Pre-Print Version. Published Online on April 2018, Following the Terms Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Z-Nation - EP 2XX - FULL PINK (10/10/15) 2

EPISODE 200 "PEACE OF MURPHY" Written by REDACTED Directed by REDACTED PRODUCTION DRAFT 08/01/15 FULL BLUE 08/05/15 The Asylum Los Angeles 45315 FADE IN: 1 EXT. COUNTRY ROAD - DAY 1 We open on a desolate stretch of back-road. The mid-day sun beats down. There’s no noise. No crickets chirping. Like most places in this world: dead and way too quiet. A RUSTED BILLBOARD casts a shadow across the sweltering tarmac. A cartoon bear warning visitors that “ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT FOREST FIRES”. Behind the billboard, in the distance - AN ATOMIC FIRE RAVAGES THE LANDSCAPE. SLOW FOOTSTEPS break the silence. A WOUNDED-MAN drags himself down the road. Blackened and burned: The clothes are literally falling from his back. He’s sick and desperate - A victim of radiation poisoning. The Wounded-Man reaches the shadow of the billboard before stumbling - And collapsing to his knees. He looks towards the sky. Coughs. WOUNDED-MAN Please. Somebody... Anybody? ANGLE ON: A VEHICLE APPROACHING FROM THE DISTANCE The man smiles, his prayers have been answered. WOUNDED-MAN (CONT’D) Oh God, stop. Please stop. He climbs to his feet with what strength he can muster and frantically waves his arms around. The Truck continues its approach - It’s not slowing down. He realizes - and DASHES to the side - just as the vehicle speeds past. SCREECH! - The Truck comes to a complete stop just past the billboard. Brake-lights shine. The truck reverses back towards the bewildered man. The driver side window rolls down, revealing the mans savior - MURPHY sitting at the wheel with ROBERTA riding shotgun. -

Zombies in Western Culture: a Twenty-First Century Crisis

JOHN VERVAEKE, CHRISTOPHER MASTROPIETRO AND FILIP MISCEVIC Zombies in Western Culture A Twenty-First Century Crisis To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/602 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Zombies in Western Culture A Twenty-First Century Crisis John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro, and Filip Miscevic https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro and Filip Miscevic. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: John Vervaeke, Christopher Mastropietro and Filip Miscevic, Zombies in Western Culture: A Twenty-First Century Crisis. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, http://dx.doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0113 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/602#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

DGA's 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lily Bedrossian August 25, 2015 (310) 289-5334 DGA’s 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals: Employer Hiring of Women Directors Shows Modest Improvement; Women and Minorities Continue to be Excluded In First-Time Hiring LOS ANGELES – The Directors Guild of America today released its annual report analyzing the ethnicity and gender of directors hired to direct primetime episodic television across broadcast, basic cable, premium cable, and high budget original content series made for the Internet. More than 3,900 episodes produced in the 2014- 2015 network television season and the 2014 cable television season from more than 270 scripted series were analyzed. The breakdown of those episodes by the gender and ethnicity of directors is as follows: Women directed 16% of all episodes, an increase from 14% the prior year. Minorities (male and female) directed 18% of all episodes, representing a 1% decrease over the prior year. Positive Trends The pie is getting bigger: There were 3,910 episodes in the 2014-2015 season -- a 10% increase in total episodes over the prior season’s 3,562 episodes. With that expansion came more directing jobs for women, who directed 620 total episodes representing a 22% year-over-year growth rate (women directed 509 episodes in the prior season), more than twice the 10% growth rate of total episodes. Additionally, the total number of individual women directors employed in episodic television grew 16% to 150 (up from 129 in the 2013-14 season). The DGA’s “Best Of” list – shows that hired women and minorities to direct at least 40% of episodes – increased 16% to 57 series (from 49 series in the 2013-14 season period). -

Is This Hidden Gem the Best Sci-Fi Series Ever? by Steve Sternberg

August 2021 #114 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ Is This Hidden Gem the Best Sci-Fi Series Ever? By Steve Sternberg There are so many sub-genres of science fiction, and so many excellent vastly different sci-fi movies and television series, that singling out any as “the best” seems silly. How can you compare stories featuring aliens (e.g., Falling Skies, Colony, Raised by Wolves) to fantasy (e.g., Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Game of Thrones, The Witcher), horror (e.g., American Horror Stories, Van Helsing, Servant), post-apocalyptic (e.g., The Walking Dead, The Last Ship, Z Nation), space operas (e.g., Battlestar Galactica, Babylon 5, The Expanse), super heroes (e.g., The Flash, Titans, Superman & Lois), alternate histories (Man in the High Castle, Watchmen, For All Mankind), cyberpunk (e.g., Dollhouse, Almost Human, Altered Carbon), dystopian futures (e.g., The Handmaid’s Tale, Westworld, Snowpiercer), parallel worlds (e.g., Sliders, Fringe, Counterpoint), time travel (e.g., Quantum Leap, Travelers, Outlander) the supernatural (e.g., X-Files, Supernatural, Stranger Things), or franchises (e.g., Star Trek, Star Wars, Stargate)? A Sternberg Report Sponsored Message The Sternberg Report ©2021 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ That said, Netflix’s mystery thriller, Dark, needs to be carved into the Mount Rushmore of science-fiction dramas. It’s the most meticulously well-crafted series I’ve ever seen. It can be as confounding as it is compelling, but when it’s over, you realize you’ve just seen a masterpiece. Dark is among the very best sci-fi series ever made, and is certainly the best one incorporating time travel. -

Bsfs-B50-Pocket-Program.Pdf

Anti-Harassment Policy Balticon and other BSFS events are dedicated to providing a comfortable and harassment-free environment for everyone. In order to offer a welcoming and safe space for everyone, please be respectful of all others. Do not use slurs or derogatory comments about a person, group or category of people. This could include comments based on characteristics such as (but not limited to) actual or perceived race, national origin, sex, gender, sexual orientation, physical appearance, age, religion, ability, family or marital status or socioeconomic class. Do not behave in a manner disrespectful to another individual. The complete text of the BSFS Anti-Harassment Policy is available at http://balticon.org/wp50/wp- content/uploads/2015/07/Harassment-Policy.pdf. Pet Policy No pets allowed in Balticon function space. Weapons Policy All weapons, including but not limited to all swords, knives and replicas, projectile weapons including nerf toys and waterguns, must be peace bonded by designated convention personnel immediately upon the purchase of the weapon from a dealer or entering the hotel. It is your responsibility to be aware of and follow all laws regarding the possession of weapons. No sparring will be permitted in the convention. Balticon reserves the right to hold any weapons in violation until the end of the con. Failure to comply with this policy may result in the confiscation of your badge. MasQuerade Costumers are excepted for the time spanning a half hour before the Masquerade to a half hour after the MasQuerade. HOURS OF OPERATION Hours of Operation Function Location Friday Saturday Sunday Monday 10 am to MD 5 pm 10 am 1 pm; 10 am Art Show Salons to to reopen to A and E 7:30 pm 8 pm for sales 2 pm 2:15 to 5 pm New Garden Art Auction 2 pm MD Salon D MD Salon Friday 2 pm through Monday 5 pm F Entrance See Convention Operations for Lost & Found, Con Ops is beside security issues, late-night registration, to locate a the specific Balticon staff person, access to locked elevators functions spaces, etc. -

Editor Shiran Amir on Rejecting Rejection

DECEMBER 3, 2018 Cutting SyFy: Editor Shiran Amir on Rejecting Rejection When talking about her career path, you get the immediate sense that rejection isn’t a “no” for Shiran. There’s never been an obstacle that’s kept her from living her dream. Shattering ceiling after glass ceiling, she makes her rise up through the ranks look like a piece of cake. However, her story is equal parts strategy and risk – and none of it was easy. After taking countless chances in her career, of which some aspiring editors don’t see the other side, she has continually pushed herself to move onward and upward. She’s been an assistant editor on Fear of the Walking Dead, The OA, and Outcast to name a few, and is now a full fledged editor of Z Nation’s fifth season, editing the 4th and 9th episodes of the zombie apocalypse show. She’s currently on the Editors Guild Board of Directors and is involved in the post-production community in Los Angeles. And she’s only 30 years old. Born and raised in New York until she was eight years old, her Israeli parents decided Shiran should grow up around her grandparents and family back in Israel. She was educated in a small suburb of Israel and studied theatre and media studies in high school. Using Adobe Premiere on the old computers in the school’s lab, she slowly fell in love with the art of editing. 1 “I realized when I was 16 that I wanted to be an editor, and I was fortunate to figure that out pretty early on.” (seen here behind the camera during her time in the Israeli army, but spent most of her time in front of a computer editing) After graduating from high school, Shiran, like all Israeli women, was required to serve in the Israeli army for two years. -

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Male Female Female Signatory Company Title Female + Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown % Unknown Unknown % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 40 North Productions, LLC Looming Tower, The 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Hulu ABC Signature Studios, Inc. SMILF 8 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime ABC Studios American Housewife 24 13 54% 9 38% 2 8% 11 46% 0 0% 2 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios BlacK-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 11 46% 3 13% 4 17% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Code BlacK 13 6 46% 7 54% 3 23% 2 15% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds 22 10 45% 12 55% 4 18% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios For The People 9 4 44% 5 56% 0 0% 2 22% 2 22% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 16 67% 8 33% 4 17% 3 13% 9 38% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grown-ish 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% Freeform ABC Studios How To Get Away With 15 11 73% 4 27% 2 13% 2 13% 7 47% 0 0% 0 0% ABC Murder ABC Studios Kevin (Probably) Saves the 15 6 40% 9 60% 2 13% 4 27% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC World ABC Studios Marvel's Agents of 22 11 50% 11 50% 5 23% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% ABC S.H.I.E.L.D. -

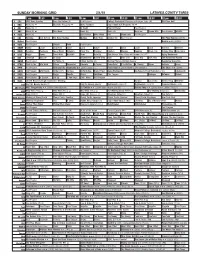

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

PRESS NOTES March 2019

PRESS NOTES March 2019 INFORMION 114 Minutes Ratio: 2:35 color Red Dragon DCP • AUDIO: 5.1 PRESS Emma Griffiths [email protected] PRODUCERS Larry Fessenden [email protected] Chadd Harbold [email protected] Jenn Wexler [email protected] PRINT TRAFFIC GLASS EYE PIX 172 East 4th Street #5F New York, NY 10009 WEBSITES A film by Larry Fessenden glasseyepix.com depravedfilm.com GLASS EYE PIX & FORAGER FILM COMPANY present DAVID CALL JOSHUA LEONARD and ALEX BREAUX "DEPRAVED" ANA KAYNE MARIA DIZZIA CHLOË LEVINE OWEN CampBELL and ADDISON TIMLIN cinematography CHRIS SKOTCHDOPOLE James SIEWERT production design APRIL LASKY costume design SARA ELISABETH LOTT makeup effects GERNER & SPEARS EFFECTS visual effects james SIEWERT music WILL bates sound design JOHN MOROS mix TOM EFINGER executive producers JOE SWANBERG EDWIN LINKER PETER GILBERT co-executive producerS andrew MER SIG DE MIGUEL STEPHEN VINCENT co-producer LIZZ ASTOR producers CHADD HARBOLD JENN WEXLER writer director editor producer LARRY FESSENDEN (c) 2019 DEPRAVED PRODUCTIONS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. A Glass Eye Pix COSTUME Lucy Double POST PICTURE "depRAVEd" Forager Film Company assistant costume designer ASHLEY MORGAN BLOOM Finishing Written and Performed by production ARIS BORDO Polidori Double CONTACT POST UNWANTED HOUSEGUEST wardrobe supervisor COLIN VAN WYE colorist publisher Tavistock Records CREW ALANNA GOODMAN Child Singers BLASE THEODORE BELLA MAGGIO "Wheels on the Bus" writer director editor Uniforms Edit and Online Facilities LARRY FESSENDEN KAUFMAN’S ARMY & NAVY JOEY MAGGIO THE STATION Performed by NIA AMALIA MOROS UNWANTED HOUSEGUEST producers additional animation LARRY FESSENDEN MAKEUP TV Voices BEN DUFF JAMES LE GROS "Pleasant Street" CHADD HARBOLD hair and makeup dept. -

Pryvtrsrch-1-Fight-The-Future-Online

Fight the Future THIS IS FULL OF SPIDERS... I mean, spoilers. Inside Logan The Future Composts The Past 6 Event Horizon Flags in Space 10 A Haunted House in Space 12 Pirates of the Caribbean & Event Horizon “Part of the ship, part of the crew.” 15 Avatar DeExtinction and Alienation in Space 16 Terminus A Positive Panspermia Tale 20 The Shannara Chronicles Setting the post-apocalyptic scene 24 Dark Matter & Killjoys The Future of Humanity in Space 27 Image Credits 31 Index 33 PRYVT.RSRCH - FIGHT THE FUTURE PRYVT.RSRCH - FIGHT THE FUTURE There are no sharks eating Marty McFly on Showing the autotrucks as “cabinless trucks” the sidewalk as in Back To The Future II’s recalls how cars were first presented as 1989 vision of 2015. horseless carriages. The Future Composts The Past It’s a gritty future, with passing references to Having their smarts in the undercarriage is Logan Logan isn’t a Sci-Fi, it’s a Western that just Grounding it as a progression from the happens to be set forward in time. Its setting present establishes that they’re in our world, more charismatic megafauna going extinct. an excellent rendering of fully automated is one of the many excellent characters in the not a sci-fi superhero universe full of marvels transport. This scene showed a future that’d film. Its design fiction elements just one of separate from that of mortal’s. Prosthetics are grafted on, requiring composted the past. the standout performances. maintenance and tweaking. These are Phones look the same as today. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research.