September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Hole: the Fate of Islamists Rendered to Egypt

Human Rights Watch May 2005 Vol. 17, No. 5 (E) Black Hole: The Fate of Islamists Rendered to Egypt I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Torture in Egypt and the Prohibition Against Involuntary Return ................................. 5 The Prohibition against Refoulement.................................................................................... 8 The Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism................................................... 9 III. Who are the Jihadists? ......................................................................................................... 10 IV. The Role of the United States ............................................................................................ 13 V. Bad Precedent: The 1995 and 1998 Renditions ................................................................ 19 Tal`at Fu’ad Qassim ...............................................................................................................19 Breaking the Tirana Cell ........................................................................................................21 VI. Muhammad al-Zawahiri and Hussain al-Zawahiri .......................................................... 24 VII. From Stockholm to Cairo: Ahmad `Agiza and Muhammad Al-Zari`........................ 30 Ahmad `Agiza’s trial...........................................................................................................33 VIII. -

Crushing Humanity the Abuse of Solitary Confinement in Egypt’S Prisons

CRUSHING HUMANITY THE ABUSE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN EGYPT’S PRISONS Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2018 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Designed by Kjpargeter / Freepik https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2018 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 12/8257/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 10 BACKGROUND 12 ILLEGITIMATE USE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT 14 OVERLY BROAD SCOPE 14 ARBITRARY USE 15 DETAINEES WITH A POLITICAL PROFILE 15 PRISONERS ON DEATH ROW 20 ACTS NOT CONSTITUTING DISCIPLINARY OFFENCES 22 LACK OF DUE PROCESS 24 LACK OF INDEPENDENT REVIEW 24 LACK OF AUTHORIZATION BY A COMPETENT -

28 October 2019 Excellency, We Have the Honour to Address You in Our Capacities As Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention REFERENCE: AL EGY 9/2019 28 October 2019 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 35/15 and 33/30. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning conditions that appear to have led to the death of the former president of Egypt Mr. Mohamed Morsi Eissa El- Ayyat (Dr. Morsi) on 17 June 2019 and that appear to be currently endangering the lives of Dr. Essam El-Haddad, his son Mr. Gehad El-Haddad, and many other prisoners. Specifically, we bring to the attention of Your Excellency’s Government allegations that Dr. Morsi's conditions of detention, insufficient access to lawyers and family, deliberate denial of health care, and other acts potentially constituting torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment by the state of the Arab Republic of Egypt during Dr. Morsi’s nearly six years in custody may have caused his death. These same conditions and acts appear to be immediately threatening the lives of Dr. Essam El-Haddad and Mr. Gehad El-Haddad, as well as many other prisoners. The alleged facts constitute severe infringements of the right to life, the right not to be subjected to arbitrary detention, the right not to be subjected to torture or ill-treatment, the right to due process and a fair trial, and the right to health. -

Amnesty International Report

CRUSHING HUMANITY THE ABUSE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN EGYPT’S PRISONS Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2018 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Designed by Kjpargeter / Freepik https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2018 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 12/8257/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 10 BACKGROUND 12 ILLEGITIMATE USE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT 14 OVERLY BROAD SCOPE 14 ARBITRARY USE 15 DETAINEES WITH A POLITICAL PROFILE 15 PRISONERS ON DEATH ROW 22 ACTS NOT CONSTITUTING DISCIPLINARY OFFENCES 23 LACK OF DUE PROCESS 25 LACK OF INDEPENDENT REVIEW 25 LACK OF AUTHORIZATION BY A COMPETENT -

THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION of OSAMA BIN LADEN by Copyright 2008 Christopher R. Carey Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program In

THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION OF OSAMA BIN LADEN BY Copyright 2008 Christopher R. Carey Submitted to the graduate degree program in International Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. ___Dr. Rose Greaves __________________ Chairperson _Dr. Alice Butler-Smith ______________ Committee Member _ Dr. Hal Wert ___________________ Committee Member Date defended:___May 23, 2008 _________ Acceptance Page The Thesis Committee for Christopher R. Carey certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION OF OSAMA BIN LADEN _ Dr. Rose Greaves __________ Chairperson _ _May 23, 2008 ____________ Date approved: 2 Abstract Christopher R. Carey M.A. International Studies Department of International Studies, Summer 2008 University of Kansas One name is above all others when examining modern Islamic fundamentalism – Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden has earned global notoriety because of his role in the September 11 th attacks against the United States of America. Yet, Osama does not represent the beginning, nor the end of Muslim radicals. He is only one link in a chain of radical thought. Bin Laden’s unorthodox actions and words will leave a legacy, but what factors influenced him? This thesis provides insight into understanding the ideological foundation of Osama bin Laden. It incorporates primary documents from those individuals responsible for indoctrinating the Saudi millionaire, particularly Abdullah Azzam and Ayman al-Zawahiri. Additionally, it identifies key historic figures and events that transformed bin Laden from a modest, shy conservative into a Muslim extremist. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not be possible without inspiration from each of my committee members. -

Download the Full Report

HUMAN RIGHTS “We are in Tombs” Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison WATCH “We Are in Tombs” Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34051 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2016 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34051 “We Are in Tombs” Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison Map .................................................................................................................................... I Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 10 To Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi .............................................................................. -

Egypt: the Trial of Hosni Mubarak Questions and Answers

Egypt: The Trial of Hosni Mubarak Questions and Answers May 2012 Hosni Mubarak, 84, became president of Egypt after the assassination of Anwar Sadat in October 1981, and served until he was ousted on February 11, 2011, following the large- scale pro-democracy protests that began on January 25 (the “January 25 protests”). A career military officer and commander of the Egyptian Air Force, he had been named vice- president in 1975. 1. What are the charges against Mubarak? Mubarak is charged with complicity in the murder and attempted murder of hundreds of peaceful demonstrators protesting his rule in Cairo, Alexandria, Suez, and several other Egyptian governorates between January 25 and January 31, 2011, under Articles 40(2), 45, 230, 231, and 235 of the Egyptian Penal Code. Although there were further injuries and deaths in the continuing protests against Mubarak’s rule after January 31 and prior to his departure, the charges only concern events though January 31. Article 40(2) establishes criminal liability for any person who agrees with another to commit a crime that takes place on the basis of such agreement. Article 45 defines “attempt” as the beginning of carrying out an act with the intent to commit a crime. Articles 230 and 231 provide that the death penalty is the punishment for premeditated murder. Article 235 specifies that the accomplices to premeditated murder shall be sentenced to death or life in prison. That said, it should be noted that Penal Code article 17 gives the court discretion to substitute a prison sentence for a death sentence and a lesser sentence for a sentence of life in prison. -

Businessmen and Authoritarianism in Egypt

Businessmen and Authoritarianism in Egypt Safinaz El Tarouty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of East Anglia, School of Political, Social and International Studies. Norwich, May 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract The main concern of this thesis is to examine how the Mubarak authoritarian regime survived for three decades, especially after the introduction of economic liberalization. I argue that the Mubarak regime created a new constituency of businessmen who benefited from economic reform and in return provided support to the regime. Based on interviews with Egyptian businessmen and political activists, this thesis examines the different institutional mechanisms used by the regime to co-opt businessmen and based on predation of public and private resources. Extending the literature on clientelism, I create a typology of regime-businessmen relations in terms of authoritarian clientelism, semi-clientelism, patron-broker client relationships, and mutual dependency. The thesis further examines how the regime dealt with an opposition that refused to enter into its clientelisitic chain. I demonstrate how the regime weakened this opposition by creating among them a divided political environment on different levels (i.e., among the legal and illegal opposition, inside the legal opposition, and among the illegal opposition). This thesis demonstrates that there are businessmen who are supportive of authoritarianism; however, they may also oppose authoritarian regimes, not for their own business interests but rather for their own political/ideological stance. -

Egypt: Opposition to State

Country Policy and Information Note Egypt: Opposition to state Version 1.0 July 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive)/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

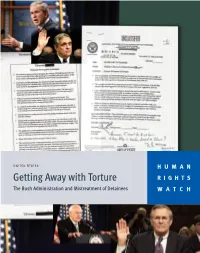

Getting Away with Torture RIGHTS the Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees WATCH

United States HUMAN Getting Away with Torture RIGHTS The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees WATCH Getting Away with Torture The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-789-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-789-2 Getting Away with Torture The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 12 I. Background: Official Sanction for Crimes against Detainees .......................................... 13 II. Torture of Detainees in US Counterterrorism Operations ............................................... 18 The CIA Detention Program ....................................................................................................... -

MOHAMED SOLTAN, ) 2907 Bleeker St

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ ) MOHAMED SOLTAN, ) 2907 Bleeker St. ) Fairfax, VA 22031 ) Civil ACtion No.: Plaintiff, ) ) COMPLAINT PURSUANT TO TORTURE v. ) VICTIM PROTECTION ACT ) ) HAZEM ABDEL AZIZ EL BEBLAWI, ) ) Defendant. ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ) Plaintiff MohaMed Soltan, for his Complaint in the above-Captioned Matter, states and alleges as follows: PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1. This is a Civil aCtion for Compensatory and punitive daMages brought by Plaintiff MohaMed Soltan, a Citizen of the United States, under the Torture ViCtiM ProteCtion ACt (“TVPA”), Pub. L. No. 102-256, 106 Stat. 73 (1992) (codified at, 28 U.S.C. §1350). Plaintiff is a Citizen of the United States who was alMost killed, brutally wounded, iMprisoned and tortured for nearly two years in Egypt beCause he dared to expose to the world the Egyptian Military government’s brutal suppression and MassaCre of peaCeful deMonstrators. That suppression and MassaCre, as well as Plaintiff’s iMprisonment, torture and near death, were the direCt results of aCtions taken by the highest levels of the Egyptian government, including, signifiCantly, by Defendant HazeM Abdel Aziz El Beblawi, the former Egyptian PriMe Minister. 1 2. Defendant Beblawi iMprisoned, tortured and approved the targeted assassination of Plaintiff (whiCh failed only by happenstance as desCribed below), aCting in ConspiraCy with un- sued Defendants Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Current Egyptian President and former Deputy PriMe Minister for SeCurity -

Like a Fire in a Forest: ISIS Recruitment in Egypt's Prisons

Like a Fire in a Forest ISIS Recruitment in Egypt’s Prisons FEBRUARY 2019 ON HUMAN RIGHTS, the United States must be a beacon. We know that it is not enough to expose and protest Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to injustice, so we create the political environment and policy look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect for human Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a rights. Whether we are protecting refugees, combating vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies torture, or defending persecuted minorities, we focus not on and actions match our values. making a point, but on making a difference. For over 30 Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action years, we’ve built bipartisan coalitions and teamed up with organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. frontline activists and lawyers to tackle issues that demand We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle American leadership. for human rights so we press the U.S. government and Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan international private companies to respect human rights and the rule of human rights organization based in New York and law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept accountability, and justice. Around the world, we work where no government funding. we can best harness American influence to secure core © 2019 Human Rights First All Rights Reserved. freedoms.