Section 4: Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM)

Appendix Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM) The Honourable Chief Justice CHEUNG Kui-nung, Andrew Chief Justice CHEUNG is awarded GBM in recognition of his dedicated and distinguished public service to the Judiciary and the Hong Kong community, as well as his tremendous contribution to upholding the rule of law. With his outstanding ability, leadership and experience in the operation of the judicial system, he has made significant contribution to leading the Judiciary to move with the times, adjudicating cases in accordance with the law, safeguarding the interests of the Hong Kong community, and maintaining efficient operation of courts and tribunals at all levels. He has also made exemplary efforts in commanding public confidence in the judicial system of Hong Kong. The Honourable CHENG Yeuk-wah, Teresa, GBS, SC, JP Ms CHENG is awarded GBM in recognition of her dedicated and distinguished public service to the Government and the Hong Kong community, particularly in her capacity as the Secretary for Justice since 2018. With her outstanding ability and strong commitment to Hong Kong’s legal profession, Ms CHENG has led the Department of Justice in performing its various functions and provided comprehensive legal advice to the Chief Executive and the Government. She has also made significant contribution to upholding the rule of law, ensuring a fair and effective administration of justice and protecting public interest, as well as promoting the development of Hong Kong as a centre of arbitration services worldwide and consolidating Hong Kong's status as an international legal hub for dispute resolution services. The Honourable CHOW Chung-kong, GBS, JP Over the years, Mr CHOW has served the community with a distinguished record of public service. -

Official Record of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 1117 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 30 November 1994 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL LEUNG MAN-KIN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. 1118 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

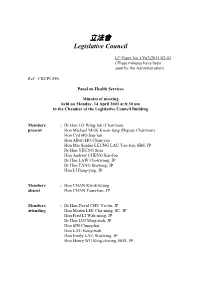

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

The Portrayal of Female Officials in Hong Kong Newspapers

Constructing perfect women: the portrayal of female officials in Hong Kong newspapers Francis L.F. Lee CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG, HONG KONG On 28 February 2000, the Hong Kong government announced its newest round of reshuffling and promotion of top-level officials. The next day, Apple Daily, one of the most popular Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong, headlined their full front-page coverage: ‘Eight Beauties Obtain Power in Newest Top Official Reshuffling: One-third Females in Leadership, Rarely Seen Internationally’.1 On 17 April, the Daily cited a report by regional magazine Asiaweek which claimed that ‘Hong Kong’s number of female top officials [is the] highest in the world’. The article states that: ‘Though Hong Kong does not have policies privileging women, opportunities for women are not worse than those for men.’ Using the prominence of female officials as evidence for gender equality is common in public discourse in Hong Kong. To give another instance, Sophie Leung, Chair of the government’s Commission for Women’s Affairs, said in an interview that women in Hong Kong have space for development, and she was quoted: ‘You see, Hong Kong female officials are so powerful!’ (Ming Pao, 5 February 2001). This article attempts to examine news discourses about female officials in Hong Kong. Undoubtedly, the discourses are complicated and not completely coherent. Just from the examples mentioned, one could see that the media embrace the relatively high ratio of female officials as a sign of social progress. But one may also question the validity of treating the ratio of female officials as representative of the situation of gender (in)equality in the society. -

Democratic Paralysis and Potential in Post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong Copyrighted Material of the Chinese University Press | All Rights Reserved Agnes Tam

Hong Kong Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring 2018), 83–99 In Name Only: Democratic Paralysis and Potential in Post-Umbrella Movement Hong Kong Copyrighted Material of The Chinese University Press | All Rights Reserved Agnes Tam Abstract The guiding principle of the 1997 Handover of Hong Kong was stability. The city’s status quo is guaranteed by Article 5 of the Basic Law, which stipulates the continued operation of economic and political systems for fifty years after the transition from British to Chinese sovereignty. Since the Handover, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) have imposed purposive interpretations on the Basic Law that restrict Hongkongers’ civil participation in local politics. Some official documents of Hong Kong, such as court judgments and public statements, show how the Hong Kong government avails itself to perpetuate such discursive violence through manipulating a linguistic vacuum left by translation issues in legal concepts and their cultural connotations in Chinese and English languages. Twenty years after the Handover, the promise of stability and prosperity in fifty years of unchangedness exists in name only. Highlighting this connection, this article exemplifies the fast-disappearing space for the freedom of expression and for the nominal status quo using the ephemeral appearance of a light installation, Our 60-Second Friendship Begins Now. Embedding the artwork into the skyline of Hong Kong, the artists of this installation adopted the administration’s re-interpretation strategy and articulated their own projection of Hong Kong’s bleak political future through the motif of a count- down device. This article explicates how Hongkongers are compelled to explore alternative spaces to articulate counter-discourses that bring the critical situation of Hong Kong in sight. -

On the Election of the Chief Executive in Hong Kong

- 1 - Viktor Ungemach: On the Election of the Chief Executive in Hong Kong. Head of Government or Lieutenant of Beijing? The election of the Chief Executive held in Hong Kong on March 25, 2007 was the third to take place since the crown colony was returned to the People's Republic of China and transformed into a so-called special administrative region (SAR). Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the former head of government, emerged victorious with 649 of 796 votes, whereas Alan Leong Kah-kit, his challenger from the pro-democratic camp, obtained only 123 votes. Although his programme hardly differed from that of his opponent, Mr Tsang was favoured from the start in the elections, which were accompanied by a public campaign for the first time. Their opinions differed only on the question of introducing universal suffrage, which was strongly advocated by Mr Leong. Properly speaking, the basic law of Hong Kong provides for the election of the Chief Executive to take place in 2007 and that of the Legislative Council in 2008. However, the realisation of these two projects was later predicated on current developments within the SAR, leaving Beijing sufficient scope for influencing Hong Kong politics. When the People's Republic of China said that Hong Kong's population lacked experience in dealing with democracy, it prompted discontent among that population, causing a record number of 500,000 people in the SAR to take to the streets in 2004 and, moreover, initiating the formation of several political parties that demand democracy. However, as their only common denominator was the call for a swift realisation of universal suffrage, the clout of the pro-democratic camp remained weak. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong: China’S Response to Occupy Central and the Future of “One Country, Two Systems”∗

Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong: China’s Response to Occupy Central and the Future of “One Country, Two Systems”∗ Carole J. Petersen† and Alvin Y.H. Cheung†† I.!!!!!!Introduction .............................................................................. 2! II.!!!!The “One Country, Two Systems” Model: Formal Autonomy but with an Executive-Led System ...................... 8! III. Legal Protections for Academic Freedom and Critical Speech in Hong Kong’s Constitutional Framework ............ 13! IV. University Governance: The Impact of Increased Centralization and Control ................................................... 20! V. !Conflicts between The Academic Community and the Hong Kong and Central Governments ................................ 28! VI. Beijing’s Retribution: Increased Interference in Hong Kong Universities ................................................................ 40! VII. The Disapearing Booksellers ............................................... 53! VIII. Conclusion ........................................................................... 58! *Copyright © 2016 Carole J. Petersen and Alvin Y.H. Cheung. The authors thank the academics who agreed to be interviewed for this article and research assistants Jasmine Dave, Jason Jutz, and Jai Keep-Barnes for their assistance with research and editing. This is an updated version of a paper presented at a roundtable organized by the Council on Foreign Relations on December 15, 2015, and the authors thank the chair of the roundtable, Professor Jerome A. Cohen, and other participants for their comments. The William S. Richardson School of Law at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa supported Professor Petersen’s travel to Hong Kong to conduct interviews for this article. † Carole J. Petersen is a Professor at the William S. Richardson School of Law and Director of the Matsunaga Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, University of Hawai’i at Manoa. She taught law at the University of Hong Kong from 1991–2006 and at the City University of Hong Kong from 1989-1991. -

DEFENDING a LANGUAGE: the CANTONESE UMBRELLA MOVEMENT by Joshua S

DEFENDING A LANGUAGE: THE CANTONESE UMBRELLA MOVEMENT by Joshua S. Bacon A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication at Purdue Fort Wayne Fort Wayne, Indiana May 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Wei Luo, Chair Department of Communication Dr. Steven A. Carr Department of Communication Dr. Assem A. Nasr Department of Communication Dr. Lee M. Roberts Department of International Language and Culture Studies Approved by: Dr. Wei Luo 2 Dedicated to the Cantonese people 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...............................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW.................................................................................... 15 Cantonese as a Hong Kong Identity Language ........................................................................ 15 Putonghua as a Colonizing Language ..................................................................................... 18 Cantonese in the Umbrella Movement .................................................................................... 23 Summary ................................................................................................................................ 24 CHAPTER 3. THEORY AND METHODS -

PDF Full Report

Heightening Sense of Crises over Press Freedom in Hong Kong: Advancing “Shrinkage” 20 Years after Returning to China April 2018 YAMADA Ken-ichi NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute Media Research & Studies _____________________________ *This article is based on the same authors’ article Hong Kong no “Hodo no Jiyu” ni Takamaru Kikikan ~Chugoku Henkan kara 20nen de Susumu “Ishuku”~, originally published in the December 2017 issue of “Hoso Kenkyu to Chosa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research]”. Full text in Japanese may be accessed at http://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/oversea/pdf/20171201_7.pdf 1 Introduction Twenty years have passed since Hong Kong was returned to China from British rule. At the time of the 1997 reversion, there were concerns that Hong Kong, which has a laissez-faire market economy, would lose its economic vigor once the territory is put under the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party rule. But the Hong Kong economy has achieved generally steady growth while forming closer ties with the mainland. However, new concerns are rising that the “One Country, Two Systems” principle that guarantees Hong Kong a different social system from that of China is wavering and press freedom, which does not exist in the mainland and has been one of the attractions of Hong Kong, is shrinking. On the rankings of press freedom compiled by the international journalists’ group Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong fell to 73rd place in 2017 from 18th in 2002.1 This article looks at how press freedom has been affected by a series of cases in the Hong Kong media that occurred during these two decades, in line with findings from the author’s weeklong field trip in mid-September 2017.