Fhwa-Tx-Eis-2013-03-D Us 181

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sam Houston State Bearkats 2020 Baseball Preseason Prospectus

SAM HOUSTON STATE BEARKATS 2020 BASEBALL PRESEASON PROSPECTUS 7 SOUTHLAND CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS | 12 NCAa REGIONALS | 1 SUPER REGIONAL | 64 MLB DRAFT PICKS Bearkat quick facts 2020 SChedule GENERAL INFORMATION COACHING STAFF FEBRUARY Location ......................................................................Huntsville, Texas Head Coach .....................................................Jay Sirianni (1st season) 14 SAINT MARY’S 6:30 p.m. Founded ........................................................................................1879 Alma Mater ..............................................................Nebraska, 2001 15 SAINT MARY’S 3:00 p.m. Enrollment .................................................................................20,477 School Record ......................................................... 0-0 (1st season) 16 SAINT MARY’S 12:00 p.m. 18 RICE 6:30 p.m. Nickname ................................................................................Bearkats Career Record ...........................................................................Same 21 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT 6:30 p.m. Colors ...........................................................................Orange & White Assistant Coach (Recruiting Coord) .................Fuller Smith (1st season) 22 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT 3:00 p.m. Affiliation ......................................................................NCAA Division I Alma Mater ................................................................Ole Miss, 2008 23 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT 1:00 p.m. Conference ...........................................................................Southland -

Daily Growl Game Wrap 08

Daily Growl G A M E W R A P & P R E V I E W S O F C O M I N G A T T R A C T I O N S Monday, August 12 H O D G E T O W N A M A R I L L O , T X Amarillo Sod Poodles 2 RockHounds 2 Rocky’s Game suspended, mid-6 Corner The Cowardly Lion Said It Nicely When the Wicked Witch of the West blocked the path of Dorothy & Company to Oz by putting them to sleep in a fi eld of poppies, the Good Witch (Glinda) woke them up with some unexpected snowfall. Upon awakening, the Cowardly Lion yawned and (in that terrifi c voice) said “Peculiar weather we’re havin’, ain’t it?” This may be the fi rst time in recorded history that the words “Cowardly Lion” and “Sod Poodle” have been mentioned in the same sentence, but we had some pretty “peculiar” weather in Amarillo Monday, too. Much to the surprise of pretty much everyone … including weather forecasters (!) … Monday night’s game between the RockHounds and Sod Poodles was suspended due to rain in the middle of the sixth inning at A Statewide Road Trip... Hodgetown in Amarillo. The RockHounds took a 2-0 lead in the second on doubles from Tyler Ramirez and Taylor Motter and RBI singles A Playoff Race ... and from Greg Deichmann and Mickey McDonald. One more time around Matt Milburn tossed four scoreless innings … backed by excellent defense, including three double plays … before at Rocky Town! the Sod Poodles evened the game in the fi fth on three singles and a throwing error by fi rst baseman Chase Cala- buig. -

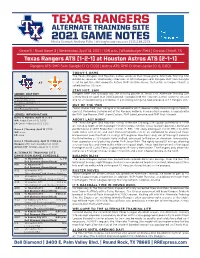

TEXAS RANGERS ALTERNATE TRAINING SITE 2021 GAME NOTES Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213

TEXAS RANGERS ALTERNATE TRAINING SITE 2021 GAME NOTES Media Contact: Andrew Felts | [email protected] | 512.238.2213 Game 5 | Road Game 3 | Wednesday, April 14, 2021 | 1:05 p.m. | Whataburger Field | Corpus Christi, TX Texas Rangers ATS (1-2-1) at Houston Astros ATS (2-1-1) Rangers ATS: RHP Sam Gaviglio (1-0, 0.00) | Astros ATS: RHP Cristian Javier (0-0, 0.00) TODAY’S GAME The Texas Rangers and Houston Astros wrap up their three-game Alternate Training Site exhibition series on Wednesday afternoon at Whataburger Field. Rangers RHP Sam Gaviglio AT is set to get the start opposite Astros RHP Cristian Javier. First pitch in Corpus Christi is scheduled for 1:05 p.m. STAY HOT, SAM SERIES HISTORY Rangers RHP Sam Gaviglio was the winning pitcher in Texas’ first Alternate Training Site Overall: 1-2-1 victory back on April 8 at Dell Diamond. Gaviglio held the Houston Astros scoreless on just In Round Rock: 1-1 one hit while recording a strikeout in 2.0 strong innings to help preserve a 4-1 Rangers win. In Corpus Christi: 0-1-1 Streak: T1 OUT OF THE ‘PEN One-Run Games: 0-0 Texas starter RHP Sam Gaviglio is scheduled to pitch approximately four innings in today’s contest. Following Gaviglio out of the Rangers bullpen, in no particular order, is expected to SERIES INFORMATION be RHP Joe Barlow, RHP Jharel Cotton, RHP Jake Lemoine and RHP Nick Vincent. Game 1 | Monday, April 12 | L 9-3 WP: Ralph Garza (1-0, 0.00) ABOUT LAST NIGHT LP: Drew Anderson (0-1, 3.00) The Texas Rangers and Houston Astros Alternate Training Site squads battled to a 1-1 tie on Tuesday night at Whataburger Field in Corpus Christi. -

Evaluates and Plans for the Transportation Needs of the Nueces and San Patricio County Areas

CSJ 0101-06-095 Affected Environment 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 LAND USE 3.1.1 History and Development Trends Permanent settlement in the area that would eventually become Corpus Christi began in the 1840s when Henry L. Kinney and William P. Aubrey established a trading post on the west shore of what is now called Corpus Christi Bay. In 1846, Corpus Christi became the county seat of newly formed Nueces County, and by the 1850s the city was laid out with numbered streets. After the Civil War, the city emerged as an important shipping center when the main ship channel was dredged to accommodate large steam ships. The first railroad arrived in 1875, with three more rail lines following by 1914 (Long 2012a). Mayor Roy Miller adopted an aggressive modernization program in 1913. In three years, the City had paved 12 miles of existing streets, constructed two miles of new streets, laid 26 miles of sanitary and storm sewers, built a garbage incinerator, and installed a new water system (WPA 1942, 169). Though travelers crossing Nueces Bay had utilized a raised oyster reef between the Nueces and Corpus Christi Bays since the 1840s, a reinforced concrete causeway was completed in 1915 (Givens and Moloney 2011, 11; 195). A hurricane in 1919 destroyed much of North Beach and the downtown area. The city was rebuilt quickly, and in 1926 a deep water port was opened to accommodate large vessels, ushering in a period of growth and prosperity for the area. The following year, a bascule bridge (drawbridge) was constructed over the Inner Harbor and opened to the traveling public. -

Whataburger 2021 Press

PRESS KIT 2021 A simple goal: to serve a burger OUR STORY so big it took two hands to hold On Aug. 8, 1950, an adventurous and determined entrepreneur named Harmon Dobson opened up the world’s first Whataburger on Ayers Street in Corpus Christi, Texas. He had a simple goal: to serve a burger so big it took two hands to hold and so good that with one bite customers would say, “What a burger!” He succeeded on both counts and turned that one little burger stand into a legend loved throughout Texas and the South. Today, each and every Whataburger is made to order, right when it’s ordered, never frozen. And they’re still made with 100 percent pure beef and served on a big toasted five-inch bun with all “the extras” to suit your taste. Grilled jalapeños, extra bacon, three slices of cheese, no tomatoes, extra pickles? No problem. Your Whataburger will be made just like you like it, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Whataburger’s following has grown exponentially in its 70-year history, thanks to a number of features, including its famous burgers and growing list of menu items; its iconic orange-and-white-striped A-Frame restaurants established in the early 1960s; its Fancy Ketchup that even has its own Facebook fan page; and its on-screen presence in every- thing from “King of the Hill” to “Friday Night Lights.” Whataburger is more than a burger chain. It is a place that feels like home to more than 50,000 employees, called Family Members, and millions of customers. -

2009 UTSA Roadrunners Baseball Media Guide

2009 UTSA Roadrunners Baseball Media Guide Quick Facts Table of Contents General Introduction Institution ___________ The University of Texas at San Antonio Media information ____________________________________ 2 Nickname __________________________________ Roadrunners goUTSA.com _________________________________________ 3 Colors ______________ Orange (1665), navy blue (289) & white 2009 season outlook _________________________________ 4-6 Founded __________________________________________ 1969 2009 schedule ________________________________________ 7 Enrollment _______________________________________28,534 2009 rosters ________________________________________ 8-9 President ______________________________Dr. Ricardo Romo Roadrunner Field ____________________________________ 10 Athletics Director ___________________________ Lynn Hickey Wolff Stadium _______________________________________ 11 Athletics phone __________________________ 210/458-4161 Ticket & camp information ____________________________ 12 Ticket office phone _______________________ 210/458-8872 Affiliation ______________________________ NCAA Division I Meet The Roadrunners Conference ___________________________________ Southland Returnee bios _____________________________________ 14-29 Coaching Staff Newcomer bios ___________________________________ 30-32 Head coach _______________ Sherman Corbett (ninth season) UTSA Baseball award winners _________________________ 33 Record at UTSA (seasons) ________________ 250-213 (eight) Head Coach Sherman Corbett ______________________ -

IWA, John Paul II Track Athletes Earn State Spots in TAPPS 5A Meet Game Jackpots / Top Prizes

2B Saturday, April 29, 2017 Caller-Times Sports on TV, radio Hooks Report ON TELEVISION rero, FS1/Fox Deportes Ten Network Club Leon, Univision/Univision Deportes THURSDAY'S BOX SCORE SATURDAY’S LISTINGS 10 p.m. — Ramon Alvarez vs. Omar Chavez, 2 p.m. — College: Texas A&M at Kentucky, 6:50 p.m. — Liga MX: Tigres UANL vs. Club Auto Racing beIN2 SEC Network Tijuana, GALA HOOKS TODAY 7 a.m. — Formula 1: Russian Grand Prix, Football 2 p.m. — College: Indiana at Michigan, Big 7 p.m. — Liga MX: CF Pachuca vs. Cruz Opponent: Frisco RoughRiders HOOKS 4, ROCKHOUNDS 3, 12 INN. Qualifying, CNBC/Univision Deportes 11 a.m. — 2017 NFL Draft, Rounds 4-7, ESPN/ Ten Network Azul, NBCU Midland AB R H BI BB SO Avg. 8 a.m. — NASCAR Monster Energy Cup Se- NFL Network 2 p.m. — College: Oklahoma State at Baylor, 7 p.m. — Portugal: Benfica vs. Estoril, When: 7:05 p.m. Saturday Vertigan lf 523110.348 ries: Toyota Owners 400, Practice, FS1 Noon — College: Arkansas Spring Game, FSSW GolTV Where: Whataburger Field Schrock 2b 600001.212 9 a.m. — NASCAR XFINITY: ToyotaCare 250, SEC Network 2 p.m. — College: San Diego at BYU, BYUtv 8:50 p.m. — Liga MX: America vs. Atlas, Pitching probables: TBA (CC) Sportman cf 502002.329 Qualifying, FS1 1 p.m. — College: Oregon Spring Game, Pac 5 p.m. — College: Grand Canyon at New Univision Deportes Rosa 1b 411312.176 10:30 a.m. — NASCAR Monster Energy Cup 12 Network Mexico State, FSSW/FCS-Pacific 9 p.m. -

2018 FRISCO ROUGHRIDERS MEDIA GUIDE Designed, Written and Laid out by Ryan Rouillard

table of contents CLUB INFORMATION club history & records Front office directory .................................. 4-5 Year-by-year records ......................................46 Ownership &and executive bios ............... 6-8 Year-by-year statistics ...................................47 Club information ..............................................9 RoughRiders timeline ..............................48-55 Dr Pepper Ballpark ...................................10-11 Single-game team records ...........................56 Texas League All-Star Games in Frisco .......12 Single-game individual records ..................57 Broadcasters, broadcast partners ...............13 Single-season team batting records ..........58 Media information and policies ..................14 Single-season team pitching records .........59 Rangers Minor League info ....................15-17 Single-season individual batting records ......60 Single-season individual pitching records ....61 COACHES & STAFF Career batting records ..................................62 Joe Mikulik (manager) .............................20-21 Career pitching records ................................63 Greg Hibbard (pitching coach) ....................22 Notable streaks...............................................64 Jason Hart (hitting coach) ............................23 Perfect games and no-hitters ......................65 Support staff, coaching awards ...................24 Opening Day lineups .....................................66 Midseason All-Stars, Futures Game ............67 -

Houston Baptist

SAM HOUSTON STATE BEARKATS 2020 BASEBALL GAME NOTES 7 SOUTHLAND CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS | 12 NCAa REGIONALS | 1 SUPER REGIONAL | 64 MLB DRAFT PICKS GAMES 12-14 • HUNTSVILLE • DON SANDERS STADIUM 2020 SChedule FEBRUARY (6-3) 14 SAINT MARY’S W, 4-0 SAM HOUSTON STATE BEARKATS 15 SAINT MARY’S W, 2-0 (6-5, 0-0 SOUTHLAND) | Head Coach: Jay Sirianni (Nebraska, 2001) 16 SAINT MARY’S L, 8-7 (11) RPI: 127 | Perfect Game: NR | Baseball America: NR | D1Baseball: NR | USA Today: NR 21 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT W, 14-6 Career Record: 6-5 (1st season) | Record at SHSU: Same 22 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT W, 5-3 23 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT W, 12-4 25 at Texas L, 4-1 28 at Louisiana W, 5-4 (11) HOUSTON BAPTIST HUSKIES 29 at Louisiana L, 1-0 (3-10, 0-0 SOUTHLAND) | Head Coach: Jared Moon (Houston Baptist, 1995) RPI: 289 | Perfect Game: NR | Baseball America: NR | D1Baseball: NR | USA Today: NR MARCH (0-2) 1 at Louisiana L, 7-5 Career Record: 384-412-2 (15th season) | Record at HBU: Same 3 LOUISIANA TECH L, 9-3 (10) 6 HOUSTON BAPTIST* 6:30 p.m. 7 HOUSTON BAPTIST* 3:00 p.m. PLAYERS TO WATCH 8 HOUSTON BAPTIST* 1:00 p.m. TRENT TOUCHET LANCE LUSK 13 at Incarnate Word* 6:30 p.m. Touchet has been a pleasant sur- Lusk has quickly turned into one 14 at Incarnate Word* 6:30 p.m. prise for the Kats at the plate this of the Kats’ go-to arms out of the 15 at Incarnate Word* 1:00 p.m. -

2010 Schedule/Results Lamar (30-22, 15-15) Vs

12 NCAA Regional Appearances * 11 Conference Championships * 2007 & 2008 SLC East Division Champions Baseball SID: Rush Wood * Office Phone: (409) 880-7845 * Cell: (409) 659-8531 * E-mail: [email protected] 2010 Schedule/Results Lamar (30-22, 15-15) vs. Stephen F. Austin (32-17, 18-11) F 19 Maine W 4-2 F 20 Maine W 6-1 Thursday, May 20, 6:30 p.m.; Friday, F 20 Maine W 5-4 (17 inns.) May 21, 6:3- p.m.; Saturday, May 22, 1 p.m. F 24 at No. 9 Rice W 13-7 Beaumont, Texas * Vincent-Beck Stadium (3,500) F 27 North Dakota State W 9-7 Radio: KLVI 560 AM (Thursday, Friday games only) F 27 North Dakota State L 9-10 F 28 North Dakota State W 12-5 Jockeying for Position Cardinals hold a commanding 44-7 advantage M 5 Dallas Baptist W 7-3 With a berth in the 2010 Southland Confer - in the series that began with a 4-0 home win in M 6 Penn State W 4-0 ence Tournament already secured, the Cardinals 1979. Lamar won three of four games from the McNeese State L 9-12 will go into this weekend’s regular-season-clos - Lumberjacks the next season and went on to win M 7 Penn State W 8-3 ing series against Stephen F. Austin jockeying 23 in a row in the series until the Jacks finally notched an 11-9 victory in Nacogdoches in 1987. M 9 Prairie View A&M W 16-1 for their final seeding position. -

GRAND OPENING TAMU-CC Raises Its Profile Across Town with the Public Dedication of New Islanders Pavilion and Courts

SPRING 2019 theIslander GRAND OPENING TAMU-CC raises its profile across town with the public dedication of new Islanders Pavilion and Courts NEW CAMPUS LEADERSHIP ATHLETICS TESTING DRONES WITH NASA Collaborative effort brings bold See 20 years of growth for TAMU-CC is one of two test sites selected to visions to life Islanders Athletics test drones in urban areas PAGE 19: Islanders break in the new pavilion at The Water's Edge park in downtown Corpus Christi. PRESIDENT'S LETTER The year following my inauguration flew by quickly; I built my leadership team and we began shaping our plans for Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. In this issue of The Islander magazine, we provide a glimpse of those plans along with a look back at our proud history. We welcomed our first freshman class 25 years ago and Islanders Athletics is celebrating its 20th anniversary. The Carnegie Commission for Higher Education recently named us an R2 Doctoral-High Research Activity campus for the first time, which demonstrates that our efforts are being recognized. These achievements and initiatives increase our impact in the community as well as in the lives of our students. I am so proud of this University and everyone here who strives for excellence every day, including our students, faculty, and staff. We also highlight the successes of some of our alumni in this issue along with amazing work being done by students and faculty. I hope you enjoy catching up on our news, and I look forward to sharing more achievements with you soon. We would love to have you come back to campus to Justin Bustos, 2018 Student visit with us in person! Government Association President, Sincerely, with Dr. -

2019 Media Guide

table of contents CLUB INFORMATION club history & records Front office directory .................................. 4-5 Year-by-year records ......................................30 Ownership/executive bios.......................... 6-8 Year-by-year statistics ...................................31 Club information ..............................................9 RoughRiders timeline ..............................32-37 Dr Pepper Ballpark ...................................10-11 Single-game team records ...........................38 Rangers affiliates............................................12 Single-game individual records ..................39 Single-season team batting records ..........40 COACHES & STAFF Single-season team pitching records .........41 Joe Mikulik (manager) .............................14-15 Single-season individual batting records ......42 Greg Hibbard (pitching coach) ....................16 Single-season individual pitching records ....43 Jason Hart (hitting coach) ............................17 Career batting records ..................................44 Support staff, coaching awards ...................18 Career pitching records ................................45 Notable streaks...............................................46 texas league & OPPONENTS Perfect games and no-hitters ......................47 Texas League info, rules and umpires ........20 Opening Day lineups .....................................48 2018 Texas League standings ......................21 Midseason All-Stars, Futures Game ............49 Amarillo