Joining the Dots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18TOIDC COL 01R2.QXD (Page 1)

OID‰‰†‰KOID‰‰†‰OID‰‰†‰MOID‰‰†‰C New Delhi, Friday,April 18, 2003www.timesofindia.com Capital 28 pages* Invitation Price Rs. 1.50 International India Times Sport Barzan, Saddam’s Alert over Lashkar’s Arsenal hold half-brother caught plan to strike during Manchester United by US Special Forces Vajpayee’s J&K visit to a 2-2 draw Page 12 Page 7 Page 20 WIN WITH THE TIMES Neeraj Paul Established 1838 Bennett, Coleman & Co., Ltd. It’s official: SARS is here You can’t solve a problem on the same level on which it was created. Goan marine Delhi gets another suspect... You have to rise above AP it to the next level. — Albert Einstein engineer NEWS DIGEST Pandya’s ‘murderers’ held: The tests positive CBI has arrested four persons in Andhra Pradesh, who were allegedly By Kalpana Jain & Vidyut Kumar Ta involved in the assassination of for- TIMES NEWS NETWORK mer Gujarat home minister Haren Panaji/New Delhi: When it finally ar- Pandya. P7 rived, it chose the Goan paradise. Train speed 150 kmph now: The confirmation of the first SARS The Indian Railways case in India has come from the idyll of may soon increase sun, sea and sand. Marine engineer its speed limit from Prasheel Wardhe (32), who had sailed to 130 kmph to 150 Hong Kong and Singapore before re- kmph. The promise turning to Mumbai, has tested positive made by railway for the new corona virus, cause of the minister Nitish Ku- pandemic of Severe Acute Respiratory mar came at the VEGGIE Wholesale, Mother Dairy prices Syndrome. -

Tiger Reserves in India 2021 (As on July 2021)

TIGER RESERVES IN INDIA 2021 (AS ON JULY 2021) Updated List of Tiger Reserves in India 2021 (as on July 2021) Dear Champions, preparing for competitive exams must know the Updated list of Tiger Reserves in India which is helps to crack the upcoming exams likes SBI Clerk, RRB PO, RRB Assistants, IBPS PO, IBPS Clerk, SSC exams, TNPSC, etc. Here we give the complete list of Tiger Reserves in India as per July 31, 2021. The Tiger Reserves of India were set up in 1973, which is governed by Project Tiger. The Project Tiger administrated by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NCTA) which was launched in 2005. NCTA is statutory body under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. NCTA is under sec 38 V (1) of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 which is amended Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006. As per July 31, 2021 there are 52 Tiger Reserves in India. Recently Srivilliputhur-Megamalai Tiger Reserve (Tamil Nadu) and Ramgarh Vishdhari Tiger Reserve (Rajasthan) are declared as 51st and 52nd Tiger Reserves of India respectively. List of Tiger Reserves in India 2021 State-wise Andhra Pradesh (1) ✓ Nagarjunsagar Srisailam Tiger Reserve (1982–83) Assam (4) ✓ Manas Tiger Reserve (1973-74) ✓ Nameri Tiger Reserve (1999–2000) ✓ Kaziranga Tiger Reserve (2008–09) ✓ Orang Tiger Reserve (2016) Arunachal Pradesh (3) ✓ Namdapha Tiger Reserve (1982–83) ✓ Pakke or Pakhui Tiger Reserve (1999–2000) ✓ Kamlang Tiger Reserve (2016) Bihar (1) ✓ Valmiki Tiger Reserve (1989–90) Chhattisgarh (3) ✓ Indravati Tiger Reserve (1982–83) ✓ Udanti-Sitanadi Tiger Reserve (2008–09) ✓ Achanakmar Tiger Reserve (2008–09) Jharkhand (1) ✓ Palamau Tiger Reserve (1973-74) F o l l o w u s : YouTube, Website, Telegram, Instagram, Facebook. -

Published on Sep 24 2015 3:37PM GOVERNMENT OF

Published Sep 24 2015 3:37PM GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA on PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT P.W. DIVISION , ALLAPALLI Tender Notice No NGP/GAD/ALP/09 for Year 2015-2016 Sealed tender for the following works are invited by the Executive Engineer, Public Works Division , Allapalli, Public Works Division , Aheri Road, Allapalli. Taluka-Aheri District-Gadchiroli Tel. No.-07133:266402 from the Contractors registered with the Government of Maharashtra in appropriate class. The blank tender forms shall be issued by Executive Engineer, Public Works Division , Allapalli from 24/9/2015 to 19/10/2015 during office hours. Sealed tender forms will be received by the authority mentioned in the table below. Time limit Type&Cost Estimated cost Earnest for Class of Tender Receiving Name of Work of Tender Pre Bid Details Rs. Money Rs. completion contractor Authority Form (months) improvement to allapalli hemalkasa Office of the bhamragad road Superintending Chief (sh-382) in km. Engineer Public Engineer Class 36/500 to 41/000, B-1 Works Circle, Public Works 1,77,44,330 1,34,000 06 III& (actual ch- 38/7500 5000 Gadchiroli on or Region, Above to 41/000) taluka - before 25/10/2015 Nagpur Dt. bhamragad, distt - upto 17.00 hours. 01.10.2015 @ gadchiroli. 16.00 Hrs No Attachments improvement to allapalli hemalkasa Office of the bhamragad road Superintending Chief Engineer Public Engineer (sh-382) in km. Class B-1 Works Circle, Public Works 60/00 to 63/000, 1,77,40,771 1,34,000 06 III& 5000 Gadchiroli on or Region, taluka - Above bhamragad, distt - before 25/10/2015 Nagpur Dt. -

Can Community Forestry Conserve Tigers in India?

Can Community Forestry Conserve Tigers in India? Shibi Chandy David L. Euler Abstract—Active participation of local people through community (Ontario Ministry for Natural Resources 1994). In most forestry has been successful in several developed countries. In the developing countries, like India, the socio-economic prob- early 1980’s, developing countries tried to adopt this approach for lems will have to be addressed first to achieve the objectives the conservation and management of forests. Nepal, for example, of conservation (Kuchli 1997). has gained considerable support from local people by involving them Royal Bengal Tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) (fig. 1) are in conservation policies and actions. This paper illustrates that endangered and almost on the verge of extinction. Conser- people living near the Sundarbans Tiger Reserve/National Park in vation of these animals in Asia poses serious problems, as India should not be considered mere gatherers of forest products. their population has been reduced significantly due to They can also be active managers and use forest resources hunting, poaching, and habitat shrinkage. Reserves and sustainably, which will help in the conservation of tigers. parks have been established to protect the animals and separate people from the forests. This, however, has caused Conservation of tigers in Asia, especially in India, is a major concern. The Sundarbans offers a unique habitat for tigers, but the conservation strategies followed for the past 20 years have not yielded much result. One of the major reasons is that local people and their needs were ignored. Lack of concern for the poverty/forest interface, which takes a heavy toll on human lives, is another reason for failure. -

Pench Tiger Reserve: Maharashtra

Pench Tiger Reserve: Maharashtra drishtiias.com/printpdf/pench-tiger-reserve-maharashtra Why in News Recently, a female cub of 'man-eater' tigress Avni has been released into the wild in the Pench Tiger Reserve (PTR) of Maharashtra. Key Points About: It is located in Nagpur District of Maharashtra and named after the pristine Pench River. The Pench river flows right through the middle of the park. It descends from north to south, thereby dividing the reserve into equal eastern and western parts. PTR is the joint pride of both Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. The Reserve is located in the southern reaches of the Satpura hills in the Seoni and Chhindwara districts in Madhya Pradesh, and continues in Nagpur district in Maharashtra as a separate Sanctuary. It was declared a National Park by the Government of Maharashtra in 1975 and the identity of a tiger reserve was granted to it in the year 1998- 1999. However, PTR Madhya Pradesh was granted the same status in 1992-1993. It is one of the major Protected Areas of Satpura-Maikal ranges of the Central Highlands. It is among the sites notified as Important Bird Areas (IBA) of India. The IBA is a programme of Birdlife International which aims to identify, monitor and protect a global network of IBAs for conservation of the world’s birds and associated diversity. 1/3 Flora: The green cover is thickly spread throughout the reserve. A mixture of Southern dry broadleaf teak forests and tropical mixed deciduous forests is present. Shrubs, climbers and trees are also frequently present. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Coverage Report on Reliance General Insurance Empowers

Coverage Report On Reliance General Insurance empowers customers with a rapid vehicle claims solution powered by Microsoft Azure AI PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE Sr. Publication Headline Pg. Edition/Links No. No. 1 The Hindu Reliance Insurance's Al solution 9 Ahmedabad Business line Delhi Chandigarh Bengaluru Hyderabad Chennai Kochi Mumbai Kolkata Pune 2 Loksatta Auto insurance now in one hour 4 Mumbai 3 Herald Reliance General Insurance empowers 7 Ahmedabad Youngleader customers with a rapid vehicle claims solution powered by Microsoft Azure AI 4 Arthik Lipi Reliance General Insurance introduced 9 Kolkata the entire insurance ID of the claim 5 Navbharat Rapid service started 5 Mumbai 6 Saamana The vehicle accident claim was easy 5 Mumbai 7 Central Reliance General Insurance providing 7 Bhopal Chronicle Microsoft Azure AI 8 Divya Bhaskar Quick vehicle claims settlement 4 Mumbai 9 Duniya ^Reliance General Insurance empowers 7 Bhubaneshwar Khabar customers with a rapid vehicle claims solution powered by microsoft Azure AI^ 10 Dainik Reliance General Insurance is 5 Jaipur Adhikar empowering customers to settle vehicle claims immediately 11 Jagruk Times Reliance General Insurance is 4 Jaipur empowering customers with Microsoft Azure AI solution 12 Indian Era RGI empowers customers with a rapid 7 Bhubaneshwar vehicle claims 13 Uttar Shakti Reliance General Insurance is 3 Mumbai empowering customers with Microsoft Azure AI solution 14 Vyapar Reliance General Insurance launched IoA 3 Mumbai based solution 15 Jagruk Times The vehicle accident claim was -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

National Tiger Conservation Authority Ministry of Environment & Forests

F. No. 3-1/2003-PT REVISED GUIDELINES FOR THE ONGOING CENTRALLY SPONSORED SCHEME OF PROJECT TIGER FEBRUARY, 2008 National Tiger Conservation Authority Ministry of Environment & Forests Government of India 1 Government of India Ministry of Environment & Forests National Tiger Conservation Authority REVISED GUIDELINES FOR THE ONGOING CENTRALLY SPONSORED SCHEME OF PROJECT TIGER (1) Introduction: Project Tiger is an ongoing Centrally Sponsored Scheme of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. The revised guidelines incorporate the additional activities for implementing the urgent recommendations of the Tiger Task Force, constituted by the National Board for Wildlife, chaired by the Hon’ble Prime Minister. These, interalia, also include support for implementing the provisions of the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006, which has come into force with effect from 4.09.2006. The activities are as below: (i) Antipoaching initiatives (ii) Strengthening infrastructure within tiger reserves (iii) Habitat improvement and water development (iv) Addressing man-animal conflicts (v) Co-existence agenda in buffer / fringe areas with landscape approach (vi) Deciding inviolate spaces and relocation of villages from crucial tiger habitats within a timeframe by providing a better relocation package, apart from supporting States for settlement of rights of such people (vii) Rehabilitation of traditional hunting tribes living in and around tiger reserves (viii) Providing support to States for research and field equipments (ix) Supporting States for staff development and capacity building in tiger reserves. (x) Mainstreaming wildlife concerns in tiger bearing forests outside tiger reserves, and fostering corridor conservation in such areas through restorative strategy involving local people to arrest fragmentation of habitats. -

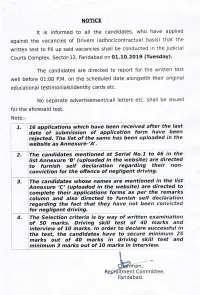

DRIVER LIST and NOTICE for WRITTEN EXAMINATION.Pdf

COMBINE Annexure-A Reject List of applications for the post of Driver August -2019 ( Ad-hoc) as received after due date 20/08/19 Date of Name of Receipt No. Father's / Husband Name Address of the candidate Contact No. Date of Birth Remarks Receipt Candidate Vill-Manesar, P.O Garth Rotmal Application 1 08/21/19 Yogesh Kumar Narender Kumar Teh- Ateli Distt Mohinder Garh 10/29/93 Received after State Haryana 20.08.2019 Khor PO Ateli Mandi Teh Ateli, Application 2 08/21/19 Pankaj Suresh Kumar 9818215697 12/20/93 Received after distt mahendergarh 20.08.2019 Amarjeet S/O Krishan Kumar Application 3 08/21/19 Amarjeet Kirshan Kumar 05/07/92 Received after VPO Bhikewala Teh Narwana 20.08.2019 121, OFFICER Colony Azad Application 4 08/21/19 Bhal Singh Bharat Singh nagar Rajgarh Raod, Near 08/14/96 Received after Godara Petrol Pump Hissar 20.08.2019 Vill Hasan, Teh- Tosham Post- Application 5 08/21/19 Rakesh Dharampal 10/15/97 Received after Rodhan (Bhiwani) 20.08.2019 VPO Jonaicha Khurd, Teh Application 6 08/21/19 Prem Shankar Roshan Lal Neemarana, dist Alwar 12/30/97 Received after (Rajasthan) 20.08.2019 VPO- Bhikhewala Teh Narwana Application 7 08/21/19 Himmat Krishan Kumar 09/05/95 Received after Dist Jind 20.08.2019 vill parsakabas po nagal lakha Application 8 08/21/19 Durgesh Kumar SHIMBHU DAYAL 09/05/95 Received after teh bansur dist alwar 20.08.2019 RZC-68 Nihar Vihar, Nangloi New Application 9 08/26/19 Amarjeet Singh Mohinder Singh 03/17/92 Received after Delhi 20.08.2019 Vill Palwali P.O Kheri Kalan Sec- Application 10 08/26/19 Rohit Sharma -

Indira Charity Cell

Indira Charity Cell C/O Shree Chanakya Education Society , S/No. 85 / 5A , New Pune - Mumbai Highway , Near Wakad Police Chowky , Tathawade , Pune - 411033 . SR. NAME ADDRESS & CONTACT NO. GROUND AMOUNT BANK CH. NO. No. ( Rs.) DATE 1 Mr. Sanjay Ishwar Shinde S/No. 14 B , Koregaon Park , Darwademala , Medical 11, 000 BOM / 240176 Pune - 411001 . ( 9860519144 / 9890078021 ) 3/7/2007 2 Ms. Minakshi Mohan Thosar 20 , Suchetanagar , Kedgaon , Ahmednagar - Education 11, 000 BOM / 997078 414 005 . ( 0241 - 2550430 ) 13/9/2007 3 Mrs. Nirmalatai Sovani The Trustee & Secretary , David Sassoon Social 51, 000 BOM / 266649 Infirm Asylum , Niwara , 96 Sadashiv ( Navi ) Charity 26/9/2007 Peth , Pune - 411 030 . ( 24328429 ) 4 Mr. Shivlal Jadhav The President , Bhatkya Vimuct Jati Shikshan Social 51, 000 BOM / 266648 Sanstha , Sarvoday Colony , Mundhwa , Charity 26/9/2007 Pune - 411 036 . ( 9325500100 / 2412550430 ) 5 Mr. Ramesh Chaburao Rahatal Scholarship to Student Mr. Sunny , MBA - I , Education 20, 000 Adjusted agnst Div - A , Roll No. 49 ( 2007 - 08 ) ( 9860407666 ) CDP Fees . 6 Smt. Ujwala Lawate The Managing Trustee , Manavya , Social 50, 000 BOM / 278857 46/3/1 , Laxman Villa , Flat No. 13 , Charity 29/11/2007 3rd Floor , Paud Road , Pune - 411038 . ( 25422282 / 32302688 / 9370547072 ) 7 Mrs. Meena Inamdar The President , Jeevan Jyot Mandal , Social 50, 000 BOM / 278858 Plot No. 62 , Tarate Colony , Karve Road , Charity 29/11/2007 Karve Road , Pune - 411 004 . ( 25463259 / 25652101 ) 8 Mr. Danial Gajbheev The President , Handicap Welfare Association Social 50, 000 BOM / 278856 G - 7 , Ganga Residency , Opp. Talegaon Kach Charity 29/11/2007 Karkhana , Chakan Road , Talegaon - Dabhade . -

Asian Ibas & Ramsar Sites Cover

■ INDIA RAMSAR CONVENTION CAME INTO FORCE 1982 RAMSAR DESIGNATION IS: NUMBER OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 19 Complete in 11 IBAs AREA OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 648,507 ha Partial in 5 IBAs ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITY FOR RAMSAR CONVENTION Special Secretary, Lacking in 159 IBAs Conservation Division, Ministry of Environment and Forests India is a large, biologically diverse and densely populated pressures on wetlands from human usage, India has had some country. The wetlands on the Indo-Gangetic plains in the north major success stories in wetland conservation; for example, of the country support huge numbers of breeding and wintering Nalabana Bird Sanctuary (Chilika Lake) (IBA 312) was listed waterbirds, including high proportions of the global populations on the Montreux Record in 1993 due to sedimentation problem, of the threatened Pallas’s Fish-eagle Haliaeetus leucoryphus, Sarus but following successful rehabilitation it was removed from the Crane Grus antigone and Indian Skimmer Rynchops albicollis. Record and received the Ramsar Wetland Conservation Award The Assam plains in north-east India retain many extensive in 2002. wetlands (and associated grasslands and forests) with large Nineteen Ramsar Sites have been designated in India, of which populations of many wetland-dependent bird species; this part 16 overlap with IBAs, and an additional 159 potential Ramsar of India is the global stronghold of the threatened Greater Sites have been identified in the country. Designated and potential Adjutant Leptoptilos dubius, and supports important populations Ramsar Sites are particularly concentrated in the following major of the threatened Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis, Lesser wetland regions: in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, two designated Adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus, White-winged Duck Cairina Ramsar Sites overlap with IBAs and there are six potential scutulata and wintering Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri.