The Interface of Hope and History and the Conundrum of Post-War International Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outreach Response DRC Rapid Needs Assessment

RAPID NEEDS ASSESMENT REPORT Out-of-site locations in Una Sana, Tuzla and Sarajevo Canton Bosnia and Herzegovina September, 2020 | 1 This assessment has been carried out in order to update the Danish Refugee Council’s mapping of needs of migrants and asylum seekers’ (people of concern) staying outside of formal reception capacities in Una Sana Canton, Tuzla Canton and Sarajevo Canton, with a focus on access to food, WASH and protection issues. Besides the assessment, available secondary sources were also consulted for capturing as accurate a picture as possible. This assessment report has been supported by the European Commission Directorate General for Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid (DG ECHO). This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. 30-September-2020 | 2 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 -

Water Supply Study for Partner Municipalities

1 INVESTOR: MDG-F DEMOCRATIC ECONOMIC WATERSUPPLY GOVERNANCE P ROJEKAT: STUDIJA U OBLASTI VODOSNABDIJEVANJA ZA PARTNERSKE OPŠTINE P ROJECT: WATER SUPPLY STUDY FOR PARTNER MUNICIPALITIES STUDY FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM BOSANSKI PETROVAC 2011 WATER SUPPLY STUDY FOR BOSANSKI PETROVAC MUNICIPALITY Engineering, Design and Consulting Company Bijeljina INVESTOR: UNDP BIH / MDG-F DEMOCRATIC ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE STUDY FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM BOSANSKI PETROVAC Projektni tim Odgovornost u projektu Slobodan Tadić Program manager UNDP/MDG-F DEG UNDP BiH Haris Fejzibegović Technical Coordinator UNDP/MDG-F DEG Amel Jakupović Financial Coordinator UNDP/MDG-F DEG Zdravko Stevanović Team Leader Voding 92 doo Vladimir Potparević Technical expert Alen Robović Financial expert Ermin Hajder Bosanski Petrovac Municipality Općina Bosanski Petrovac Merima Kahrić Bosanski Petrovac Municipality Senada Mehdin Bosanski Petrovac Municipality Duško Bosnić “ViK” Bosanski Petrovac Vodovod i Kanalizacija Huse Jukić “ViK” Bosanski Petrovac Nadzorni odbor Bosanski Petrovac Jasmin Hamzić “ViK” Bosanski Petrovac Nebojša Budović Technical expert Andreas Stoisits Technical expert Mirjana Blagovčanin Financial expert Željko Ivanović Financial expert Voding 92 doo Branislav Erić Technical expert Milutin Petrović GIS expert Muzafer Alihodžić GIS expert Bobana Pejčić Translator Željka Ivanović Translator Project Manager: Managing Director: Zdravko Stevanović, civ.eng. Vladimir Potparević, civ.eng. Chapter: Registration 2 WATER SUPPLY STUDY FOR BOSANSKI PETROVAC MUNICIPALITY STUDY -

Croatia Atlas

FICSS in DOS Croatia Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected] ((( ((( Kiskunfél(((egyháza ((( Harta ((( ((( ((( Völkermarkt ((( Murska Sobota ((( Szentes ((( ((( ((( Tamási ((( ((( ((( Villach !! Klagenfurt ((( Pesnica ((( Paks Kiskörös ((( ((( ((( Davograd ((( Marcali ((( !! ((( OrOOrorr ss!! MariborMaribor ((( Szank OOrrr ((( ((( ((( Kalocsa((( Kecel ((( Mindszent ((( Mursko Sredisce ((( Kiskunmajsa ((( ((( ((( ((( NagykanizsaNagykanizsa ((( ((( Jesenice ProsenjakovciProsenjakovci( (( CentreCentre NagykanizsaNagykanizsa ((( ((( ((( ProsenjakovciProsenjakovci( (( CentreCentre ((( KiskunhalasKiskunhalas((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( KiskunhalasKiskunhalas Hódmezövásár((( h ((( ((( Tolmezzo ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Sostanj Cakovec ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Dombóvár ((( ((( ((( ((( Kaposvár ((( Forraaskut((( VinicaVinica ((( Szekszárd VinicaVinica (( ((( ((( ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( ((( ((( Jánoshalma ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA Legrad ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA Ruzsa ((( SLOVENIASLOVENIA ((( ((( Csurgó !! ((( ((( !! ((( ((( ((( ((( CeljeCeljeCelje ((( ((( Nagyatád HUNGARYHUNGARY ss ((( ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( CeljeCelje HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARY HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( ss ((( HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( Kamnik ss CeljeCelje HUNGARYHUNGARY ((( Ivanec VarazdinVarazdin ((( ((( VarazdinVarazdin ((( Szoreg Makó ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( -

Northwestern Bosnia

February 1996 Vol. 8, No. 1 (D) NORTHWESTERN BOSNIA Human Rights Abuses during a Cease-Fire and Peace Negotiations SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................2 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................................................................4 BACKGROUND...............................................................................................................................6 ABUSES IN THE SANSKI MOST AREA.......................................................................................7 Summary Executions...........................................................................................................7 AEthnic Cleansing@ of Villages and Towns in the Sanski Most Area...................................9 Stari Majdan .........................................................................................................9 Sanski Most ........................................................................................................13 Kijevo .................................................................................................................15 Poljak..................................................................................................................16 Podbreñje ............................................................................................................17 ehovci ...............................................................................................................18 -

Population Movement

Operation Update Report Bosnia and Herzegovina: Population Movement Emergency appeal n° MDRBA011 GLIDE n° OT-2018-000078-BIH Operation update n° 8 Timeframe covered by this update: Date of issue: 30 July 2021 1 March – 30 June 2021 Operation timeframe: 36 months Operation start date: 8 December 2018 Operation end date: 31 December 2021 Funding requirements: CHF 3,800,000 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 300,000 Appeal coverage: 63 % as of 30 June 2021 (for Donor Response report please click here) N° of people being assisted: 50,000 migrants and 4,500 people (1,500) households from host community Host National Society: Red Cross Society of Bosnia and Herzegovina (RCSBiH) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: ICRC, American Red Cross, Austrian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Bulgarian Red Cross, The Canadian Red Cross Society, China Red Cross – Hong Kong branch, Croatian Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Iraqi Red Crescent, Irish Red Cross, Italian Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, Kuwait Red Crescent Society, New Zealand Red Cross, The Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Red Cross of Monaco, Slovenian Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, Turkish Red Crescent Society, Red Crescent Society of the United Arab Emirates, , Qatar Red Crescent Society Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees, Ministry of Security, Una-Sana Cantonal Government, City of Bihac, IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, Caritas, World Vision, MSF, Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Pomozi.ba, Catholic Relief Services, Save the Children, Austrian Embassy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, International Rescue Committee, International Orthodox Christian Charities Governments supporting the operation: Italian Government, Government of Canada (via Canadian RC), Netherlands Government (via Netherlands RC), Slovenian Government, Swedish Government (via Swedish RC). -

Operation Update Report Bosnia and Herzegovina: Population Movement

Operation Update Report Bosnia and Herzegovina: Population Movement Emergency appeal n° MDRBA011 GLIDE n° OT-2018-000078-BIH Operation update n° 7 Timeframe covered by this update: Date of issue: 1 April 2021 1 September 2020 – 28 February 2021 Operation timeframe: 24 months Operation start date: 8 December 2018 Operation end date: 31 December 2021 (extended from 8 December 2021) Funding requirements: CHF 3,800,000 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 300,000 Appeal coverage: 63% as of 25 March 2021 (for Donor Response report please click here) N° of people being assisted: 50,000 migrants and 4,500 people (1,500 households) from host community Host National Society: Red Cross Society of Bosnia and Herzegovina (RCSBiH) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: American Red Cross, Austrian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Bulgarian Red Cross, Canadian Red Cross, China Red Cross – Hong Kong branch, Croatian Red Cross, German Red Cross, Iraqi Red Crescent, Irish Red Cross, Italian Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Kuwait Red Crescent Society, New Zealand Red Cross, The Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Red Cross of Monaco, Swedish Red Cross, Swiss Red Cross, Turkish Red Crescent Society, Red Crescent Society of the United Arab Emirates, ICRC. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry for Human Rights and Refugees, Ministry of Security, Una-Sana Cantonal Government, City of Bihac, IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, Caritas, World Vision, MSF, Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Pomozi.ba, Catholic Relief Services, Save the Children, Austrian Embassy in Bosnia and Herzegovina, International Rescue Committee, International Orthodox Christian Charities Governments supporting the operation: Italian Government, Government of Canada (via Canadian RC), Netherlands Government (via Netherlands RC), Slovenian Government, Swedish Government (via Swedish RC). -

Poziv Za Prijedloge Projekata Neformalnih Grupa Mladih U Općini Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje

Podržali: POZIV ZA PRIJEDLOGE PROJEKATA NEFORMALNIH GRUPA MLADIH U OPĆINI GORNJI VAKUF-USKOPLJE Omladinska banka je program čiji je cilj povećati učešće mladih u procesima lokalnog razvoja ruralnih sredina kroz dodjelu bespovratnih novčanih sredstava projektima koje pokreću i vode neformalne grupe mladih. Fondacija Mozaik u saradnji sa 31 općinom u BiH podržava rad Omladinskih banaka Bosanska Krupa, Bosanski Petrovac, Bugojno, Brod, Cazin, Goražde, Kladanj, Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje, Lopare, Odžak, Pelagićevo, Petrovo, Prozor-Rama, Živinice, Modriča, Mrkonjić Grad, Šekovići, Tešanj, Usora, Vukosavlje, Zvornik, Doboj Jug, Konjic, Kotor Varoš, Kozarska Dubica, Novi Grad, Novi Travnik, Srbac, Šipovo, Zavidovići i Žepče. Omladinskom bankom Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje uz podršku Fondacije Mozaik i Općine Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje upravlja deset članova odbora, mladi od 15 do 30 godina koji su izabrani na javnom pozivu i edukovani da vode program malih grantova i koji imaju ulogu na osnovu prioriteta i potreba mladih, da raspisuju konkurse i odlučuju o finansiranju projekata neformalnih grupa mladih u opštini/općini Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje. Fond Omladinske banke za projekte neformalnih grupa mladih u općini Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje Fond za projekte mladih u 2014. godini iznosi 13.000 KM koji zajednički obezbjeđuju Fondacija Mozaik od USAID-a i Općina Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje. Omladinska banka Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje ima otvoren poziv za prijedloge projekata od 5.3. do 15.4.2014.godine. Ko može podnijeti prijedlog projekta Omladinskoj banci Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje? • Neformalne grupe mladih od 15 do 30 godina (minimum pet mladih osoba mora biti aktivno uključeno u pripremu i realizaciju projekta) koji žive na području općine Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje; • Oni koji imaju ideje i sposobni su da poboljšaju uslove života mladih u sredini u kojoj žive; • Mladi koji su aktivni i imaju volju, prijatelje, komšije i druge koji su spremni da zavrnu rukave i urade nešto za sebe i svoju zajednicu. -

Interactions of the Effects of Provenances and Habitats on the Growth of Scots Pine in Two Provenance Testsissn in Bosnia 1847-6481 and Herzegovina Eissn 1849-0891

Interactions of the Effects of Provenances and Habitats on the Growth of Scots Pine in Two Provenance TestsISSN in Bosnia 1847-6481 and Herzegovina eISSN 1849-0891 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER DOI: https://doi.org/10.15177/seefor.21-03 Interactions of the Effects of Provenances and Habitats on the Growth of Scots Pine in Two Provenance Tests in Bosnia and Herzegovina Mirzeta Memišević Hodžić1,*, Dalibor Ballian1,2 (1) University of Sarajevo, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Silviculture and Urban Citation: Memišević Hodžić M, Ballian Greenery, Zagrebačka 20, BA-71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; (2) Slovenian D, 2021. Interactions of the Effects Forestry Institute, Večna pot 2, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia of Provenances and Habitats on the Growth of Scots Pine in Two Provenance * Correspondence: e-mail: [email protected] Tests in Bosnia and Herzegovina. South- east Eur for 12(1): 13-20. https://doi. org/10.15177/seefor.21-03. Received: 11 Jan 2021; Revised: 9 Mar 2021; Accepted: 12 Mar 2021; Published online: 11 Apr 2021 ABSTRACT This research aims to determine the interaction of the effects of provenance and habitat conditions on provenance tests on the growth of Scots pine on two experimental plots in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Provenance tests are located on plots with different ecological conditions and altitudes: Romanija Glasinac, 1000 m, and Gostović Zavidovići, 480 m. Both tests include 11 provenances and two clonal seed plantations with 10 families in each, and five repetitions. Tree heights and diameters at breast height were measured at the age of 21 years. Interactions were determined using multivariate analysis for measured traits. -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Investment Opportunities

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA KEY FACTS..........................................................................6 GENERAL ECONOMIC INDICATORS....................................................................................7 REAL GDP GROWTH RATE....................................................................................................8 FOREIGN CURRENCY RESERVES.........................................................................................9 ANNUAL INFLATION RATE.................................................................................................10 VOLUME INDEX OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION IN B&H...............................................11 ANNUAL UNEMPLOYMENT RATE.....................................................................................12 EXTERNAL TRADE..............................................................................................................13 MAJOR FOREIGN TRADE PARTNERS...............................................................................14 FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN B&H.........................................................................15 TOP INVESTOR COUNTRIES IN B&H..............................................................................17 WHY INVEST IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..............................................................18 TAXATION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..................................................................19 AGREEMENTS ON AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION...............................................25 -

National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 36 Issue 5 Article 3 10-2016 National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina Ivan Cvitković University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cvitković, Ivan (2016) "National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 36 : Iss. 5 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol36/iss5/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONAL AND CONFESSIONAL IMAGE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA1 Ivan Cvitković Ivan Cvitković is a professor of the sociology of religion at the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He obtained the Master of sociological sciences degree at the University in Zagreb and the PhD at the University in Ljubljana. His field is sociology of religion, sociology of cognition and morals and religions of contemporary world. He has published 33 books, among which are Confession in war (2005); Sociological views on nationality and religion (2005 and 2012); Social teachings in religions (2007); and Encountering Others (2013). e-mail: [email protected] The population census offers great data for discussions on the population, language, national, religious, social, and educational “map of people.” Due to multiple national and confessional identities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such data have always attracted the interest of sociologists, political scientists, demographers, as well as leaders of political parties. -

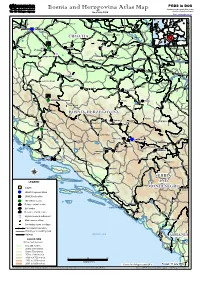

Bosnia and Herzgovina Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section Division of Operational Support As of July 2005 Email : [email protected]

PGDS in DOS Bosnia and Herzgovina Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section Division of Operational Support As of July 2005 Email : [email protected] ))))))))) Mohács ))))))))))))))))) B a j m o k ))))))))))))))))) Bóly ))))))))))))))))) Stanisic ) )))))))) )))))))) R ))) O ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) B j e l o v a r W Zapresic . C ) )))))))) )))))))) S i k l ó s L ))) 3 S a m o b o r ))))))))))))))))) A ) )))))))) )))))))) _ ))) s ) )))))))))))))))) Virovitica ))) a ) )))))))) )))))))) l ) ) ) Backa Topolat ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) ) ) ) Dugo Selo A ))))))))))))))))) ))) ))))))))))))))))) Telecka ZAGREBZAGREBZAGREBZAGREB _ a ) )))))))) )))))))) n ) )) i ))))))))))))))))) ))) S o m b o r Beli Manastir v ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Donji Miholiac o g e z r ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) e ))) Podravska Slatina ))) S i v a c H _ a i ) )))))))) )))))))) n ))))))))))))))))) Apatin ))))))))))))))))) S t a p a r ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) F e k e t i c CROATIA ) )))))))) )))))))) V a l p o v o ))) Crvenka s CROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIACROATIA ) ) ) CROATIA ))) CROATIA o B ))))))))))))))))) ) )))))))))))))))) Kula ))))))))))))))))) ))) Sonta ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Garesnica ))))))))))))))))) V r b a s ! !!!!!!!! Osijek )) CepinCepin ** ))))))))))))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) CepinCepin **Cepin * ))) ))))))))))))))))) Karavukovo KarlovacKarlovacKarlovacKarlovac SisakSisak ))))))))))))))))) KutinaKutinaKutinaKutina SisakSisakSisakSisak ))))))))))))))))) R a t k o v o PetrinjaPetrinja -

Croatia Atlas

PGDS in DOS Croatia Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of July 2005 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ))) ))))))))))))) Kiskunfélegyháza))))))))))))))))) ))))))))))))))))) Harta NN ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Völkermarkt ))) Murska Sobota ))))))))))))))))) S z e n t e s ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Tamási ) )))))))) )))))))) ))))))))))))))))) ))))))))))))))))) ! !!!!!!!! ))) ))) Kiskörös ) )))))))))))))))) Villach Klagenfurt Pesnica Paks ))) ))))))))))))))))) MariborMariborMariborMaribor D a v o g r a d N ) )))))))))))))))) N NNNNNNNNNNNNN ) ) ) N ) ) ) N ))) N < ) )))))))) )))))))) N < <<<<<<<<<<<<< ) ) ) < ) ) ) < Marcali ) )) N < ) ) ) < ) ) ) < < ))) ! !!!!!!!! N ) )))))))) )))))))) Orosháza ! ! N NNNNNNNNNNNNN) )) ! ! N ) ) ) Orosháza s sssssssssssss! ! N N))) Szank OrosházaOrosházaOrosházaOrosháza ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))))))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Kalocsa))) ))) ))) Mursko Sredisce K e c e l ProsenjakovciProsenjakovciProsenjakovciProsenjakovci NagykanizsaNagykanizsaNagykanizsaNagykanizsa ))))))))))))))))) Kiskunmajsa ! !!!!!!!! !!!!!!!! ))))))))))))))))) ! ! ! ) )))))))) )))))))) ! ! ! ) ) ) ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Jesenice ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) ))) ) )))))))) )))))))) 2 ) )))))))) )))))))) ))) Kiskunhalas ) ) ) 2 2222222222222 ) ) ) ))) 2 ) ) ) Tolna 2 ) )) ) )))))))) )))))))) KiskunhalasKiskunhalas 2 ) ) ) ) ) ) 2 ) ) ) ) ) ) 2 ))) ) )))))))) )))))))) ) ) ) ) )))))))) )))))))) KiskunhalasKiskunhalasKiskunhalasKiskunhalas