'Utmost Bliss'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sound of an Album Cover: Probabilistic Multimedia and IR

The Sound of an Album Cover: Probabilistic Multimedia and IR Eric Brochu Nando de Freitas Kejie Bao Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science University of British Columbia University of British Columbia University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC, Canada Vancouver, BC, Canada Vancouver, BC, Canada [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We present a novel, flexible, statistical approach to modeling music, images and text jointly. The technique is based on multi-modal mixture mod- els and efficient computation using online EM. The learned models can be used to browse mul- timedia databases, to query on a multimedia database using any combination of music, im- ages and text (lyrics and other contextual infor- mation), to annotate documents with music and images, and to find documents in a database sim- ilar to input text, music and/or graphics files. 1 INTRODUCTION An essential part of human psychology is the ability to Figure 1: The CD cover art for “Singles” by The Smiths. identify music, text, images or other information based on Using this image as input, our querying method returns associations provided by contextual information of differ- the songs “How Soon is Now?” and “Bigmouth Strikes ent media. Think no further than a well-chosen image on Again” – also by The Smiths – by probabilistically cluster- a book cover, which can instantly establish for the reader ing the query image, finding database images with similar the contents of the book, or how the lyrics to a familiar histograms, and returning songs associated with those im- song can instantly bring the song’s melody to mind. -

Today in the Tdn in Tdn Europe

SUNDAY, MAY 5, 2019 T O D A Y I N T H E T D N FINLEY: STEWARDS WERE RIGHT, BUT THE SYSTEM IS WRONG BRICKS AND MORTAR KEEPS STREAK GOING IN TURF CLASSIC MIA MISCHIEF GETS HER GI IN HUMANA DISTAFF MITOLE CONTINUES HIS ASCENT AT CHURCHILL DOWNS DIGITAL AGE CAPS BIG DAY FOR INVINCIBLE SPIRIT MR MONEY GETS THE CASH IN PAT DAY MILE I N T D N E U R O P E GUINEAS GLORY FOR MAGNA GRECIA SCAT DADDY DOUBLY REPRESENTED IN 1000 DE SOUSA SHINES ON COMMUNIQUE Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe/International PUBLISHER & CEO Sue Morris Finley @suefinley [email protected] V.P., INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS Gary King @garykingTDN [email protected] EDITORIAL [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Jessica Martini @JessMartiniTDN Managing Editor Sunday, May 5, 2019 Alan Carasso @EquinealTDN Senior Editor Steve Sherack @SteveSherackTDN Racing Editor Brian DiDonato @BDiDonatoTDN News and Features Editor Ben Massam @BMassamTDN Associate Editors Christie DeBernardis @CDeBernardisTDN Joe Bianca @JBiancaTDN ADVERTISING [email protected] Director of Advertising Alycia Borer Advertising Manager Lia Best Advertising Designer Amanda Crelin Advertising Assistants Alexa Reisfield Amie Morosco Advertising Assistant/Dir. Of Distribution Rachel McCaffrey Photographer/Photo Editor Sarah K. Andrew @SarahKAndrew [email protected] Country House (Lookin At Lucky) walks during a lengthy objection following Saturday’s Social Media Strategist GI Kentucky Derby. | Horsephotos Justina Severni Director of Customer Service NICODEMUS TAKES THE WESTCHESTER 21 Vicki Forbes Nicodemus became the newest graded winner for his top sire [email protected] Candy Ride (Arg) with a win in Belmont’s GIII Westchester S. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name, Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent I Broodmare 3895 dk. b./br. m. Salt Loch, 1996 Salt Lake Jolie Scot Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent II Weanling 4074 ch. c. unnamed, 2005 Van Nistelrooy Don't Answer That Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent V Broodmare 3807 dk. b./br. m. Magic in the Music, 1995 Dixieland Band Shared Magic Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent VI Broodmare 3874 b. m. Queen's Castle, 1995 Pleasant Tap Castle Eight Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent VII Weanling 3934 b. c. unnamed, 2005 Include Sweet Elyse Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent Stallion prospect 4327 gr/ro. c. Third Sacker, 2001 Maria's Mon De La Cat Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Ellie Boje Farm Broodmare 4256 b. m. Rahy's Hope, 1996 Rahy Roberto's Hope Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Kuehne Racing Broodmare 4249 dk. b./br. m. Princess Pamela, 1999 Binalong Constant Talk Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Sam-Son Farm Broodmare 4416 ch. m. Dixieland Briar, 1999 Dixieland Band Roman Briar Barn 46 Consigned by William Anderson, Agent Broodmare 4317 dk. b./br. m. Superdor, 1993 Cawdor Allerton Barn 48 Consigned by Aspendell, Agent Broodmares 4279 ch. m. Scram, 1990 Stalwart Flaxen 4303 ch. m. Spritz, 1994 Relaunch Supplier Weanlings 4280 b. c. unnamed, 2005 Ride the Rails Scram 4389 ch. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart Lyrics

Nine inch nails things falling apart lyrics click here to download NINE INCH NAILS lyrics - "Things Falling Apart" () EP, including "10 Miles High (Version)", "Metal", "Where Is Everybody? (Version)". Things Falling Apart. Nine Inch Nails. Released K. Things Falling Apart Tracklist. 1 Starfuckers, Inc. (Version - Sherwood) Lyrics. 5. Nine Inch Nails song lyrics for album Things Falling Apart. Tracks: Slipping Away, The Great Collapse, The Wretched, Starfuckers, Inc., The Frail, Starfuckers Inc., The Wretched · Starfuckers, Inc. · Starfuckers Inc. · Where Is Everybody? All lyrics for the album Things Falling Apart by Nine Inch Nails. Tracklist with lyrics of the album THINGS FALLING APART [] from Nine Inch Nails: Slipping Away - The Great Collapse - The Wretched - Starfuckers, Inc. I. Features Song Lyrics for Nine Inch Nails's Things Falling Apart album. Includes Album Cover, Release Year, and User Reviews. Lyrics Depot is your source of lyrics to Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart songs. Please check back for new Nine Inch Nails Things Falling Apart music lyrics. Slipping Away, The Great Collapse, Starfuckers, Version A, The Wretched (Version), The Frail. Nine Inch Nails - Things Falling Apart Lyrics - Full Album. Things Falling Apart is the second remix album by American industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails, released on November 21, by Nothing Records and. Nine Inch Nails - Things Falling Apart (Remix EP) - www.doorway.ru Music. Things Falling Apart, a collection of severely remixed songs from The Fragile, adds . of Discs: 1; Format: Explicit Lyrics, EP; Label: Nothing; ASIN: BZB9L. Things Falling Apart album by Nine Inch Nails. Find all Nine Inch Nails lyrics in music lyrics database. -

Stephen King * the Mist

Stephen King * The Mist I. The Coming of the Storm. This is what happened. On the night that the worst heat wave in northern New England history finally broke-the night of July 19-the entire western Maine region was lashed with the most vicious thunderstorms I have ever seen. We lived on Long Lake, and we saw the first of the storms beating its way across the water toward us just before dark. For an hour before, the air had been utterly still. The American flag that my father put up on our boathouse in 1936 lay limp against its pole. Not even its hem fluttered. The heat was like a solid thing, and it seemed as deep as sullen quarry-water. That afternoon the three of us had gone swimming, but the water was no relief unless you went out deep. Neither Steffy nor I wanted to go deep because Billy couldn't. Billy is five. We ate a cold supper at five-thirty, picking listlessly at ham sandwiches and potato salad out on the deck that faces the lake. Nobody seemed to want anything but Pepsi, which was in a steel bucket of ice cubes. After supper Billy went out back to play on his monkey bars for a while. Steff and I sat without talking much, smoking and looking across the sullen flat mirror of the lake to Harrison on the far side. A few powerboats droned back and forth. The evergreens over there looked dusty and beaten. In the west, great purple thunderheads were slowly building up, massing like an army. -

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 2

TOEJAMANDEARL - Round 2 1. The audio of the 1995 game Quest for Fame is based on works by these people. Members of the New Order Nation, including Helga, kidnap these people in a game whose projectiles include compact discs. These people are unlocked as playable characters as part of the Nipmuc High School level, which also includes a cover of Mott the Hoople’s “All the Young Dudes.” That game, which includes Tom Hamilton and all other people of this type, is the first dedicated spin-off of the Guitar Hero series. The rail shooter Revolution X stars, for 10 points, what group of musicians that includes Joe Perry and Steven Tyler? ANSWER: the members of Aerosmith 2. One activity in this game ideally requires waiting for a certain number on-screen to reach 1,484 and ignoring the player character entirely. Completing one task in this game causes a mole to appear if it’s done on the last possible attempt. A special controller for playing this game on the Atari 2600 has no joystick and just three buttons, which echoes its arcade control scheme. One object in this game can be deliberately thrown off the screen, which will kill a bird. Several activities in this game have between 42 and 45 degrees as optimal launch angles. For 10 points, name this Konami game that begins with a button-mashing 100-yard-dash. ANSWER: Track & Field 3. A trilogy of light-gun shooters whose titles start with this word center on “Rage” and “Smarty,” a pair of police officers. -

EDITED PEDIGREE for ZUMAATY (IRE)

EDITED PEDIGREE for ZUMAATY (IRE) Nayef (USA) Gulch (USA) Sire: (Bay 1998) Height of Fashion (FR) TAMAYUZ (GB) (Chesnut 2005) Al Ishq (FR) Nureyev (USA) ZUMAATY (IRE) (Chesnut 1997) Allez Les Trois (USA) (Bay gelding 2018) Danehill Dancer (IRE) Danehill (USA) Dam: (Bay 1993) Mira Adonde (USA) BLACKANGELHEART (IRE) (Bay 2006) Magical Cliche (USA) Affirmed (USA) (Bay 1994) Talking Picture (USA) 4Sx5D Northern Dancer, 5Sx5D Raise A Native ZUMAATY (IRE), placed twice at 3 years, 2021 and £2,142. 1st Dam BLACKANGELHEART (IRE), unraced; dam of 3 winners: STRAIGHT ASH (IRE) (2015 g. by Zebedee (GB)), won 5 races to 6 years, 2021 and £31,866 and placed 17 times. URLO (IRE) (2014 c. by Equiano (FR)), won 3 races in Italy at 5 years and £12,075 and placed 5 times. FLAMMENSCHLAG (IRE) (2016 c. by Footstepsinthesand (GB)), won 1 race in Russia at 2 years and placed once. Zumaaty (IRE), see above. Octola (IRE) (2019 g. by Free Eagle (IRE)), ran once on the flat at 2 years, 2021. 2nd Dam Magical Cliche (USA), placed 6 times at 3 and 4 years including third in Derrinstown Stud 1000 Guineas Trial, Leopardstown, L.; Own sister to TRUSTED PARTNER (USA), LOW KEY AFFAIR (USA), EASY TO COPY (USA) and EPICURE'S GARDEN (USA); dam of 4 winners: MAGICAL THOMAS (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed 6 times; also won 4 races over hurdles from 5 to 7 years and placed 13 times and won 2 races over jumps in Jersey at 7 years. LEGEND HAS IT (IRE), won 3 races at 3 years and placed twice; dam of winners. -

Reznor Reveals Individuality Cd Review Coolest Guys in the World

SIGNAL Tuesday. April L, Features 25 Reznor reveals individuality Cd review coolest guys in the world. add to his long list of achieve Trent Reznor, Producer He has done work on ments. He has compiled an "Lost Highway" Oliver Stone's soundtrack, re other movie soundtrack for soundtrack leased CDs of artistically epic David Lynch's movie, "Lost proportions, and sparked a Highway." By Tommy Lee (ones, III music revolution towards in Reznor changes his Staff writer dustrial music as well as in ways a bit on this soundtrack. spired artists like Poe to do The music is a little more re Trent Reznor has come a what Reznor does. fined and a little less in-the- long way from playing the He composes his music dark erratic. Reznor has spo tuba in his high school using the computer, by him ken about deviating from his marching band. Reznor was self, then hires people to per project known as Nine Inch once the dorkiest kid in form with his onstage. Nails. school. Now, he is among the Reznor has a new honor to On this soundtrack, Reznor sings several songs under lason Kay (bottom left) and fellow lamiroquai members worked his own name rather than together to release latest album. "Travelling Without Moving.' the pseudonym Nine Inch Nails. Jamiroquai does some soul Reznor's soundtrack re minds those more familiar travelling on "Moving" with classical music, of the energy and passion as well as Cd review ets in the path of smooth gui creative ingenuity which is Jamiroquai tar and bass grooves on "Vir characterized with old school "Travelling Without tual Insanity" and "You Are composers. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Breeze up Web App .Indd

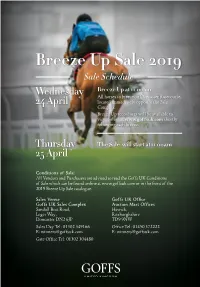

Breeze Up Sale 2019 Sale Schedule Breeze Up at 11.00am Wednesday All horses to breeze on Doncaster Racecourse, located immediately opposite the Sale 24 April Complex. Breeze Up recordings will be available to view online at www.goffsuk.com shortly following each breeze. Thursday The Sale will start at 11.00am 25 April Conditions of Sale: All Vendors and Purchasers are advised to read the Goffs UK Conditions of Sale which can be found online at www.goffsuk.com or in the front of the 2019 Breeze Up Sale catalogue. Sales Venue Goffs UK Office Goffs UK Sales Complex Auction Mart Offices Sandall Beat Road, Hawick, Leger Way, Roxburghshire DoncasterTo DN2come 6JP TD9 9NW Sales Day Tel: 01302 349166 Office Tel: 01450 372222 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Gate Office Tel: 01302 304480 1 Index To Consignors Index to Consignors Index toTo Consignors Consignors Lot Box Aguiar Bloodstock 34 f Starspangledbanner - Sister Sylvia...............................................................C165 68 f Cappella Sansevero - Zelie Martin...............................................................C166 75 c Cappella Sansevero - Almatlaie...............................................................C167 130 c Showcasing - Lady Brigid...............................................................C168 Ardglass Stables 5 c Hot Streak - Park Law...............................................................E251 11 f Declaration of War - Princess Consort...............................................................E252 Ballinahulla Stables 92 -

Arbiter, March 5 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 3-5-1997 Arbiter, March 5 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. �. I nth 2 INSIDE , - WEDNESDAY, MARCH 5, 1997THEARBITER The legislature techni- There are too many of us as it is, and who needs cally approved pay two of Jack Kevorkian or Macualay Culkin running increases for BSU around? faculty, but did not Recall the tale of a man who jolted life into a -- ... ~-"~Q.pinion appropriate new monster whose limbs were collected from various Cloning isn't a good idea. money to fund dead people, then stitched together. Frankenstein , . them. They say was the scientist, not the monster, and he was a taxes would rise man who played God. Of course, it was only a if they increased work of Mary Shelley's imagination, but the moral salaries, and all of the.story is: messing with life, attempting to the while Idaho's make it better and even creating it will backfire. '''''''''''"''S- "",'- ': '~, d~kiL~it:<,·. state employees arc Life doesn't get any better or more advanced than News working hard for less Censorship symposium compliments exhibit at humanity.