Under the Glass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh

The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh 20 BE MY BABY, The Ronettes Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 116 1963 Billboard: #2 DA DOO RON RON, The Crystals Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 112 1963 Billboard: #3 CHRISTMAS (BABY PLEASE COME HOME), Darlene Love Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 119 1963 Did not make pop charts To hear folks talk, Phil Spector made music out of a solitary vision. But the evidence of his greatest hits insists that he was heavily dependent on a variety of assistance. Which makes sense: Record making is fundamentally collaborative. Spector associates like engineer Larry Levine, arranger Jack Nitzsche, and husband-wife songwriters Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich were simply indispensable to his teen-art concoctions. Besides them, every Spector track featured a dozen or more musicians. The constant standouts were' drummer Hal Blaine, one of the most inventive and prolific in rock history, and saxophonist Steve Douglas. Finally, there were vast differences among Spector's complement of singers. An important part of Spector's genius stemmed from his ability to recruit, organize, and provide leadership within such a musical community. Darlene Love (who also recorded for Spector with the Crystals and Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans) ranks just beneath Aretha Franklin among female rock singers, and "Christmas" is her greatest record, though it was never a hit. (The track probably achieved its greatest notice in the mid-eighties, when it was used over the opening credits of Joe Dante's film, Gremlins.) Spector's Wall of Sound, with its continuously thundering horns and strings, never seemed more massive than it does here. -

Directory Download Our App for the Most Up-To-Date Directory Info

DIRECTORY DOWNLOAD OUR APP FOR THE MOST UP-TO-DATE DIRECTORY INFO. E = East Broadway N = North Garden C = Central Parkway S = South Avenue W = West Market m = Men’s w = Women’s c = Children’s NICKELODEON UNIVERSE = Theme Park The first number in the address indicates the floor level. ACCESSORIES Almost Famous Body Piercing E350 854-8000 Chapel of Love E318 854-4656 Claire’s E179 854-5504 Claire’s N394 851-0050 Claire’s E292 858-9903 GwiYoMi HAIR Level 3, North 544-0799 Icing E247 854-8851 Soho Fashions Level 1, West 854-5411 Sox Appeal W391 858-9141 APPAREL A|X Armani Exchange m w S141 854-9400 abercrombie c W209 854-2671 Abercrombie & Fitch m w N200 851-0911 aerie w E200 854-4178 Aéropostale m w N267 854-9446 A’GACI w E246 854-1649 Alpaca Connection m w c E367 883-0828 Altar’d State w N105 763-489-0037 American Eagle Outfitters m w S120 851-9011 American Eagle Outfitters m w N248 854-4788 Ann Taylor w S218 854-9220 Anthropologie w C128 953-9900 Athleta w S145 854-9387 babyGap c S210 854-1011 Banana Republic m w W100 854-1818 Boot Barn m w c N386 854-1063 BOSS HUGO BOSS m S176 854-4403 Buckle m w c E203 854-4388 Burberry m w S178 854-7000 Calvin Klein Performance w S130 854-1318 Carhartt m w c N144 612-318-6422 Carter’s baby c S254 854-4522 Champs Sports m w c W358 858-9215 Champs Sports m w c E202 854-4980 Chapel Hats m w c N170 854-6707 Charlotte Russe w E141 854-6862 Chico’s w S160 851-0882 Christopher & Banks | c.j. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Top 100 Most Requested Songs of the 1960'S

Top 100 Most Requested Songs of the 1960's RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 2 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 3 Beatles Twist And Shout 4 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 5 James, Etta At Last 6 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 7 Presley, Elvis Can't Help Falling In Love 8 Temptations My Girl 9 Armstrong, Louis What A Wonderful World 10 Righteous Brothers Unchained Melody 11 Four Tops I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) 12 Checker, Chubby The Twist 13 Sinatra, Frank Fly Me To The Moon 14 Beatles All You Need Is Love 15 Franklin, Aretha Respect 16 Cash, Johnny Ring Of Fire 17 Checker, Chubby Let's Twist Again 18 Sledge, Percy When A Man Loves A Woman 19 Orbison, Roy Oh, Pretty Woman 20 Dion Runaround Sue 21 King, Ben E. Stand By Me 22 Temptations Ain't Too Proud To Beg 23 Beatles I Saw Her Standing There 24 Cole, Nat King L-O-V-E 25 Gaye, Marvin & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 26 Archies Sugar, Sugar 27 Beatles In My Life 28 Rolling Stones (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction 29 Contours Do You Love Me 30 Beatles I Want To Hold Your Hand 31 Redding, Otis (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay 32 Valli, Frankie Can't Take My Eyes Off You 33 Brown, James & The Famous Flames I Got You (I Feel Good) 34 Gaye, Marvin How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) 35 Sinatra, Frank I've Got You Under My Skin 36 Pickett, Wilson Mustang Sally 37 Presley, Elvis A Little Less Conversation 38 Beach Boys God Only Knows 39 Beatles Can't Buy Me Love 40 Beach Boys Wouldn't It Be Nice 41 Beatles When -

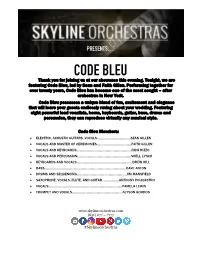

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Pdf, 235.60 KB

00:00:00 Music Transition “Switchblade Comb” by Mobius VanChocStraw. A jaunty, jazzy tune reminiscent of the opening theme of a movie. Music continues at a lower volume as April introduces herself and her guest, and then it fades out. 00:00:08 April Wolfe Host Welcome to Switchblade Sisters, where women get together to slice and dice our favorite action and genre films. I’m April Wolfe. Every week, I invite a new female filmmaker on. A writer, director, actor, or producer, and we talk—in depth—about one of their fave genre films. Perhaps one that’s influenced their own work in some small way. And you may already know, but a reminder that we are remote recording now, and I’m recording from my bedroom. So I’m going to warn you right now that you will hear trash trucks, birds, um, a menagerie of cats. It’s all going to be going on in the background. The audio will be a little bit different than the studio’s, but everything else is going to be the same. The only thing different today, however, is our guest, because I’m very excited to have writer-actor Hannah Bos here. Hannah, how are you today? 00:00:51 Hannah Bos Guest I’m okay. I’m a little tired. Pretty good, but pretty pooped. 00:00:54 April Host Oh, hanging in there. 00:00:55 Hannah Guest I’m on uh—got a toddler, so it’s keeping me very busy. 00:01:01 April Host Yeah, as it turns out, toddlers do toddle. -

Leon Russell – Primary Wave Music

ARTIST:TITLE:ALBUM:LABEL:CREDIT:YEAR:LeonThisCarneyTheW,P1972TightOutCarpentersAA&MWNow1973IfStopP1974LadyWill1975 SongI Were InRightO' Masquerade &AllBlueRussellRope The Thenfor Thata Stuff CarpenterYouWoodsWisp Jazz LEON RUSSELL facebook.com/LeonRussellMusic twitter.com/LeonRussell Imageyoutube.com/channel/UCb3- not found or type unknown mdatSwcnVkRAr3w9VBA leonrussell.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Russell open.spotify.com/artist/6r1Xmz7YUD4z0VRUoGm8XN The ultimate rock & roll session man, Leon Russell’s long and storied career included collaborations with a virtual who’s who of music icons spanning from Jerry Lee Lewis to Phil Spector to the Rolling Stones. A similar eclecticism and scope also surfaced in his solo work, which couched his charmingly gravelly voice in a rustic yet rich swamp pop fusion of country, blues, and gospel. Born Claude Russell Bridges on April 2, 1942, in Lawton, Oklahoma, he began studying classical piano at age three, a decade later adopting the trumpet and forming his first band. At 14, Russell lied about his age to land a gig at a Tulsa nightclub, playing behind Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks before touring in support of Jerry Lee Lewis. Two years later, he settled in Los Angeles, studying guitar under the legendary James Burton and appearing on sessions with Dorsey Burnette and Glen Campbell. As a member of Spector’s renowned studio group, Russell played on many of the finest pop singles of the ’60s, also arranging classics like Ike & Tina Turner’s monumental “River Deep, Mountain High”; other hits bearing his input include the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man,” Gary Lewis & the Playboys’ “This Diamond Ring,” and Herb Alpert’s “A Taste of Honey.” In 1967, Russell built his own recording studio, teaming with guitarist Marc Benno to record the acclaimed Look Inside the Asylum Choir LP. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

The Wrecking Crew—Whether You Knew It Or Not

HISTORY JUNE 2012 Kent Hartman “You are in for a big surprise!” —Dusty street The Inside StoryWrecking of Rock and Roll’s Best-Kept Crew Secret Part Hit Men and part Laurel Canyon, this hidden history of rock and roll chronicles the uncredited studio musi- cians who provided the soundtrack for a generation dur- ing the 1960s and 1970s. If you were a fan of popular music in the 1960s and early ’70s, you were a fan of the Wrecking Crew—whether you knew it or not. On hit record after hit record by everyone from the Byrds, the Beach Boys, and the Monkees to the Grass Roots, the 5th Dimension, Sonny & Cher, and Simon & Garfunkel, this collection of West Coast studio musicians from diverse backgrounds established themselves as the driving sound of pop music—sometimes over the objection of actual band members forced to make way for Wrecking Crew members. Industry insider Kent Hartman tells the dramatic, definitive story of the musicians who forged a reputation throughout the business as the secret weapons behind the top recording stars. Mining invaluable interviews, the author follows the Read by Dan John Miller careers of such session masters as drummer Hal Blaine Category: History/Music and keyboardist Larry Knechtel, as well as trailblazing Running Time: 10 hrs 30 min - Unabridged bassist Carol Kaye. Listeners will discover the Wrecking Hardcover: 02/14/2012 (35,000 Thomas Dunne Books) Territory: US and Canada Crew members who would forge careers in their own right, On Sale Date: 06/18/2012 including Glen Campbell and Leon Russell, and learn of Trade 9781452608068 9 Audio CDs $39.99 the relationship between the Crew and such legends as Phil Library 9781452638065 9 Audio CDs $83.99 Spector and Jimmy Webb. -

LSUG July 29Th 2012

Next Sunday Special Guest Monkee Micky Dolenz! PLAYLIST JULY 29th, 2012 HOUR 1 George Harrison – Bangla Desh George wrote the song in “ten minutes,” for his friend, Ravi Shankar’s war-torn homeland. While in LA working on the soundtrack for the Raga film, Ravi informed George of the atrocities occurring in his native India. Leon Russell, who played keyboards on the session, contributed the idea for the “story” introduction to the song. The song included George, Eric Clapton, Ringo, Bobby Keys, Billy Preston and Leon Russell. Although the lineup is disputed by Jim Horn, who recalls that himself, George, Leon Russell, Klaus Voorman and Jim Keltner were present. voice break The Beatles - I Should Have Known Better - A Hard Day’s Night (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John Following their triumphant visit to America The Beatles were thrust back to work. On February 25, 1964 they dove into new songs slated for their film. On this day they recorded “You Can’t Do That” and began work on Paul’s “And I Love Her” and John’s “I Should Have Known Better.” In the film “I Should Have Known Better” was performed in the train compartment scene, which in reality was the interior of a van with crew members rocking the van to fake the train in motion. Used as the flip side of the U.S. “A Hard Day’s Night” single. Paul’s “Things We Said Today” was the UK b-side. Recorded Feb. 25-26, 1964. On U.S. album: A Hard Day’s Night - United Artists LP Hey Jude - Apple LP (1970) The Beatles - I’m Happy Just To Dance With You - A Hard Day’s Night (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: George Written by John and Paul specifically to give George a song in the movie “A Hard Day’s Night.” Completed in four takes on March 1, 1964, with filming slated to begin the next day.