Advisory Visit River Elwy, Rhyl & St. Asaph Angling Association May 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

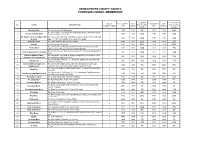

Proposed Arrangements Table

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St

Bodelwyddan, St Asaph Manor House Leisure Park Bodelwyddan, St. Asaph, Denbighshire, North Wales LL18 5UN Call Roy Kellett Caravans on 01745 350043 for more information or to view this holiday park Park Facilities Local Area Information Bar Launderette Manor House Leisure Park is a tranquil secluded haven nestled in the Restaurant Spa heart of North Wales. Set against the backdrop of the Faenol Fawr Hotel Pets allowed with beautiful stunning gardens, this architectural masterpiece will entice Swimming pool and captivate even the most discerning of critics. Sauna Public footpaths Manor house local town is the town of St Asaph which is nestled in the heart of Denbighshire, North Wales. It is bordered by Rhuddlan to the Locally north, Trefnant to the south, Tremeirchion to the south east and Shops Groesffordd Marli to the west. Nearby towns and villages include Bodelwyddan, Dyserth, Llannefydd, Trefnant, Rhyl, Denbigh, Abergele, Hospital Colwyn Bay and Llandudno. The river Elwy meanders through the town Public footpaths before joining with the river Clwyd just north of St Asaph. Golf course Close to Rhuddlan Town & Bodelwyddan Although a town, St Asaph is often regarded as a city, due to its cathe- Couple minutes drive from A55 dral. Most of the church, however, was built during Henry Tudor's time on the throne and was heavily restored during the 19th century. Today the Type of Park church is a quiet and peaceful place to visit, complete with attractive arched roofs and beautiful stained glass windows. Quiet, peaceful, get away from it all park Exclusive caravan park Grandchildren allowed Park Information Season: 10.5 month season Connection fee: POA Site fee: £2500 inc water Rates: POA Other Charges: Gas piped, Electric metered, water included Call today to view this holiday park. -

Birch House Business Centre Lon Parcwr Ruthin Ll15 1Na

29 Russell Road, Rhyl, Denbighshire, LL18 3BS Tel: 01745 330077 www.garethwilliams.co.uk Also as Beresford Adams Commercial 7 Grosvenor Street, Chester, CH1 2DD Tel: 01244 351212 www.bacommercial.com BIRCH HOUSE BUSINESS CENTRE LON PARCWR RUTHIN LL15 1NA TO LET Good quality office space 62.96 sq m (678 sq ft) Fully secured – 24/7 access Ample car parking LL15 1NA Flexible lease term Commercial & Industrial Agents, Development, Investment & Management Surveyors LOCATION of the Business Centre, external repairs and The well-established and successful Lon Parcwr property insurance. Business Park is excellently located just half a mile from the centre of this attractive market RATES town and administrative centre. The Business No rates are payable. Park stands alongside the town’s inner relief road connecting with major routes including SERVICES A525 (Rhyl, A55 Wrexham), A494 (Mold) and Mains water, electricity and drainage are A464 (Bala, Corwen and A5). The Park is thus connected to the building. The property is superbly positioned to service a wide heated and cooled by way of an air surrounding area. conditioning unit. Please refer to location plan. LEGAL COSTS Each party is responsible for payment of their DESCRIPTION own legal costs incurred in documenting this The available office suite is located at first floor transaction. within an established good quality Business Centre, being accessed via an impressive VAT shared entrance with tiled floor leading to All prices quoted are exclusive of but may be internal corridors providing access to a series liable to Value Added Tax. of office suites at ground and first floor level. -

Clwyd Flood Risk Management Strategy

Managing the risk of tidal flooding The tidal Clwyd Flood Risk Management Strategy is now complete What is the tidal Clwyd Flood Risk Manag ement Strategy? A flood risk management strategy is a 100 year plan that sets out how we should adapt, improve and generally prepare an area for dealing with flooding in the short term, medium term and long ter m. The tidal Clwyd strategy covers the north Wales coastline and inland tidal area between Abergele and the Denbighshire-Flintshire border near Prestatyn. It covers the main centres of population around Rhyl, Kinmel Bay and Prestatyn. In addition to the permanent residents living in the strategy area, many thousands of people visit the area each year, including holidaymakers at local caravan parks. The tidal Clwyd strategy recommends a solution to tackle both tidal flooding from the river and coastal flooding from the sea. The strategy will be reviewed regularly during its lifetime to take account of any changes that happen over time. What does the Strategy say? Our overarching strategy is that all properties in this area should be protected to their current standard or better, through a combination of improvements to existing flood defences in the short term, and by realigning embankments in the medium to long term to make space for water. The existing coastal defences will be maintained and improved in future as necessary. The strategy These ke y principles form the basis of our strategy for managing flood risk. A combin ation of technical work, environmental assessment and consultation with stakeholders and loca l people helped us decide on the best short, medium and long term solutions. -

Tourism, Culture and Countryside

TOURISM, CULTURE AND COUNTRYSIDE SERVICE PLAN Key Priorities and Improvements for 2009 – 2011 Directorate : Environment Service : Tourism Culture & Countryside Head of Service: Paul Murphy Lead Member : David Thomas 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Tourism, Culture and Countryside became part of the Environment Directorate on May 1 2008, moving across from the Lifelong Learning Directorate. The service is made up of the following :- Countryside Services – comprises an integrated team of different specialisms including: Biodiversity and Nature Conservation; Archaeology; Coed Cymru; Wardens, Countryside Recreation and Visitor Services; Heather and Hillforts; and manages the Clwydian Range Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), initiatives on Walking for Health, Open and Coastal Access, and owns and manages 2 Country Parks and a further 22 Countryside Sites. The Services’ work is wide-ranging, is both statutory and non-statutory in nature and involves partnerships with external agencies and organisations in most cases. The work of the Service within the Clwydian Range Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP) and Heather and Hillforts HLF project is a good example of the essential collaboration and the close co-ordination needed in our activities. The Countryside Council for Wales, as a key funding and work partner, also guide and influence our work through jointly set objectives and outcomes. Heritage Services – responsible for the management and development of the County's heritage provision including Nantclwyd y Dre, Plas Newydd, Llangollen; Rhyl Museum; Ruthin Gaol; and the Service’s museum store.Each venue has a wealth of material and is an ideal educational resource. The service also arranges exhibitions and works closely with local history and heritage organisations, and school groups. -

Dyffryn Clwyd Mission Area

Dyffryn Clwyd Mission Area Application Pack: November 2019 The Diocese of St Asaph In the Diocese of St Asaph or Teulu Asaph, we’re • Growing and encouraging the whole people of God • Enlivening and enriching worship • Engaging the world We’re a family of more than 7,000 regular worshippers, with 80 full time clergy, over 500 lay leaders, 216 churches and 51 church schools. We trace our history to the days of our namesake, St Asaph and his mentor, St Kentigern who it’s believed built a monastery in St Asaph in AD 560. Many of the churches across the Diocese were founded by the earliest saints in Wales who witnessed to Christian faith in Wales and have flourished through centuries of war, upheaval, reformation and reorganisation. Today, the Diocese of St Asaph carries forward that same Mission to share God’s love to all in 21th Century north east and mid Wales. We’re honoured to be a Christian presence in every community, to walk with people on the journey of life and to offer prayers to mark together the milestones of life. Unlocking our Potential is the focus of our response to share God’s love with people across north east and mid Wales. Unlocking our Potential is about bringing change, while remaining faithful to the life-giving message of Jesus. It’s about challenging, inspiring and equipping the whole people of God to grow in their faith. Geographically, the Diocese follows the English/Welsh border in the east, whilst the western edge is delineated by the Conwy Valley. -

Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire THE CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire R J Silvester, C H R Martin and S E Watson March 2014 Report for Cadw The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 www.cpat.org.uk © CPAT 2014 CPAT Report no. 1257 Historic Settlements in Denbighshire, 2014 An introduction............................................................................................................................ 2 A brief overview of Denbighshire’s historic settlements ............................................................ 6 Bettws Gwerfil Goch................................................................................................................... 8 Bodfari....................................................................................................................................... 11 Bryneglwys................................................................................................................................ 14 Carrog (Llansantffraid Glyn Dyfrdwy) .................................................................................... 16 Clocaenog.................................................................................................................................. 19 Corwen ...................................................................................................................................... 22 Cwm ......................................................................................................................................... -

Clwyd Catchment Summary 2016

Clwyd Management Catchment Summary Date Contents 1. Background to the Clwyd Management Catchment summary ......................................... 3 2. The Clwyd Management Catchment ................................................................................ 4 3. Current Status of the water environment ......................................................................... 7 4. The main challenges ........................................................................................................ 9 5. Objectives and measures .............................................................................................. 11 6. Water Watch Wales ....................................................................................................... 18 Page 2 of 19 www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk 1. Background to the Clwyd Management Catchment summary This management catchment summary supports the 2015 updated Western Wales River Basin Management Plan (RBMP). Along with detailed information on the Water Watch Wales (WWW) website, this summary will help to inform and support delivery of local environmental improvements to our groundwater, rivers, lakes, estuaries and coasts. Information on WWW can be found in Section 6. Natural Resources Wales has adopted the ecosystem approach from catchment to coast. This means being more joined up in how we manage the environment and its natural resources to deliver economic, social and environmental benefits for a healthier, more resilient Wales. It means considering the environment as a whole, -

Bryn Asaph & Bryn Asaph Bach ST ASAPH, DENBIGHSHIRE

Bryn Asaph & Bryn Asaph Bach ST ASAPH, DENBIGHSHIRE www.jackson-stops.co.uk Accommodation in Brief An imposing John Lot 1 - Bryn Asaph Douglas manor house with • Vestibule, Lobby, Staircase Hall, Drawing Room, Dining Room, Sitting Room, Study, Office/Games Room, Kitchen with Dining Area, Cellar, Boot Room • Master Bedroom with Dressing Room and Bathroom, 7 further Bedrooms, 4 Bath/Shower Rooms adjoining cottage situated (4 En-Suite), Laundry Room/Bedroom 5, Study Area, Tower Storage • Formal Gardens, Orchard, Woodland, Pasture, River Frontage, In all about 10 acres (4.04ha) amongst beautiful gardens Lot 2 - Bryn Asaph Bach • Hall, Kitchen, Dining Room, Sitting Room, Study, Utility, WC with river frontage and • Master Bedroom with En-Suite Bathroom, 3 further Bedrooms, 2 Bath/Shower Rooms (1 en-suite) • Former Wood Store, Patio, Garden, Parking. pasture Further land and properties may be available by separate negotiation. Description Bryn Asaph is fully deserving of its Grade II listing being constructed of brick under a slate roof with a distinctive asymmetrical Arts & Crafts façade with tall chimney stacks, prominent turret, sash windows and recently replaced decorative barge boards and finials. To the rear of the property is an ornate cast iron verandah which takes full advantage of the beautiful gardens and grounds providing a pleasant sitting area. Internally, the property has an abundance of period features throughout in particular the fireplaces, tall ceilings and decorative moldings and it has the benefit of gas central heating which was recently installed in 2010 with two new independent systems for the first floor and the second floor. -

TEULU ASAPH Diocese of St Asaph February/March 2014

FREE TEULU ASAPH Diocese of St Asaph February/March 2014 THE JEWELS IN OUR CROWN Before becoming Bishop of St Asaph, Bishop Gregory schools, and contributes the majority of the cost. I think was a school chaplain. Here he tells us why faith schools that is a wise decision. The Wales Government recognis- are so important for educating our children in Wales. es that education is too important a matter to let one size fit all. Diversity of educational provision allows different Our Church schools were described by one of the Church models of education to be tested out against each other. in Wales Review team as “the jewel in the crown”. We are committed to a model which puts concerns for The Church in Wales is Wales’ largest provider of spiritual education, for values and ethos, in prime education after the State, a position that we’re position, and we have distinctive insights and proud to have held for centuries. There contributions to make. are 168 Church in Wales schools, edu- That’s why I support Ysgol Llanbedr in cating 21,000 children and employ- THE Ruthin, for instance – it is important ing 3000 staff. Almost a third of not to lose faith based provision these are in our Diocese. Just in this part of Denbighshire. 6.4p in the pound of parish JEWELS IN Closing Ysgol Llanbedr share is spent support- would do a huge dis- ing our schools, which service to future gen- makes the work the di- OUR erations of children, re- ocese does incredible value. -

Walks from the Ruthin Castle Hotel

THE RUTHIN CASTLE HOTEL three circular walks from the Castle Street, Ruthin, North Wales LL15 2NU web www.ruthincastle.co.uk email [email protected] tel +44 (0) 1824 702664 The beautiful, wooded valley of the Afon Clywedog is followed by a track known as Lady Bagot’s Drive. The Bagots were local landowners, and Rhyd-y-cilgwyn was part of their estate. Stonechats are common in the Clwydian Hills and have a sharp call that Moel Famau is the highest point of the sounds like two stones Clwydian Hills and lies on the route of being tapped together. the Offa’s Dyke path. The Jubilee Tower on the summit was built to celebrate the golden jubilee of George III, though it was never completed. The Afon Clwyd rises in Clocaenog Forest and runs for 35 miles to the sea at Rhyl. Sand Martins nest in the banks below Ruthin. River Clwyd 1½ miles: Easy A relaxing stroll to a historic bridge, returning Nantclwyd y Dre along the river and beneath the castle walls. in Castle Street dates from 1435. Two Rivers Walk 5¾ miles: Moderate Over the fields to the beautiful wooded valley of the Afon Clywedog, returning via Rhewl and the Afon Clwyd. This arch of Tunnel Moel Famau Bridge spanned the old 10¾ miles: Strenuous mill leat and is thought An all-day expedition to the highest point in the to be medieval. Clwydian Hills, with magnificent views in all directions. ground and then houses on your right. Bear slightly left to a gate, to foot of a steep rocky slope you come to a meeting of five paths (with River Clwyd the left of some red-brick houses facing you, and follow a narrow and Moel Famau a gate in the wall to the right). -

(Faerdre) Farm St.George, Abergele, LL22 9RT

Gwynt y Mor Outreach Project Fardre (Faerdre) Farm St.George, Abergele, LL22 9RT Researched and written by Gill. Jones & Ann Morgan 2017 Written in the language chosen by the volunteers and researchers & including information so far discovered. PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES © Discovering Old Welsh Houses Contents page 1. Building Description 2 2. Early Background History 7 3. The late15th Century and the 16 th Century 15 4. 17 th Century 19 5. 18 th Century 25 6. 19 th Century 28 7. 20 th Century 35 8. 21 st Century 38 Appendices 1. The Royal House of Cunedda 39 2. The Holland Family of Y Faerdre 40 3. Piers Holland - Will 1593 42 4. The Carter Family of Kinmel 43 5. Hugh Jones - Inventory 1731 44 6. Henry Jones - Will 1830 46 7. The Dinorben Family of Kinmel 47 cover photograph: www.coflein.gov.uk - ref.C462044 AA54/2414 - View from the NE 1 Building Description Faerdre Farm 1 NPRN: 27152 Grade II* Grid reference: SH96277546 The present house is a particularly fine quality Elizabethan storeyed example and bears close similarities with Plas Newydd in neighbouring Cefn Meiriadog, dated 1583. The original approach to the property was by way of an avenue of old sycamores and a handsome gateway. 2 Floor plan 3 Interior The internal plan-form survives largely unaltered and consists of a cross-passage, chimney-backing- on-entry plan with central hall and unheated former parlour to the L of the cross-passage (originally divided into 2 rooms).