US International Broadcasting Struggles to Find Its Way—With the Help of Al Jazeera.Ó Transnational Broadcasting Studies 15, Fall 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

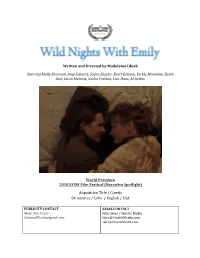

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 Looking Forward to High School and College Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools Elaine M. Allensworth, Julia A. Gwynne, Paul Moore, and Marisa de la Torre TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary Chapter 5 55 Who Is at Risk of Earning Less 7 Introduction Than As or Bs in High School? Chapter 1 Chapter 6 17 Issues in Developing and Indicators of Whether Students Evaluating Indicators 63 Will Meet Test Benchmarks Chapter 2 Chapter 7 23 Changes in Academic Performance Who Is at Risk of Not Reaching from Eighth to Ninth Grade 75 the PLAN and ACT Benchmarks? Chapter 3 Chapter 8 29 Middle Grade Indicators of How Grades, Attendance, and High School Course Performance 81 Test Scores Change Chapter 4 Chapter 9 47 Who Is at Risk of Being Off-Track Interpretive Summary at the End of Ninth Grade? 93 99 References 104 Appendices A-E ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work. We thank Robert Balfanz and Julian Betts for providing us with very thoughtful review and feedback which were used to revise this report. We also thank Mary Ann Pitcher and Sarah Duncan, at the Network for College Success, and members of our Steering Committee, especially Karen Lewis, for their valuable feedback. Our colleagues at UChicago CCSR and UChicago UEI, including Shayne Evans, David Johnson, Thomas Kelley-Kemple, and Jenny Nagaoka, were instrumental in helping us think about the ways in which this research would be most useful to practitioners and policy makers. -

GALE Phase 2 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction

GALE Phase 2 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction GALE Phase 2 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 contains approximately 165 hours of Arabic broadcast news speech collected in 2006 and 2007 by the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC), MediaNet, Tunis, Tunisia and MTC, Rabat, Morocco during Phase 2 of the DARPA GALE program. Broadcast audio for the DARPA GALE (Global Autonomous Language Exploitation) program was collected at LDC’s Philadelphia, PA USA facilities and at three remote collection sites: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology ( HKUST), Hong Kong (Chinese); Medianet (Arabic); and MTC (Arabic). The combined local and outsourced broadcast collection supported GALE at a rate of approximately 300 hours per week of programming from more than 50 broadcast sources for a total of over 30,000 hours of collected broadcast audio over the life of the program. The broadcast conversation recordings in this release feature news broadcasts focusing principally on current events from the following sources: Abu Dhabi TV, a televisions station based in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Al Alam News Channel, based in Iran; Alhurra, a U.S. government-funded regional broadcaster; Aljazeera , a regional broadcaster located in Doha, Qatar; Dubai TV, a broadcast station in the United Arab Emirates; Al Iraqiyah, an Iraqi television station; Kuwait TV, a national broadcast station in Kuwait; Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation, a Lebanese television station; Nile TV, a broadcast programmer based in Egypt, Saudi TV, a national television station based in Saudi Arabia; and Syria TV, the national television station in Syria. 2. Broadcast Audio Data Collection Procedure LDC’s local broadcast collection system is highly automated, easily extensible and robust and capable of collecting, processing and evaluating hundreds of hours of content from several dozen sources per day. -

“The Voice of the Voiceless” News Production and Journalistic Practice at Al Jazeera English

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Social Anthropology “The Voice of the Voiceless” News production and journalistic practice at Al Jazeera English Emma Nyrén i Master’s thesis Spring 2014 Supervisor: Paula Uimonen Abstract This thesis explores how the cultural and social media environments surrounding the journalism of Al Jazeera English are shaped by and shape the channel’s news practices. Al Jazeera English has been described as a contra-flow news organization in the global media landscape and this thesis discusses the different reasons why the channel is described in this way by looking at its origins, aims, characteristics and ideals. Based on interviews with Al Jazeera English journalists, news observations and two field observations in London, I argue that Al Jazeera English brings cultural and social sensitivity to its news reports by engaging with multiple in-depth perspectives, using local reporters and integrating citizen generated material. The channel’s early adoption of online technologies and citizen journalism also contributes to a more democratic news direction and gives the channel a wider spectrum of opinions and perspectives to choose between. By applying a comparative analysis built on similar studies within anthropology of news journalism differences and similarities within the journalistic practices can be detected, comparing Al Jazeera English’s journalism with journalism at other places and news organizations. These comparisons and discussions enables new understandings for how news is produced and negotiated within the global media landscape, and this gives the global citizen an improved comprehension of why the news, which shapes our appreciation of the world, looks like it does. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development's Next Wave Intro

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development’s Next Wave Intro In spring of 2015, LISC NYC’s Executive Director, Sam Marks invited friends of LISC - top economists, policy analysts, journalists, community development gurus and current leaders of some of the city’s top community development corporations - to join staff in strategizing around critical questions facing New York’s community development sector. What can LISC NYC and its community development partners do to counter global and national trends exacerbating economic polarization? What is community development’s role in shaping the city’s upcoming neighborhood rezonings, preserving affordable housing, and, building human capital? How can the industry scale up even as it consolidates and redeploys resources to new areas and programming? Over the course of three panel discussions moderated by Marks, presenters and LISC NYC staff shed some light on next wave strategies for New York City’s neighborhoods. Panel 1: Global City/Global Trends: Panelists explained the global trends driving high real estate prices, economic polarization, gentrification and displacement and debated about the levers available to city government, LISC NYC and community developers to alleviate the harsh impacts on low and moderate income New Yorkers. Jonathan Bowles, Executive Director, Center for an Urban Future . Adam Davidson, co-founder and co-host, Planet Money . Ingrid Gould Ellen, Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Director of the Urban Planning Program, New York University Wagner; Faculty Director, Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy . Chris Herbert, Managing Director, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies Panel 2: Community development past, present and future: Former LISC NYC directors distilled their experiences using real estate strategies to address neighborhood issues and considered strategies to meet current challenges. -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

Community Rebranding: a Case Study

COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Hospitality Management By Michelle L. Pecheck Spring 2015 SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY AUTHOR: Michelle L. Pecheck DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2015 The Collins College of Hospitality Management Dr. Ed Merritt _________________________________________ Project Committee Chair Associate Professor Dr. Margie Jones _________________________________________ Associate Professor Dr. Neha Singh _________________________________________ Director of Graduate Studies Associate Professor ii ABSTRACT Intro: This case study profiles Claremont, a city of approximately 37,000 residents. Since its formation in 1887, it has primarily been known as a college town with a history of citrus production. This case study investigates what components would need to be in place to rebrand or reposition the city as a unique, healthful destination. Case: A resident survey, interviews, and focus groups were used to gather qualitative data about residents’ perceptions of the city’s current brand and potential rebranding. Management & Outcome: Scope of work for the focus city included data gathering from residents, and identification of projects, services, and designations to support marketing of the city as a health/wellness destination. Discussion: Data from surveys, focus groups, and key informant interviews indicated that residents were uncertain of the City’s current brand, in general appeared to care little about the brand, and lacked information about the City’s interest in a possible future rebranding. Further, City documents revealed a history of departmental rebrandings that may have obscured the City’s current brand image. -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Dinner” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 6, folder “3/25/76 - Radio and Television Correspondents' Dinner” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON March 19, 1976 MEMORANDUM TO: RED CAVANEY P~ER SORUM FROM: S AN PORTER . SUBJECT: Mrs; Ford Attendance at the Radio and TV Correspondent's Dinner (Fay Wells), Washington Hilton Hotel, March 26th Mrs. Ford will attend the Radio and TV Correspondent's Dinner as a guest of Fay Wells of Storer Broadcasting Company. Mrs. Ford has attended this dinner as Fay's guest for many years and has been very fond of Fay through the years . She will travel to the dinner with the President (the cocktail period is 6:30-8:00 in the Georgetown Suite). Mrs. Ford then will break from the President and will join Fay and her guests in the Jefferson Room for dinner (I understand the President will be eating in the Ballroom) . -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Comine, Julie Anne, "Shuttlegirl" (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14435. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shuttlegirl by Julie Anne Comine A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Neal Bowers Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1998 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Julie Anne Comine has met the thesis requirements ofIowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy lU for Jeff, with great impatience IV TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Astronaut's Bride 1 The married planet 2 Reputation 3 hoopskirt 4 The Godmother, part 3 1/2 7 To the memory of Mrs. Seuss 8 Canticle of tentacles 9 The torch singer who came in from the cold 10 Sarcastics anonymous 11 dada 12 Decree 13 Breaking down is hard to do 16 The book of Sarah 17 Hymns & hers 19 Diadem 20 II.