Unity in Diversity: a Multicultural Education Program Designed to Promote Tolerance and an Appreciation of Human Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity for Peace: India's Cultural Spirituality

Cultural and Religious Studies, January 2017, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1-16 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2017.01.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Diversity for Peace: India’s Cultural Spirituality Indira Y. Junghare University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA In this age, the challenges of urbanization, industrialization, globalization, and mechanization have been eroding the stability of communities. Additionally, every existence, including humans, suffers from nature’s calamities and innate evolutionary changes—physically, mentally, and spiritually. India’s cultural tradition, being one of the oldest, has provided diverse worldviews, philosophies, and practices for peaceful-coexistence. Quite often, the multi-faceted tradition has used different methods of syncretism relevant to the socio-cultural conditions of the time. Ideologically correct, “perfect” peace is unattainable. However, it seems necessary to examine the core philosophical principles and practices India used to create unity in diversity, between people of diverse races, genders, and ethnicities. The paper briefly examines the nature of India’s cultural tradition in terms of its spirituality or philosophy of religion and its application to social constructs. Secondarily, the paper suggests consideration of the use of India’s spirituality based on ethics for peaceful living in the context of diversity of life. Keywords: diversity, ethnicity, ethics, peace, connectivity, interdependence, spiritual Introduction The world faces conflicts, violence, and wars in today’s world of globalization and due to diversity of peoples, regarding race, gender, age, class, birth-place, ethnicity, religion, and worldviews. In addition to suffering resulting from conflicts and violence arising from the issues of dominance and subservience, we have to deal with evolutionary changes. -

Blackhorse V. Pro Football

THIS OPINION IS A PRECEDENT OF THE TTAB Hearing: Mailed: March 7, 2013 June 18, 2014 UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _____ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board _____ Amanda Blackhorse, Marcus Briggs-Cloud, Philip Gover, Jillian Pappan, and Courtney Tsotigh v. Pro-Football, Inc. _____ Cancellation No. 92046185 _____ Jesse A. Witten, Jeffrey J. Lopez, John D. V. Ferman, Lee Roach and Stephen Wallace of Drinker, Biddle & Reath LLP for Amanda Blackhorse, Marcus Briggs, Philip Gover, Jillian Pappan, and Courtney Tsotigh. Robert L. Raskopf, Claudia T. Bogdanos and Todd Anten of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP for Pro-Football, Inc. _____ Before Kuhlke, Cataldo and Bergsman, Administrative Trademark Judges. Opinion by Kuhlke, Administrative Trademark Judge: OVERVIEW Petitioners, five Native Americans, have brought this cancellation proceeding pursuant to Section 14 of the Trademark Act of 1946, 15 U.S.C. § 1064(c). They seek to cancel respondent’s registrations issued between 1967 and 1990 for Cancellation No. 92046185 trademarks consisting in whole or in part of the term REDSKINS for professional football-related services on the ground that the registrations were obtained contrary to Section 2(a), 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a), which prohibits registration of marks that may disparage persons or bring them into contempt or disrepute. In its answer, defendant, Pro-Football, Inc., asserted various affirmative defenses including laches.1 As explained below, we decide, based on the evidence properly before us, that these registrations must be cancelled because they were disparaging to Native Americans at the respective times they were registered, in violation of Section 2(a) of the Trademark Act of 1946, 15 U.S.C. -

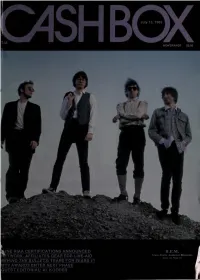

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Peace and Dignity: More Than the Absence of Humiliation – What We Can Learn from the Asia-Pacific Region

Peace and Dignity: More than the Absence of Humiliation – What We Can Learn from the Asia-Pacific Region Evelin G. Lindner, M.D., Ph.D. (Dr. med. and Dr. psychol.) Social Scientist Founding President of Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies (HumanDHS, www.humiliationstudies.org/) - affiliated with the University of Oslo, Department of Psychology, Norway (folk.uio.no/evelinl/, [email protected]) - affiliated with the Columbia University Conflict Resolution Network, New York ([email protected]) - affiliated with the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, Paris - teaching, furthermore, in South East Asia, the Middle East, Australia, and other places globally (www.humiliationstudies.org/whoweare/evelin.php) - watch the introductory lecture "Dignity or Humiliation: The World at a Crossroad," given at the University of Oslo, Norway, on January 2009, at www.sv.uio.no/it/av/PSYC3203-14.1.09.html This paper was written for The Australian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies: Occasional Papers Series in 2009, however, since this series closed in December 2009, it is published on www.humiliationstudies.org/whoweare/evelin02.php. November 2009 Abstract In an interdependent world, peace is not optional, it is compulsory, if humankind is to survive. Local conflicts, particularly protracted conflicts, are inscribed into, and taken hostage by larger global pressures, and vice versa, and this diffuses insecurity. Peace is more than resolved conflict. What is needed is the pro-active creation of global social cohesion. In an interdependent world, security is no longer attainable through keeping enemies out but only through keeping a compartmentalised world together. How do we, as humankind, keep a disjointed world together in a pro-active way? And how can Asia contribute to this task? This is the topic of this paper. -

Kansas City Chiefs Dating Show

Feb 05, · From day one, Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce has been the guy in town. From his talent level to his sense of humor to his fashion choices to his dating show (I . Well, it seems Maya Benberry has heard the chatter about the health of her relationship with Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce. Benberry was Kelce’s choice in the reality dating show “Catching Kelce,”. "The Franchise" presented by GEHA is an all-access look at the Kansas City Chiefs through the eyes of the players, coaches and leadership, on and off the field. Streaming on Chiefs YouTube, Chiefs Facebook Watch and renuzap.podarokideal.rug: dating show. Jul 06, · KANSAS CITY, MO – FEBRUARY Fans stand for several hours in below freezing temperatures for the Kansas City Chiefs Victory Parade on February 5, in Kansas City, renuzap.podarokideal.rug: dating show. Feb 01, · NFL's Kansas City Chiefs, one of several American sports teams that copy Native American imagery and traditions, will take the field for Super Bowl LIV. How did the team, which was founded in Missing: dating show. 1 day ago · Last year, the Kansas City Chiefs had a total of six players make the list including Patrick Mahomes, Tyreek Hill, Travis Kelce, Chris Jones, Mitchell Schwartz and Frank Clark. Yahoo Sports’ Terez Paylor reports that, once again, Kansas City will have six players on the top renuzap.podarokideal.rug: dating show. Jul 21, · There could be a battle brewing for the Chiefs’ WR3 position How Kansas City’s wide receiver room is shaping up heading into the season. -

Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” in Forming Harmony of Multicultural Society

Unconsidered Ancient Treasure, Struggling the Relevance of Fundamental Indonesia Nation Philosophie “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” in Forming Harmony of Multicultural Society Fithriyah Inda Nur Abida, State University of Surabaya, Indonesia Dewi Mayangsari, Trunojoyo University, Indonesia Syafiuddin Ridwan, Airlangga University, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Cultural Studies Official Conference Proceedings 0139 Abstract Indonesia is a multicultural country consists of hundreds of distinct native ethnic, racist, and religion. Historically, the Nation was built because of the unitary spirit of its components, which was firmly united and integrated to make up the victory of the Nation. The plurality become advantageous when it reach harmony as reflected in the National motto “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika”. However, plurality also issues social conflict easily. Ever since its independence, the scent of disintegration has already occurred. However, in the last decade, social conflicts with a variety of backgrounds are intensely happened, especially which is based on religious tensions. The conflict arises from differences in the interests of various actors both individuals and groups. It is emerged as a fractional between the groups in the society or a single group who wants to have a radically changes based on their own spiritual perspective. Pluralism is not a cause of conflict, but the orientation which is owned by each of the components that determine how they’re viewing themselves psychologically in front of others. “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” is an Old Javanese phrase of the book “Sutasoma” written by Mpu Tantular during the reign of the Majapahit sometime in the 14th century, which literally means “Diverse, yet united” or perhaps more poetically in English: Unity in Diversity. -

Unity in Diversity in Indian Society Sociology / GE / Semester-II

Unity in Diversity in Indian Society Sociology / GE / Semester-II India is a plural society both in letter and spirit. It is rightly characterized by its unity and diversity. A grand synthesis of cultures, religions and languages of the people belonging to different castes and communities has upheld its unity and cohesiveness despite multiple foreign invasions. National unity and integrity have been maintained even through sharp economic and social inequalities have obstructed the emergence of egalitarian social relations. It is this synthesis which has made India a unique mosque of cultures. Thus, India present seemingly multicultural situation within in the framework of a single integrated cultural whole. The term ‘diversity’ emphasizes differences rather than inequalities. It means collective differences, that is, differences which mark off one group of people from another. These differences may be of any sort: biological, religious, linguistic etc. Thus, diversity means variety of races, of religions, of languages, of castes and of cultures. Unity means integration. It is a social psychological condition. It connotes a sense of one-ness, a sense of we-ness. It stands for the bonds, which hold the members of a society together. Unity in diversity essentially means “unity without uniformity” and “diversity without fragmentation”. It is based on the notion that diversity enriches human interaction. When we say that India is a nation of great cultural diversity, we mean that there are many different types of social groups and communities living here. These are communities defined by cultural markers such as language, religion, sect, race or caste. Various forms of diversity in India: Religious diversity: India is a land of multiple religions. -

Unity in Diversity? How Intergroup Contact Can Foster Nation Building∗

Unity in Diversity? How Intergroup Contact Can Foster Nation Building∗ Samuel Bazziy Arya Gaduhz Alexander Rothenbergx Maisy Wong{ Boston University University of Arkansas RAND Corporation University of Pennsylvania and CEPR February 2018 Abstract Ethnic divisions complicate nation building, but little is known about how to mitigate these divisions. We use one of history’s largest resettlement programs to show how intergroup contact affects long-run integration. In the 1980s, the Indonesian government relocated two million migrants into hundreds of new communities to encourage interethnic mixing. Two decades later, more diverse communities exhibit deeper integration, as reflected in language use and intergroup marriage. Endogenous sor- ting across communities cannot explain these effects. Rather, initial conditions, including residential segregation, political and economic competition, and linguistic differences influence which diverse communities integrate. These findings contribute lessons for resettlement policy. JEL Classifications: D02, D71, J15, O15, R23 Keywords: Cultural Change, Diversity, Identity, Language, Migration, Nation Building ∗We thank Alberto Alesina, Oriana Bandiera, Toman Barsbai, Giorgio Chiovelli, Raquel Fernandez, Paola Giuliano, Dilip Mookherjee, Nathan Nunn, Daniele Paserman, Ben Olken, Imran Rasul and seminar participants at Boston University, George- town University, Harvard University, the Kiel Institute, McGill University, MIT, Notre Dame, University of Colorado Denver, University of Southern California, University -

Maddra, Sam Ann (2002) 'Hostiles': the Lakota Ghost Dance and the 1891-92 Tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Phd Thesi

Maddra, Sam Ann (2002) 'Hostiles': the Lakota Ghost Dance and the 1891-92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3973/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] `Hostiles':The LakotaGhost Danceand the 1891-92 Tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Vol. II Sam Ann Maddra Ph.D. Thesis Department of Modern History Facultyof Arts University of Glasgow December2002 203 Six: The 1891/92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Dance shovestreatment of the Lakota Ghost The 1891.92 tour of Britain by Buffalo Bill's Wild West presented to its British audiencesan image of America that spokeof triumphalism, competenceand power. inside This waspartly achievedthrough the story of the conquestthat wasperformed the arena, but the medium also functioned as part of the message,illustrating American power and ability through the staging of so large and impressivea show. Cody'sWild West told British onlookersthat America had triumphed in its conquest be of the continent and that now as a powerful and competentnation it wasready to recognisedas an equal on the World stage. -

The IX South-East European Gathering

The IX South-East European Gathering Budva, 25 – 27. May, 2012 Speech by Dr Zlatko Lagumdžija, Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the IX South-East European Gathering – „E Pluribus Unum“ and „United in Diversity“ Ladies and gentlemen, It is a great pleasure and a great honour to stand here before this respective audience and give a speech at the IX South-East European Gathering. Looking at the brochure/invitation of this distinguished program I noticed a phrase. “E PLURIBUS UNUM”! 1. “E PLURIBUS UNUM” and the United States of America This phrase, which is present on the Seal of the United States and which is de facto motto of the United States (de facto since it was never codified- official motto of the US is “In God We Trust) tells us a lot about American society. "E Pluribus Unum" was the motto proposed for the first Great Seal of the United States by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson in 1776. A Latin phrase meaning "One from many," the phrase offered a strong statement of the American determination to form a single nation from a collection of states. Over the years, "E Pluribus Unum" has also served as a reminder of America's attempt to make one unified nation of people from many different backgrounds and beliefs. The challenge of seeking unity while respecting diversity has played a critical role in shaping US history, US literature, and US national character. Originally suggesting that out of many colonies or states emerge a single nation, in recent years it has come to suggest that out of many peoples, races, religions and ancestries has emerged a single people and nation where “all men are created equal” as it is stated in the “Declaration of Independence”.1Thus, USA have been democratically developing its “One from many” society for more than two centuries. -

Congratulations, George. No Wonder They Call You "King"

A D V E R T I S E M E N T r EXPERIENCE THE BUZZ MA" 3 2003 56 NUMBER ONE SINGLES 32 PLATINUM ALBUMS COUNTRY MUSIC HALL OF FAME MEMBER COUNTRY ALBUM OF THE YEAR Congratulations, George. No wonder they call you "King" www.billboand.com www.billboerd.biz US $6.99 CAN $8 99 UK £5.50 99uS Y8.:9CtiN 18> MCA NASHVILLE #13INCT - SCII 3 -DIGIT 907 413124083434 MARI0 REG A04 000!004 s, 200: MCA Nashville 'lllllllliLlllllllulii llll IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIfII I MONTY G2EENIY 0027 l 3740 ELA AVE 4 P o 1 96 L7-Z0`_ 9 www.GeorgeStrait.co LONG BE.1CB CA 90807 -3 IC? "001160 www.americanradiohistory.com ATTENTION INDIE MUSICIANS! THE IMWS IS NOW ACCEPTING ENTRIES. DISC MAKERS" Independent Music World Series In 2008, the IMWS will award over $250,000 in cash GOSPEL, METAL, and prizes to independent musicians. No matter HIP HOP, PUNK, where you live, you are eligible to enter now! JAZZ, COUNTRY, EMO, ROCK, RAP, Whatever your act is... REGGAETON, we've showcased your style of music. AND MANY MORE! Deadline for entries is May 14, 2008 2008 Showcases in LOS ANGELES, ATLANTA, CHICAGO, and NEW YORK CITY. VISIT WWW.DISCMAKERS.COM /08BILLBOARD TO ENTER, READ THE RULES AND REGULATIONS, FIND OUT ABOUT PAST SHOWCASES, SEE PHOTOS,AND LEARN ALL ABOUT THE GREAT IMWS PRIZE PACKAGE. CAN'T GET ONLINE? CALL 1 -888- 800-5796 FOR MORE INFO. i/, Billboard sonicbíds,- REMO `t¡' 0 SAMSON' cakewalk DRUM! Dc.!1/Watk4 Remy sHvRE SLIM z=rn EleCtronic Musicioo www.americanradiohistory.com THEATER TWEETERS CONCERTS CASH IN AT THE MOVIES >P.27 DEF JAMMED LIFE AFTER JAY-Z FOR THE ROOTS -

N° Artiste Titre Formatdate Modiftaille 14152 Paul Revere & the Raiders Hungry Kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben

N° Artiste Titre FormatDate modifTaille 14152 Paul Revere & The Raiders Hungry kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben Verliefd Op Jou kar 2004 48 860 14154 Paul Simon A Hazy Shade Of Winter kar 1995 18 008 14155 Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard kar 2001 41 290 14156 You Can Call Me Al kar 1997 83 142 14157 You Can Call Me Al mid 2011 24 148 14158 Paul Stookey I Dig Rock And Roll Music kar 2001 33 078 14159 The Wedding Song kar 2001 24 169 14160 Paul Weller Remember How We Started kar 2000 33 912 14161 Paul Young Come Back And Stay kar 2001 51 343 14162 Every Time You Go Away mid 2011 48 081 14163 Everytime You Go Away (2) kar 1998 50 169 14164 Everytime You Go Away kar 1996 41 586 14165 Hope In A Hopeless World kar 1998 60 548 14166 Love Is In The Air kar 1996 49 410 14167 What Becomes Of The Broken Hearted kar 2001 37 672 14168 Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home) kar 1999 40 481 14169 Paula Abdul Blowing Kisses In The Wind kar 2011 46 676 14170 Blowing Kisses In The Wind mid 2011 42 329 14171 Forever Your Girl mid 2011 30 756 14172 Opposites Attract mid 2011 64 682 14173 Rush Rush mid 2011 26 932 14174 Straight Up kar 1994 21 499 14175 Straight Up mid 2011 17 641 14176 Vibeology mid 2011 86 966 14177 Paula Cole Where Have All The Cowboys Gone kar 1998 50 961 14178 Pavarotti Carreras Domingo You'll Never Walk Alone kar 2000 18 439 14179 PD3 Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is kar 1998 45 496 14180 Peaches Presidents Of The USA kar 2001 33 268 14181 Pearl Jam Alive mid 2007 71 994 14182 Animal mid 2007 17 607 14183 Better