Georgia Department of Natural Resources Meet with Students Who Had Chosen This Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comodo System Cleaner Version 3.0

Comodo System Cleaner Version 3.0 User Guide Version 3.0.122010 Versi Comodo Security Solutions 525 Washington Blvd. Jersey City, NJ 07310 Comodo System Cleaner - User Guide Table of Contents 1.Comodo System-Cleaner - Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 1.1.System Requirements...........................................................................................................................................5 1.2.Installing Comodo System-Cleaner........................................................................................................................5 1.3.Starting Comodo System-Cleaner..........................................................................................................................9 1.4.The Main Interface...............................................................................................................................................9 1.5.The Summary Area.............................................................................................................................................11 1.6.Understanding Profiles.......................................................................................................................................12 2.Registry Cleaner............................................................................................................................................. 15 2.1.Clean.................................................................................................................................................................16 -

SA4VBE08KN/12 Philips MP4 Player with Fullsound™

Philips GoGEAR MP4 player with FullSound™ Vibe 8GB* SA4VBE08KN Feel the vibes of sensational sound Small, colorful and entertaining The colored Philips GoGEAR Vibe MP4 player SA4VBE08KN comes with FullSound to bring music and videos to life, and Songbird to synchronize music and enjoy entertainment. SafeSound protects your ears and FastCharge offers quick charging. Superb quality sound • Fullsound™ to bring your MP3 music to life • SafeSound for maximum music enjoyment without hearing damage Complements your life • 4.6 cm/1.8" full color screen for easy, intuitive browsing • Soft and smooth finish for easy comfort and handling • Enjoy up to 20 hours of music or 4 hours of video playback Easy and intuitive • Philips Songbird: one simple program to discover, play, sync • LikeMusic for playlists of songs that sound great together • Quick 5-minute charge for 90 minutes of play • Folder view to organize and view media files like on your PC MP4 player with FullSound™ SA4VBE08KN/12 Vibe 8GB* Highlights FullSound™ level or allow SafeSound to automatically Philips Songbird regulate the volume for you – no need to fiddle with any settings. In addition, SafeSound provides daily and weekly overviews of your sound exposure so you can take better charge of your hearing health. 4.6 cm/1.8" full color screen Philips' innovative FullSound technology One simple, easy-to-use program that comes faithfully restores sonic details to compressed with your GoGear player, Philips Songbird lets MP3 music, dramatically enriching and you discover and play all your media, and sync enhancing it, so you can experience CD music it seamlessly with your Philips GoGear. -

Special Characters A

453 Index ■ ~/Library/Safari/WebpageIcons.db file, Special Characters 112 $(pwd) command, 89–90 ~/Library/Saved Searches directory, 105 $PWD variable, 90 ~/Library/Services directory, 422–423 % (Execute As AppleScript) menu option, ~/Library/Workflow/Applications/Folder 379 Actions folder, 424 ~/ directory, 6, 231 ~/Library/Workflows/Applications/Image ~/bin directory, 6, 64, 291 Capture folder, 426 ~/Documents directory, 281, 290 ~/Movies directory, 323, 348 ~/Documents/Knox directory, 255 ~/Music directory, 108, 323 ~/Downloads option, 221, 225 ~/Music/Automatically Add To iTunes ~/Downloads/Convert For iPhone folder, folder, 424 423–424 ~/Pictures directory, 281 ~/Downloads/MacUpdate ~/.s3conf directory, 291 Desktop/MacUpdate Desktop ~/ted directory, 231 2010-02-20 directory, 16 ~/Templates directory, 60 ~/Downloads/To Read folder, 425 ~/Templates folder, 62 ~/Dropbox directory, 278–282 Torrent program, 236 ~/Library folder, 28 1Password, 31, 135, 239–250 ~/Library/Application 1Password extension button, 247–248 Support/Evom/ffmpeg directory, 1Password.agilekeychain file, 249 338 1PasswordAnywhere tool, 249 ~/Library/Application 1Password.html file, 250 Support/Fluid/SSB/[Your 2D Black option, 52 SSB]/Userstyles/ directory, 190 2D With Transparency Effect option, 52 ~/Library/Application Support/TypeIt4Me/ 2-dimensional, Dock, 52 directory, 376 7digital Music Store extension, 332 ~/Library/Caches/com.apple.Safari/Webp age Previews directory, 115 ~/Library/Internet Plug-Ins directory, 137 ■A ~/Library/LaunchAgents directory, 429, 432 -

Proceedings High Altitude Revegetation Workshop No. 16 March 2004 Edited by Warren R. Keammerer and Jeffrey Todd Information

Proceedings High Altitude Revegetation Workshop No. 16 March 2004 Edited by Warren R. Keammerer and Jeffrey Todd Information Series No. 99 Proceedings HIGH ALTITUDE REVEGETATION WORKSHOP NO. 16 Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado March 3-5, 2004 Edited by Warren R. Keammerer 5858 Woodbourne Hollow Road Keammerer Ecological Consultants, Inc., Boulder, CO and Jeffrey Todd Todd Consulting Service 14338 W. 58th Place Arvada, CO Information Series No. XX Colorado Water Resources Research Institute Colorado State University Printed Copies Available From: Cooperative Extension Resource Center General Services Center Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 Phone: 970/491-6308 FAX: 970/491-2961 PREFACE The 16th biannual High Altitude Revegetation Conference was held at the University Park Holiday Inn, Ft. Collins, Colorado on March 3-5, 2004. The Conference was organized by the High Altitude Revegetation Committee in conjunction with the Colorado State University Department of Soil and Crop Science. The Conference was attended by 207 people from a broad spectrum of universities, government agencies and private companies. It is always encouraging to have participants from such a wide range of interests in and application needs for reclamation information and technology. Organizing a two-day workshop and field trip is a difficult task made relatively easy by the sharing of responsibilities among the members of the HAR Committee. In addition to the invited papers and poster papers presented on March 3-4, a “field tour” of the Hydraulics Laboratory on the Foothills Campus of Colorado State University was conducted on March 5, 2004. We appreciate and thank the organizers of the field tour. -

Here.Is.Only.Xul

Who am I? Alex Olszewski Elucidar Software Co-founder Lead Developer What this presentation is about? I was personally assigned to see how XUL and the Mozilla way measured up to RIA application development standards. This presentation will share my journey and ideas and hopefully open your minds to using these concepts for application development. RIA and what it means Different to many “Web Applications” that have features and functions of “Desktop” applications Easy install (generally requires only application install) or one-time extra(plug in) Updates automatically through network connections Keeps UI state on desktop and application state on server Runs in a browser or known “Sandbox” environment but has ability to access native OS calls to mimic desktop applications Designers can use asynchronous communication to make applications more responsive RIA and what it means(continued) Success of RIA application will ultimately be measured by how will it can match user’s needs, their way of thinking, and their behaviour. To review RIA applications take advantage of the “best” of both web and desktop apps. Sources: http://www.keynote.com/docs/whitepapers/RichInternet_5.pdf http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rich_Internet_application My First Steps • Find working examples Known Mozilla Applications Firefox Thunderbird Standalone Applications Songbird Joost Komodo FindthatFont Prism (formerly webrunner) http://labs.mozilla.com/featured- projects/#prism XulMine-demo app http://benjamin.smedbergs.us/XULRunner/ Mozilla -

BBLC: Technology Edition Resources 02/01/2008

BBLC: Technology Edition Resources 02/01/2008 General Vanderbilt software: http://its.vanderbilt.edu/software/personal/ Educational discount software: http://www.journeyed.com/jump.exe?EF695 VU free antivirus software: http://its.vanderbilt.edu/antivirus/downloads.php Cellular discounts: http://its.vanderbilt.edu/cellphone/ VUSpace (online storage): http://its.vanderbilt.edu/vuspace/ VUSpace (personal website): http://its.vanderbilt.edu/help/vuspace/vuspace.htm VU sponsored music options: http://www.vanderbilt.edu/vumix/ Office 2007 Ultimate discount (good until 4/3/08): http://www.theultimatesteal.com/ Backup Automatic online ($$) Mozy: http://mozy.com/ Carbonite: http://www.carbonite.com/ Offline: Syncback: http://www.2brightsparks.com/downloads.html SuperDuper: http://www.shirt-pocket.com/SuperDuper/SuperDuperDescription.html Calendaring, todos, PIMs Online Google Calendars: http://www.google.com/calendar MS Live: http://calendar.live.com stikkit: http://stikkit.com/ Remember the Milk: http://www.rememberthemilk.com/ Offline Spicebird: http://www.spicebird.com/ ThinkingRock: http://www.thinkingrock.com.au/ DoIt http://www.jimmcgowan.net/Site/DoIt.html Actiontastic: http://www.kaboomerang.com/blog/actiontastic-faq/ iGTD: http://bargiel.home.pl/iGTD/ OmniFocus ($$): http://www.omnigroup.com/applications/omnifocus/ J.Ma Email VU email configuration: http://its.vanderbilt.edu/vumail/configure.php Free Clients Eudora: http://www.eudora.com/ Thunderbird: http://www.mozilla.com/en-US/thunderbird/ Endnote and references Peabody Library workshops: -

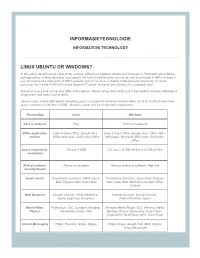

Informasietegnologie Linux Ubuntu Or Windows?

POST LIST INFORMASIETEGNOLOGIE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LINUX UBUNTU OR WINDOWS? In this article we will look at a few of the common differences between Ubuntu and windows 8. Firstly with any software package before making decisions most people will look at what it would cost me as user to purchase it. With windows 8 you are looking at a retail price of R800 upwards, but of course as a student of Stellenbosch University, it can be purchased for a mere R180-00 from the Student IT Centre. However with Ubuntu, it’s completely free! Now let’s have a look at how they differ at first glance, Ubuntu brings their Unity look to the platform whereas Windows 8 brings there new metro look to theirs. Ubuntu is also a fairly light weight operating system compared to Windows 8 which takes up 16 to 20 GB of hard drive space compared to Ubuntu’s 4.5GB. Below is a table of a list of relevant comparisons. Feature/App Linux Windows Cost to end-user Free R800 and upwards Office application Libre & Open Office, Google docs, Libre & Open Office, Google docs, Office 365 + choices Office Web Apps, Soft maker Office Web Apps, Microsoft Office suite, Soft maker Office Space required for OS size 4.5GB OS size is 16 GB (32-bit) or 20 GB (64-bit) installation Risk of software Almost non existent Various malicious software, High risk security threats Email clients Thunderbird, Evolution, KMail, Opera Thunderbird, Evolution, Opera Mail, Pegasus Mail, Pegasus Mail, Claws Mail Mail, Claws Mail, Windows Live Mail, Office Outlook Web Browsers Google Chrome, Firefox/Waterfox, -

DVD-Libre 2007-12 DVD-Libre Diciembre De 2007 De Diciembre

(continuación) Java Runtime Environment 6 update 3 - Java Software Development Kit 6 update 3 - JClic 0.1.2.2 - jEdit 4.2 - JkDefrag 3.32 - jMemorize 1.2.3 - Joomla! 1.0.13 - Juice Receiver 2.2 - K-Meleon 1.1.3 - Kana no quiz 1.9 - KDiff3 0.9.92 - KeePass 1.04 Catalán - KeePass 1.09 - KeePass 1.09 Castellano - KeyJnote 0.10.1 - KeyNote 1.6.5 - Kicad 2007.07.09 - Kitsune 2.0 - Kompozer 0.7.10 - Kompozer 0.7.10 Castellano - KVIrc 3.2.0 - Launchy 1.25 - Lazarus 0.9.24 - LenMus 3.6 - Liberation Fonts 2007.08.03 - lightTPD 1.4.18-1 - Lilypond 2.10.33-1 - Linux DVD-Libre Libertine 2.6.9 - LockNote 1.0.4 - Logisim 2.1.6 - LPSolve IDE 5.5.0.5 - Lynx 2.8.6 rel2 - LyX 1.5.2-1 - LyX 1.5.2-1 cdlibre.org Bundle - Macanova 5.05 R3 - MALTED 2.5 - Mambo 4.6.2 - Maxima 5.13.0 - MD5summer 1.2.0.05 - Media Player Classic 6.4.9.0 Windows 9X / Windows XP - MediaCoder 0.6.0.3996 - MediaInfo 0.7.5.6 - MediaPortal 0.2.3.0 - 2007-12 MediaWiki 1.11.0 - Memorize Words Flashcard System 2.1.1.0 - Mercurial 0.9.5 - Minimum Profit 5.0.0 - Miranda IM 0.7.3 Windows 9X / Windows XP - Miro 1.0 - Mixere 1.1.00 - Mixxx 1.5.0.1 - mod_python 3.3.1 (py 2.4 - ap 2.0 / py 2.4 - ap 2.2 / py 2.5 - ap 2.0 / py 2.5 - ap 2.2) - Mono 1.2.4 - MonoCalendar 0.7.2 - monotone 0.38 - Moodle DVD-Libre es una recopilación de programas libres para Windows. -

Da Archive Annex June 10Th 2018 New Links Will Be Placed Here for a While Before Adding Them to Da Archive

Da Archive Annex June 10th 2018 New links will be placed here for a while before adding them to Da Archive. PLEASE BUY A COPY OF THE BOOKS THAT YOU USE If you can't understand why you should support your game, go work at Burger King for 2 weeks for no pay and you might get a clue. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Sorry for the incomplete links and L33t gibberish. This way seems to be a good idea, what with all the matrixbots and cyber crotchspiders out there. SS, $$, or @SS is sendspace, m3g4 is mega, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. There is a u$ercl0ud and a u$er$cl0ud, be careful to go to the correct one. $n!p<dot>li, s00<dot>gd, and h1v3<dot>@m links are cAsE sEnSeTiVe Anon Has Pointed Out That A Few Sites Used Have Unwanted Clutter That Can Be Annoying. “Be warned the site it's on is rife with malware traps. When you figure it out make sure the file you're saving is a .PDF and not the same thing with .EXE stuck on the end. The second one is a million bad programs that eat your compooter like I eat Cheetos.” Special thanks to Da Archivist, Mageguru, Here!, Agent13, TheWiz!, The Warden, Fat Charley, Blink_Dog, DiosMios, Porthos, The Greyhawk Ranger, Fitz-Empress bani Flambeau, helpful, CityofCarse, donkey, Magister Man, ABF, 3DoorsDownDude, Smink, Nergal, Okultek, JaZZ, UglyPanda, VL All the Awesome Curators, and the entire Anon Brigade. Extra Special thanks to the Pioneers who paved the way. -

Time Structures Chronomes in and Around Us Halberg

Franz Halberg, Sergei M. Chibisov, Ivan V. Radysh, Germaine Cornélissen, Andrej A. Bakulin TIME STRUCTURES (CHRONOMES) IN US AND AROUND US Moscow – 2005 1 ББК 28.073 У т в е р ж д е н о Х 17 РИС Ученого совета Российского университета дружбы народов E d i t e d b y professor V.A. Frolov Medical Faculty, People's Friendship University of Russia, Moscow Halberg F., Chibisov S.M., Radysh I.V., Cornélissen G., Bakulin A.A. TIME STRUCTURES (CHRONOMES) IN US AND AROUND US: Monography. – Moscow: PFUR, 2005. – 186 p. In this the book the problems of chronobiology, chrono- cardiology, and chronoastrobiology in light of modern representa- tions about mechanisms regulation of biological rhythms are shined. ISBN 5-209-00747-2 ББК 28.073 © Halberg F., Chibisov S.M., Radysh I.V., Cornélissen G., Bakulin A.A., 2005 © Publishing house: People's Friendship University of Russia, 2005 2 CONTENTS Introduction ……………………………………….... 4 Chronobiology …………………………………….. 12 Chronoastrobiology ………………………………... 53 Conclusion ………………………………………… 143 References ………………………………………… 151 3 INTRODUCTION Structures in time are called chronomes; their mapping in us and around us is called chronomics. The scientific study of chronomes is chronobiology. And the scientific study of all as- pects of biology related to the cosmos has been called astrobiol- ogy. Hence we may dub the new study of time structures in biol- ogy with regard to influences from cosmo- helio-and geomag- netic rhythms chronoastrobiology. It has, of course, been understood for centuries that the movements of the earth in relation to the sun produce seasonal and daily cycles in light energy and that these have had profound effects on the evolution of life. -

User Manual Contents 6 Update the Firmware Through Philips Songbird 15

Register your product and get support at GoGEAR www.philips.com/welcome SA4DOT02 SA4DOT04 SA4DOT08 User manual Contents 6 Update the firmware through Philips Songbird 15 1 Important safety information 4 7 Repair the player through Philips General maintenance 4 Songbird 16 Recycling the product 6 8 Technical data 17 2 Your new player 7 PC requirements 17 What's in the box 7 PC software for the player 7 Files loaded on the player 7 Overview 7 Controls 7 LED indicator and audio feedback 8 3 Get started 9 Charge power 9 Switch the player on or off 9 Automatic standby and shut-down 9 4 Play music 10 Transfer music to the player 10 Play music 10 Search for a song 10 Change the volume level 10 Switch the random play on or off 10 5 Sync with PC music library through Philips Songbird 11 Install Philips Songbird on your PC 11 Collect music files from the PC 11 Set the watch folder 11 Import music files 13 Sync the player with Philips Songbird 13 Select auto or manual sync 13 Auto sync 13 Manual sync 14 Need help? Please visit www.philips.com/welcome where you can access a full set of supporting materials such as user manual, the latest software updates and answers to frequently asked questions. EN 3 Replacement parts/accessories: 1 Important safety Visit www.philips.com/support to order replacement parts/accessories. information Hearing Safety General maintenance At full power, the prolonged listening of the walkman can damage the ear of the user. -

Freiesmagazin Jahresindex 2006-2016

INDEX freiesMagazin-Index 2006-2016 3 Android (Fortsetzung) 3D-Desktop Rezension: Spieleprogrammierung mit Android Studio 10/2014 Compiz nun doch als Standard in Gutsy Gibbon 10/2007 Compiz und Beryl vereinigen sich wieder 05/2007 KWin 4.2 – Neues aus dem Land der wabernden Fenster 02/2009 Anleitungen Multipointer-Unterstützung im X-Server 08/2008 Beschleunigung von Updates 06/2006 Einrichten von alias 07/2006 A Grundwissen: isos brennen 04/2006 Afrika Intelligente Befehlshistory-Suche 06/2006 Freie Software – Eine Chance für Afrika? 08/2007 Musik-Empfehlungs-Services 08/2006 Interview mit Alex Antener 08/2007 Paketmedien erstellen 07/2006 linux4afrika – Entwicklungshilfe der anderen Art 09/2007 Podcasts 06/2006 Sichere Passwörter für Webseiten 09/2006 Android Android Google-frei konfigurieren und Alternativen einrichten 04/2015 Anwendungen Freie Software im Bereich Android 12/2016 amaroK 1.4 veröffentlicht 06/2006 Rezension: Android 3 – Apps entwickeln mit dem Android 11/2011 Automatix – so wird Ubuntu einfach 06/2006 SDK Ding – das Offline-Wörterbuch 12/2010 Rezension: Android 4 – Apps entwickeln mit dem Android 10/2012 F-Spot – Ersatz für gthumb 10/2006 SDK Google Reader 11/2006 Rezension: Android – Apps entwickeln 09/2012 Google-Earth jetzt auch für Linux 07/2006 Rezension: Android – Einstieg in die Programmierung 09/2014 Graphische Einstellung des XServers 08/2006 Rezension: Android – kurz & gut 02/2014 HOW-TO: Backups – wie, wann, womit 05/2006 Rezension: Android-Apps entwickeln 02/2012 Netzwerk-Monitoring: Ethereal und KSniffer 12/2006