Wader Population Censuses in the Arctic: Getting the Timing Right HANS MELTOFTE1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age-Related Differences in Ruddy Turnstone Foraging and Aggressive Behavior

AGE-RELATED DIFFERENCES IN RUDDY TURNSTONE FORAGING AND AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR SARAH GROVES ABSTRACT.--Theforaging behavior of fall migrant Ruddy Turnstoneswas studiedon the Mas- sachusettscoast on 2 different substrates,barnacle-covered rocks and sand and weed-litteredflats. Foragingrates differedsignificantly between the 2 substrates.On eachsubstrate the foragingand successrates of adults and juveniles differed significantly while the frequenciesof successwere similarfor both age-classes.The observeddifferences in foragingrates of adultsand juvenilesmay be due to the degreeof refinementof foragingtechniques. Experience in searchingfor and handling prey may be a primary factor accountingfor thesedifferences, and foragingperformance probably improves with age and experience.Alternatively, the differencesmay be due to the presenceof inefficient juveniles that do not survive to adulthood. Both adultsand juveniles in the tall-depressedposture were dominant in aggressiveinteractions much morefrequently than birds in the tall-levelposture. In mixedflocks of foragingadult and juvenile turnstones,the four possibletypes of aggressiveinteractions occurred nonrandomly. Adult over juvenile interactionsoccurred more frequently than expected,and juvenile over adult interac- tions were never seen.A tentative explanationof this phenomenonmay be that juveniles misinter- pret or respondambivalently to messagesconveyed behaviorally by adultsand thusbecome espe- cially vulnerableto aggressionby adults.The transiencyof migrantsmade it unfeasibleto evaluate -

The First Record of Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius Hiaticula) in British Columbia

The First Record of Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin. Submitted: April 15, 2019. Introduction and Distribution The Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) is a widespread Old World shorebird species that is found breeding in the Arctic and subarctic regions from Greenland, Europe, east to Siberia (O’Brien et al. 2006). In North America, this species breeds on Baffin Island, eastern Ellesmere Island (Godfrey 1986). The Common Ringed Plover winters primarily from Western Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, throughout Africa, including Madagascar, and the Middle East (Hayman et al. 1986, O’Brien et al. 2006, Brazil 2009). There are three recognized subspecies of the Common Ringed Plover (Thies et al. 2018). Distinction between the subspecies is based on moult; with features changing clinally North to South, rather than East to West, making it impossible to draw a dividing line in Northwestern Europe (del Hoyo et al. 1996, Snow and Perrins 1998). The nominate subspecies of Common Ringed Plover is (C. h. hiaticula ) which breeds from southern Scandinavia to Great Britain, and northwestern France (Wiersma et al. 2019). This subspecies winters from Great Britain, south into Africa (del Hoyo et al. 1996, Snow and Perrins 1998). The second subspecies of the Common Ringed Plover is (C. h. tundrae) which is found breeding from northern Scandinavia, and northern Russia east to the Chukotskiy Peninsula, and is a casual breeder also in the northern Bering Sea region of Alaska on St Lawrence Island (Wiersma et al. 2019). This subspecies winters in the Caspian Sea region, and from Southwest Asia, south and east to South Africa (Wiersma et al. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

AVIAN PARAMYXOVIRUSES in SHOREBIRDS and Gulls

journal Diseases, 46(2), 2010, pp. 481-487 \Vildlife Disease Association 2010 AVIAN PARAMYXOVIRUSES IN SHOREBIRDS AND GUllS laura l. Coffee,1,5 Britta A. Hanson,' M. Page Luttrell;' David E. Swa~ne,2 Dennis A. Senne,3 Virginia H. Goekjlan," lawrence J. Niles,4,6 and David E. Stallknecht1, 1 Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, Departrnent of Population Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, USA 2 Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, US Departrnent of Agriculture, Athens, Georgia 30605, USA 3 US Departrnent of Agriculture, Anirnal and Plant Health Inspection Service, National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames, Iowa 50010, USA 4 Endangered and Nongame Species Program, New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife, PO Box 400, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, USA 5 Current address: Cornell University, College of Veterinary Medicine, S2-118 Schurman Hall, Biomedical Sciences, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA 6 Current address: Conserve Wildlife Foundation, 516 Farnsworth Avenue, Bordertown, New Jersey 08505, USA 7 Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: There are nine serotypes of avian paramyxovirus (APMV), including APMV-1, or Newcastle disease virus. Although free-flying ducks and geese have been extensively monitored for APMV, limited information is available for species in the order Charadriiforrnes. From 2000 to 2005 we tested cloacal swabs from 9,128 shorebirds and gulls (33 species, five families) captured in 10 states within the USA and in three countries in the Caribbean and South America. Avian paramyxoviruses were isolated from 60 (0.7%) samples by inoculation of embryonating chicken eggs; isolates only included APMV-1 and APMV-2. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Bird Monitoring at Zackenberg, Northeast Greenland, 2010, with Comparrison with 1996-20091,2

Bird Populations 11:42-51 © The Institute for Bird Populations 2012 BIRD MONITORING AT ZACKENBERG, NORTHEAST GREENLAND, 2010, WITH COMPARRISON WITH 1996-20091,2 JANNIK HANSEN3, LARS HOLST HANSEN AND NIELS MARTIN SCHMIDT Department of Bioscience Aarhus University P.O. Box 358 DK-4000 Roskilde, Denmark JEROEN RENEERKENS Animal Ecology Group Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Studies University of Groningen PO Box 14 9750 AA Haren, The Netherlands Abstract. In 2010, bird populations continue to be monitored in a 15.8 km2 designated area at Zackenberg Research Station in central Northeast Greenland. Results are presented and compared with those from previous seasons (1995 – 2009). The breeding bird census resulted in densities generally comparable with previous years, but with relatively high densities of Sanderling (Calidris alba) and Dunlin (Calidris alpina). For all wader species, nesting was early compared to previous years, but with extremely low nest success. The number of Long-tailed Skua (Stercorarius longicaudus) territories was lower than average, and only one pair nested (unsuccessfully) in the census area, reflecting a season with very low lemming numbers. For Barnacle Geese (Branta leucopsis), the mean brood size was low early in the season, but later in the season numbers were close to average. Key words: Monitoring, Arctic, waders, geese, Lapland bunting, Long-tailed Skua, Rock Ptarmigan, Snow Bunting, climate. MONITOREO DE AVES EN ZACKENBERG, NORESTE DE GROENLANDIA, 2010, CON UNA COMPARACION CON 1996-2009 Resumen. En 2010, el monitoreo de poblaciones de aves continuó en un área de 15.8 km2 designada en la Estación de Investigación de Zackenberg, en el centro del noreste de Groenlandia. -

Bird Observations in Siriuspasset, North Greenland, 2016 and 2017

Bird observations in Siriuspasset, North Greenland, 2016 and 2017 WON YOUNG LEE (Med et dansk resumé: Fugleobservationer i Siriuspasset, Nordgrønland, 2016 og ’17) Abstract During the summer seasons of 2016 and 2017, bird observations were recorded near Siriuspasset in Nansen Land, North Greenland. Breeding birds were surveyed in a 9 km2 area. Wader populations were dense compared to other sites in North and Northeast Greenland, and Red Phalarope Phalaropus fulicarius and Lapland Longspur Calca- rius lapponicus were found to breed far north of their previously known distributions in Greenland. Introduction Description of the study area and methods During the summers of 2016 and 2017, a Danish-Korean The study site was located on the east shore of J. P. Koch expedition performed biological and paleontological Fjord at the southwestern end of Siriuspasset, at alti- studies near Siriuspasset in Nansen Land, North Green- tudes of 0-300 m a.s.l., and here a well-vegetated area land. Compared to the North Greenland region as a of 9 km2 was censused for breeding birds (Figs 1 & 2). whole, Siriuspasset and its surroundings have very lush This was delimited by the coast, a river and features in vegetation, comparable to areas 900 km to the south in the terrain. Northeast Greenland (cf. Fig. 20 in Aastrup et al. 2005). From 25 July to 13 August, 2016 and 30 June to 21 Siriuspasset is a well-known habitat for both muskoxen July, 2017 breeding birds were monitored daily in the Ovibos moschatus and wolves Canis lupus, and high census area. In both years, the survey periods were actu- numbers of moulting Pink-footed Geese Anser brachyr- ally too late to census breeding waders, as failed breed- rhynchus were recorded there in 2009 during an aerial ers may have left by then (cf. -

Conservation Biology of the Endangered St. Helena Plover Charadrius Sanctaehelenae

Conservation biology of the endangered St. Helena Plover Charadrius sanctaehelenae Volume 1 of 1 Fiona Ewing Burns A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Biology and Biochemistry June 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author This thesis may be made available for consultation within the University Library and may be photocopied or lent to other libraries for the purposes of consultation. 1 Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................5 Introduction.......................................................................................................................6 Chapter 1: Leg flags versus colour rings: a comparison of marking methods using a small shorebird, the St Helena Plover.............................................................................20 Chapter 2: The impact of introduced predators on an island endemic, the St. Helena Plover Charadrius sanctaehelenae .................................................................................33 -

Arenaria Interpres (Ruddy Turnstone)

Arenaria interpres (Ruddy Turnstone) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 4 Sources of reported national population data p. 7 Species factsheet bibliography p. 10 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Arenaria interpres (Ruddy Turnstone) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

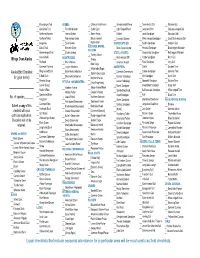

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's