Bears in Pakistan: Distribution, Population Biology and Human Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2017 Vol

International Bear News Tri-Annual Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group Fall 2017 Vol. 26 no. 3 Sun bear. (Photo: Free the Bears) Read about the first Sun Bear Symposium that took place in Malaysia on pages 34-35. IBA website: www.bearbiology.org Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL BEAR NEWS 3 International Bear News, ISSN #1064-1564 MANAGER’S CORNER IBA PRESIDENT/IUCN BSG CO-CHAIRS 4 President’s Column 29 A Discussion of Black Bear Management 5 The World’s Least Known Bear Species Gets 30 People are Building a Better Bear Trap its Day in the Sun 33 Florida Provides over $1 million in Incentive 7 Do You Have a Paper on Sun Bears in Your Grants to Reduce Human-Bear Conflicts Head? WORKSHOP REPORTS IBA GRANTS PROGRAM NEWS 34 Shining a Light on Sun Bears 8 Learning About Bears - An Experience and Exchange Opportunity in Sweden WORKSHOP ANNOUNCEMENTS 10 Spectacled Bears of the Dry Tropical Forest 36 5th International Human-Bear Conflict in North-Western Peru Workshop 12 IBA Experience and Exchange Grant Report: 36 13th Western Black Bear Workshop Sun Bear Research in Malaysia CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENTS CONSERVATION 37 26th International Conference on Bear 14 Revival of Handicraft Aides Survey for Research & Management Asiatic Black Bear Corridors in Hormozgan Province, Iran STUDENT FORUM 16 The Andean Bear in Manu Biosphere 38 Truman Listserv and Facebook Page Reserve, Rival or Ally for Communities? 39 Post-Conference Homework for Students HUMAN BEAR CONFLICTS PUBLICATIONS -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Chitral Audit Year 2016

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT CHITRAL AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................. ii Preface ................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... v SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ................................................................... viii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ................................................................................................. viii Table 2: Audit observations Classified by Categories (Rs in million) ...................................... viii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................................ ix Table 4: Table of Irregularities pointed out ................................................................................. x Table 5: Cost Benefit Ratio ......................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 District Government Chitral ......................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Report on Evaluation of Empowerment of Women in District Mansehra Through Women Friendly Halls

Report on Evaluation of Empowerment of Women in District Mansehra through Women Friendly Halls Sidra Fatima Minhas 11/27/2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 4 1. Women Freindly Halls (WFH) ......................................................................................... 5 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 8 1.1.1 Geographical Background ................................................................................ 9 1.1.2 Socio Cultural Context .....................................................................................12 1.1.3 Women Friendly Halls Project .........................................................................12 1.1.4 Objectives of WFHs Project ............................................................................13 1.2 Presence and Activities of Other Players ................................................................14 1.3 Rationale of the Evaluation .....................................................................................15 1.3.1 Objectives and Aim of the Evaluation ..............................................................15 1.4 Scope of the Evaluation .........................................................................................16 1.4.1 Period and Course of Evaluation .....................................................................16 1.4.2 Geographical -

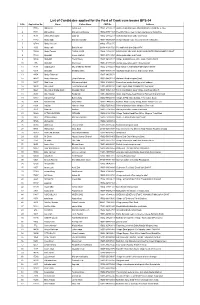

List of Candidates Applied for the Post of Cook-Cum-Bearer BPS-04 S.No Application No

List of Candidates applied for the Post of Cook-cum-bearer BPS-04 S.No Application No. Name Father Name CNIC No. Address 1 17715 Abbas Ali Akbar Gul 17301-2133451-1 Shaheen Muslim town, Mohallah Nazer Abad No 2, Hou 2 17171 Abbas khan Muhammad Sarwar 15602-0357410-5 The City School near to wali swat palace Saidu,Sha 3 7635 abbas khan zafar zafar ali 15602-2565421-7 mohalla haji abad saidu sharif swat 4 11483 Abdul aziz Muhammad jalal 15601-4595672-7 village baidara moh: school area teh:matta dist : 5 12789 Abdul Haleem - 90402-3773217-5 - 6 3090 Abdul Jalil Bakht Munir 21104-4193372-9 P/o and tehsil khar Bajur KPK 7 15909 Abdul Tawab FAZAL AHAD 15602-1353439-1 NAWAKALY MUHALA QANI ABADAN TEHSIL BABOZAY SWAT 8 17442 Abdullah Aleem bakhsh 15607-0374932-1 Afsar abad saidu sharif swat 9 10806 Abdullah Fazal Raziq 15607-0409351-5 Village Gulbandai p.o office saidu sharif tehsil b 10 255 Abdullah Mehmood 15602-6117033-5 Jawad super store panr mingora swat 11 7698 ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD IKRAM 15602-2135660-7 MOH BACHA AMANKOT MINGORA SWAT 12 4215 Abdullah Sarfaraz khan 15607-0359153-1 Almadina Model School and College Swat 13 4454 Abdur Rahman - 15607-0430767-1 - 14 14147 Abdur Rahman Umar Rahman 15602-0449712-7 Rahman Abad mingora Swat 15 12477 Abid khan Muhammad iqbal 15602-2165882-7 khunacham saidu sharif po tehsil babuxai 16 14428 Abu Bakar Tela Muhammad 17301-6936018-1 Ghari Inayat Abad Gulbahar # 2 Peshawar 17 10621 Abu Bakar Sadiq Shah Muqadar Shah 15607-0352136-7 Tehsil and District Swat Village and Post office R 18 9436 Abu Bakkar Barkat Ali 15607-0443898-5 Ikram Cap House Near Kashmir Backers Nishat Chowk 19 13113 Adnan Khan Bakht Zada 15602-9084073-3 Village & P/O: Bara Bandai, Teh: Kabal ,Swat. -

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011)

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - Daily Flood Report Date (29 09 2011) SWAT RIVER Boundary 14000 Out Flow (Cusecs) 12000 International 10000 8000 1 3 5 Provincial/FATA 6000 2 1 0 8 7 0 4000 7 2 4 0 0 2 0 3 6 2000 5 District/Agency 4 4 Chitral 0 Gilgit-Baltistan )" Gauge Location r ive Swat River l R itra Ch Kabul River Indus River KABUL RIVER 12000 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Kurram River 10000 Out Flow (Cusecs) Kohistan 8000 Swat 0 Dir Upper Nelam River 0 0 Afghanistan 6000 r 2 0 e 0 v 0 i 1 9 4000 4 6 0 R # 9 9 5 2 2 3 6 a Dam r 3 1 3 7 0 7 3 2000 o 0 0 4 3 7 3 1 1 1 k j n ") $1 0 a Headworks P r e iv Shangla Dir L")ower R t a ¥ Barrage w Battagram S " Man")sehra Lake ") r $1 Amandara e v Palai i R Malakand # r r i e a n Buner iv h J a R n ") i p n Munda n l a u Disputed Areas a r d i S K i K ") K INDUS RIVER $1 h Mardan ia ") ") 100000 li ") Warsak Adezai ") Tarbela Out Flow (Cusecs) ") 80000 ") C")harsada # ") # Map Doc Name: 0 Naguman ") ") Swabi Abbottabad 60000 0 0 Budni ") Haripur iMMAP_PAK_KP Daily Flood Report_v01_29092011 0 0 ") 2 #Ghazi 1 40000 3 Peshawar Kabal River 9 ") r 5 wa 0 0 7 4 7 Kh 6 7 1 6 a 20000 ar Nowshera ") Khanpur r Creation Date: 29-09-2011 6 4 5 4 5 B e Riv AJK ro Projection/Datum: GCS_WGS_1984/ D_WGS_1984 0 Ghazi 2 ") #Ha # Web Resources: http://www.immap.org Isamabad Nominal Scale at A4 paper size: 1:3,500,000 #") FATA r 0 25 50 100 Kilometers Tanda e iv Kohat Kohat Toi R s Hangu u d ") In K ai Map data source(s): tu Riv ") er Punjab Hydrology Irrigation Division Peshawar Gov: KP Kurram Garhi Karak Flood Cell , UNOCHA RIVER $1") Baran " Disclaimers: KURRAM RIVER G a m ") The designations employed and the presentation of b e ¥ Kalabagh 600 Bannu la material on this map do not imply the expression of any R K Out Flow (Cusecs) iv u e r opinion whatsoever on the part of the NDMA, PDMA or r ra m iMMAP concerning the legal status of any country, R ") iv ") e K territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 400 r h ") ia the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

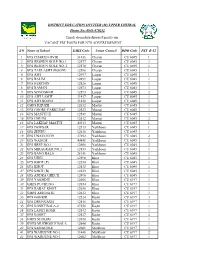

S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1

DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (M) UPPER CHITRAL Phone No: 0943-470252 Email: [email protected] VACANT PST POSTS FOR NTS ADVERTISEMENT S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1 GPS CHARUN OVIR 31436 Charun CU 6045 1 2 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO.1 12577 Charun CU 6045 1 3 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO..2 12578 Charun CU 6045 1 4 GPS TAKLASHT (BOONI) 12596 Charun CU 6045 1 5 GPS AWI 12497 Laspur CU 6045 1 6 GPS BALIM 12499 Laspur CU 6045 1 7 GPS HERCHIN 12526 Laspur CU 6045 1 8 GPS RAMAN 12573 Laspur CU 6045 1 9 GPS SONOGHUR 12593 Laspur CU 6045 2 10 GPS AWI LASHT 31437 Laspur CU 6045 1 11 GPS AWI BOONI 31438 Laspur CU 6045 1 12 GMPS KHUZH 12632 Mastuj CU 6045 1 13 GPS GHORU PARKUSAP 12523 Mastuj CU 6045 1 14 GPS MASTUJ II 12549 Mastuj CU 6045 1 15 GPS CHUINJ 12512 Mastuj CU 6045 2 16 GPS LAKHAP MASTUJ 40313 Mastuj CU 6045 1 17 GPS DEWSAR 12513 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 18 GPS ZHUPU 12610 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 19 GPS UNAVOUCH 37292 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 20 GPS WASUM 40841 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 21 GPS BREP NO.1 12508 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 22 GPS MIRAGRAM NO.2 12553 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 23 GPS BANG BALA 28141 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 24 GPS UJNU 12598 Khot CU 6045 1 25 GPS KHOT (P) 12534 Khot CU 6045 1 26 GPS KHOT 12532 Khot CU 6045 1 27 GPS KHOT (B) 12533 Khot CU 6045 1 28 GPS ANDRA GHECH 12496 Khot CU 6045 1 29 GPS YAKHDIZ 12606 Khot CU 6197 1 30 GMPS PUCHUNG 12654 Khot CU 6197 1 31 GPS RABAT KHOT 12656 Khot CU 6197 1 32 GMPS AMUNATE 12612 Khot CU 6197 1 33 GPS GOHKIR 12524 Kosht CU 6197 3 34 GPS DRUNGAGH 12516 Kosht CU 6197 1 35 GPS KOSHT BALA-2 27550 Kosht -

A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Madeeha Manzoor Center for Bioresource Research Adila Nazli Center for Bioresource Research, [email protected] Sabiha Shamim Center for Bioresource Research Fida Muhammad Khan Center for Bioresource Research Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Manzoor, M., Nazli, A., Shamim, S., & Khan, F. M. (2017). A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts, Journal of Bioresource Management, 4 (1). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.7102.0067 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: May 29, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Erratum Added the complete list of author names © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without appropriately and conspicuously citing the original work and source or Journal of Bioresource Management’s prior written permission. -

Assessment of Spatial and Temporal Flow Variability of the Indus River

resources Article Assessment of Spatial and Temporal Flow Variability of the Indus River Muhammad Arfan 1,* , Jewell Lund 2, Daniyal Hassan 3 , Maaz Saleem 1 and Aftab Ahmad 1 1 USPCAS-W, MUET Sindh, Jamshoro 76090, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Geography, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +92-346770908 or +1-801-815-1679 Received: 26 April 2019; Accepted: 29 May 2019; Published: 31 May 2019 Abstract: Considerable controversy exists among researchers over the behavior of glaciers in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) with regard to climate change. Glacier monitoring studies using the Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing techniques have given rise to contradictory results for various reasons. This uncertain situation deserves a thorough examination of the statistical trends of temperature and streamflow at several gauging stations, rather than relying solely on climate projections. Planning for equitable distribution of water among provinces in Pakistan requires accurate estimation of future water resources under changing flow regimes. Due to climate change, hydrological parameters are changing significantly; consequently the pattern of flows are changing. The present study assesses spatial and temporal flow variability and identifies drought and flood periods using flow data from the Indus River. Trends and variations in river flows were investigated by applying the Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s method. We divide the annual water cycle into two six-month and four three-month seasons based on the local water cycle pattern. -

Current Scenario and Threats to Ichthyo-Diversity in the Foothills of Hindu Kush: Addition to the Checklist of Coldwater Fishes of Pakistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 48(1), pp. 285-288, 2016. Short Communication Current Scenario and Threats to Ichthyo-Diversity in the Foothills of Hindu Kush: Addition to the Checklist of Coldwater Fishes of Pakistan Arif Jan,* Abdul Rab, Rooh Ullah, Hussain Shah, Haroon, Iftikhar Ahmad, Muhammad Younas and Ikram Ullah Department of Zoology, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal, Dir Upper. Article Information Received 16 January 2015 A B S T R A C T Revised 9 August 2015 Accepted 19 September 2015 Chitral, the pinnacle of Hindu Kush, draining 31 notable glaciers, is least studied for Ichthyo-faunal Available online 1 January 2016 diversity. This work explored the fish fauna and the risk factors for the Ichthyo-faunal diversity loss Authors’ Contributions at the foothills of Hindu Kush. A total of 21 fish species were collected from different parts and AJ has conducted the field work, tributaries of River Chitral, from Shandur up to Arandu, extending to Afghanistan border. Our analyzed the data and wrote the collection reported 4 fish species for the first time from Pakistan, namely Acanthocobitis article. HS, H and IA helped in the uropthalmus, Lepidopygnosis typus, Horalabiosa palaniensis, Horalabiosa joshuai. One species field work arrangements. MY, RU namely Nangra robusta is reported for the first time from River Chitral. Alluvial nature of rocks, and IU helped in literature search. construction of hydro projects and duck ponds, introduction of exotic species, erosion and AR helped in identification. sedimentation of rivers and streams, illegal fishing, and effluent discharges are the major concerns. Major threats to biodiversity loss need to be addressed for proper conservation of biodiversity as a Key words whole and Ichthyo-diversity in particular. -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Aryans, Harvesters and Nomads (Thursday July 6 2.00 – 5.00) Convenor: Prof

PANEL: Aryans, Harvesters and Nomads (Thursday July 6 2.00 – 5.00) Convenor: Prof. Asko Parpola: Department of Asian & African Studies University of Helsinki Excavations at Parwak, Chitral • Pakistan. Ihsan Ali: Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP & Muhammad Zahir: Lecturer, Government College, Peshawar The Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP, under the supervision of Prof. (Dr.) Ihsan Ali, Director, Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of NWFP, Peshawar has completed the first ever excavations in Chitral at the site of Parwak. The team included Muhammad Zahir, Lecturer, Government College, Peshawar and graduates of the Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar. Chitral, known throughout the world for its culture, traditions and scenic beauty, has many archaeological sites. The sites mostly ranging from 1800 B.C. to the early 600 B.C, are popularly known as Gandhara Grave Culture. Though brief surveys and explorations were conducted in the area earlier, but no excavations were conducted. The site of Parwak was discovered by a team of Archaeologists from Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of NWFP and Boston University, USA in a survey conducted in June 2003 under the direction of Prof. (Dr.) Ihsan Ali and Dr. Rafique Mughal. The site is at about 110 km north east of Chitral, near the town of Buni, on the right bank of river Chitral and set in a beautiful environment. The site measures 121 x 84 meter, divided in to three mounds. On comparative basis, the site is datable to the beginning of 2nd millennium BC and represents a culture, commonly known as Gandhara Grave Culture of the Aryans, known through graves and grave goods. -

Survey of Ecotourism Potential in Pakistan's Biodiversity Project Area (Chitral and Northern Areas): Consultancy Report for IU

Survey of ecotourism potential in Pakistan’s biodiversity project area (Chitral and northern areas): Consultancy report for IUCN Pakistan John Mock and Kimberley O'Neil 1996 Keywords: conservation, development, biodiversity, ecotourism, trekking, environmental impacts, environmental degradation, deforestation, code of conduct, policies, Chitral, Pakistan. 1.0.0. Introduction In Pakistan, the National Tourism Policy and the National Conservation Strategy emphasize the crucial interdependence between tourism and the environment. Tourism has a significant impact upon the physical and social environment, while, at the same time, tourism's success depends on the continued well-being of the environment. Because the physical and social environment constitutes the resource base for tourism, tourism has a vested interest in conserving and strengthening this resource base. Hence, conserving and strengthening biodiversity can be said to hold the key to tourism's success. The interdependence between tourism and the environment is recognized worldwide. A recent survey by the Industry and Environment Office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/IE) shows that the resource most essential for the growth of tourism is the environment (UNEP 1995:7). Tourism is an environmentally-sensitive industry whose growth is dependent upon the quality of the environment. Tourism growth will cease when negative environmental effects diminish the tourism experience. By providing rural communities with the skills to manage the environment, the GEF/UNDP funded project "Maintaining Biodiversity in Pakistan with Rural Community Development" (Biodiversity Project), intends to involve local communities in tourism development. The Biodiversity Project also recognizes the potential need to involve private companies in the implementation of tourism plans (PC II:9).