legacy. We aim to contend for the championship each year, and hope you will continue to be there to cheer us on. We sincerely appreciate your support, The Western Mass Pioneers Family Whoho we are WHO ARE THE WESTERN MASS PIONEERS? The Western Mass Pioneers Soccer Club was founded in 1997 and entered into USL D-3 league action for the 1998 season. -

2011 Nerevolution Mg Sm.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLUB PAGE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM PAGE Welcome 2 Program Overview 198 2011 Schedule 4 Youth Program Date of Note 198 2011 Quick Facts 5 U.S. Soccer Development Academy 199 Club History 6 SUM Under-17 Cup 199 THE CLUB Gillette Stadium 8 U.S. Soccer Development Academy Clubs 200 Investor/Operators 10 Coaching Staff 201 Executives 12 Academy Alumni 202 Team Staff 14 2011 Schedules 203 Uniform History 17 Under-18 Squad 204 Under-16 Squad 206 2011 REVOLUTION PAGE 2011 Alphabetical Roster 20 MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER PAGE 2011 Numerical Roster 20 MLS Staff Directory 210 2011 Team TV/Radio Guide 21 MLS Player Rules and Regulations 211 How the Revolution Was Built 22 2010 In Review 215 Head Coach Steve Nicol 23 Chicago Fire 216 Assistant Coaches 24 Chivas USA 218 Team Staff 25 Colorado Rapids 220 Player Profiles 28 Columbus Crew 222 D.C. United 224 TEAM HISTORY PAGE FC Dallas 226 Year-by-Year Results 64 Houston Dynamo 228 2010 In Review 65 LA Galaxy 230 2009 In Review 70 New York Red Bulls 232 2008 In Review 76 Philadelphia Union 234 2007 In Review 82 Real Salt Lake 236 2006 In Review 88 San Jose Earthquakes 238 2005 In Review 94 Seattle Sounders FC 240 2004 In Review 100 Sporting Kansas City 242 2003 In Review 106 Toronto FC 244 2002 In Review 112 Portland Timbers 246 2001 In Review 119 Vancouver Whitecaps 246 2000 In Review 124 2011 Conference Alignments 247 1999 In Review 130 1998 In Review 135 MEDIA INFORMATION PAGE 1997 In Review 140 General Information & Policies 250 1996 In Review 146 Revolution Communications Directory -

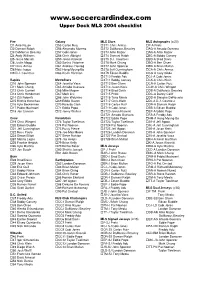

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2004

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2004 checklist Fire Galaxy MLS Stars MLS Autographs (x/20) 1 Ante Razov 55 Carlos Ruiz ST1 Chris Armas P-A Preki 2 Damani Ralph 56 Alejandro Moreno ST2 DaMarcus Beasley AG-A Amado Guevara 3 DaMarcus Beasley 57 Cobi Jones ST3 Ante Razov AR-A Ante Razov 4 Andy Williams 58 Chris Albright ST4 Damani Ralph BC-A Bobby Convey 5 Jesse Marsch 59 Jovan Kirovski ST5 D.J. Countess BD-A Brad Davis 6 Justin Mapp 60 Sasha Victorine ST6 Mark Chung BO-A Ben Olsen 7 Chris Armas 61 Andreas Herzog ST7 John Spencer BR-A Brian Mullan 8 Nate Jaqua 62 Hong Myung-Bo ST8 Jeff Cunningham CA-A Chris Armas 9 D.J. Countess 63 Kevin Hartman ST9 Edson Buddle CG-A Cory Gibbs ST10 Freddy Adu CJ-A Cobi Jones Rapids MetroStars ST11 Bobby Convey CK-A Chris Klein 10 John Spencer 64 Joselito Vaca ST12 Ben Olsen CR-A Carlos Ruiz 11 Mark Chung 65 Amado Guevara ST13 Jason Kreis CW-A Chris Wingert 12 Chris Carrieri 66 Mike Magee ST14 Brad Davis DB-A DaMarcus Beasley 13 Chris Henderson 67 Mark Lisi ST15 Preki DC-A Danny Califf 14 Zizi Roberts 68 John Wolyniec ST16 Tony Meola DD-A Dwayne DeRosario 15 Ritchie Kotschau 69 Eddie Gaven ST17 Chris Klein DJ-A D.J. Countess 16 Kyle Beckerman 70 Ricardo Clark ST18 Carlos Ruiz DR-A Damani Ralph 17 Pablo Mastroeni 71 Eddie Pope ST19 Cobi Jones EB-A Edson Buddle 18 Joe Cannon 72 Jonny Walker ST20 Jovan Kirovski EP-A Eddie Pope ST21 Amado Guevara FA-A Freddy Adu Crew Revolution ST22 Eddie Pope HM-A Hong Myung-Bo 19 Chris Wingert 73 Taylor Twellman ST23 Taylor Twellman JA-A Jeff Agoos 20 Edson Buddle 74 -

NCAA Tournament Results

Radio/TV Roster 00 Pepe Barroso Silva 1 Juan Cervantes 2 Javan Torre 3 Michael Amick 4 Grady Howe 5 Chase Gasper GK • 6-2/170 • RS Fr. GK • 5-11/180 • RS Jr. D • 6-2/175 • Sr. D • 6-0/170 • Jr. MF/D • 5-10/175 • Sr. D • 6-0/180 • So. 6 Jordan Vale 7 Felix Vobejda 8 Willie Raygoza 9 Abu Danladi 10 Brian Iloski 11 Larry Ndjock MF • 5-11/170 • Sr. MF • 5-8/155 • Jr. MF • 5-8/150 • Jr. F • 5-10/170 • So. MF • 5-7/150 • Jr. F • 5-9/175 • Sr. 12 Gage Zerboni 13 Nico Gonzalez 14 William Cline 15 Jackson Yueill 16 Christian Chavez 17 Seyi Adekoya F/MF • 5-10/160 • Jr. MF • 5-9/150 • RS Jr. MF • 5-10/165 • So. MF • 5-10/165 • Fr. F • 5-11/170 • So. F • 5-11/170 • So. 18 Jose Hernandez 19 Blayne Martinez 20 Erik Holt 21 Kingsley Firth 22 Stephen Payne 24 Nathan Smith MF • 5-6/140 • Fr. F • 6-1/175 • Fr. D • 6-1/185 • Fr. F/MF • 6-0/180 • Fr. F/MF • 5-10/155 • Fr. D • 5-10/165 • Jr. 25 Joab Santoyo 26 Tobi Henneke 27 Abdullah Adam 28 Matthew Powell 29 DJ Villegas 30 Edgar Contreras MF • 5-10/165 • RS Fr. MF • 5-8/155 • Fr. F • 6-1/175 • Jr. MF • 6-1/175 • Fr. F • 5-6/145 • Fr. D • 6-0/185 • RS Sr. 32 Dakota Havlick 33 Cole Martinez 34 Robert Knights 99 Malcolm Jones GK • 6-1/170 • Fr. -

All-Time Numerical Roster (Since 1981)

All-Time Numerical Roster (since 1981) #00 John O’Brien (92-93) #12 Nick Skvarna (86-87-88) Reid Hukari (10-11) Kevin Weiner (07-08-09-10) Justin Selander (94-95) Jose Guzman (81) Pat McLaughlin (89) Munny Manak (12-13) Jake Tenzer (11) Damon Bradshaw (96) Doug Swanson (82-83-84-85) Zak Ibsen (90-91-92) #23 Pepe Barroso Silva (14) Carlos Bocanegra (97-98-99) Ray Fernandez (86) Ante Razov (93-94-95) Joe D’Annunzio (82) #0 Nelson Akwari (00) Fabrizio Luppi (87) Nick Paneno (96) Arimin Munevar (88) Eric Conner (05) Cliff McKinley (01-02-03) Sam George (88-89-90-91) Jimmy Conrad (97) Matt Arnett (89) Alex Padilla (13) Ramon Manak (04-05) Phillip Martin (92-93-94-95) Craig Hart (98) Isaac Adamson (90) Sean Alvarado (06-07-08-09) Seth George (96) Scot Thompson (99-00-01-02) Joe Christie (93) #1 Matt Wiet (10-11-12) Sasha Victorine (97-98-99) Kiel McClung (03-04-05-06) John Glenn (81) Drew Gardner (94) Jordan Vale (13) Leonard Griffi n (00-01-02-03) Andrew Sinderhoff (07-08-09) Tim Harris (81-82-83) Kevin Shepela (95) Grady Howe (14) Damon James (04-05-06) Chandler Hoffman (10-11) David Vanole (81-82-84-85) Craig Hart (96) Tomer Konowiecki (07) Nati Schnitman (12-13) Drew Leonard (83-84-85) #7 Martin Bruno (97) Cesar Morales (09) Seyi Adekoya (14) Ed Austin (84) Tibor Pelle (81) McKinley Tennyson Jr. (98) Ryan Hollingshead (10-11-12) Anton Nistl (86-87-88-89) Mike Arya (82-83) #18 Joe Woznuk (99) Gage Zerboni (13-14) Nat Gonzalez (88-89-90-91) Shaun Del Grande (84-86-87) David Brennan (81) Tony Lawson (00-01-02-03) Robert Silverman (88) Chris Roosen (85) #13 Keith Sutton (82) Trini Gomez (04) Brad Friedel (90-91-92) Tim Gallegos (88-89-90-91) Mark Clay (81-82-84-85) Afshin Ghotbi (83) Mike Gardner (05) Chris Snitko (92-93-94-95) Philip Button (92-93) Scott Barbour (83) Pieter Lehrer (84-85) Patrick Rickards (06-07) Kevin Shepela (92-93-94) Kenny Wright (94-95) Will Steadman (86) Lucas Martin (86-87-88) Luis Serrano (08-09) Matt Reis (94-97) Pete Vagenas (96-97-98-99) Brad McAdams (87) Tayt Ianni (90) Michael Roman (10) Kevin Hartman (94-96) Ty Maurin (00-01-02-03) J.B. -

200-242 MLS.Pdf

mls staff directory 420 Fifth Avenue, 7th Floor New York, New York 10018 Phone (212) 450-1200 Fax (212) 450-1300 www.MLSnet.com DON GARBER MLS Commissioner COMMISSIONER'S OFFICE LEGAL Commissioner Don Garber VP Business and Legal Affairs William Z. Ordower President, MLS Mark Abbott Legal Counsel Jennifer Duberstein President, SUM Doug Quinn Associate Legal Counsel Brett Lashbrook Executive VP MLS JoAnn Neale Administrator, Legal Jasmin Rivera Chief Financial Officer Sean Prendergast Sr. VP of Strategic Business Development Nelson Rodriguez BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Special Assistant to the Commissioner Ali Curtis Exec. Vice President, SUM Kathryn Carter Executive Assistant to the Commissioner Erin Grady VP, Business Development Michael Gandler Executive Assistant to Mark Abbott Ashley Drezner Director, Online Ad Network Chris Schlosser Manager, Business Development Courtney Carter BROADCASTING Manager, Business Development Steve Jolley Executive Producer, Broadcasting/SUM Michael Cohen Manager, Business Development Anthony Rivera Director, Broadcasting Larry Tiscornia Executive Assistant, SUM Monique Beau Manager, Broadcasting Jason Saghini Executive Assistant, SUM Alyssa Enverga Coordinator, Broadcasting Johanna Rojas Consultant, SUM Dave Mosca Consultant, Digital Strategy Ahmed El-Kadars COMMUNICATIONS AND MLS INTERNET NETWORK Sr. VP, Marketing and Communications Dan Courtemanche PARTNERSHIP MARKETING Director, Communications Will Kuhns Vice President, Partnership Marketing David Wright Director, International Communications Marisabel Munoz -

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2005

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2005 checklist Fire Revolution MLS Goal Men MLSignatures (x/25) 1 Tony Sanneh 59 Pat Noonan GM1 Justin Mapp AE-S Alecko Eskandarian 2 Ante Razov (Crew) 60 Taylor Twellman GM2 Joe Cannon AG-S Amado Guevara 3 Andy Herron 61 Steve Ralston GM3 Edson Buddle AR-S Ante Razov 4 Chris Armas 62 Andy Dorman GM4 Jon Busch BC-S Brian Ching 5 Kelly Gray 63 Jose Cancela GM5 Eddie Johnson BM-S Brian Mullan 6 Nate Jaqua 64 Clint Dempsey GM6 Freddy Adu CA-S Chris Armas 7 Justin Mapp 65 Matt Reis GM7 Jaime Moreno CD-S Clint Dempsey 66 Jay Heaps GM8 Josh Wolff CJ-S Cobi Jones Rapids GM9 Nick Rimando CR-S Carlos Ruiz 8 Joe Cannon Earthquakes GM10 Davy Arnaud DA-S Davy Arnaud 9 Pablo Mastroeni 67 Craig Waibel GM11 Carlos Ruiz DK-S Dema Kovalenko 10 Landon Donovan (Galaxy) 68 Ryan Cochrane GM12 Amado Guevara EB-S Edson Buddle 11 Jean Philippe Peguero 69 Pat Onstad GM13 Pat Noonan EG-S Eddie Gaven 12 Mark Chung 70 Brian Ching GM14 Taylor Twellman EP-S Eddie Pope 13 Jordan Cila 71 Brian Mullan GM15 Pat Onstad FA-S Freddy Adu 14 Chris Henderson 72 Dwayne De Rosario GM16 Brian Ching JA-S Jonny Walker 73 Troy Dayak GM17 Ante Razov JB-S Jon Busch Crew 74 Eddie Robinson GM18 Jeff Cunningham JC-S Joe Cannon 15 Edson Buddle JG-S Jeff Agoos 16 Jon Busch CD Chivas USA MLS Jersey JK-S Jason Kreis 17 Jeff Cunningham (Rapids) 75 Arturo Torres BC-J Brian Ching JM-S Justin Mapp 18 Ross Paule 76 Orlando Perez CA-J Chris Armas JO-S Jaime Moreno 19 Klye Martino 77 Ezra Hendrickson CR-J Carlos Ruiz JP-S Jean Philippe Peguero 20 Simon Elliott -

Sounders-Chivas 0813

Seattle Sounders FC vs. LA Galaxy Where: CenturyLink Field When: Saturday, 1 p.m. TV/Radio: KING (5)/KIRO (97.3 FM) Records: Sounders (11-5-8, 41 pts); Chivas USA (7-8-8 29 pts) Standings/Power poll: SEA (3W/1st Tier); CHV (6W/3rd Tier) SSFC formation: 4-4-2 CHV formation: 4-4-2 18!RW 15!LM 13!D 12!LB Blair Alvaro Ante Leo Gavin Fernandez Jazic Gonzalez 34!CB 17!F 24!F 3!D Jhon K. Justin Roger Heath Hurtado Braun Levesque Pearce 18!GK 6!CM 8!CM 10!CM 9!CM 1!GK Kasey Osvaldo Erik Nick Simon Dan Keller Alonso Friberg LaBrocca Elliott Kennedy ! 31!CB 15!F 17!F 4 D Jeff Alejandro Fredy Michael Parke Moreno Montero Umana 10!RM 19!LW 7!RB Mauro 20!D James Jorge Rosales Zarek Riley Flores Valentin Referee: Kevin Stott Name Pos No. GA Sh Min SV% GAA Name Pos No. GA Sh Min SV% GAA Kasey Keller G 18 27 93 2160 0.710 1.13 Dan Kennedy G 1 22 93 1890 0.763 1.05 Josh Ford G 29 0 0 0 0.00 0 Zach Thornton G 22 4 7 180 0.429 2.00 Name Pos No. G A Min PP90 Sht Name Pos No. G A Min PP90 Sht Projected starters Projected Mike Fucito F 2 0 1 530 0.17 16 Andrew Boyens D 2 1 0 610 0.30 4 Patrick Ianni D 4 1 0 1007 0.18 5 Heath Pearce D 3 0 2 2070 0.09 9 Tyson Wahl D 5 1 2 1350 0.27 5 Michael Umana D 4 1 0 1037 0.17 5 Osvaldo Alonso M 6 3 2 2070 0.35 45 Paulo Nagamura M 5 0 1 506 0.18 8 James Riley D 7 0 1 1949 0.05 5 Mariano Trujillo D 8 1 0 248 0.73 3 Erik Friberg M 8 1 2 1454 0.25 8 Simon Elliott M 9 0 2 1340 0.13 15 Mauro Rosales F 10 3 7 1403 0.83 13 Nick LaBrocca M 10 7 4 2068 0.78 18 Leo Gonzalez D 12 0 1 808 0.11 3 Michael Lahoud M 11 1 1 1101 0.25 10 -

All-Time Numerical Roster (Since 1981)

All-Time Numerical Roster (since 1981) #00 Ramon Manak (04-05) Ryan Hollingshead (10-11-12) Brian Woolfolk (91-92-93-94) Kevin De La Torre (13-14) Kevin Weiner (07-08-09-10) Sean Alvarado (06-07-08-09) Gage Zerboni (13-14-15-16) Matt Reis (95-96) Alberto “Kike” Poleo (15-16) Jake Tenzer (11) Matt Wiet (10-11-12) #13 Nick Rimando (97) #24 Pepe Barroso Silva (14-15) Jordan Vale (13-14-15) Mark Clay (81-82-84-85) Stephen Gardner (98) Pat McLaughlin (88) #0 #7 Scott Barbour (83) Zach Wells (99-00) Matt Arya (90) Eric Conner (05) Tibor Pelle (81) Will Steadman (86) Nate Pena (02-03) Jay Kelly (93) Alex Padilla (13) Mike Arya (82-83) Brad McAdams (87) Mike Zaher (04) Eddie Salcedo (94) Brad Rusin (05) #1 Shaun Del Grande (84-86-87) J.B. Frost (88) Lars Ensberg (96) Chris Roosen (85) Paul Ratcliffe (89) Trevor Hunter (06-07) Craig Hart (97) John Glenn (81) Zack Zerrenner (08) Tim Harris (81-82-83) Tim Gallegos (88-89-90-91) Sean Henderson (90) Tim Pierce (98-99) Philip Button (92-93) Terry Shorter (91) Ryan Hollingshead (09) John Carson (00) David Vanole (81-82-84-85) Earl Edwards (10) Drew Leonard (83-84-85) Kenny Wright (94-95) Ante Razov (92) Ryan Valdez (03-04-05) Pete Vagenas (96-97-98-99) Caleb Meyer (93-94-95-96) Reed McKenna (11) David Estrada (06-07-08-09) Ed Austin (84) Alex Padilla (12) Anton Nistl (86-87-88-89) Ty Maurin (00-01-02-03) Nick Paneno (97-98-99) Reed Williams (10-11-12-13) Jonathan Bornstein (04) Matt Taylor (00) Brian Iloski (13-14) Nathan Smith (14-15) Nat Gonzalez (88-89-90-91) Jose Hernandez (15) Robert Silverman