Translation of Bhakti Poetry Into English: a Case Study of Narsinh Mehta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iasbaba's 60 Days Plan – Day 48 (History)

IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – Day 48 (History) 2018 Q.1) Consider the following pairs about Sufi philosophy. Philosophy Meaning 1. Waḥdat al-wujūd Unity of Existence 2. Waḥdat ash-shuhūd Unity of appearance 3. Al-Wujūd Al-Munbasiṭ Self-unfolding Being Which of the above pairs is/are correctly matched? a) 1 only b) 1 and 2 only c) 1, 2 and 3 d) 3 only Q.1) Solution (c) Major ideas in Sufi metaphysics have surrounded the concept of weḥdah meaning "unity", or in Arabic tawhid. Two main Sufi philosophies prevail on this topic. waḥdat al-wujūd literally means the "Unity of Existence" or "Unity of Being" but better translation would be Monotheism of Existence. Wujud (i.e. existence) here refers to Allah's Wujud - implication is Wahdat/Tawheed Of Wujud Of Allah. On the other hand, waḥdat ash-shuhūd, meaning "Apparentism" or "Monotheism of Witness", holds that God and his creation are entirely separate. Al-Wujūd Al-Munbasiṭ (Self-unfolding Being) Shah Waliullah Dehlawi tried to reconcile the two (apparently) contradictory doctrines of waḥdat al-wujūd (unity of being) of Ibn Arabi and waḥdat ash-shuhūd (unity in conscience) of Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi. Shah Waliullah neatly resolved the conflict, calling these differences 'verbal controversies' which have come about because of ambiguous language. If we leave, he says, all the metaphors and similes used for the expression of ideas aside, the apparently opposite views of the two metaphysicians will agree. Do you know? While orthodox Muslims emphasise external conduct, the Sufis lay stress on inner purity. While the orthodox believe in blind observance of rituals, the Sufis consider love and devotion as the only means of attaining salvation. -

Narsinh Mehta - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Narsinh Mehta - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Narsinh Mehta(1414? – 1481?) Narsinh Mehta (Gujarati:?????? ?????)also known as Narsi Mehta or Narsi Bhagat was a poet-saint of Gujarat, India, and a member of the Nagar Brahmins community, notable as a bhakta, an exponent of Vaishnava poetry. He is especially revered in Gujarati literature, where he is acclaimed as its Adi Kavi (Sanskrit for "first among poets"). His bhajan, Vaishnav Jan To is Mahatma Gandhi's favorite and has become synonymous to him. <b> Biography </b> Narsinh Mehta was born in the ancient town of Talaja and then shifted to Jirndurg now known as Junagadh in the District of Saurashtra, in Vaishnava Brahmin community. He lost his mother and his father when he was 5 years old. He could not speak until the age of 8 and after his parents expired his care was taken by his grand mother Jaygauri. Narsinh married Manekbai probably in the year 1429. Narsinh Mehta and his wife stayed at his brother Bansidhar’s place in Junagadh. However, his cousin's wife (Sister-in-law or bhabhi) did not welcome Narsinh very well. She was an ill- tempered woman, always taunting and insulting Narsinh mehta for his worship (Bhakti). One day, when Narasinh mehta had enough of these taunts and insults, he left the house and went to a nearby forest in search of some peace, where he fasted and meditated for seven days by a secluded Shiva lingam until Shiva appeared before him in person. -

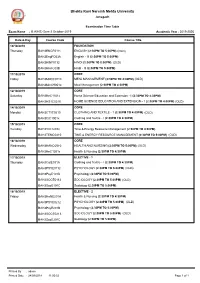

1570012789 UG Sem-3 October-2019 Exam Time Table.Pdf

Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University Junagadh Examination Time Table Exam Name : B.A(HS) Sem-3 October-2019 Academic Year : 2019-2020 Date & Day Course Code Course Title 10/10/2019 FOUNDATION Thursday BAH3ENGF0111 ENGLISH (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3EngFC03A English - III (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) BAH3HINF0112 HINDI (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3HinFC03B Hindi - III (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) 11/10/2019 CORE Friday BAH3MM0C0110 MEAL MANAGEMENT (2:30PM TO 4:00PM) (OLD) BAH3MmC9001x Meal Management (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) 12/10/2019 CORE Saturday BAH3HeC1101x Home Science Education and Extension - I (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) BAH3HS1C0310 HOME SCIENCE EDUCATION AND EXTENSION - 1 (2:30PM TO 4:00PM) (OLD) 14/10/2019 CORE Monday BAH3CT1C0210 CLOTHING AND TEXTILE - 1 (2:30PM TO 4:00PM) (OLD) BAH3CtC1001x Clothing and Textile - I (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) 15/10/2019 CORE Tuesday BAH3TeC1201x Time & Energy Resource Management (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) BAH3TEMC0410 TIME & ENERGY RESOURCE MANAGEMENT (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) 16/10/2019 CORE Wednesday BAH3HANC0510 HEALTH AND NURSING (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3HnC1301x Health & Nursing (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) 17/10/2019 ELECTIVE - 1 Thursday BAH3CatE101A Clothing and Textile - I (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) BAH3PSYE0112 PSYCHOLOGY (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3PsyE101B Psychology (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) BAH3SOCE0113 SOCIOLOGY (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3SocE101C Sociology (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) 18/10/2019 ELECTIVE - 2 Friday BAH3HaNE201A Health & Nursing (2:30PM TO 4:30PM) BAH3PSYE0212 PSYCHOLOGY (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3PsyE201B Psychology (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) BAH3SOCE0213 SOCIOLOGY (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) (OLD) BAH3SocE201C Sociology (2:30PM TO 5:00PM) Printed By : admin Printed Date : 24/09/2019 11:00:52 Page 1 of 1 Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University Junagadh Examination Time Table Exam Name : B.A. -

Limnological Studies of Narsinh Mehta Lake of Junagadh District in Gujarat, India

International Research Journal of Environment Sciences________________________________ ISSN 2319–1414 Vol. 2(5), 9-16, May (2013) Int. Res. J. Environment Sci. Limnological studies of Narsinh Mehta Lake of Junagadh District in Gujarat, India 1* 2 2 2 3 Khwaja Salahuddin , Soni Virendra , Visavadia Manish , Gosai Chirag and Syed Mohammad Zofair 1* Department of Botany, Bahauddin Science College, Junagadh-362001, Gujarat, INDIA 2 Department of Zoology, Bahauddin Science College, Junagadh-362001, Gujarat, INDIA 3Dept. of Harvest and Post Harvest Technology, College of Fisheries, Junagadh Agricultural University, Veraval, Gujarat, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 20 th February 2013, revised 27 th March 2013, accepted 25 th April 2013 Abstract The present study was carried out for ascertaining the quality of water for the purpose of the conservation of Narsinh Mehta Lake of Junagadh. Several physicochemical parameters such as pH, total alkalinity, total hardness, total dissolved solids, chloride content, dissolved oxygen (DO), biochemical oxyen demand (BOD) were meticulously observed in different seasons for the year 2012. The dissolved oxygen was found to be the highest (7.8 mgl -1) and the lowest (6.4 mgl -1) in winter and summer season, respectively. Likewise, Biochemical oxygen demand was recorded to be the lowest (15.20 mgl -1) and the highest (25.67 mgl -1) in monsoon season and summer season, respectively. DO showed negative correlation ( r = - 0.71 ) with BOD. Water quality index was estimated and its value was found in the range of 169.93 to 256.97 in monsoon and summer season, respectively which indicated much pollution in the lake. -

Bhakti Movement in India and Contributions to Gujarati Bhakti Poetry by Narsinh Mehta and Gangasati

BHAKTI MOVEMENT IN INDIA AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO GUJARATI BHAKTI POETRY BY NARSINH MEHTA AND GANGASATI Prof. Ami Upadhyay Dr. Dushyant Nimavat Abstract: The devotional literature we find in India's regional languages is sometimes referred to as Bhakti's literature. Since the poets from Bhakti Panth are more social and cultural, they are more thinkers and more social than literary figures. The translation of classics is particularly meaningful when a native language is translated into English. The classics are introduced to the world. In contemporary Shri Aurobindo and Dilp Chitre did, what Hsuan-tsang did for Sanskrit scripts. A. K. Ramanujan has also made a strong flow of translation in the post-colonial literature and Bhakti has been one of these literatures. This article explores the devotional poems of Narsinh Mehta that are important even in the 21st century. Keywords: Bhakti Tradition, Bhakti poetry, Narsinh Mehta and Gangasati, Bhajans Bhakti poems played a major role in regional language development, because they highlighted the everyday language of the people and rejected the Sanskrit elite tradition. Bhakti questioned the caste system, as many of his poets came from the lower castes and the poetry's main theme is that in every individual God is. Some of Tamil was some of the earliest bhakti poetry. Out of the A.D. In 900, with the literature of devotion as the Vachanas, Kannada became an important influence of the saints of different Hindu sects. The mediaeval poets Basavanna and Allama Prabhu are popular Kannada. Sept, 2020. VOL.12. ISSUE NO. 4 https://hrdc.gujaratuniversity.ac.in/Publication Page | 105 Towards Excellence: An Indexed, Refereed & Peer Reviewed Journal of Higher Education / Prof. -

Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University Junagadh

Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University Junagadh Examination Time Table Exam Name : B.A Sem-3 December-2020 Academic Year : 2020-2021 Date & Day Course Code Course Title 24/12/2020 FOUNDATION Thursday BA03EngF301x ENG Foundation English-3 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03HinF301x HIN Aekanki Sangrah-Panch Parde Aevam Bhasha Pravidhi Sn. Mohan Rakesh (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA3EngFO1010 FOUNDATION : ENGLISH (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) (OLD) BA3HinFO1010 FOUNDATION : HINDI (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) (OLD) 26/12/2020 CORE Saturday BA03EcoC105x ECO P5 Theories of Macro Economics - 1 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03EngC105x ENG P5 English Literature (Restoration Age 1660 to 1700) (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03GeoC105x GEO P5 Elements of Climatology (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03GujC105A GUJ P5 Granthkar : Pannalal Patel Vineli Navalika (Kruti) (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03GujC105B GUJ P5 Lokshahitya Bhag-3 Lokkatha Bhag-1 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03HinC105x HIN P5 Chhayavadi Kavya Sangrah-Lahar Sn.Jayprakash Prasad (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03HisC105x HIS P5 British History of India (1757 - 1885 A.D.) (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03PhiC105x PHI P5 Indian Philosophy - 1 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03PscC105x POL P5 IndianGovernment and Politics-1 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03PsyC105x PSY P5 Social Psychology (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03SanC105x SAN P5 Kalidas Rachit Abhignan Shakuntlam (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA03SocC105x SOC P5 Rural Sociology (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) BA3EcoC10510 MACRO ECONOMICS-1 (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) (OLD) BA3EngC10510 LATERARY FORM: COMEDY (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) (OLD) BA3GeoC10510 ELEMENTS OF CLIMATOLOGY (3:00PM TO 4:30PM) (OLD) BA3GujC10511 -

PART I 1. Narsinh Mehta

17 (2014) 104-158 rivista di ricerca teologica Premras påne tu morna picchadhar1 Gems of Bhakti Mysticism of Narsinh Mehta in the Letters of Francis Xavier by ROLPHY PINTO* Introduction To be religious in the postmodern times is to be interreligious.2 The saints in a given religion are the epitomes of their respective faith tradition. They live out one or more core tenets of their religious tradition in exemplary way. The saints give to the world a glimpse of the authenticity of their religion. The study of saints becomes a channel to grasp the pearls of wisdom of the religion they profess. While the nature of this article is interreligious, the scope is to restore the distorted image of Francis Xavier. He is perceived by some to be too aggressive in his missionary methods. For some, he is an ally of the Portuguese conquerors. A Hindu writer even brands him “a pirate in priest’s clothing”.3 To arrive at the desired end the method employed will be comparative. Francis Xavier will be compared with Narsinh Mehta, a man widely acclaimed as a bhakta4 and a saint. The purpose of the comparison is to glean from the Letters of Francis Xavier elements of bhakti mysticism and to redefine the spirituality of Xavier as a bhakti spirituality. This article seeks to answer the question, can Xavier be called a bhakta in the way Mehta is bhakta? * ROLPHY PINTO, docente di teologia presso l’Istituto di Spiritualità della Pontificia Università Gre- goriana; [email protected] 1 A line from padas of Mehta. -

Prelim Bits 20-08-2021 | UPSC Daily Current Affairs Narsinh Mehta River

Prelim Bits 20-08-2021 | UPSC Daily Current Affairs India Cooling Action Plan The 20-year India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP) was released by Ozone Cell of the Environment Ministry in 2019. The ICAP aims to bring down the refrigerant demand by 25 to 30% in the next 20 years. It aims to recognize “cooling and related areas” as a thrust area of research under the National S&T Programme. It describes cooling as a “developmental need” and seeks to address the rising demand in cooling, from buildings to transport to cold-chains, through sustainable actions. The plan estimates that the national cooling demand would grow 8 times in the next 20 years, which would result in a corresponding 5 to 8-fold rise in the demand for refrigerants that involve the use of HFCs. As part of the ICAP, the government has also announced targeted R&D efforts aimed at developing low-cost alternatives to HFCs. Such efforts are already underway at the Hyderabad-based Indian Institute of Chemical Technology and IIT Bombay. Other objectives - It will assess the cooling requirements across sectors and the associated refrigerant demand and energy use. The goals emerging from the suggested interventions stated in ICAP are, Goals Targets 20% to 25 % by Reduction of cooling demand across sectors 2037-38 25% to 30% by Reduction of refrigerant demand 2037-38 25% to 40% by Reduction of cooling energy requirements 2037-38 Skilling and certifying 100,000 Refrigeration and AC servicing sector technicians, in synergy with 2022-23 Skill India Mission Kigali Amendment Recently, India has ratified the Kigali Amendment to the 1989 Montreal Protocol for protection of the ozone layer. -

Preservation of Kathiawari Folk Literature and Arts

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 8 (4), October 2009, pp. 626-628 Preservation of Kathiawari folk literature and arts Puffy I Dave Department of Extension Education, College of Agriculture, Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh 362 001 Gujarat E-mail: [email protected] Received 13 July 2007; revised 12 June 2008 Kathiawar, known as Saurashtra region in Gujarat, is rich in its cultural heritage of folk arts and literature. The folk dances of Kathiawar like dandiya raas, garba , etc. folk music like bhajans, dohas , etc, litterateurs like Zaverchand Meghani, Narsinh Mehta, Bhoja Bhagat, Dulabhai Kag, etc. have occupied a prominent place in the world of folk arts and literature. The tales and poems are still enjoyed by people, when presented by folk artists in Lok Dayora (a gathering where people are entertained by folk artists). Even Bhavais (street plays) are performed telling them the stories of our great epics; today these street plays are performed to awaken citizens with their rights. This folk heritage is now moving towards extinction as today our youths are drawn towards western culture and arts. There is an urgent need for preservation of dying Kathiawari art forms and literature. Special care should be taken for the upliftment of the folk artists. Keywords : Extinction, Prevention, Folk art & literature Kathiawar, officially known as Saurashtra, was named richness and life force of folk literature of Kathiawar. after the Kathi community, who ruled for long in this The rich tradition of folk literature of Kathiawar is region. Kathiawar, on the West of peninsular India lies reflected by the following couplet, which exhorts the between 20 ° 40 ′ to 23 ° 25 ′ North latitude and 69 ° 5 ′ to mother to give birth only to the Bhakt – (saints or 72 °20 ′ East longitudes. -

Weekly Verse #334

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 334: Vaishnava Jana Toh - Beautiful Gujarati Bhajan (Hymn) by Poet Narsinh Mehta – Mahatma Gandhiji’s very favorite Bhajan Hello all Tele Class friends: Seasonal Ayaathrem Gaahambaar – Meher Maah – Aastaad to Aneraan Roj Zoroastrian Society of Washington State (ZSWS) of Seattle celebrates all six Seasonal Gaahambaars and Mobedyaar Jamshid Pouresfandiary performs all Gaahambaar Jashans. They will celebrate Ayaathrem Gaahambaar during the five days – Meher Maah, Aastaad Roj through Aneraan Roj – October 12 – 16. Many other Irani and Parsi Associations also celebrate these Seasonal Gaahambaars. Narsinh Mehta: Narsinh Mehta is still a very liked and followed Gujarati poet/saint, notable as “Bhakta” – exponent of “Vaishnav” poetry. He lived during the fifteenth century. He was called “Aadi Kavi” (Sanskrit for “The First Among Poets”.). His Gujarati Bhajan – Vaishnava Jana To – was Mahatma Gandhi’s favorite and has become synonymous to him. Narsinh Mehta was born in a Nagar Brahmin family at Talaja and later moved to Junagadh in Saurashtra peninsula of modern-day Gujarat. His father held an administrative post in a royal court. He lost his parents when he was five years old. He could not speak until the age of eight. He was raised by his grandmother Jaygauri. He married Manekbai probably in the year 1429. Mehta and his wife stayed at his brother Bansidhar's house in Junagadh. However, Bansidhar's wife did not welcome Narsinh very well. She was an ill-tempered woman, always taunting and insulting Narsinh Mehta for his devotion (Bhakti). One day, when Narasinh Mehta had enough of these taunts and insults, he left the house and went to a nearby forest in search of some peace, where he fasted and meditated for seven days by a secluded Shiva lingam until Lord Shiva appeared before him in person. -

Class Notes Class: VII Topic: Ch

Class Notes Class: VII Topic: Ch . 8 . Devotional paths to the divine (Worksheet) Subject: Social Science 1. This is a picture of Baba Guru Nanak as a young man, in discussion with holy men. Answer the following questions related to Guru Nanak: a. Where was Baba Guru Nanak born? b. Who was appointed by Guru Nanak as his successor? c. When did Baba Guru Nanak die? d. Who ordered the execution of Guru Arjan and why? 2. Many people believed that their social privileges came from their higher birth in a noble family or in a higher caste. But many people did not agree with such ideas. In fact, many religions came forward with the teaching that it was possible to overcome social differences and break the cycle of rebirth through personal efforts. Who spread these new ideas? A. Kabir and the Jains B. Buddha and the Jains C. Meera bai and Narsinh Mehta D. Buddha and Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti 3. With the growth of new towns, trade, and empires between the 7th and the 17th centuries, new ideas developed and different groups of people worshipped different gods and goddesses. Muslims, for example, believed in Allah, and Christians believed in Jesus. Which idea became widely accepted during that time? A. All living things are immortal. B. All living things pass through countless cycles of birth and rebirth. C. Human beings are superior to God. D. Living things are separate from God. 4. In the 7th and 9th centuries, we saw the emergence of new religious movements led by the Nayanars and the Alvars. -

The Image of God Presented in the Devotional Poems of Narsinh Mehta

IF : 4.547 | IC Value 80.26 VolumVOLeUME-6, : 3 | Iss uISSUE-6,e : 11 | N ovembJUNE-2017er 2014 • ISSN • ISSN No N o2277 2277 - -8160 8179 Original Research Paper English Literature The Image of God Presented in the Devotional Poems of Narsinh Mehta Chintan Jayvant Ph.D. English Literature, Bhuj-Kutch, Gujarat (India) Arya ABSTRACT The medieval history of India is full of socio-political and religious upheavals that changed the straight-jacketed scenario of pre-medieval time. The spontaneous reformation that took place with the creations of Poet saints of the time brought drastic changes in the political, social and religious panorama . It mainly took its initiatives from the South Indian Movement propagated by the Alwār and Nayanār tradition of saints that advocated the Bhakti as a means to retain salvation. In Gujarāt, the systematic growth can be traced in the creations of Narsinh Mehta who is hailed as the Ādi Kavi for his earliest compositions in Gujarati. History of Gujarati Literature will always be indebted to Narsinh for his matchless creations. He presented the most complicated philosophies of Vedic Brāhminic religion in couple of lines with utmost ease and that is his mastery. He mostly propagated Premlakshanā Bhakti in his poems. In most of his poems he addressed God Krishna as his beloved and hence desperately urged for His benevolence. Unlike the earlier projection of God, he projected Krishna as a shepherd that dwelled among countryman in day to day life, taking care of their problems. Hence, he broke the conventional portrayal that was presented by the upper Sanskritized class and made Him a God of common man.