Northern Pacific Coast Regional Shorebird Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View the Apr/May Issue of the Sandpiper (Pdf)

The andpiper APRIL/MAY 2018 Redwood Region Audubon Society www.rras.org S APRIL/MAY FIELD TRIPS Every Saturday: Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary. Sunday, April 8: Humboldt Bay National Wildlife carpooling available. Walks generally run 2-3 hours. All These are our famous, rain-or-shine, docent-led fi eld trips at Refuge. This is a wonderful 2-to 3-hour trip for people ages, abilities and interest levels welcome! For more the Marsh. Bring your binocular(s) and have a great morning wanting to learn the birds of the Humboldt Bay area. It information, please contact Melissa Dougherty at 530-859- birding! Meet in the parking lot at the end of South I Street takes a leisurely pace with emphasis on enjoying the birds! 1874 or email [email protected]. (Klopp Lake) in Arcata at 8:30 a.m. Trips end around 11 a.m. Beginners are more than welcome. Meet at the Refuge Walks led by: Cédric Duhalde (Apr 7); Cindy Moyer (Apr Visitor Center at 9 a.m. Call Jude Power (707-822- 3613) Saturday, April 14: Shorebird Workshop, Part 14); Michael Morris (Apr 21); Christine Keil (Apr 28). If you for more information. III at Del Norte Pier. Meet at 10 a.m. to watch the are interested in leading a Marsh walk, please contact Ken rising tide at the foot of W. Del Norte St. bring in waves Burton at [email protected]. Sunday, April 8: Shorebird Workshop, Part II of godwits, willets, turnstones, and curlews. Tide will turn at South Spit. First we’ll look for beach-loving around noon; we hope to see a good show by then. -

Arcata Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary Bird Checklist

Arcata Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary Bird Checklist Arcata, Humboldt County, California (Updated Fall 2014) The following list of 327 species was updated by Rob Fowler and David Fix in 2014 from the list they compiled in 2009. Data came from sightings entered in eBird; Stanley Harris's Northwest California Bird (2005, 1996, 1991); historical records in North American Birds magazine and its supporting unpublished Humboldt County summaries; the 2006 edition Arcata Marsh bird checklist (Elias Elias); the 1995 edition Arcata Marsh bird checklist (Kristina Van Wert); and personal communications with many birders. Formatting by Camden Bruner. Call the Northwest California Bird Alert at (707) 822-5666 to report or hear reports of rare birds! Abbreviations: A - Abundant; occurs in large numbers C - Common; likely to be found U - Uncommon; occurs in small numbers, found with seearching R - Rare; expected in very small numbers, not likely to be found Ca - Casual; several records, possibly may occur regularly Ac - Accidental; 1-3 records, not reasonably expected to occur Sp - Spring (Marsh - May) S - Summer (June to mid-July) F - Fall (mid-July through November) W - Winter (December through February) Here Waterfowl: Breeds Spring Summer Fall Winter _____ Greater White-fronted Goose R R R _____ Emperor Goose Ac _____ Snow Goose Ca Ca Ca _____ Ross's Goose Ca Ca Ca _____ Brant U Ac U R _____ Cackling Goose A U C _____ Canada Goose C C C C yes _____ Tundra Swan Ca Ca _____ Wood Duck U U U U yes _____ Gadwall C C C C yes _____ Eurasian Wigeon R U R _____ -

Birdlife International for the Input of Analyses, Technical Information, Advice, Ideas, Research Papers, Peer Review and Comment

UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Doc.10 Annex 2b CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2: Review of Current Knowledge of Bird Flyways, Principal Knowledge Gaps and Conservation Priorities Compiled by: JEFF KIRBY Just Ecology Brookend House, Old Brookend, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, GL13 9SQ, U.K. June 2010 Acknowledgements I am grateful to colleagues at BirdLife International for the input of analyses, technical information, advice, ideas, research papers, peer review and comment. Thus, I extend my gratitude to my lead contact at the BirdLife Secretariat, Ali Stattersfield, and to Tris Allinson, Jonathan Barnard, Stuart Butchart, John Croxall, Mike Evans, Lincoln Fishpool, Richard Grimmett, Vicky Jones and Ian May. In addition, John Sherwell worked enthusiastically and efficiently to provide many key publications, at short notice, and I’m grateful to him for that. I also thank the authors of, and contributors to, Kirby et al. (2008) which was a major review of the status of migratory bird species and which laid the foundations for this work. Borja Heredia, from CMS, and Taej Mundkur, from Wetlands International, also provided much helpful advice and assistance, and were instrumental in steering the work. I wish to thank Tim Jones as well (the compiler of a parallel review of CMS instruments) for his advice, comment and technical inputs; and also Simon Delany of Wetlands International. Various members of the CMS Flyway Working Group, and other representatives from CMS, BirdLife and Wetlands International networks, responded to requests for advice and comment and for this I wish to thank: Olivier Biber, Joost Brouwer, Nicola Crockford, Carlo C. Custodio, Tim Dodman, Roger Jaensch, Jelena Kralj, Angus Middleton, Narelle Montgomery, Cristina Morales, Paul Kariuki Ndang'ang'a, Paul O’Neill, Herb Raffaele and David Stroud. -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Nesting Birds and Two Fox Species

BIODIVERSITY CHANGES AT THE INTERFACE OF MARINE AND TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS: Nesting birds and two fox species David R. Klein, University of Alaska Fairbanks, AK Heather Renner, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Homer, AK Richard Kleinleder, URS, Homer, AK Climate warming in the Arctic and Subarctic has brought about decline in the seasonal extent of sea ice, rising sea levels, accelerated coastal erosion, and changes in the distribution and biodiversity of species of mammals and birds. What are the consequences of these climate- induced changes for nesting birds and resident mammals at the ecosystem and species levels on the St. Matthew Islands? The St. Matthew Islands, now part of Alaska, were discovered during an exploration cruise by Lieutenant Synd of the Russian Navy in the mid-1760’s. Captain Cook “re-discovered” and named the islands in 1778. •In 1909, St. Matthew and adjacent islands were given protective status as a bird reserve by President Theodore Roosevelt, designated as the Bering Sea Reservation These islands attained “Wilderness” status within the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980 Several million sea birds, including >15 species, nest on the St. Matthew Islands, and walrus, sea lions, and seals haul out there Pinnacle Is. There are two vertebrate species endemic to these islands McKay’s bunting Plectrophenax hyperboreus Singing vole Microtus abreviatus Ian Jones photo The St. Mathew Islands are the nesting location for the major portion of the Bering Sea rock sandpiper population The St. Matthew Islands include 3 islands, the largest is about 52 km long, as the biologist walks, and averages ~6 km wide. -

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Rock Sandpiper, Bering Sea

Alaska Species Ranking System - Rock Sandpiper, Bering Sea Rock Sandpiper, Bering Sea Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Calidris ptilocnemis tschuktschorum Note: This assessment refers to this subspecies only. Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 03 December 2018 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN:Least Concern Audubon AK: S Rank: S4B, S3N USFWS: BLM: Sensitive Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 -24 Action -40 to 40 12 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown (ASG 2019). Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -10 Estimated population size is 50,000 (Morrison et al. 2006). Range Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -8 Breeds on Nunivak and St. Lawrence Islands and along the coasts of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and the Seward Peninsula (Kessel 1989; Johnson et al. 2009; Gibson and Withrow 2015). Winter range is most restricted: in Alaska, overwinters from Prince William Sound (Isleib and Kessel 1973) to southeast Alaska (Howe et al. -

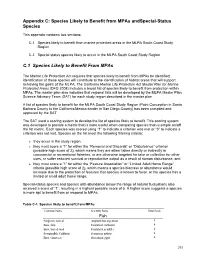

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed Alphabetically by Last Name Of

ABSTRACT BOOK Listed alphabetically by last name of presenting author AOS 2019 Meeting 24-28 June 2019 ORAL PRESENTATIONS Variability in the Use of Acoustic Space Between propensity, renesting intervals, and renest reproductive Two Tropical Forest Bird Communities success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) by fol- lowing 1,922 nests and 1,785 unique breeding adults Patrick J Hart, Kristina L Paxton, Grace Tredinnick from 2014 2016 in North and South Dakota, USA. The apparent renesting rate was 20%. Renesting propen- When acoustic signals sent from individuals overlap sity declined if reproductive attempts failed during the in frequency or time, acoustic interference and signal brood-rearing stage, nests were depredated, reproduc- masking occurs, which may reduce the receiver’s abil- tive failure occurred later in the breeding season, or ity to discriminate information from the signal. Under individuals had previously renested that year. Addi- the acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH), acoustic space is tionally, plovers were less likely to renest on reservoirs a resource that organisms may compete for, and sig- compared to other habitats. Renesting intervals de- naling behavior has evolved to minimize overlap with clined when individuals had not already renested, were heterospecific calling individuals. Because tropical after second-year adults without prior breeding experi- wet forests have such high bird species diversity and ence, and moved short distances between nest attempts. abundance, and thus high potential for competition for Renesting intervals also decreased if the attempt failed acoustic niche space, they are good places to examine later in the season. Lastly, overall reproductive success the way acoustic space is partitioned. -

Rock Sandpiper, Pribilof

Alaska Species Ranking System - Rock Sandpiper, Pribilof Rock Sandpiper, Pribilof Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Calidris ptilocnemis ptilocnemis Note: This assessment refers to this subspecies only. Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 03 December 2018 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5T2T3 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN:Least Concern Audubon AK:Yellow S Rank: S3B,S2N USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: IV. Orange unknown status and high biological vulnerability and action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 4 Action -40 to 40 4 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown (ASG 2019). Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -6 Estimated population size is 19,800 individuals (95% CI = 17,853-21,930; Ruthrauff et al. 2012). Range Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) 8 Breeding is restricted to four Bering Sea islands: St. Paul, St. George, St. Matthew, and Hall (Ruthrauff et al. 2012). Estimated breeding range is <530 sq. km (Ruthrauff et al. 2012). Wintering range is uncertain, though most of the population is believed to overwinter in upper Cook Inlet (Ruthrauff et al. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

2008. Birds of Conservation Concern 2008

BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN 2008 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Bird Management Arlington, Virginia December 2008 BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN 2008 Prepared by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Bird Management Arlington, Virginia Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Birds of Conservation Concern 2008. United States Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Arlington, Virginia. 85 pp. [Online version available at <http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/>] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................. i LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................3 Why Did We Create Lists at Different Geographic Scales?................................................3 Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs).........................................................................3