Andrew Wilson April 17, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romeo+Juliet

DEAR EDUCATOR: What could be better than teaching Romeo and Juliet, perhaps the greatest love story of + all time? And this year, to enrich ROMEO JULIET your students’ engagement, THE MOST DANGEROUS LOVE STORY EVER TOLD. you can include the newest film adaptation of Shakespeare’s TARGET AUDIENCE For Part 2, Have students do some research to find adaptations or classic in your class plans. High school and college courses in English references to Romeo and Juliet in popular culture. These can be Literature, Shakespeare, and Creative Writing. either contemporary or historic examples. Ask them to prepare Revitalized for a whole new short presentations on what they find, generation by Academy Award®- PROGRAM OBJECTIVES encouraging them to think about historical winning screenwriter Julian • To identify major themes in Romeo and Juliet and geographical context (when was my Fellowes and acclaimed director and explore their continued relevance today. example created? where was it created?) as Carlo Carlei, this telling of • To analyze various examples of how Romeo well as audience (who was it created for? ROMEO & JULIET takes viewers and Juliet has been adapted or updated in what types of people would best understand popular culture. and appreciate it?) to draw conclusions about back to the enchanting world why this particular popular twist on Romeo of the story’s original setting in • To enhance students’ skills for moving easily between Shakespeare’s English and the way and Juliet was effective—or not! Verona, Italy. Douglas Booth and ® we speak today. Academy Award Nominee Hailee • To engage students’ creativity, using music to enrich their ACTIVITY TWO Steinfeld lead an extraordinary understanding of tone, emotion, and meaning across key scenes SHAKESPEARE IN OUR TIMES ensemble cast who bring in Romeo and Juliet. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo Da Vinci) Tom Has Been Seen in A

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo da Vinci) Tom has been seen in a variety of TV roles, recently portraying Dr. Laurence Shepherd opposite James Nesbitt and Sarah Parish in ITV1’s critically acclaimed six-part medical drama series “Monroe.” Tom has completed filming the highly anticipated second season which premiered autumn 2012. In 2010, Tom played the role of Gavin Sorensen in the ITV thriller “Bouquet of Barbed Wire,” and was also cast in the role of Mr. Wickham in the ITV four-part series “Lost in Austen,” alongside Hugh Bonneville and Gemma Arterton. Other television appearances include his roles in Agatha Christie’s “Poirot: Appointment with Death” as Raymond Boynton, as Philip Horton in “Inspector Lewis: And the Moonbeams Kiss the Sea” and as Dr. James Walton in an episode of the BBC series “Casualty 1906,” a role that he later reprised in “Casualty 1907.” Among his film credits, Tom played the leading roles of Freddie Butler in the Irish film Happy Ever Afters, and the role of Joe Clarke in Stephen Surjik’s British Comedy, I Want Candy. Tom has also been seen as Romeo in St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold alongside Colin Firth and Rupert Everett and as the lead role in Santiago Amigorena’s A Few Days in September. Tom’s significant theater experiences originate from numerous productions at the Royal Court Theatre, including “Paradise Regained,” “The Vertical Hour,” “Posh,” “Censorship,” “Victory,” “The Entertainer” and “The Woman Before.” Tom has also appeared on stage in the Donmar Warehouse theatre’s production of “A House Not Meant to Stand” and in the Riverside Studios’ 2010 production of “Hurts Given and Received” by Howard Barker, for which Tom received outstanding reviews and a nomination for best performance in the new Off West End Theatre Awards. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

The Limehouse Golem’ by

PRODUCTION NOTES Running Time: 108mins 1 THE CAST John Kildare ................................................................................................................................................ Bill Nighy Lizzie Cree .............................................................................................................................................. Olivia Cooke Dan Leno ............................................................................................................................................ Douglas Booth George Flood ......................................................................................................................................... Daniel Mays John Cree .................................................................................................................................................... Sam Reid Aveline Mortimer ............................................................................................................................. Maria Valverde Karl Marx ......................................................................................................................................... Henry Goodman Augustus Rowley ...................................................................................................................................... Paul Ritter George Gissing ................................................................................................................................ Morgan Watkins Inspector Roberts ............................................................................................................................... -

Martin Phipps

MARTIN PHIPPS COMPOSER Coming from a musical background (he is Benjamin Britten’s godson), Martin read drama at Manchester University and fortunately for the acting profession, he decided to concentrate his energies on writing music. Since scoring his first TV drama, Eureka Street in 2002, he has won 2 BAFTAs, 5 Ivor Novello Awards and received multiple Emmy nominations for writing music to many of the most interesting series of recent years. These include the BBC’s War and PeaCe, Hugo Blick’s The Honourable Woman, Peaky Blinders, Black Mirror and season 3 & 4 of the Leftbank Pictures/Netflix series The Crown. Martin’s film credits include Woman In Gold (scored with Hans Zimmer), starring Ryan Reynolds and Helen Mirren, Fox Searchlight’s The Aftermath, starring Keira Knightley and Alexander Skarsgård, Harry Brown and Brighton Rock. Martin set up Mearl, a project to facilitate collaborations with other artists and composers, as well as a platform for developing his own material. Peaky Blinders was the first soundtrack written under this name, scored with a band of musicians from Radiohead’s new Laundry Studios in London Fields. FEATURE FILM THE AFTERMATH Fox Searchlight Pictures Director: James Kent Producers: Ridley Scott, Jack Arbuthnott, Malte Grunert Starring: Keira Knightley, Alexander Skarsgård WOMAN IN GOLD Origin Pictures / Weinstein Company Director: Simon Curtis Producer: Harvey Weinstein, Kris Thykier, David M Thompson, Christine Langan, Ed Rubin Starring: Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds, Jonathan Pryce, Katie Holmes, Charles Dance, -

Refugee Week Resource for Schools

REFUGEE WEEK 14th – 20th June 2021 RESOURCES FOR SCHOOLS ALL KEY STAGES Daily Prayer for Refugee Week Our grateful thanks go to Lizzie Sowerby and the pupils of St Winifred’s RC Primary School, Stockport, for creating content for a different daily prayer slide during Refugee Week. The daily prayer will be posted on our social media platforms at 8am each morning for you to use in school and share with your wider community. Facebook: Caritas Diocese of Salford Twitter: @CaritasSalford Instagram: caritas_salford Learning Resources Refugee Week is coming, and there all kinds of ways children and young people can take part, 14 – 20 June. We’re delighted to share with you the new Refugee Week Children + Young People’s Pack for 2021, full of ideas and resources to help young people of all ages understand what it means to be a refugee, and inspire them to help build a more welcoming world. The resources are produced by a range of different organisations and include films, books, learning packs and creative activities. For teachers – whether you’re looking for a short activity, lesson plan, material for assemblies or inspiration for an ongoing project, we hope you’ll find something to suit your classroom. For families – pick an activity to explore with children at home, or share the pack with their school and invite them to take part in Refugee Week. Thousands of young people take part in Refugee Week every year – and it wouldn’t happen without you. Thank you! https://refugeeweek.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Children-Young-Peoples-Pack- Refugee-Week- -

Introduction to Social Media | Building an Online Advocacy Campaign Page No. 1 / 32

Building an online advocacy campaign Page No. 1 / 32 Social Media 1 - Introduction to Social Media | Building an online advocacy campaign In this resource, we will show how social media can be used to advocate for social change, through a case study of the UNHCR’s online advocacy work. Page No. 2 / 32 Social Media 1 - Introduction to Social Media | Building an online advocacy campaign What is advocacy? Advocacy is any action that speaks in favor of, recommends, or argues for a cause, or that supports, defends, or pleads on behalf of others. Advocacy means actively supporting a cause and trying to get others to support it as well. It is an effective tool to change practices and policies. SORRY FOR THE INCONVENIENCE Who can be an WE ARE TRYING advocate? TO CHANGE THE Anyone who cares about the cause can be an advocate, as can WORLD anyone who was mobilized by a campaign. The main goal of any advocacy campaign is to raise awareness about its cause. Following that a campaign will ask people to contribute: to donate, volunteer, or spread the word, etc. Advocates use their voices to share ideas, persuade people to believe in an issue, and join them in creating change. Advocates are the first candidates to be volunteers. Page No. 3 / 32 Social Media 1 - Introduction to Social Media | Building an online advocacy campaign Examples of advocacy campaigns Advocacy takes many forms. It can be about raising awareness about an issue (like education for girls), or mobilizing people around a cause (such as fighting domestic violence). -

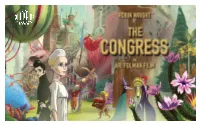

Robin Wright

02 SYNOPSIS Robin Wright, playing the role of herself, gets an offer from a major studio to sell her cinematic identity: she‘ll be numerically scanned and sampled so that her alias can be used with no restrictions in all kinds of Hollywood films – even the most commercial ones that she previously refused. In exchange she receives loads of money, but more importantly, the studio agrees to keep her digitalized character forever young – for all eternity – in all of their films. The contract is valid for 20 years. The Congress follows Robin as she makes her comeback after the contract expires, straight into the world of future fantasy cinema. 03 04 Into the psychochemical whirlwind foreseen tribulations after selling her image, up until the by Lem, the film adaptation of his novel intro- moment when the studio turns her into a duces the current cinematic technologies of chemical formula. 3-D and motion capture, which threaten to eradicate the cinema we grew up on. In the Only the mesmerizing combination of anima- post-“Avatar” era, every filmmaker must pon- tion – with the beautiful freedom it bestows der whether the flesh and blood actors who on cinematic interpretation – and quasi- have rocked our imagination since childhood documentary live-action, can illustrate the can be replaced by computer-generated 3-D transition made by the human mind between images. Can these computerized characters psychochemical influence and deceptive create in us the same excitement and ent- reality. The Congress is primarily a futuristic husiasm, and does it truly matter? The film, fantasy, but it is also a cry for help and a entitled The Congress, takes 3-D computer profound cry of nostalgia for the old-time images one step further, developing them into cinema we know and love. -

Romeo and Juliet Wider Reading Booklet

Romeo and Juliet Wider Reading Booklet An introduction to Shakespearean Tragedy Daughters in Shakespeare: dreams, duty and defiance Character analysis: Romeo and Juliet in Act 2, Scene 2 – Part 1 Character analysis: Romeo and Juliet in Act 2, Scene 2 – Part 2 The violence of Romeo and Juliet Juliet's eloquence Romeo + Juliet at 20: Baz Luhrmann's adaptation refuses to age Key moments from Romeo and Juliet All extracts taken from the British Library, Guardian and RSC websites https://www.bl.uk/works/macbeth https://www.theguardian.com/uk https://www.rsc.org.uk/ 1 Extracts from An introduction to Shakespearean Tragedy Source: https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/an-introduction-to-shakespearean-tragedy So what is it that stamps a play as the kind of tragedy that merits the term ‘Shakespearean’? The key point should become clear if we turn to one of Shakespeare’s earliest tragedies, Romeo and Juliet. Shakespeare’s immortal couple have become a global byword for lovers driven unjustly to their doom because they belong to warring factions that refuse to tolerate their love. During the last four centuries the play has inspired countless adaptations and offshoots on stage and screen, as well as operas, symphonies, fiction, poetry and paintings. But Romeo and Juliet couldn’t have acquired its enduring resonance, if the significance and value of the tragedy were trapped in the time when Shakespeare wrote it. If the play made sense and mattered only in terms of that time, it wouldn’t be able to reach across the centuries and speak with such urgency to so many different cultures now. -

Who Was William Shakespeare?

HAILEE STEINFELD DOUGLAS BOOTH © ATOM 2013 A STUDY GUIDE BY FIONA HALL http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-388-5 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Overview He is impetuous and emotional, ruled by his heart. She is a thoughtful ingénue, new to romance. They are madly in love. Their families – bitter enemies – would disapprove if they knew. His name is Romeo and hers is Juliet. Their passion must stay shrouded in secrecy and they must sneak and scheme to find a way to be together against the odds of their families’ ancient grudge and fate itself. Sometime between 1591 and 1595, William Shakespeare wrote what would become one of his most celebrated and beloved plays – Romeo and Juliet. This tragic tale of ‘a pair of star-cross’d lovers’ has captured the hearts and imaginations of audiences ever since. For me, Romeo and Juliet is an exploration interested in bantering with her nurse than listening of what it is to be in love for the first time. to her parents. It is a timeless story, and it has never been equalled in any language. Producer Ileen At the ball, Romeo forgets his feelings for Rosaline Maisel and I wanted to give the modern when he instantly falls for Juliet. She is likewise audience a traditional, romantic version affected when she first sees Romeo. They dance of the story, complete with medieval briefly and steal a few moments alone but Romeo costumes, balconies, and duels, but we cannot stay long. Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt, has also wanted to make it immediate and noticed his presence and begs Lord Capulet to let him avenge the insult, but to no avail. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1782 GB Adults Fieldwork: 12th - 13th October 2014 Gender Age Social Grade Region Rest of Midlands / Total Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland South Wales Weighted Sample 1782 864 918 212 451 609 510 1016 766 228 579 381 438 155 Unweighted Sample 1782 831 951 68 373 731 610 1238 544 288 561 344 386 203 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following actors have you heard of? Daniel Radcliffe 87 84 90 80 87 91 85 90 83 86 91 83 86 88 Benedict Cumberbatch 77 77 78 70 74 81 79 84 69 78 82 75 74 77 James McAvoy 65 63 67 58 69 73 55 68 62 66 64 60 66 79 Robert Pattinson 59 52 66 77 72 62 36 62 55 63 56 62 57 65 Henry Cavill 24 24 23 30 31 25 13 26 21 29 24 23 22 27 Andrew Garfield 23 22 24 40 27 23 11 23 23 30 24 19 21 25 Chiwetel Ejiofor 23 23 23 17 21 27 23 27 18 34 23 23 19 18 Ben Whishaw 21 22 20 16 19 24 21 24 16 27 22 21 17 17 Nicholas Hoult 20 16 23 36 27 20 6 22 16 30 18 18 17 22 Eddie Redmayne 17 15 20 17 14 18 19 22 11 24 18 15 15 14 Jamie Dornan 13 8 17 24 17 11 5 14 11 20 13 11 8 16 Dan Stevens 13 11 15 10 8 15 16 14 11 17 13 12 12 13 Kit Harington 9 10 8 17 16 7 3 10 8 15 7 8 8 14 Douglas Booth 6 5 8 13 7 6 3 6 7 7 6 8 5 8 None of them 5 6 5 2 5 5 8 4 8 5 5 6 7 3 Don't know 3 4 1 10 4 1 0 2 3 5 1 4 3 2 and which of the following actors do you rate highly? [Asked to respondents who named an Actor; n=1665] Benedict Cumberbatch 52 54 50 51 50 52 54 55 48 52 56 49 51 46 James McAvoy 35 34 36 37 38 40 25 35 34 38 31 34 32 51 Daniel Radcliffe 30 25 34 30 30 32 26 29