Stuart Davis Press Highlights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart Davis (1892–1964) by Lisa Bush Hankin

fine art as an investment Stuart Davis (1892–1964) by Lisa Bush Hankin leading member of the first genera- with a current record auction price of four and family friends Robert Henri (1865–1929) and tion of artists who put a distinctly a half million dollars (Fig. 1). John Sloan (1871–1951), whose early artistic A American spin on the modernist ideas Born in Philadelphia, Davis was the son of support enabled the young man to participate then percolating in Europe, Stuart Davis is cel- professional artists (a sculptor and the art in prominent exhibitions including the ebrated for his lively and colorful canvases that director for the Philadelphia Press), who relo- groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show, an event incorporate imagery from the American pop- cated to northern New Jersey, outside New that profoundly affected the direction his art ular culture of his day. Davis is seen as a York City, when Davis was nine. Davis bene- would take. Though Davis’ early works reflect seminal figure in early modernism, and his fited early in his career from the guidance of the influence of the Ashcan school (Fig. 2), he works are highly sought after by both museums soon chose to depart from representing his and collectors. As a result, his major paintings Stuart Davis subjects in an illusionistic manner, dispensing Record Prices for Work at Auction do not appear on the market very frequently, with 3-dimensional form in favor of using and — as back-to-back multimillion dollar Present $4,500,000 line, color, and pattern to capture the energy 2005 $2,400,000 sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the fall of Fig. -

Exhibition Image Captions

Contacts: Mike Brice Stephanie Elton EXHIBITION Public Relations Specialist Director of Communications IMAGE CAPTIONS 419-255-8000 x7301 419-255-8000 x7428 [email protected] [email protected] Life Is a Highway: Art and American Car Culture 1. Don Eddy (American, born 1944), Red Mercedes. Color lithograph, 1972. 24 1/8 x 30 11/16 in. (61.3 x 78 cm). Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio), Frederick B. and Kate L. Shoemaker Fund, 1974.36. © Don Eddy Image Credit: Christopher Ridgway 2. Robert Indiana (American, 1928–2018), South Bend. Color lithograph, 1978. 30 x 27 15/16 in. (76.2 x 71 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Gift of Art Center, Inc., 1978.63. © Morgan Art Foundation Ltd. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 3. Claes Oldenburg (American, born Sweden, 1929), Profile Airflow. Cast polyurethane relief over two-color lithograph, 1969. 33 1/4 x 65 1/2 x 3 3/4 in. (84.5 x 166.4 x 9.5 cm). Collection of the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, MI; Museum purchase. © 1969 Claes Oldenburg 1 of 3 4. Kerry James Marshall (American, born 1955), 7am Sunday Morning. Acrylic on canvas banner, 2003. 120 x 216 in. (304.8 x 548.6 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Joseph and Jory Shapiro Fund by exchange, 2003.16. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. 5. Helen Levitt (American, 1913–2009), New York City (Spider Girl). Chromogenic color print, 1980. 12 1/4 × 18 in. (31.1 × 45.7 cm). Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Frederick B. -

Swing Landscape

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Stuart Davis American, 1892 - 1964 Study for "Swing Landscape" 1937-1938 oil on canvas overall: 55.9 × 73 cm (22 × 28 3/4 in.) framed: 77.8 × 94.6 × 7 cm (30 5/8 × 37 1/4 × 2 3/4 in.) Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase and exchange through a gift given in memory of Edith Gregor Halpert by the Halpert Foundation and the William A. Clark Fund) 2014.79.15 ENTRY Swing Landscape [fig. 1] was the first of two commissions that Stuart Davis received from the Mural Division of the Federal Art Project (FAP), an agency of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), to make large-scale paintings for specific sites in New York. The other was Mural for Studio B, WNYC, Municipal Broadcasting Company [fig. 2]. [1] The 1930s were a great era of mural painting in the United States, and Davis, along with such artists as Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889 - 1975), Arshile Gorky (American, born Armenia, c. 1902 - 1948), and Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913 - 1980), was an important participant. In the fall of 1936, Burgoyne Diller (American, 1906 - 1965), the head of the Mural Division and a painter in his own right, convinced the New York Housing Authority to commission artists to decorate some basement social rooms in the Williamsburg Houses, a massive, new public housing project in Brooklyn. A dozen artists were chosen to submit work, and, while Davis’s painting was never installed, it turned out to be a watershed in his development. -

HETAG: the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group

HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Jack Key Flanagan [Townscape] c.1946 HETAG Newsletter November/December 2017 Here it is almost the end of another year. Yes, they do fly by, but there’s no time to dwell on that. As you will see later in the newsletter, planning is already well underway on a number of fronts for exciting HETAG, CASETA and other exhibitions, gatherings and publications in 2018 relating to Earlier Houston and Early Texas Art. Stay tuned for another exciting year. The newsletter image theme for this issue: Works by some Earlier Houston Artists you may never have heard of. Plus a recreation of a special Emma Richardson Cherry exhibition at the end. Charles Allyn Gordon [Farmhouse] c.1935-1940 (l); Florence B. Grant Winter in Houston c.1943 (r) HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Upcoming HETAG meeting: Our next HETAG meeting will be a visit to Betty Moody Gallery 2815 Colquitt St., Houston Sunday January 7, 2018, at 2:30 p.m. Betty will welcome us for a look at the amazing paintings by Sarah Williams Sarah Williams Abilene 2017 Oil on Board 18x24 And the end-of-year gallery artist group exhibition. There will be lots of fun and fascinating stories about the Houston art scene going back a few years, as only Betty can tell them. Michael Kennaugh Beyond Delta 2017 (l); Lucas Johnson La Entrada 1977 (r) Jim Love Ash Tray/Candle Holder 1957 HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group “Planned, Organized and Established: Houston Artist Cooperatives of the 1930s,” like all good things (as the saying goes), has come to an end. -

Retrospective Exhibit of Stuart Davis

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ACRTMMEDIATE RELEASE tl WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. ELEPHONE: MfAggP^ e8& MODERN ART PRESENTS ONE-MAN RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY STUART DAVIS Stuart Davis is a painter of the American scene. Through his art he translates its spirit and its rhythms into paint. As he expresses it: "I have enjoyed the dynamic American scene for many years, and all my pictures (including the ones I painted in Paris) are referential to it. They all have their originating impulse in the impact of contemporary American environment. Some of the things that have made me want to paint, outside of other paintings are: American wood and iron work1 of the past; Civil War and skyscraper architecture; the brilliant colors on gasoline stations, chain store fronts, and taxicabs; the music of Bach; synthetic chemistry; ... fast travel "by train, auto and aeroplane which has brought new and multiple perspectives; electric signs; the landscape and boats of Gloucester, Massa chusetts; five-and-ten-cent store kitchen utensils; movies and radio; Earl Hines1 hot piano and Negro Jazz music in general, etc." A one-man show of Stuart Davis' work will open at the Museum of Modern Art Wednesday, October 17. It will cover his production from Self-Portrait painted in 1912 when the artist was only eighteen, to paintings of 1945—showing a cross-section of the work which has caused Davis to be regarded as one of the leaders of American art. The exhibition, which will remain'on.view through February 3, 1946, will consist of approximately fifty oil paintings, mural panels, drawings and watercolors. -

Get Smart with Art Is Made Possible with Support from the William K

From the Headlines About the Artist From the Artist Based on the critics’ comments, what aspects of Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) is Germany in 1830, Albert Bierstadt Bierstadt’s paintings defined his popularity? best known for capturing majestic moved to Massachusetts when he western landscapes with his was a year old. He demonstrated an paintings of awe-inspiring mountain early interest in art and at the age The striking merit of Bierstadt in his treatment of ranges, vast canyons, and tumbling of twenty-one had his first exhibit Yosemite, as of other western landscapes, lies in his waterfalls. The sheer physical at the New England Art Union in power of grasping distances, handling wide spaces, beauty of the newly explored West Boston. After spending several years truthfully massing huge objects, and realizing splendid is evident in his paintings. Born in studying in Germany at the German atmospheric effects. The success with which he does Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Bierstadt this, and so reproduces the noblest aspects of grand returned to the United States. ALBERT BIERSTADT scenery, filling the mind of the spectator with the very (1830–1902) sentiment of the original, is the proof of his genius. A great adventurer with a pioneering California Spring, 1875 Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 84¼ in. There are others who are more literal, who realize details spirit, Bierstadt joined Frederick W. Lander’s Military Expeditionary Presented to the City and County of more carefully, who paint figures and animals better, San Francisco by Gordon Blanding force, traveling west on the overland who finish more smoothly; but none except Church, and 1941.6 he in a different manner, is so happy as Bierstadt in the wagon route from Saint Joseph, Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, San Francisco. -

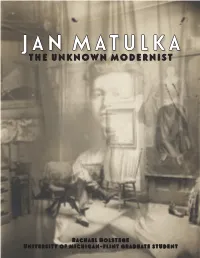

JAN MATULKA the Unknown Modernist

JAN MATULKA the unknown modernist Rachael Holstege University of michigan-flint graduate stUdent This online catalogue is published in conjunction with exhibition Jan Matulka: The Unknown Modernist presented at the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, Michigan. Jan Matulka loans courtesy of McCormick Gallery, Chicago. Copyright © 2020 Rachael Holstege. All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or in any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the author. Rights and reproductions: © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 10) © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 12) © Estate of Stuart Davis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 17) Cover: Double-exposed portrait of Jan Matulka, c. 1920. Jan Matulka papers, 1923-1960. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. contents PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION 5 THE YOUNG ARTIST 6 LE TYPE TRANSATLANTIQUE 8 THE NEW SPIRIT 11 LASTING LEGACY 13 ABSTRACTED CONCLUSION 16 CATALOGUE 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 III PREFACE I first read the name Jan Matulka while nature of art history, Matulka is continually looking through the Flint Institute of Arts forgotten. This exhibition looks to reinforce database of the nearly 9,000 artworks in his role in the pivotal decades of the their collection. Eager to find a compelling development of modern art and reinforce artist or subject to base my research on, his importance in the oeuvre of art history. I was continually drawn to two works in the collection by Czech-American artist This catalogue and accompanying exhibition Jan Matulka. -

Talk About Art with Your Child and Help Them Develop Critical Thinking Skills!

Stuart Davis based The Mellow Pad on an earlier piece of artwork and, like jazz, used improvisation to grow the artwork. • What shapes do you see? • What would this painting Stuart Davis sound like if it were music? 1892 – 1964, Philadelphia, PA Wassily Kandinsky Stuart Davis • How many letters can you find? Swing Landscape, 1938 1866 – 1944, Russia 1892 – 1964, Philadelphia, PA American Cubism Succession, 1935 The Mellow Pad, 1951 Stuart Davis’ artwork was inspired Biomorphic Abstraction American Cubism by the improvisational character Wassily Kandinsky was a Russian of jazz music. His use of color painter and art theorist for and shape was inspired by the whom music and color were Talk about art with notes and rhythm of the music. connected. He had a condition • What everyday objects do you called synesthesia, where he saw your child and help see in this painting? color when he heard music. He them develop critical • How does this make you feel? associated each music note with Why? an exact hue. thinking skills! • How would this painting • What does this painting sound sound if it were a piece like to you? of music? • Is the music slow or fast? Look at artwork with Joyful or somber? Neither? Joseph Catanzaro David Ralph your child and ask • How would you draw your Chicago, IL Born 1964, Red Bank, NJ these questions*: favorite song? Four Musicians Delta Blues Contemporary Cubism Geoformism 1. What’s going on in Joseph Catanzaro combines David Ralph spends a lot of Boaz Klachkin his love of music, cartoons, time thinking about the shapes this picture? Born 1953, Israel comic books, and play with and colors he will use to create String Orchestra, 1983 Pablo Picasso’s visual language his subject matter. -

Down from the Ivory Tower: American Artists During the Depression

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression Susan M. Eltscher College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Eltscher, Susan M., "Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a5rw-c429 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOWN FROM THE IVORY TOWER: , 4 ‘ AMERICAN ARTISTS DURING THE DEPRESSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan M. Eltscher APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^jiuu>0ur> H i- fc- bbcJ^U i Author Approved, December 1982 Richard B. Sherman t/QOJUK^r Cam Walker ~~V> Q ' " 9"' Philip J/ Fuiyigiello J DEDICATION / ( \ This work is dedicated, with love and appreciation, to Louis R. Eltscher III, Carolyn S. Eltscher, and Judith R. Eltscher. ( TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACRONYMS................... .......................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... -

Exhibitions (January 18–July 14)

Exhibitions (January 18–July 14): Sheldon Treasures th Stuart Davis: Arch Hotel (closing May 5 ) Table Manners: Art and Food John Walker: Moments of Observation Spring 2019 Quick Guides Sheldon Treasures Introductory Label Sheldon Museum of Art is home to two collections of art. In addition to objects acquired by the University of Nebraska, the museum stewards a collection assembled by the Sheldon Art Association, an organization founded in 1888 as the Haydon Art Club to promote the fine arts in Nebraska. Together, the collections comprise holdings of nearly 13,000 original works of art in various media. Each collection includes unparalleled treasures. Some are unique masterworks by renowned artists; others are beloved favorites of museum visitors. Many have traveled great distances to be seen in national and international exhibitions. This gallery presents a selection of such objects, a testament to the wisdom and foresight of Sheldon’s leaders and advocates who have assembled these works for the benefit of future generations. Ideas to Explore with Students • Abstract vs. representational art • History of Sheldon Museum of Art • The museum’s role in the community • What makes a “treasure?” • The role of the curator: If you were a curator, what choices would you make? • The context (historical, social, cultural) of art • Representations of the human body • Introspection: How do artists give the impression of someone lost in thought? • The African American experience throughout history • The lack of representation of women and African Americans in the art world, including museums: Why is it important that this gallery include works by and about women and people of color? • Art and politics Helpful to Know • The thumbnail images from treasure labels will be available as laminates for docent tours • Both Barkley Hendricks and Robert Indiana passed away in 2018. -

Walt Kuhn & American Modernism

Walt Kuhn & American Modernism 80.15, Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), Floral Still Life, oil, 1920, Gift of Mrs. John D. West 89.8.2, Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), Pink Blossom, oil, 1920, Gift of Mrs. John D. West. These two paintings were created by the same artist, in the same year, and have basically the same subject matter, yet they are extremely different. Take a moment to look closely at them. How did the artist use paint to create shapes and space in each work? What is the overall emotional impact of these styles? Walt Kuhn was an artist during in the development of American Modernism: the breaking away of American artists from working in the traditional, realistic style of the academy with an emphasis on creating beauty. The new pieces began experimenting with abstraction of image: altering aspects of the subject so it looks different than to what it looks like in “real” life. Abstraction can be achieved in many ways, by using non-naturalistic color, exaggerating scale of some aspects of a subject, or by flattening the forms into two dimensional shapes and breaking the subject down into essential lines and shapes. On the left, Kuhn works in a traditional style of painting. The colors of the subject are true to life and generally depicted in a realistic style. One could argue he has been influenced a bit by the loose brushwork of the Impressionists, but overall the painting is quite traditional and depicts depth and texture one would expect from a still-life of flowers. On the right, the background has been reduced to flat areas of color. -

John Sloan and Stuart Davis Is Gloucester: 1915-1918

JOHN SLOAN AND STUART DAVIS IS GLOUCESTER: 1915-1918 A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts by Kelly M. Suredam May, 2013 Thesis written by Kelly M. Suredam B.A., Baldwin-Wallace College, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by _____________________________, Advisor Carol Salus _____________________________, Director, School of Art Christine Havice _____________________________, Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………..………...iii LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………….…………….iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………….xii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF GLOUCESTER……………………………………….....6 II. INFLUENCES: ROBERT HENRI, THE ASHCAN SCHOOL, AND THE MARATTA COLOR SYSTEM……………………………………………………..17 III. INFLUENCES: THE 1913 ARMORY SHOW………………………………….42 IV. JOHN SLOAN IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………...54 V. STUART DAVIS IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………76 VI. CONCLUSION: A LINEAGE OF AMERICAN PAINTERS IN GLOUCESTER………………………………………………………………………97 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………..112 FIGURES…………………………………………………………………………………...118 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. John Sloan, Near Sunset, Gloucester, 1914-1915………………..………..………..……118 2. Stuart Davis, Gloucester Environs, 1915……………………………………..………….118 3. Map of Gloucester, Massachusetts………………………………………….…...............119 4. Cape Ann Map…………………………………………………………………………...119 5. Map of the Rocky