Late Iron Age Settlement Evidence from Rogaland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Library Faculty January 2013 The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W. Onsager Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Onsager, Lawrence W., "The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 25. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Faculty at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANASON FAMILY IN ROGALAND COUNTY, NORWAY AND JUNEAU COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Berrien Springs, Michigan and Mauston, Wisconsin 2013 ANASON FAMILY INTRODUCTION The Anason family has its roots in Rogaland County, in western Norway. Western Norway is the area which had the greatest emigration to the United States. The County of Rogaland, formerly named Stavanger, lies at Norway’s southwestern tip, with the North Sea washing its fjords, beaches and islands. The name Rogaland means “the land of the Ryger,” an old Germanic tribe. The Ryger tribe is believed to have settled there 2,000 years ago. The meaning of the tribal name is uncertain. Rogaland was called Rygiafylke in the Viking age. The earliest known members of the Anason family came from a region of Rogaland that has since become part of Vest-Agder County. -

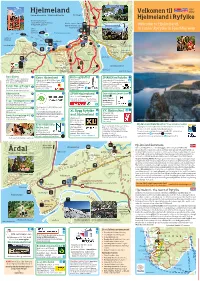

Hjelmeland 2021

Burmavegen 2021 Hjelmeland Nordbygda Velkomen til 2022 Kommunesenter / Municipal Centre Nordbygda Leite- Hjelmeland i Ryfylke Nesvik/Sand/Gullingen runden Gamle Hjelmelandsvågen Sauda/Røldal/Odda (Trolltunga) Verdas største Jærstol Haugesund/Bergen/Oslo Welcome to Hjelmeland, Bibliotek/informasjon/ Sæbø internet & turkart 1 Ombo/ in scenic Ryfylke in Fjord Norway Verdas største Jærstol Judaberg/ 25 Bygdamuseet Stavanger Våga-V Spinneriet Hjelmelandsvågen vegen 13 Sæbøvegen Judaberg/ P Stavanger Prestøyra P Hjelmen Puntsnes Sandetorjå r 8 9 e 11 s ta 4 3 g Hagalid/ Sandebukta Vågavegen a Hagalidvegen Sandbergvika 12 r 13 d 2 Skomakarnibbå 5 s Puntsnes 10 P 7 m a r k 6 a Vormedalen/ Haga- haugen Prestagarden Litle- Krofjellet Ritlandskrateret Vormedalsvegen Nasjonal turistveg Ryfylke Breidablikk hjelmen Sæbøhedlå 14 Hjelmen 15 Klungen TuntlandsvegenT 13 P Ramsbu Steinslandsvatnet Årdal/Tau/ Skule/Idrettsplass Hjelmen Sandsåsen rundt Liarneset Preikestolen Søre Puntsnes Røgelstad Røgelstadvegen KART: ELLEN JEPSON Stavanger Apal Sideri 1 Extra Hjelmeland 7 Kniv og Gaffel 10 SMAKEN av Ryfylke 13 Sæbøvegen 35, 4130 Hjelmeland Vågavegen 2, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 916 39 619 Vågavegen 44, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 454 32 941. www.apalsideri.no [email protected] Prisbelønna sider, eplemost Tlf 51 75 30 60. www.Coop.no/Extra Tlf 938 04 183. www.smakenavryfylke.no www.knivoggaffelas.no [email protected] Alt i daglegvarer – Catering – påsmurt/ Tango Hår og Terapi 2 post-i-butikk. Grocery Restaurant - Catering lunsj – selskapsmat. - Selskap. Sharing is Caring. 4130 Hjelmeland. Tlf 905 71 332 store – post office Pop up-kafé Hairdresser, beauty & personal care Hårsveisen 3 8 SPAR Hjelmeland 11 Den originale Jærstolen 14 c Sandetorjå, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 51 75 04 11. -

Sports Manager

Stavanger Svømme Club and Madla Svømmeklubb were merged into one swimming club on the 18th of April 2018. The new club, now called Stavanger Svømmeklubb, is today Norway's largest swimming club with 4000 members. The club that was first founded in 1910 has a long and proud history of strong traditions, defined values and solid economy. We are among the best clubs in Norway with participants in international championships (Olympics, World and European Championships). The club give children, youngsters, adults and people with disabilities the opportunity to learn, train, compete and develop in a safe, healthy and inclusive environment. The club has a general manager, an office administrator, a swimming school manager, 7 full-time coaches, as well as a number of group trainers and swimming instructors. The main goal for Stavanger Svømmeklubb is that we want be the preferred swimming club in Rogaland County and a swimming club where the best swimmers want to be. Norway's largest swimming club is seeking a Sports Manager Stavanger Svømmeklubb is seeking an experienced, competent and committed sports manager for a full time position that can broaden, develop and strengthen the club's position as one of the best swimming clubs in Norway. The club's sports manager will be responsible for coordinating, leading and implementing the sporting activity of the club, as well as having the professional responsibility and follow-up of the club's coaches. The sports manager should have knowledge of Norwegian swimming in terms of structure, culture and training philosophy. The job involves close cooperation with other members of the sports committee, general manager and coaches to develop the club. -

Søknad Om Utfylling I Sjø Ved 69/580, Luravika, Sandnes Kommune - Anmodning Om Uttale Til Søknaden - Utlegging Til Offentlig Ettersyn

Deres ref.: Vår dato: 05.12.2017 Vår ref.: 2017/11966 Arkivnr.: 461.5 Postadresse: Postboks 59 Sentrum, Sandnes kommune 4001 Stavanger Postboks 583 Besøksadresse: 4305 Sandnes Lagårdsveien 44, Stavanger T: 51 56 87 00 F: 51 52 03 00 E: [email protected] www.fylkesmannen.no/rogaland Sandnes kommune - Søknad om utfylling i sjø ved 69/580, Luravika, Sandnes kommune - Anmodning om uttale til søknaden - Utlegging til offentlig ettersyn Fylkesmannen ber om opplysninger om spesielle forhold m.v. som bør tas hensyn til ved behandling av søknaden. Vi ber om at søknadsdokumentene og et eksemplar av kunngjøringen blir lagt ut til offentlig ettersyn i kommunen. Frist for kommunens uttalelse er satt til 8 uker. Fylkesmannen i Rogaland har mottatt søknad fra Sandnes kommune om tillatelse etter forurensningsloven § 11, jf. § 16. Søknaden gjelder utfylling i sjø i forbindelse med tilrettelegging for badeplass. Kort redegjørelse av omsøkte tiltak: Type virksomhet: arbeider i sjø Søknaden gjelder: utfylling i sjø Plassering: gnr. 69, bnr. 580, nordre ende Luravika Utfyllingsmasse volum: ca. 360 m3 Beregnet berørt areal: ca. 1100 m2 Brukstid: mars-mai (tentativ) Planlagte avbøtende tiltak: søker har foreslått bruk av tildekkingsduk under utfyllingsarbeidene Det omsøkte tiltaksområdet er avsatt til badeplass/-område i reguleringsplan. Det skal være litt stabilitetsutfordringer i området grunnet en kombinasjon av bløte sedimenter og topografiske forhold. Bane Nor SF er grunneier av det omsøkte tiltaksområdet. Bakgrunn/Søknad Sandnes kommune planlegger/undersøker mulighetene for å tilrettelegge for en offentlig bynær badeplass i nordre ende av Luravika. En del av tilretteleggingen går ut på å lage et større oppholdsareal på land. -

Verdiar I Høievassdraget, Tysvær Kommune I Rogaland

Verdiar i Høievassdraget, Tysvær kommune i Rogaland VVV-rapport2000- 4 , P," f a _; v f; C k _ f fi___ fl' 1"?,,,l _»5 f ‘A?: t —:'::——;—,;5,;;=i;2,1,," "—.:":=é:'—""' ' a f ,/ / å? ,/ j '/. _/ -v\\.‘ r.,- .f \. ."""/‘~\ J,‘ .N,../. .”og _\ZJ,,- x.LN _ U i. A \___ u.) f . , \ -'>__. .\ \/7»; `L Nr f i: , e s-\__[_,_cw Rf.. 4,-. \_. ;"\ f' ` (K \- \ i r "l Z Utgitt av Direktoratet for naturforvaltning i samarbeid med Noregsvassdrags- og energidirektorat, Tysvær kommune og Fylkesmannen i Rogaland Refererast som: Tysvær kommune og Fylkesmannen iRogaland 2000. Verdiar iHøievassdraget, Tysvær kommune i Rogaland. Utgitt av Direktoratet for naturforvaltning i samarbeid med Noregs vassdrag- og energidirektorat. VVV-rapport 2000-4. Trondheim 42 sider, 4 kart+vedlegg. Forside foto: ”Utmark på Hoiestølen”, John Morten Klingstøl, Tysvær kommune Forside layout: Knut Kringstad Verdiar i Hoievassdraget, Tysvær kommune i Rogaland Vassdragsnr.: 039.71 Verneobjekt: 039/1 Verneplan IV VVV-rapport 2000-4 Rapport utarbeidaav Tysværkommunei samarbeidmedFylkesmanneniRogaland Tittel Dato Antall sider Verdiar iHøievassdraget Kunnskapsstatus pr. oktober 1998 42 s., 4 kart + vedlegg Forfattar Institusjon Ansvarlig sign John Morten Klingsheim Tysvær kommune/Fylkesmannen iRogaland Per Terje Haaland TE-nr. ISSN-nr ISBN-nr. VVV-Rapport nr. 882 1501-4851 82-7072-389-4 2000-4 Vassdragsnavn Vassdragsnummer Fylke Høievassdraget (Haugevassdraget) 039. 71 Rogaland Vernet vassdrag nr Antall objekter/omr Kommune 039/1 14 Tysvær Antall delområder med Nasjonal verdi (***) Regional verdi (**) Lokal verdi(*) Potensiell verdi (-) 1 0 2 ll EKSTRAKT Høievassdraget i Tysvær kommune i Rogaland er vema vassdrag nr 039/ 1 i vemeplan for vassdrag IV (utgjer kring en tredel av eininga 039.71 i Regineregistret). -

Vann I Stavanger 2018‐2029 ______

Vann i Stavanger 2018‐2029 ____________________________________________________ Hovedplan for vannforsyning, avløp, vannmiljø og overvann HØRINGSUTKAST Oktober 2018 1 HØRINGSUTKAST SEPTEMBER 2018 DETTE PLANDIKUMENTET ER HØRINGSUTKASTET AV «VANN I STAVANGER 2018‐2029». ETTER HØRINGEN VIL PLANEN BLI JUSTERT OG TILPASSET VEDTAK OG INNSPILL. VIDERE VIL PLANEN BLI OPPARBEIDET GRAFISK FØR ANDREGANGSBEHANDLING I KOMMUNALSTYRET OG ENDELIG VEDTAK I BYSTYRET. 2 Innhold Planens hovedgrep (sammendrag) ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1 Innledning ....................................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Visjoner og verdier .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Overordnede planer ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 1.3 Generelle fokusområder ................................................................................................................................................ 10 1.4 Benchmarking ................................................................................................................................................................ 11 1.5 Status for gjennomføring av -

Rapport Om Økonomisk Status I Bymiljøpakken 17.11.20 (002)

1234zxcv./ subheadline: 13/16 Arial Bold. Innholdsfortegnelse 1. Oppsummering 3 2. Innledning 6 2.1 Bakgrunn for PwCs undersøkelse 6 2.2 PwCs mandat 6 2.3 PwCs team 7 2.4 Metodisk tilnærming 7 2.5 Forbehold 7 3. Økonomisk status 8 3.1 Innledning 8 3.2 Økonomisk status i Nord-Jærenpakken per 1. juli 2017 8 3.2.1 Innledning 8 3.2.2. Kostnader i prosjektene fra 1998-2002 9 3.2.3 Kostnader i prosjektene fra 2003 - 30. juni 2017 11 3.2.4 Totale kostnader fra 1998 - 30. juni 2017 11 3.2.5 Våre funn sammenholdt med avsluttende regnskap 13 3.2.6 Inntekter i Nord-Jærenpakken per 1. juli 2017 15 3.2.7 Status per 1. juli 2017 for Nord-Jærenpakken 16 3.3 Kostnader i prosjekter overført fra Nord-Jærenpakken 16 3.3.1 Overførte prosjekter 16 3.3.2 Utgifter i prosjektene fra 1. juli 2017 til 31. august 2020 18 3.3.3 Kostnader etter 31. august 2020 og prognoser i ikke-avsluttede prosjekter 19 3.4 Finansiering av prosjekter overført fra Nord-Jærenpakken fra 1. juli 2017 til 30. september 2018 22 4. Netto økonomisk bidrag til Bymiljøpakken 24 5. Dagens økonomiske status sammenlignet med Finansieringsplan datert 22. mars 2017 25 5.1 Finansieringsplan av 22. mars 2017 25 5.2 Avvik fra finansieringsplanen 26 5.2.1 Lavere bompengeinntekter 26 2 Økonomisk status etter overføring av prosjekter fra Nord-Jærenpakken til Bymiljøpakken 5.2.2 Økte kostnader i prosjektene 27 5.2.3 Økt antall prosjekter 27 5.2.4 Gjeld til bilister 27 5.2.5 Belønningsmidler 28 5.2.6 Konklusjon 28 6. -

Water Chemistry and Acidification Recovery in Rogaland County

INNSENDTE ARTIKLER Water chemistry and acidification recovery in Rogaland County By Espen Enge Espen Enge is senior engineer, Environmental Division, County Governor of Rogaland. Sammendrag Introduction Redusert forsuring av fjellvann i Rogaland Due to exceptionally slow weathering bedrock, fylke. Her bearbeides resultater fra i alt 1144 the concentrations of ions in river and lake water prøver fra 2002, 2007 og 2012. Tre ulike forsurings in the mountain areas of southern Norway are modeller antydet at forsuringen i fjellområdene i generally very low (Wright and Henriksen 1978). Rogaland (>500 m) i dag er begrenset, og at In Rogaland, 12% of the surveyed lakes in 1974 vannkvaliteten trolig er nær en opprinnelig ufor 1979 (Sevaldrud and Muniz 1980) had conduc suret vannkvalitet. Mange lavereliggende inn tivity of <10 µS/cm, and the minimum value was sjøer var tilsynelatende fortsatt forsuret, men 4.2 µS/cm. disse estimatene kan være forbundet med usik Dilute, weakly buffered water is highly sensi kerhet. Ioneinnholdet i vannet i fjellområdene er tive to acidification. Thus, as early as the 1870s ekstremt lavt, noe som i seg selv trolig utgjør en the brown trout population (Salmo trutta) in begrensning for utbredelsen av aure. Sandvatn in Hunnedalsheiene declined close to extinction (HuitfeldtKaas 1922), possibly due to Summary emerging acidification (Qvenild et al. 2007). In The current study compiles data from 1144 water the 1920s massive fish kills due to acidic water samples from three large regional water chemical were observed in the salmon rivers Dirdal, Fra surveys, performed in 2002, 2007 and 2012. fjord and Espedal (HuitfeldtKaas 1922). -

Prosjekt: Reg.Plan Bussveien Fv.44 Gausel Stasjon - Hans Og Grete Stien

ENDRINGSNOTAT Prosjekt: Reg.plan Bussveien fv.44 Gausel stasjon - Hans og Grete stien Sandnes kommune, plan nr 2009-119 Stavanger kommune, plan nr 2299 Region vest Stavanger kontorstad 23.12.2016 Innledning Endringer som er gjort i planen siden offentlig ettersyn fremgår av dette endringsnotatet til regulerings- planen. Kommunenes tilleggspunkt i vedtak for 1.gangsbehandling (før offentlig ettersyn) er kommentert på side 3 i dette endringsnotatet. Merknader mottatt i forbindelse med offentlig ettersyn og begrensede høringer, er sammenfattet og kommentert i et eget hefte for merknadsbehandling. Forslag til reguleringsplan for fv. 44 Gausel stasjon – Hans og Grete stien, datert 19.06.2015 lå ute til offentlig ettersyn i perioden 30.11.2015 – 22.01.2016 i Sandnes kommune og 09.10. – 20.11.2015 i Stavanger kommune. Det kom inn merknader fra 30 ulike offentlige og private interesser. Etter høringsperioden ble planen endret noe som følge av mottatte merknader. Noen av disse endringene ble grunnlag for ny begrenset høring. Etter den begrensede høringsrunden kom det inn merknader fra 15 ulike offentlige og private interesser. Vedtak i kommunene I forbindelse med kommunenes vedtak om utlegging til offentlig ettersyn, ble det i tillegg fattet følgende vedtak: Sandnes kommune, Utvalg for byutvikling, møte 04.11.2015 sak 94/15 1. Senest før 2. gangsbehandling skal det vurderes løsninger for å unngå redusert framkommelighet for syklister gjennom lysregulerte rundkjøringer med bussprioritering. 2. Utvalg for byutvikling ber om å få fremlagt en løsning med undergang i området for foreslått bro ved Midtbergmyra. Undergangen bør være lys og bred med rampe som går i plan med fortau med videre tilkomst direkte til Hans og Grete stien. -

Jwc Community Support

JWC COMMUNITY SUPPORT WELCOME TO NORWAY GUIDE http://www.jwc.nato.int/ JWC Community Support Updated Dec 13 1 INDEX Page NORWAY – GENERAL 3 HISTORY OF THE HEADQUARTERS 4 FORWORD BY CHIEF COMMUNITY SUPPORT SECTION 5 COMMUNITY SUPPORT SECTION 6 HOUSING 7 ITEMS TO BRING WITH YOU 7 SCHOOLING 9 FINANCES 10 MEDICAL AND DENTAL 11 EMERGENCY TELEPHONE NUMBERS 12 WELFARE AND RECREATION 13 TRANSPORT AND THE CAR 15 CUSTOMS REGULATIONS 21 SHOPPING FACILITIES 23 USEFUL WEBSITES 24 2 NORWAY - GENERAL GEOGRAPHY The Norwegian coastline is 21,000 km long with hundreds of fjords and inlets. It is a rugged, mountainous country with limited rail and road communications when away from the main centres of population. Much of the coastal area is best serviced by ship and much of the coastal road between Stavanger and Trondheim is only accessible by means of tunnel and ferry. (The city of Bergen is some 125 road miles north of Stavanger but will take up to 6 hours and approximately 600 NOK to reach). Air travel is becoming increasingly important and is the only really practical method of covering the large distances between the major cities unless you have time on your hands - Oslo is some 8 hours away by road (12 hours in the winter snow). Norway, with an area of 386,958 sq. km has a population of around 4.5 million, much of who are located in the southern part of the country where you will live and work. TROMSO BODO ARCTIC CIRCLE TRONDHEIM BERGEN STAVANGER OSLO Stavanger is situated on the Southwestern coast of Norway (in the county of Rogaland), some 600km from Oslo, the capital of Norway, and lies on a line of latitude level with the northern Orkney Islands. -

Kommunestyre- Og Fylkestingsvalget 2019

Kommunestyre- og fylkestingsvalget 2019 Valglister med kandidater Kommunestyrevalget 2019 i Stavanger Valglistens navn: Høyre Status: Godkjent av valgstyret Kandidatnr. Navn Fodselsar Bosted Stilling 1 John Peter Hernes 1959 Madla 2 Sissel Knutsen Hegdal 1965 Madla 3 Nina Ørnes 1996 Hundvag 4 Egil Olsen 1956 Hundvag 5 Nils Petter Flesjå 1974 Finnøy 6 Frank-Arild Normanseth 1962 Rennesøy 7 Karl Stefan Afradi 1990 Madla 8 Bjørg Ager-Hanssen 1932 Hillevåg 9 Morten Landråk Asbjørnsen 1993 Hinna 10 Linda Nilsen Ask 1964 Rennesøy 11 Hard Olav Bastiansen 1955 Eiganes og Våland 12 Knut Oluf Hoftun Bergesen 1983 Storhaug 13 Else Karin Bjørheim 1998 Tasta 14 Tone Knappen Brandtzæg 1946 Storhaug 15 Henrik Bruvik 2000 Hinna 16 Jarl Endre Egeland 1971 Hundvåg 17 Terje Eide 1968 Eiganes og Våland 18 Stine Marie Emilsen 1967 Eiganes og Våland 19 Narve Eiliv Endresen 1964 Tasta 20 Ingebjørg Storeide Folgerø 1960 Eiganes og Våland 21 Helge Gabrielsen 1951 Hundvåg 22 Kjell Erik Grosfjeld 1972 Hinna 23 Bente Gudmestad 1965 Rennesøy 24 Andres Svadberg Hatløy 1964 Madla 25 Andreas Helgøy 1998 Hundvag 26 lne Johannessen Helvik 1975 Hinna 27 Hilde Hesby 1984 Tasta 28 Jonas Molde Hollund 2001 Tasta 29 Berit Marie Hopland 1946 Finnøy 30 Noor Mohamed Mohamed Hussain 1944 Hillevåg 31 Sara Hønsi 2001 Madla 32 Kristen Høyer Mathiassen 1962 Madla 23.05.2019 13:01.25 Lister og kandidater Side 15 Kommunestyre- og fylkestingsvalget 2019 Valglister med kandidater Kommunestyrevalget 2019 i Stavanger Valglistens navn: Høyre Status: Godkjent av valgstyret Kandidatnr. Navn -

EIGANES/VÅLAND for KIDS N INKL

LuftetureEIGANES/VÅLAND FOR KIDS n INKL. SANDAL, STOKKA, KAMPEN & BJERGSTED www.lufteturen.no KOM AN! BYDELSGUIDE: LEK, TURER OG AKTIVITETER 1 UT PÅ TUR LEV LIVET LOKALT! Livet i barnefamilien handler gjerne om de små, nære ting. Dette heftet byr på hverdagens muligheter til tur, trim og trivsel i ditt nærområde. Stavanger byr på mange gode lufteturer sammen med ungene. I det grønne, i det urbane, i gatene, i næringsområder eller steder med kulturell og historisk betydning. En halvtime her og en time der ute av hus er gull verdt for humør og helse. Hver lille tur skaper et nytt univers – i hvert fall for ungene. Bli med dem, på deres nivå, og få felles opplevelser og innsikter. Hvor mange bein har egentlig et skrukketroll? Er det hasselnøtter i krattet nedi svingen? Utforsk det sammen! Det handler om kontakt – med hverandre og med omgivelsene. De små tingene er egentlig store. Vår venn Viggo Voff vil ha folk ut på nærtur – med ungene som guider. Dette heftet skal være deres. Lufteturen viser frem noen av tingene dere kan gjøre under åpen himmel i by- delen. Sjekk hverdagsturene lenger bak i heftet – det er ikke noe krav å gå hele turen. Det er spennende å jakte på røde T-er! Prøv en ny lekeplass eller et nytt friområde – det finnes fortsatt uoppdagede kontinenter innenfor bydelens grenser. Les mer på www.lufteturen.no og på www.facebook.com/Lufteturen. Bli en lufteturist i din egen flotte bydel! Hilsen Viggo Voff og resten av Luftetur-gjengen Hvor mange plasser kan Produsert med støtte fra Stavanger kommune du finne Viggo Voff i brosjyren? Riktig svar helt bakerst.