Draft Strategic Plan for the Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Region 2017 - 2026

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellabinna and Warna Manda Parks Draft Management Plan 2017

Yellabinna and Warna Manda Parks Draft Management Plan 2017 We are all custodians of the Yellabinna and Warna Manda parks, which are central to Far West Coast Aboriginal communities. Our culture is strong and our people are proud - looking after, and sharing Country. We welcome visitors. We ask them to appreciate the sensitivity of this land and to respect our culture. We want our Country to remain beautiful, unique and healthy for future generations to enjoy. Far West Coast Aboriginal people Yellabinna parks Warna Manda parks • Boondina Conservation Park • Acraman Creek Conservation Park • Pureba Conservation Park • Chadinga Conservation Park • Yellabinna Regional Reserve • Fowlers Bay Conservation Park • Yellabinna Wilderness Protection Area • Laura Bay Conservation Park • Yumbarra Conservation Park • Point Bell Conservation Park • Wahgunyah Conservation Park • Wittelbee Conservation Park Your views are important This draft plan has been developed by the Yumbarra Conservation Park Co-management Board. The plan covers five parks in the Yellabinna region – the Yellabinna parks. It also covers seven coastal parks between Head of the Bight and Streaky Bay - the Warna Manda parks. Warna Manda means ‘coastal land’ in the languages of Far West Coast Aboriginal people. Once finalised, the plan will guide the management of these parks. It will also help Far West Coast Aboriginal people to maintain their community health and wellbeing by supporting their connection to Country. Country is land, sea, sky, rivers, sites, seasons, plants and animals; and a place of heritage, belonging and spirituality. The Yellabinna and Warna Manda Parks Draft Management Plan 2017 is now released for public comment. Members of the community are encouraged to express their views on the draft plan by making a written submission. -

Domestic/Regional Travel – Jan 2019

Domestic/Regional Travel – Jan 2019 Minister Wingard and Ministerial Staff No of Travel Itinerary1 Travel Destination Reasons for Travel Cost of Travel2 travellers Receipts3 2 Eyre Peninsula Site visits and meetings Attached $323.20 Attached 2 York Peninsula Site visits and meetings Attached $293.70 Attached Example disclaimer - Note: These details are correct as at the date approved for publication. Figures may be rounded and have not been audited. 1 Scanned copies of itineraries to be attached (where available). 2 Excludes salary costs. 3 Scanned copies of all receipts/invoices to be attached. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (BY) 3.0 Australia Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ To attribute this material, cite Government of South Australia Eyre Peninsula Regional Trip Tuesday 22 January & Wednesday 23 January 2019 Tuesday 22 January 2019 7.00am‐7.50am Flight REX – Adelaide to Port Lincoln (50 mins) Drive from Port Lincoln Airport to Tumby Bay (24 mins) 8.45am‐9.30am SAPOL visit – Tumby Bay Police Station ‐ 5 Tumby Terrace, Tumby Bay 9.45am – 10.15am SES visit – Tumby Bay SES Unit ‐ 11 Excell Road, Tumby Bay 10.15am‐11.00am Drive from Tumby Bay to Arno Bay (45 mins) 11.15am‐11.45am CFS visit – Arno Bay CFS Unit ‐Cnr Third Street and First Street, Arno Bay 11.45am‐1.00pm Drive from Arno Bay to Pt Lincoln (1 hr 15 mins) 1.00pm – 2.00pm 2.00pm‐2.30pm Sport ‐ Port Lincoln Leisure Centre Stadium ‐ Jubilee Drive, Port Lincoln 2.45pm‐3.15pm MFS visit – Port Lincoln MFS Unit ‐ 45 St Andrews Terrace, -

Road Crash Register Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Detail Crash History

Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Road Crash Register Detail Crash History Report: TR0680 Report Date: 12/06/2018 10:35 Distribute To: BOGANKAT Total Pages: 45 Parameter Values Key Road Cross Road 1 Cross Road 2 LGA Regions Stats Areas 577 Crashes between : 01/01/2013 and 31/12/2017 RRD between : and Severity : Fatal + All Injuries Show AR Number ? Y Crash Types : Unit Types : Postcodes : Suburbs : DCA Codes Road Moisture Road Surfaces Lighting condition BOGANKAT Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Page 1 of 45 TR0680 Road Crash Register 12/06/2018 10:35 VERSION 10.06 Detailed Crash History LGA 577 : DC LOWER EYRE PENINSULA Key Road 0002600A LINCOLN HIGHWAY Region NORTHERN AND WESTERN Suburb BOSTON (5607) Stats Area 003 : Country MID-BLOCK BETWEEN 5770062M RICHARDSON ROAD BOSTON 5710159M KURLA STREET PORT LINCOLN Date Time Severity Damage Crash Type Road Road Lighting Traffic Controls Locn Type Report No. Surface Moisture 16/05/2014 09:00 Fri Injury $25,000 Right Angle Sealed Dry Daylight No Control Not Divided VC14230669 DCA Code Sub DCA Code(s) 149 Other Manoeuvring Event Code Evt Seq Unit 1 Unit 1 Object Unit 1 Col pt Unit 2 Unit 2 Object Unit 2 Col Pt COLLISION E RIGID TRUCK LGE GE 4.5T FRONT Motor Cars FRONT RRD: 0312.38 Motor Cars - Sedan - Stopped on Carriageway in North West direction(Towed From Scene) Hits a RIGID TRUCK LGE GE 4.5T - Straight Ahead in North East direction (Driver Rider resp)(Towed From Scene) Apparent Error Inattention Total Casualties 1 ( 1 inj minor, 0 inj serious, 0 fatals) MID-BLOCK BETWEEN 5770158M GLEDSTANES TERRACE BOSTON 5770063M HAIGH DRIVE BOSTON Date Time Severity Damage Crash Type Road Road Lighting Traffic Controls Locn Type Report No. -

Strategic Plan for the Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Region - 2017-2027 Far West

Strategic Plan for the Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Region - 2017-2027 Far West Agricultural land near Streaky Bay The Far West includes Quick stats a large marine area extending along the Population: Main land uses Great Australian Bight Approximately 6,270 (2011) (% of land area): to beyond the Nuyts Major towns (population): Dryland agriculture (cropping and grazing) Archipelago, nearly 80km (52% of total land area) Ceduna (approx. pop 2,290) Conservation (46%) offshore. The land area Streaky Bay (approx. pop 1,000) Minnipa (350) Main industries: extents from Wahgunyah Venus Bay (320) Agriculture Conservation Reserve in Smoky Bay (195 Aquaculture Traditional Owners: Fishing, the West to Minnipa in Health care the east, and south to Mirning nation Social assistance Wirangu nation Retail trade Venus Bay. Kokatha nation Annual Rainfall: Local Governments: 270 - 380 mm District Council of Ceduna Highest elevation: District Council of Streaky Bay Land Area: Tcharkuldu Hill (215 metres AHD) Coastline length: Approximately 22,200 square kilometres 1083 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 53 54 | Strategic Plan for the Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Region 2017-2027 Figure 21 – Map of Far West subregion Quick stats What’s valued in Far West The tyranny of distance is felt by many in the community who value the remoteness of the region but sometimes struggle to The beautiful, clean beaches, rocky cliffs, great fishing and access services and facilities available in more populated areas. remoteness of the Far West are highly valued by the local Broad scale cropping and grazing is undertaken across large areas community and visitors to the area. -

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): SAD6011/1998 NNTT Number: SCD2016/001 Determination Name: Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia Date(s) of Effect: 6/04/2018 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in parts of the determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 23/06/2016 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Note 1: On 6 April 2018 Justice White of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) ordered that: 1. The Determination of native title made on 23 June 2017 [sic] in Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia (No 2) [2016] FCA 724 be amended in accordance with the Amended Determination attached as Annexure A to this order, noting that because of the size of the Determination Annexure A comprises only: a. pages i to xv inclusive of the Amended Determination; b. the first page of any Schedule which is amended; and c. the particular pages within each Schedule which are amended. 2. Order 2 made on 23 June 2016 be vacated. 3. In its place there be an order that the Determination as amended take effect from the date of this order. Note 2: In the Determination orders of 23 June 2016, Order 22 deals with the nomination of a prescribed body corporate. On 19 December 2016 the applicant nominated to the Court in accordance with sections 56 and 57 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that: (a) native title is not to be held in trust; National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 20 Extract from the National Native Title Register SCD2016/001 and, accordingly, pursuant to Order 22(b) of 23 June 2016: (b) the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation is nominated as the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of section 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). -

Preserving the West Coast of South Australia 2 Contents

WRITTEN BY DAVID LETCH Chain of Bays PHOTOGRAPHY BY GRANT HOBSON Preserving the West Coast of South Australia 2 Contents chapter 1 Preserving a unique coastal area 5 chapter 2 The Wirangu people 11 chapter 3 Living in a wild coastal ecosystem 17 chapter 4 Scientists, surfers, naturalists & tourists 21 chapter 5 Regulating impacts on nature 25 chapter 6 Tyringa & Baird Bay 31 chapter 7 Searcy Bay 37 chapter 8 Sceale Bay 41 chapter 9 Corvisart Bay 47 chapter 10 Envisaging the long term 49 chapter 11 Local species lists 51 chapter 12 Feedback & getting involved in conservation 55 chapter 12 References 57 chapter 12 Acknowledgements 59 Front cover image: Alec Baldock and Juvenile Basking Shark (1990). The taxonomy and traits of many species can remain a mystery. This image was sent to the Melbourne Museum where the species was identified - a rare image collected locally. Back cover image: Crop surrounding a pocket of native vegetation (2009). Much land has been cleared for farming in the Chain of Bays. Small tracts of native vegetation represent opportunities for seed collection and habitat preservation. Connecting these micro habitats is the real challenge. Inside cover: Cliff top vegetation Tyringa (2009). In the Chain of Bays sensitive vegetation clings to the calciferous limestone cliffs. Off road vehicles and quad bikes pose an increasing threat in the Chain of Bays. Right image: Death Adder Sceale Bay (2010). These beautiful and highly venomous reptiles are very rarely seen by local people suggesting their numbers may be low in the area. -

Musgrave Subregional Description

Musgrave Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix D The Musgrave subregion extends from Mount Camel Beach in the north inland to the Tod Highway, and then south to Lock and then west across to Lake Hamilton in the south. It includes the Southern Ocean including the Investigator Group, Flinders Island and Pearson Isles. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 1,050 Major towns (population): Elliston (300), Lock (340) Traditional Owners: Nauo and Wirangu nations Local Governments: District Council of Elliston, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and Wudinna District Council Land Area: Approximately 5,600 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Grazing (30% of total land area), conservation (20% of land area), cropping (18% of land area) Main industries: Agriculture, health care, education Annual Rainfall: 380 - 430mm Highest Elevation: Mount Wedge (249 metres AHD) Coastline length: 130 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 12 2 Musgrave Subregional Description Musgrave What’s valued in Musgrave Pearson Island is a spectacular The landscapes and natural resources of the Musgrave unspoilt island with abundant and subregion are integral to the community’s livelihoods and curious wildlife. lifestyles. The Musgrave subregion values landscapes include large The coast is enjoyed by locals and visitors for its beautiful patches of remnant bush and big farms. Native vegetation landscapes, open space and clean environment. Many is valued by many in the farming community and many local residents particularly value the solitude, remoteness recognise its contribution to ecosystem services, and and scenic beauty of places including Sheringa Beach, that it provides habitat for birds and reptiles. -

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys Australis 2012

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis 2012 - 1 - This plan should be cited as follows: Moseby, K. (2012) National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Published by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Adopted under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: [date to be supplied] ISBN : 978-0-9806503-1-0 © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Government of South Australia. Requests and inquiries regarding reproduction should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Note: This recovery plan sets out the actions necessary to stop the decline of, and support the recovery of, the listed threatened species or ecological community. The Australian Government is committed to acting in accordance with the plan and to implementing the plan as it applies to Commonwealth areas. The plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a broad range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Queensland disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. -

Plastic Packing Bands Bibliography

Plastic Packing Bands Bibliography Katie Rowley, Librarian, NOAA Central Library NCRL subject guide 2021-02 https://doi.org/10.25923/457t-j775 April 2021 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research NOAA Central Library – Silver Spring, Maryland Table of Contents Background & Scope ................................................................................................................................. 2 Sources Reviewed ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Section I: Marine Impact of Plastic (Packing Bands) ................................................................................. 3 Section II: Pinniped and Marine Species ................................................................................................. 14 Section III: Seabirds ................................................................................................................................. 25 Section IV: Policy ..................................................................................................................................... 27 Section V: Alternatives & Technology ..................................................................................................... 30 1 Background & Scope The National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region Protected Resources Division requested an annotated bibliography on the impacts of plastic packing bands (straps) -

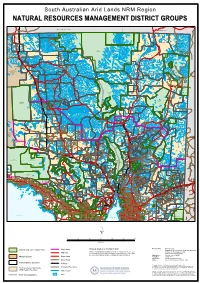

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

General Intro

For further information, please contact: Coast and Marine Conservation Branch Department of Environment and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 8124 4900 Facsimile: (08) 8124 4920 Cite as: Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2010), Environmental, Economic and Social Values of the Thorny Passage Marine Park, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, South Australia Mapping information: All maps created by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources unless otherwise stated. All Rights Reserved. All works and information displayed are subject to Copyright. For the reproduction or publication beyond that permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth) written permission must be sought from the Department. Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information displayed, the Department, its agents, officers and employees make no representations, either express or implied, that the information displayed is accurate or fit for any purpose and expressly disclaims all liability for loss or damage arising from reliance upon the information displayed. © Copyright Department of Environment and Natural Resources 2010. 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 VALUES STATEMENT 1 ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 ECOSYSTEM SERVICES...............................................................................................................................1 1.2 PHYSICAL INFLUENCES -

Eyre Peninsula OCEAN 7

Mount F G To Coober Pedy (See Flinders H I Olympic Dam J Christie Ranges and Outback Region) Village Andamooka Wynbring Roxby Downs To Maralinga Lyons Tarcoola WOOMERA PROHIBITED AREA (Restricted Entry) Malbooma 87 Lake Lake Younghusband Ferguson Patricia 1 1 Glendambo Kingoonya Lake Hanson Lake Torrens 'Coondambo' Lake Yellabinna Regional Kultanaby Lake Hart National Park Lake Harris Wirramn na Woomera Reserve Lake Torre Lake Lake Gairdner Pimba Windabout ns Everard National Park Pernatty Lagoon Island Wirrappa See map on opposite Lake page for continuation Lagoon Dog Fence 'Oakden Hill' Gairdner 'Mahanewo' 2 Yumbarra Conservation Stuart 2 Park 'Lake Everard' Lake Finnis 'Kangaroo To Nundroo (See OTC Earth Wells' 'Yalymboo' Lake Dutton map opposite) Station Bookaloo Pureba Conservation 'Moonaree' Lake Highway Penong 57 1 'Kondoolka' Lake MacFarlane Park 16 Acraman 'Yadlamalka' 59 Nunnyah Con. Res Ceduna 'Yudnapinna' Mudlamuckla 'Hiltaba' Jumpuppy Hesso To Hawker (See Bay Hill Flinders and Koolgera Cooria Hill Outback Region) Point Bell 41 Con. Res 87 Murat Smoky Mt. Gairdner 51 Goat Is. Bay 93 33 Unalla Hill 'Low Hill' St. Peter Smoky Bay Horseshoe Evans Is. Gawler Tent Hill Quorn Island 29 27 Barkers Hill 'Cariewerloo' Hill Eyre Wirrulla 67 'Yardea' 'Mount Ive' Nuyts Archipelago Is. Conservation Haslam 'Thurlga' 50 'Nonning' Park Flinders Port Augusta St. Francis Point Brown 76 Paney Hill Red Hill Streaky 46 25 3 Island 75 61 3 Bay Eyre 'Paney' Ranges Highway Army 27 Harris Bluff 'Corunna' Training Cape Bauer 39 28 43 Poochera Lake Area Olive Island 61 Iron Knob 33 45 Gilles Corvisart Highway 'Buckleboo' Streaky Bay Lake Gilles 47 Bay Minnipa Pinkawillinie Conservation Park 1 56 17 31 Point Westall 21 Highway Conservation Buckleboo 21 35 43 Eyre Sceale Bay 17 Park Iron Baron 88 Cape Blanche 43 13 27 23 Wudinna 24 24 Port Germein Searcy Bay Kulliparu Kyancutta 18 Whyalla Point Labatt Port Kenny 22 Con.