“Refugee City”: Between Global Human Rights and Community Self Regulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Bank and Gaza 2020 Human Rights Report

WEST BANK AND GAZA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Palestinian Authority basic law provides for an elected president and legislative council. There have been no national elections in the West Bank and Gaza since 2006. President Mahmoud Abbas has remained in office despite the expiration of his four-year term in 2009. The Palestinian Legislative Council has not functioned since 2007, and in 2018 the Palestinian Authority dissolved the Constitutional Court. In September 2019 and again in September, President Abbas called for the Palestinian Authority to organize elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council within six months, but elections had not taken place as of the end of the year. The Palestinian Authority head of government is Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh. President Abbas is also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and general commander of the Fatah movement. Six Palestinian Authority security forces agencies operate in parts of the West Bank. Several are under Palestinian Authority Ministry of Interior operational control and follow the prime minister’s guidance. The Palestinian Civil Police have primary responsibility for civil and community policing. The National Security Force conducts gendarmerie-style security operations in circumstances that exceed the capabilities of the civil police. The Military Intelligence Agency handles intelligence and criminal matters involving Palestinian Authority security forces personnel, including accusations of abuse and corruption. The General Intelligence Service is responsible for external intelligence gathering and operations. The Preventive Security Organization is responsible for internal intelligence gathering and investigations related to internal security cases, including political dissent. The Presidential Guard protects facilities and provides dignitary protection. -

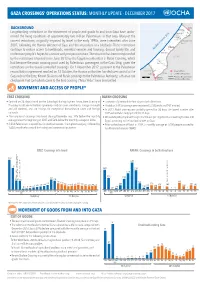

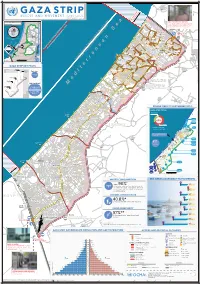

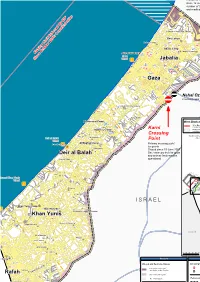

Gaza Crossings' Operations Status: Monthly

GAZA CROSSINGS’ OPERATIONS STATUS: MONTHLY UPDATE - DECEMBER 2017 BACKGROUND Erez Beit Lahiya ¹ ! Longstanding restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from Gaza have under- ! Jabalya ! Beit Hanoun mined the living conditions of approximately two million Palestinians in that area. Many of the Gaza City ! n Sea ! Ash Shuja’iyeh current restrictions, originally imposed by Israel in the early 1990s, were intensified after June anea Nahal Oz Karni 2007, following the Hamas takeover of Gaza and the imposition of a blockade. These restrictions iterr GAZA Med 21 continue to reduce access to livelihoods, essential services and housing, disrupt family life, and 30! 0 undermine people’s hopes for a secure and prosperous future. The situation has been compounded Deir al B alah by the restrictions imposed since June 2013 by the Egyptian authorities at Rafah Crossing, which ISRAEL ! had become the main crossing point used by Palestinian passengers in the Gaza Strip, given the Khan Yunis Khuza’a ! restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. On 1 November 2017, pursuant to the Palestinian 14389 Rafah EGYPT ! Crossing Point reconciliation agreement reached on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Sufa Rafah¹º» Closed Crossing Point Armistice Declaration Line Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority; a Hamas-run 5 Km ¹º» Kerem checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing (“Arba’ Arba’”) was dismantled. Shalom International Boundary MOVEMENT AND ACCESS OF PEOPLE* EREZ CROSSING RAFAH CROSSING • Opened on 26 days (closed on five Saturdays) during daytime hours, from Sunday to • Exceptionally opened for four days in both directions. -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

The Earless Children of the Stone

REFUGEE PARTICIPATION NETWORK 7 nvxi February 1990 Published by Refugee Studies Programme, Queen Elizabeth House, 21 St Giles, OXFORD OX1 3LA, UK. THE EARLESS CHILDREN OF THE STONE ££££ ;0Uli: lil Sr«iiKKiJi3'^?liU^iQ^^:;fv'-' » <y * C''l* I WW 'tli' (Cbl UUrHfill'i $ J ?ttoiy#j illCiXSa * •Illl •l A Palestinian Mother of Fifteen Children: 7 nave fen sons, eacn wi// nave ten more so one hundred will throw stones' * No copyright. MENTAL HEALTH CONTENTS THE INTIFADA: SOME PSYCHOLOGICAL Mental Health 2 CONSEQUENCES * The Intifada: Some Psychological Consequences * The Fearless Children of the Stone The End of Ramadan * Testimony and Psychotherapy: a Reply to Buus and Agger riday was a busy day in the town of Gaza, with many people F out in the streets buying food in preparation for the celebration ending Ramadan. The unified Leadership of Palestine Refugee Voices from Indochina 8 had issued a clandestine decree that shops could stay open until 5 * Forced or Voluntary Repatriation? p.m., and that people should stay calm during the day of the feast. * What is it Like to be a Refugee in They were not to throw stones at the soldiers while Site 2 Refugee Camp on the demonstrating. On their side, the Israeli authorities were said to have promised to keep their soldiers away from the refugee Thai-Cambodian Border? camps. Later, the matron of Al Ahli Arab general hospital * Some Conversations from Site 2 confessed that she had nonetheless kept her staff on full alert. Camp * Return to Vietnam In the early morning of Saturday, 6 May we awoke to cracks of gunfire and the rumble of low flying helicopters. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

Shelter 2014 A3 V1 Majed.Pdf (English)

GAZA STRIP: Geographic distribution of shelters 21 July 2014 ¥ 3km buffer Zikim a 162km2 (44% of GaKazrmaiya area) 100,000 poeple internally displaced e Estimated pop. of 300,000 B?4 84,000 taking shelter in UNRWA schools S Yad Mordekhai n F As-Siafa B?4 B?34 Governorate # of IDPs a ID y d e e e h b s a R Netiv ha-Asara Gaza 3 2,401 l- n d A e a c Erez Crossing KhanYunis 9 ,900 r Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) r (Umm An-Naser) fo 4 º» r h ¹ a n 1 al n Middle 7 ,200 S ee 0 l-D e E 2 E t Beit Lahiya 'Izbat Beit Hanoun a t i k k y E a e l- j S North 2 1,986 l B lo l- i a a A m h F a - 34 i u r l B? J A 5! 5! 5! d L t 'Arab Maslakh Madinat al 'Awda i S w Rafah 1 2,717 ta 5! Beit Lahiya r af 5! ! ee g 5! S 5 az Ash Shati' Camp l- 5! W Beit Hanoun e A !5! Al- n 5!5! 5 lil 5!5! Al-q ka ha i uds ek K 5! l-S Grand Total 8 4,204 M h 5!Jabalia A s 5!5! Jabalia Camp i 5!5! D S !x 5!5!5! a a r le a d h Source of data: UNRWA F o m n a 5!5! a r a K J l- a E m l a a l A n b 5! a 5!de Q 5! l l- d N A Gaza e as e e h r s City a R l- A 5!5! 5! 5! s d ! Mefalsim u 5! Q ! 5! l- 5 A 5! A l- M o n a t 232 kk a B? e r l-S A Kfar Aza d a o R l ta s a o C Sa'ad Al Mughraqa arim Nitz ni - (Abu Middein) Kar ka ek n ú S ú 5! e b l- B a A r tt Juhor ad Dik a a m h K O l- ú A ú Alumim An Nuseirat Shuva Camp 5! 5! Zimrat B?25 5! 5! 5! I S R A E L n e e 5! Kfar Maimon D a 5! - k Tushiya l k Al Bureij Camp E e Az Zawayda h S la l- a A S 5! Be'eri !x 5! Deir al Balah Al Maghazi Shokeda Camp 5! 5! Deir al Balah 5!5! Camp Al Musaddar d a o f R la k l a o ta h o 232 -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

The Meaning of Homeland for the Palestinian Diaspora : Revival and Transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï

The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora : revival and transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï To cite this version: Mohamed Kamel Doraï. The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora : revival and trans- formation. Al-Ali, Nadje Sadig ; Koser, Khalid. New approaches to migration ? : transnational com- munities and the transformation of home, Routledge, pp.87-95, 2002. halshs-00291750 HAL Id: halshs-00291750 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00291750 Submitted on 24 Sep 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora Revival and transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï Lost partially in 1948, and complete1y in 1967, the idea of a homeland continues to live in Palestinian social practices and through the construction of a diasporic territory - a symbolic substitute for the lost homeland. This chapter aims to analyse the mechanisms by which the homeland has been perpetuated in exile, and focuses in particular on Palestinian refugee camps and settlements. It shows how a refugee community can partially transform itself into a transnational community, and examines what role the transformation of home plays in this process. After fifty years of exile, Palestinian refugees continue to claim their right to return to their country of origin. -

Bringing Back the Palestinian Refugee Question

Bringing Back the Palestinian Refugee Question Middle East Report N°156 | 9 October 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Palestinian Refugee Question and the Two-state Solution ...................................... 5 A. Palestinian Perspectives: Before Oslo ....................................................................... 5 B. Palestinian Perspectives: After Oslo .......................................................................... 7 C. The Refugee Question in Negotiations ...................................................................... 10 1. Official Palestinian positions................................................................................ 10 2. The chasm: leadership, people and refugees ....................................................... 15 III. Palestinian Refugees: Perspectives and Concerns ........................................................... 19 A. Camp Governance ...................................................................................................... 19 B. Political and Social Marginalisation .......................................................................... 23 C. -

23 November 2020

3 - 23 November 2020 Latest development (outside the reporting period) On 25 November, citing the lack of building permits, the Israeli authorities demolished 11 Palestinian-owned structures in the Massafer Yatta area of southern Hebron. These included homes, livelihood-related structures and water and sanitation facilities, some of which had been previously provided as humanitarian assistance. Twenty-five people were displaced and over 700 were otherwise affected. All but one of the seven communities targeted are located in an area designated closed for military training, and are at risk of a forcible transfer. This report exceptionally covers three weeks; the next issue will be released on 10 December, covering the normal two-week period. During the reporting period (3-23 November), a total of 129 structures were demolished, or seized, due to a lack of Israeli-issued building permits, displacing 100 people and otherwise affecting at least 200. The largest incident took place on 3 November in , where 83 structures were destroyed, displacing 73 people, including 41 children. Thirty more structures were demolished in 12 other Area C communities. The remaining 16 took place in East Jerusalem, where demolitions have resumed after a three-week suspension, following an announcement by the Israeli authorities on 1 October that, due to the pandemic, they would stop the demolition of inhabited residential buildings in the city. More structures have been demolished or seized so far in 2020, than in any complete year since OCHA began systematically documenting this practice in 2009, with the exception of 2016. On 4 November, Israeli forces shot and killed an off-duty member of the Palestinian security forces at a checkpoint south of Nablus city, reportedly after he opened fire at soldiers. -

POSITION PAPER- Palesinian Refugees

The Question of Palestine in the times of COVID-19: Position paper on the situation for Palestinian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and Syria (No.2) June 2020 This position paper is part of a series that the Global Network of Experts on the Question of Palestine (GNQP) is producing to document the impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) on the Question of Palestine, by studying the effect of the pandemic on Palestinian refugees in the region. This brief focuses on Palestinian refugees residing in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and Syria. Purpose of the brief approximately 5.6 million are registered The brief shows how the COVID-19 as “Palestine refugees” with the United crisis is affecting Palestinian refugees Nations Relief and Works Agency for in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine Palestinians in the Near East (UNRWA) in (Gaza Strip and West Bank, including East Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and 2 Jerusalem) and Syria. Following a general Syria. A smaller number was displaced background, the paper presents: when Israel occupied the Gaza Strip and West Bank, including East Jerusalem · a summary of available regional in 1967; while these are not officially and country-specific facts that registered with UNRWA, some receive its indicate that COVID-19 is aggravating services on humanitarian grounds. Less the humanitarian conditions and than half of these refugees, including vulnerability of Palestinian refugees; their descendants, live in one of the 58 · a brief overview of applicable legal recognized refugee camps, while an obligations toward Palestinian unknown number live in urban and rural refugees; (camp) settings across the region.