How Biased and Realistic Media Portrayals of Mental Illness Affect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

February 2019 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle February 2019 The Next NASFA Meeting is Saturday 16 February 2018 at Willowbrook Madison normal 3rd Saturday, except: d Oyez, Oyez d • 23 March—a week late (4th Saturday) to avoid MidSouthCon All meetings are currently scheduled to be at the church, with The next NASFA Meeting will be 16 February 2019, at the the Business Meeting starting at 6P. However, as programs for regular meeting location and the regular time (6P). See the map the year develop, changes may be made to the place, the start below, at right for directions to Willowbrook Baptist Church time, or both. Stay tuned. (Madison campus; 446 Jeff Road). See the map on page 2 for a SHUTTLE DEADLINES closeup of parking at the church as well as how to find the In general, the monthly Shuttle production schedule (though meeting room (“The Huddle”), which is close to one of the a bit squishy) is to put each issue to bed about 6–8 days before back doors toward the north side of the church. Please do not the corresponding monthly meeting. Submissions are needed as try to come in the (locked) front door. far in advance of that as possible. FEBRUARY PROGRAM Please check the deadline below the Table of Contents each The February Program will be a talk by Glenn Taylor, man- month to submit news, reviews, LoCs, or other material. ager of the Huntsville Regional Traffic Management Center of JOINING THE NASFA EMAIL LIST the Alabama Department of Transportation. The topic is AL- All NASFAns who have email are urged to join our email DOT’s Intelligent Transportation System, the goal of which is list, which you can do online at <tinyurl.com/NASFAEmail>. -

Serie Netflix 13 Reasons Why: Consideraciones Para Educadores

Serie Netflix 13 Reasons Why: Consideraciones para Educadores Las escuelas desempeñan un papel importante en la prevención del suicidio de los jóvenes, y la toma de conciencia de los posibles factores de riesgo en la vida de los estudiantes es vital para esta responsabilidad. La serie de moda de Netflix 13 Reasons Why (13 Razones por qué), basada en una novela de adultos jóvenes del mismo nombre, está planteando tales preocupaciones. La serie gira alrededor de Hannah Baker, de 17 años de edad, quien se quita la vida y deja grabaciones de audio para 13 personas que dice de alguna manera fueron parte de por qué se suicidó. Cada cinta relata acontecimientos dolorosos en los cuales uno o más de los 13 individuos desempeñaron un papel. Los productores del programa dicen que esperan que la serie ayude a los que pueden estar luchando con pensamientos de suicidio. Sin embargo, la serie, que muchos adolescentes están viendo en exceso sin la orientación y el apoyo de adultos, está planteando preocupaciones de expertos en prevención de suicidios sobre los riesgos potenciales que plantea el tratamiento sensacionalista del suicidio juvenil. La serie representa gráficamente una muerte por suicidio y aborda en detalle desgarrador una serie de temas difíciles, tales como la intimidación, la violación, el conducir ebrio y la vergüenza. La serie también destaca las consecuencias de que los adolescentes sean testigos de agresión e intimidación (es decir, espectadores) y no tomen medidas para resolver la situación (por ejemplo, no hablar en contra del incidente, no decirle a un adulto sobre el incidente). -

Mental Health Theming in Bojack Horseman Peyton Barranco COM

Mental Health Theming in BoJack Horseman Peyton Barranco COM 262: Research Methods in Media Studies May 15, 2020 Introduction Netflix’s adult animated comedy series BoJack Horseman follows the titular character, BoJack Horseman (Will Arnett), who is an anthropomorphic horse and a washed-up celebrity. BoJack struggles with depression and substance abuse issues, and he has difficulty maintaining healthy relationships. The animated world of BoJack Horseman is a bright, colorful image of Hollywood which is populated by an array of both anthropomorphic animals and humans. Despite the series’ vivid art style and its quick-witted humor, BoJack Horseman investigates themes related to mental health, such as depression, substance abuse, and trauma. As the show progresses throughout its six seasons, the series dives deeper into these themes. Though these themes on mental health are primarily conveyed through BoJack’s character arc, the supporting cast have their own plotlines which communicate different perspectives on these same themes. It is noteworthy that BoJack Horseman, an adult animated comedy about a depressed anthropomorphic horse, offers an insightful and artistic representation of themes on depression and trauma. BoJack Horseman is relatively unique in its nuanced representation of mental illness. Though the series is an animated adult comedy, there are few other television series or films that approach mental illness with a similar combination of tact and creativity. BoJack Horseman may be able to provide insight into how sophisticated representations of mental illness in media can impact viewers’ attitudes towards or impressions of mental illness. In this research paper, I investigate how BoJack Horseman makes use of its genre and animated medium to communicate its themes related to mental health. -

13 Reasons Why: Plot Summary and Content Warnings

13 Reasons Why: Plot summary and content warnings If you haven’t seen 13 Reasons Why but want to discuss it with a young person, or are trying to decide whether it is suitable viewing for a young person in your care, this summary may help. It covers the basic plot and describes content that viewers may find disturbing. 13 Reasons Why is not consistent with many guidelines for media reporting and depiction of suicide, and watching it may be distressing for young people, especially those who are vulnerable. 13 Reasons Why is a high school based drama recently released internationally on Netflix. All 13 hour-long episodes were released together, on March 31st 2017. It is the story of Hannah, a young woman who has died by suicide before the show starts. She has left a box of audio-tapes with Clay, the protagonist of the show, each revealing one of the 13 reasons why she decided to die. On the tapes, she details a number of highly traumatic events that contributed to her developing thoughts of suicide, mostly involving her classmates. Clay is the last of several people who were to listen to the tapes, according to her instructions. As Clay plays them, he learns about many things that happened during Hannah’s life. Classmates who have already heard the tapes are involved at various points, providing additional (sometimes conflicting) information and trying to Keep him on tracK. On the surface, the show clearly set out to do something important, liKe the novel of the same name; to show that actions have consequences. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

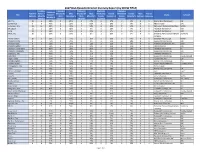

Report by Show Title

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SHOW TITLE) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined TotAl # of FemAle + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by FemAle Directed by FemAle Male FemAle Title FemAle + Studio Network Episodes Minority Male CaucasiAn % Male Minority % FemAle CaucasiAn % FemAle Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes CaucasiAn Minority CaucasiAn Minority 100, The 12 4 33% 8 67% 2 17% 2 17% 0 0% 0 0 Warner Bros Companies CW 12 Monkeys 8 6 75% 2 25% 5 63% 1 13% 0 0% 0 0 NBC Universal Syfy 13 Reasons Why 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 Paramount Pictures Corporation Netflix 24: Legacy 11 2 18% 9 82% 0 0% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX A.P.B. 11 4 36% 7 64% 2 18% 1 9% 1 9% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX Affair, The 10 1 10% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% 0 0 Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Skydance Pictures, LLC Netflix American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC American Gods 9 2 22% 7 78% 1 11% 1 11% 0 0% 0 0 Fremantle Productions, Inc. Starz! American Gothic 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 CBS Companies CBS American Horror Story 10 8 80% 2 20% 2 20% 5 50% 1 10% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC Americans, The 13 6 46% 7 54% 2 15% 3 23% 1 8% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX Andi Mack 13 3 23% 10 77% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 1 Disney/ABC Companies Disney Channel Angie Tribeca 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 1 10% 1 10% 0 0 Turner Films, Inc. -

Animals and Social Critique in Bojack Horseman

Animals and Social Critique in BoJack Horseman Word count: 19,680 Lander De Koster Student number: 01402278 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Marco Caracciolo A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in de Vergelijkende Moderne Letterkunde Academic year: 2017 – 2018 Statement of Permission For Use On Loan The author and the supervisor give permission to make this master’s dissertation available for consultation and for personal use. In the case of any other use, the copyright terms have to be respected, in particular with regard to the obligation to state expressly the source when quoting results from this master’s dissertation. The copyright with regard to the data referred to in this master’s dissertation lies with the supervisor. Copyright is limited to the manner in which the author has approached and recorded the problems of the subject. The author respects the original copyright of the individually quoted studies and any accompanying documentation, such as tables and graphs. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1: Analysis of the Character BoJack Horseman .................................................................... 9 Chapter 2: Theoretical Background: Postmodernity According to Theories by Baudrillard and Simmel ............................................................................................................................................ -

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report Trends in 2016 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Trends in 2016 Executive Summary } This year saw the release of several new, popular digital } The release of popular titles such as The Grand Tour originals. Three first-season titles — Stranger Things, and The Man in the High Castle caused demand Marvel’s Luke Cage, and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the for Amazon Video to grow by over six times in some Life — had the highest peak demand in 2016 in seven markets, such as the UK, Sweden, and Japan, in Q4 of out of the ten markets. All three ranked within the 2016, illustrating the importance of hit titles for SVOD top ten titles by peak demand in nine out of the ten platforms. markets. } Drama series had the most total demand over the } As a percentage of all demand for digital original series year in these markets, indicating both the number and this year, Netflix had the highest share in Brazil and popularity of titles in this genre. third-highest share in Mexico, suggesting that the other platforms have yet to appeal to Latin American } However, some markets had preferences for other markets. genres. Science fiction was especially popular in Brazil, while France, Mexico, and Sweden had strong } Non-Netflix platforms had the highest share in Japan, demand for comedy-dramas. where Hulu and Amazon Video (as well as Netflix) have been available since 2015. Digital Original Series with Highest Peak Demand in 2016 Orange Is Marvels Stranger Things Gilmore Girls Club De Cuervos The New Black Luke Cage United Kingdom France United States Germany Mexico Brazil Sweden Russia Australia Japan 2 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. -

New Zealand 13 Reasons Why Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE About the show 13 Reasons Why is a fictional drama series Reasons Why, and to help guide productive that tackles tough real-life issues experienced conversations around the tough topics that the by teens and young people, including sexual series raises and how these situations can be assault, substance abuse, bullying, suicide, gun addressed if experienced. 13 Reasons Why violence and more. This Netflix series focuses seeks to show the importance of empathy on high school student, Clay Jensen and the for others, even when their struggles aren’t aftermath following his friend Hannah Baker’s obvious, and that everyone matters to many, death by suicide after experiencing a series of even when it doesn’t feel that way. painful events involving school friends, leading to a downward spiral of her mental health and This discussion guide has been developed sense of self. Filmed in a candid and often with assistance from New Zealand agencies explicit manner, the series takes an honest look involved in youth well-being. For direct at the issues faced by young people today. The assistance on specific or urgent personal information below is meant to help viewers matters please see the contact list at the end. understand the various issues addressed in 13 Tips for Watching the Show • Parents / guardians / whanau members you know may behave differently from should consider the film classification those portrayed in the show. rating, your views on the subject matter, and the personality of the people you will watch • If there are scenes that feel uncomfortable the show with. -

The Trendera Files

THE TRENDERA FILES Trendera ALL ABOUT GEN Z Volume 8, Issue 3, Summer 2017 Paramount THE TRENDERA FILES: ALL ABOUT GEN Z CONTENTS GEN Z SOCIETAL SHIFTS 39 40 Media Magic Exposed 42 The Female Gaze INTRO 4 44 Algorithm Activism 46 Going Gradeless GEN Z DEEP DIVE 6 MARKETING TO GEN Z 49 07 Meet Gen Z 50 What’s Working Now 12 Their Identities 51 Campaigns We Love 16 Their Goals and Values 20 Their Social Habits NOW TRENDING 22 Their Media Consumption Trendera54 27 Their Expectations of Brands 55 Lifestyle 60 Wellness DECODING GEN Z 63 Entertainment COMMUNICATION 31 66 Fashion/Retail 69 Tech/Digital 34 Meme Culture 37 Know the Slang Paramount2 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT’S HOT 73 74 Kids 75 Teens 76 Gen Z Icons 78 New & Noteworthy: Gen Z Influencers 82 New & Noteworthy: Actors 84 New & Noteworthy: Actresses 86 Gen Z Digital Download 87 New & Noteworthy: Apps STATISTICS 91 94 Gen Z Stats Trendera 157 Multigenerational Stats Paramount3 THE TRENDERA FILES: ALL ABOUT GEN Z Have we finally reached peak Millennial? Our forecast says yes. While we’ll always hold a special place in our hearts for this entitled and empowered group, it’s time to direct our focus to the rising class of culture creators: Gen Z. This group, currently around 6-21 years old, is claiming their influence on the world sooner than any generation before, wielding their power to effect change, drive new trends, and hand up their ideas to the rest of us. For crying out loud, they can barely drive and are already a force to be reckoned with! Parented by Gen X and Gen Y—two generations who couldn’t be more different—Gen Z is a distinct group with a personality all their own.