APPENDIX D Cultural Resources Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOGRAPHIES, INTERVIEWS, ITINERARIES, WRITINGS & NOTES BOX 1: BIOGRAPHY,1940S-1950S

HOLT ATHERTON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MS4: BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 1: PAPERS SUBSERIES D: BIOGRAPHIES, INTERVIEWS, ITINERARIES, WRITINGS & NOTES BOX 1: BIOGRAPHY,1940s-1950s 1D.1.1: Biography, 1942: “Iola Whitlock marries Dave Brubeck,” Pacific Weekly, 9-25-42 1.D.1.2: Biography, 1948: Ralph J. Gleason. “Long awaited Garner in San Francisco…Local boys draw comment” [Octet at Paradise in Oakland], Down Beat (12-1-48), pg. 6 1.D.1.3: Biography, 1949 a- “NBC Conservatory of Jazz,” San Francisco, Apr 5, 1949 [radio program script for appearance by the Octet; portion of this may be heard on Fantasy recording “The Dave Brubeck Octet”; incl. short biographies of all personnel] b- Lifelong Learning, Vol. 19:6 (Aug 8, 1949) c- [Bulletin of University of California Extension for 1949-50, the year DB taught “Survey of Jazz”] d- “Jazz Concert Set” 11-4-49 e- Ralph J. Gleason. “Finds little of interest in lst Annual Jazz Festival [San Francisco],” Down Beat (12-16-49) [mention of DB Trio at Burma Lounge, Oakland; plans to play Ciro’s, SF at beginning of 1950], pg. 5 f- “…Brubeck given musical honors” Oakland Tribune, December 16, 1949 g- DB “Biographical Sketch,” ca Dec 1949 h- “Pine Tree Club Party at Home of Mrs. A. Ellis,” <n.s.> n.d. [1940s] i- “Two Matrons are Hostesses to Pine Tree Club,” <n.s.> n.d. [1940s] (on same page as above) 1.D.1.4: Biography, 1950: “Dave Brubeck,” Down Beat, 1-27-50 a- Ralph J. Gleason. “Swingin the Golden Gate: Bay Area Fog,” Down Beat 2- 10-50 [DB doing radio show on ABC] 1.D.1.5: BIOGRAPHY, 1951: “Small band of the year,” Jazz 1951---Metronome Yearbook, n.d. -

Shall We Stomp?

Volume 36 • Issue 2 February 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Shall We Stomp? The NJJS proudly presents the 39th Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp ew Jersey’s longest Nrunning traditional jazz party roars into town once again on Sunday, March 2 when the 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp is pre- sented in the Grand Ballroom of the Birchwood Manor in Whippany, NJ — and you are cordially invited. Slated to take the ballroom stage for five hours of nearly non-stop jazz are the Smith Street Society Jazz Band, trumpeter Jon Erik-Kellso and his band, vocalist Barbara Rosene and group and George Gee’s Jump, Jivin’ Wailers PEABODY AT PEE WEE: Midori Asakura and Chad Fasca hot footing on the dance floor at the 2007 Stomp. Photo by Cheri Rogowsky. Story continued on page 26. 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp MARCH 2, 2008 Birchwood Manor, Whippany TICKETS NOW AVAILABLE see ad page 3, pages 8, 26, 27 ARTICLES Lorraine Foster/New at IJS . 34 Morris, Ocean . 48 William Paterson University . 19 in this issue: Classic Stine. 9 Zan Stewart’s Top 10. 35 Institute of Jazz Studies/ Lana’s Fine Dining . 21 NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Jazz from Archives. 49 Jazzdagen Tours. 23 Big Band in the Sky . 10 Yours for a Song . 36 Pres Sez/NJJS Calendar Somewhere There’s Music . 50 Community Theatre. 25 & Bulletin Board. 2 Jazz U: College Jazz Scene . 18 REVIEWS The Name Dropper . 51 Watchung Arts Center. 31 Jazzfest at Sea. -

US Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay

NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, ADMINISTRATION AND HABS Hl-311-P OPERATIONS BUILDING HABS H/-311-P (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) E Street between 3rd and 4th streets Kq1n,@0t1e Honolulu County Hawaii PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY U.S. NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, OAHU, ADMINISTRATION AND OPERATIONS BUILDING (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) HABS No. Hl-311-P Location: Honolulu County, Hawaii U.S.G.S. Mokapu Point quadrangle, 1998 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic) (Scale - 1 :24,000) NAD83 datum. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 04.628510.2371690. Lat./ Long. Coordinates: 21 °26'35.05" N 157°45'35.45" W Date of Construction: 1941 Designer: Albert Kahn, Inc., Detroit, Michigan Builder: Contractors, Pacific Naval Air Bases Owner: U.S. Marine Corps Present Use: Offices Significance: Facility 215, Administration and Operations Building, is significant for its association with U.S. Naval Air Station (NAS) Kaneohe and its role before the onset of World War II (WWII) in the Pacific. It was one of the primary buildings during the establishment of the U.S. Naval Air Station Kaneohe and headquarters for the station coll1111ander. The building contained the offices for numerous important administrative and coll1111unication functions of the station. The ca. 1939 building is also significant as a part of the original design of the station. In addition, Facility 215 at Kaneohe, along with forty-three other facilities there, is significant because it embodies distinctive characteristics of building types in this period that were designed by the notable architectural firm of Albert Kahn, Inc. -

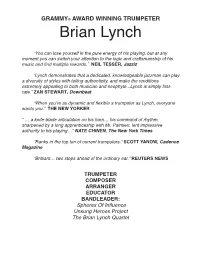

2013 Brian Lynch Full Press Kit(Bio-Discog

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch “You can lose yourself in the pure energy of his playing, but at any moment you can switch your attention to the logic and craftsmanship of his music and find multiple rewards.” NEIL TESSER, Jazziz “Lynch demonstrates that a dedicated, knowledgeable jazzman can play a diversity of styles with telling authenticity, and make the renditions extremely appealing to both musician and neophyte...Lynch is simply first- rate.” ZAN STEWART, Downbeat “When you’re as dynamic and flexible a trumpeter as Lynch, everyone wants you.” THE NEW YORKER “ … a knife-blade articulation on his horn… his command of rhythm, sharpened by a long apprenticeship with Mr. Palmieri, lent impressive authority to his playing…” NATE CHINEN, The New York Times “Ranks in the top ten of current trumpeters.” SCOTT YANOW, Cadence Magazine “Brilliant… two steps ahead of the ordinary ear.” REUTERS NEWS TRUMPETER COMPOSER ARRANGER EDUCATOR BANDLEADER: Spheres Of Influence Unsung Heroes Project The Brian Lynch Quartet Brian Lynch "This is a new millennium, and a lot of music has gone down," Brian Lynch said several years ago. "I think that to be a jazz musician now means drawing on a wider variety of things than 30 or 40 years ago. Not to play a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but to blend everything together into something that has integrity and sounds good. Not to sound like a pastiche or shifting styles; but like someone with a lot of range and understanding." Trumpeter and Grammy© Award Winner Brian Lynch brings to his music an unparalleled depth and breadth of experience. -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

Historic Structures

Historic structures significant structures of the past Figure 1: Illustration of cross-sectional and perspective views of the Kahn reinforcement bar, along with a diagram of the theoretical “truss action”. ® t the time of this writing, a vacant A recent survey of the area identified buildings former bakery is standing for a few that are potentially historic. A low-rise structure more days at the corner of Fifth Street without any prominent architectural features, North and Seventh Avenue North, a series of mismatched additions, and a leak- Ajust outside of the official boundary of the local ing roof Copyrightmight typically and national historic Warehouse District of be dismissed. However, Minneapolis, Minnesota. The building is typi- a 1909 building permit cal of others in the area: a one- to three-story card for the bakery noted The Kahn System of utilitarian structure with little architectural orna- that the “fireproof Kahn Reinforced Concrete mentation and several additions. The hodgepodge concrete tile system” was of construction styles is reflected by the variety used in the building’s early of structural systems found within, including construction. Furthermore, the bakery is purport- Why it Almost Mattered load-bearing masonry walls, cast iron columns, edly the site of the invention of “sliced bread” and framing of heavy timber, structural steel and and other innovations in the baking industry. By Ryan Salmon, EIT and reinforced concrete; the building is a dictionary of Thus, when a proposal for a new apartment Meghan Elliott, P.E., Associate AIA historic construction techniques. It is a familiar magazinebuilding suggested demolition of the bakery, the scene in many urban industrialS areas: T declining R Minneapolis U Heritage C Preservation T CommissionU R E industries leave behind a decaying infrastructure was charged with making the decision as to and abandoned buildings. -

Steppin' Out, Steppin' Forward

Ralph Lalama: Steppin' Out, Steppin' Forward Ralph Lalama's rich tenor saxophone voice has been heard for years on the New York City scene, perhaps most notably with the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra and its predecessors, first led by Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, and later by just Lewis. He's a guy who grew up when rock music was fully bursting on the American scene, but maintains that not much of that music touched him. He came from a family that listened to jazz and the American Popular Song canon, and he chose that direction. "The feeling of it," is the turnon of jazz to the Pennsylvania native who has called the Big Apple area his home for several years now. He's not native, but he's a New Yorker, alright. He's got the style of speech, a kind of dry New York Italian sense of humor and a whatmeworry casualness about him. "I love the beat. I'm a beat guy. And I love the interactionthe conversation on the bandstand, musically, of course. I think the U.S. Senate could learn a lot if they just listened to jazz sometime. They really should." "Some corporations do. They present jazz to their corporations, to show how to get camaraderie and listening to each other and know what everybody else is doing, to make a whole. A couple guys told me this happens. I think Congress should get into it, instead of listening to Bruce Springsteen," he adds with an exaggerated "steeeen" in a semigruff but amiable manner. -

Hr1047 Enr.Pdf

ENROLLED HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 1047 By: Shumate, Adkins, Armes, Askins, Auffet, Balkman, Banz, Benge, Billy, Bingman, Blackburn, Blackwell, Braddock, Brannon, Brown, Calvey, Carey, Cargill, Case, Coody, Cooksey, Covey, Cox, Dank, Denney, DePue, Deutschendorf, DeWitt, Dorman, Duncan, Eddins, Ellis, Gilbert, Glenn, Hamilton, Harrison, Hastings, Hickman, Hiett, Hilliard, Hyman, Ingmire, Jackson, Jett, Johnson, Jones, Kern, Kiesel, Lamons, Liebmann, Lindley, Liotta, Martin, Mass, McCarter, McDaniel, McMullen, McPeak, Miller (Doug), Miller (Ken), Miller (Ray), Morgan (Danny), Morgan (Fred), Morrissette, Nance, Nations, Newport, Perry, Peters, Peterson (Pam), Peterson (Ron), Piatt, Plunk, Pruett, Reynolds, Richardson, Roan, Roggow, Rousselot, Shelton, Sherrer, Shoemake, Smaligo, Smithson, Staggs, Steele, Sullivan, Sweeden, Terrill, Thompson, Tibbs, Toure, Trebilcock, Turner, Walker, Wesselhoft, Wilt, Winchester, Worthen, Wright and Young A Resolution honoring the 2005 inductees into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame; and directing distribution. WHEREAS, Lifetime Achievement Award Winner Nat “King” Cole was born Nathaniel Adams Coles in 1917. At four he moved to Chicago when his father was called to the True Light Baptist Church. Even at that age he could sing "Yes, We Have No Bananas" as he accompanied himself on the piano. His first public performance as a pianist was at four in Chicago's Regal Theater. His mother, who was his first music teacher, wanted him to become a classical pianist; and WHEREAS, Cole was the first African-American jazz musician to have his own weekly radio show (1948-49). In 1956, he became the first African American to have a weekly program on network television (1956-57), but the show was canceled because it could not find a national sponsor. -

Scripps Institution of Oceanography Uni Versity of California, San Diego La Jolla, California

SCRIPPS INSTITUTION OF OCEANOGRAPHY UNI VERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA The George H. Scripps Memorial Marine Biological Laboratory of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego George G. Shor, Jr. Elizabeth N. Shor Fred N. Spiess Historic structure Report to the California Office of Historic Preservation SIO Reference 79-26 October 1979 'Ihis report was originally submitted in June 1979 as a manuscript to the California state Office of Historic Preservation. It was printed in October 1979, with minor changes in the text and with more significant changes on page 39. based on information that was uncovered during the summer of 1979 by volunteers who enthusiastically removed interior modifications of the building that had been made over many years. Cover drawing by Helen Reynolds TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY 1 PLANNING, DESIGN, AND CONSTRUCTION 3 Acquiring the Land 3 Planning the Building 7 The Architect 8 The Engineer 9 Construction History 11 CHANGES AFTER CONSTRUCTION 24 THE CO}IDITION OF THE BUILDING IN JUNE, 1979 29 GEORGE H. SCRIPPS LABORATORY -- AS ART I~O Acknowledgments 41 About the Authors 41 Notes and References Appendix i List of Figures 1, Kahn reinforcement, of types used in Scripps Laboratory 12 2. Exterior view of George H. Scripps Memorial Laboratory, about 1911 15 3. Ground floor plan of the laboratory in 1912 16 4. Second floor plan of the laboratory in 1912 17 5. View of one corner of the library, about 1912 22 6. Plans by Francis B. Sumner for changes to be made in 1932 25 7. -

The George H. Scripps Memorial Marine Biological Laboratory of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego

SCRIPPS INSTITUTION OF OCEANOGRAPHY UNI VERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA The George H. Scripps Memorial Marine Biological Laboratory of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego George G. Shor, Jr. Elizabeth N. Shor Fred N. Spiess Historic structure Report to the California Office of Historic Preservation SIO Reference 79-26 October 1979 'Ihis report was originally submitted in June 1979 as a manuscript to the California state Office of Historic Preservation. It was printed in October 1979, with minor changes in the text and with more significant changes on page 39. based on information that was uncovered during the summer of 1979 by volunteers who enthusiastically removed interior modifications of the building that had been made over many years. Cover drawing by Helen Reynolds TABLE OF CONTENTS BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PROPERTY 1 PLANNING, DESIGN, AND CONSTRUCTION 3 Acquiring the Land 3 Planning the Building 7 The Architect 8 The Engineer 9 Construction History 11 CHANGES AFTER CONSTRUCTION 24 THE CO}IDITION OF THE BUILDING IN JUNE, 1979 29 GEORGE H. SCRIPPS LABORATORY -- AS ART I~O Acknowledgments 41 About the Authors 41 Notes and References Appendix i List of Figures 1, Kahn reinforcement, of types used in Scripps Laboratory 12 2. Exterior view of George H. Scripps Memorial Laboratory, about 1911 15 3. Ground floor plan of the laboratory in 1912 16 4. Second floor plan of the laboratory in 1912 17 5. View of one corner of the library, about 1912 22 6. Plans by Francis B. Sumner for changes to be made in 1932 25 7. -

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 3, May 2, 1988 Writer & Editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-Ordinator ______

NATIONAL JAZZ CO-ORDINATION NEWSLETTER No 3, May 2, 1988 Writer & editor: Eric Myers, National Jazz Co-ordinator ________________________________________________________ Visit of the Australian Jazz Orchestra to the United States. In a two-weeks visit to the United States, from April 5-19, the AJO played to open-air audiences for three days at the Houston International Festival, in jazz clubs for one night in Chicago (The Jazz Showcase), San Francisco (Kimball's) and Los Angeles (Catalina Bar & Grill), in a New York jazz club (Carlos I) for three nights, and to a concert hall audience of over 400 at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. A shot of the Australian Jazz Orchestra, which appeared in The Australian newspaper on December 11, 1987. Four musicians at the back are L-R, James Morrison, Paul Grabowsky, Dale Barlow, Bernie McGann. Middle row, L-R, Gary Costello, Doug DeVries, Bob Venier, Bob Bertles, Alan Turnbull, Don Burrows, Warwick Alder. Front row, crouching, L-R, Peter Brendlé, Eric Myers. This does not include the trombonist Dave Panichi who joined the band for the US tour… PHOTO CREDIT BRANCO GAICA 1 The band included 12 musicians: Warwick Alder (trt & flugel), Bob Venier (trt & flugel), James Morrison (tromb, trt, tuba & euphonium), Dave Panichi (tromb & flugbn), Bob Bertles (alto, baritone & flute), Bernie McGann (alto), Dale Barlow (sop & tenor), Don Burrows (flutes & baritone), Paul Grabowsky (pno), Doug de Vries (gtr), Gary Costello (bass) and Alan Turnbull (drs). Trombonist Dave Panichi, who joined the AJO for the US tour… As I was able to hear every performance of the AJO in the US, I can vouch for the fact that the band played with absolute brilliance; the players generally played longer solos than they did with the AJO in Australia, and pushed themselves way beyond their normal limits. -

Flint Municipal Center, Flint

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _City of Flint Municipal Center______________________________ Other names/site number: _Flint Civic Center _________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing __________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _1101 Saginaw Street, 210 East Fifth Street, 310 East Fifth Street_ City or town: _Flint________ State: __MI________ County: _Genesee______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering