Confederates in OUR Attic a Campus Conversation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kentucky in the 1880S: an Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R

The Kentucky Review Volume 3 | Number 2 Article 5 1982 Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R. Ford University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ford, Thomas R. (1982) "Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography* e c Thomas R. Ford r s F t.; ~ The early years of a decade are frustrating for social demographers t. like myself who are concerned with the social causes and G consequences of population changes. Social data from the most recent census have generally not yet become available for analysis s while those from the previous census are too dated to be of current s interest and too recent to have acquired historical value. That is c one of the reasons why, when faced with the necessity of preparing c a scholarly lecture in my field, I chose to stray a bit and deal with a historical topic. -

Captain Thomas Jones Gregory, Guerrilla Hunter

Captain Thomas Jones Gregory, Guerrilla Hunter Berry Craig and Dieter Ullrich Conventional historical wisdom long held that guerrilla warfare had little effect on the outcome of America's most lethal conflict. Hence, for years historians expended relatively Little ink on combat between these Confederate marauders and their foes-rear-area Union troops, state militia and Home Guards. But a handful of historians, including Daniel Sutherland, now maintain that guerrilla warfare, most brutal and persistent in border state Missouri and Kentucky, was anything but an adjunct to the wider war. "It is impossible to understand the Civil War without appreciating the scope and impact of the guerrilla conflict," Sutherland argued in A Savage Confl,ict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the Civil War (2009). "That is no easy thing to do," he conceded, because guerrilla warfare was "intense and sprawling, born in controversy, and defined by all variety of contradictions, contours, and shadings." 1 Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic of China, is arguably the most famous and most successful guerrilla leader in history. "Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy's rear," he wrote in 193 7 while fighting Japanese invaders. "Such a belief reveals lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water the latter to the fish who inhabit it. "2 Guerrilla "fish" plagued occupying Union forces in the Jackson Purchase, Kentucky's westernmost region, for most of the war because the "water" was welcoming. -

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 Lrrs N and S

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 LRRs N and S Brad D. Lee and John M. Kabrick 12.1 Introduction snowfall occurs annually in the Ozark Highlands, the Springfield Plateau, and the St. Francois Knobs and Basins The central, unglaciated US east of the Great Plains to the MLRAs. In the southern half of the region, snowfall is Atlantic coast corresponds to the area covered by LRR N uncommon. (East and Central Farming and Forest Region) and S (Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region). These regions roughly correspond to the Interior Highlands, Interior Plains, 12.2.2 Physiography Appalachian Highlands, and the Northern Coastal Plains. The topography of this region ranges from broad, gently rolling plains to steep mountains. In the northern portion of 12.2 The Interior Highlands this region, much of the Springfield Plateau and the Ozark Highlands is a dissected plateau that includes gently rolling The Interior Highlands occur within the western portion of plains to steeply sloping hills with narrow valleys. Karst LRR N and includes seven MLRAs including the Ozark topography is common and the region has numerous sink- Highlands (116A), the Springfield Plateau (116B), the St. holes, caves, dry stream valleys, and springs. The region also Francois Knobs and Basins (116C), the Boston Mountains includes many scenic spring-fed rivers and streams con- (117), Arkansas Valley and Ridges (118A and 118B), and taining clear, cold water (Fig. 12.2). The elevation ranges the Ouachita Mountains (119). This region comprises from 90 m in the southeastern side of the region and rises to 176,000 km2 in southern Missouri, northern and western over 520 m on the Springfield Plateau in the western portion Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

Buckland History

HISTORIC SITE FILE: Bu ti< LftAl D PRINCE WILLIAM PVBUC LIBRARY SYSTEM RELIC/Bull Run Reg Lib Manassas, VA Buckland History Prior to the establishment of Buckland Towne in 1798, this same site, on the banks of Broad Run, was a thriving prehistoric, Native American settlement. The first recorded deeds make reference to the "Indian Springs". There were five springs, which indicates a rather large Indian population. Jefferson Street, that bisects the village of Buckland, was once known as the Iroquois Trail. (Record of this Trail appears in 1662, when Col. Abraham Wood, a noted surveyor of his day, reported that "the Susquehannoc Indians would leave their main village about forty miles up the Susquehanna River; make their way to Point of Rocks, thence down into North Carolina, where they would barter with Indians on the Yadkin River for beaver skins, then return to New Amsterdam and sell their skins to the Dutch".) After the Treaty of Albany was signed in 1722, the trail be~ame known as the Carolina Trail or Road. This location on the banks of Broad Run with a never failing, swift flow of water, proved to be as desirable to the European settlers but, rather for the establishment of mills. The land at Buckland was originally part of the Broad Run Tract owned by Robert (King) Carter and after his death, his sons, Landon and Charles, deeded the tract in 1771 to brother-in-law Walker Taliaferro. The Carter family had operated a Mill here in the early 177o's when the property was conveyed in 1774 to Samuel Love "together with the mill built and erected thereon and the land mill dam and other appurtenances used with said mill". -

September 2020

View as Webpage September 2020 Neighbors, While the past six months of COVID times have brought much change and challenge to our lives, they have also brought a change of pace. Many are finding more time to spend with their families, visit our parks, take a walk in the neighborhood or ride our many bike trails throughout the County. Personally, one of my wife Deb’s and my new favorite activities is to grab a sandwich from a local restaurant along with our lawn chairs and head to the river to enjoy a picnic in the park. Now, with fall upon us, I expect we will see even more of our friends and neighbors enjoying opportunities like these. This change of pace and activity also remind us of the importance of parks in our communities. The November election ballot will include a parks bond that I hope you will support. Projects in our area include: a second sheet of ice at Mount Vernon RECenter, renewal of Lee District RECenter, design improvements for the South Run RECenter, phase one of construction for an archaeology-and-collections facility in Lorton and improvements for the Laurel Hill Golf Course and Mount Vernon Woods Park. These are in addition to funding for system-wide renovations and life-cycle needs for playgrounds, irrigation and lighting systems, restrooms, picnic shelters, bridges and trails. With the increase in bicycle riders on our trails and streets, this is a perfect year to join the Tour de Mount Vernon Community Bike Ride on October 3, 2020. With 35-mile and 20-mile options, this ride is very accessible for most and an excellent opportunity to see many of the outdoor highlights of the southern portion of the District. -

A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800 Wendy Sacket College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sacket, Wendy, ""Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625418. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ypv2-mw79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PEOPLING THE WESTERN COUNTRY": A STUDY OF MIGRATION FROM AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, TO KENTUCKY, 1777-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wendy Ellen Sacket 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December, 1987 John/Se1by *JU Thad Tate ies Whittenburg i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. iv LIST OF T A B L E S ...............................................v LIST OF MAPS . ............................................. vi ABSTRACT................................................... v i i CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERATURE, PURPOSE, AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT STUDY . -

Some Revolutionary War Soldiers Buried in Kentucky

Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Perryville Casualty Pink Things: Some Revolutionary Database Reveals A Memoir of the War Soldiers Buried True Cost of War Edwards Family of in Kentucky Harrodsburg Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Thomas E. Stephens, Editor kentucky ancestors Dan Bundy, Graphic Design Kent Whitworth, Director James E. Wallace, Assistant Director administration Betty Fugate, Membership Coordinator research and interpretation Nelson L. Dawson, Team Leader management team Kenneth H. Williams, Program Leader Doug Stern, Walter Baker, Lisbon Hardy, Michael Harreld, Lois Mateus, Dr. Thomas D. Clark, C. Michael Davenport, Ted Harris, Ann Maenza, Bud Pogue, Mike Duncan, James E. Wallace, Maj. board of Gen. Verna Fairchild, Mary Helen Miller, Ryan trustees Harris, and Raoul Cunningham Kentucky Ancestors (ISSN-0023-0103) is published quarterly by the Kentucky Historical Society and is distributed free to Society members. Periodical postage paid at Frankfort, Kentucky, and at additional mailing offices. Postmas- ter: Send address changes to Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. Please direct changes of address and other notices concerning membership or mailings to the Membership De- partment, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931; telephone (502) 564-1792. Submissions and correspondence should be directed to: Tom Stephens, editor, Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Histori- cal Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. The Kentucky Historical Society, an agency of the Commerce Cabinet, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, or disability, and provides, on request, reasonable accommodations, includ- ing auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs, and activities. -

The Political Process in Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 3 Article 1 1957 The olitP ical Process in Kentucky Jasper Shannon University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Law and Politics Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Shannon, Jasper (1957) "The oP litical Process in Kentucky," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 45 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol45/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Political Process in Kentucky By JASPER SHANNON* CircumstancesPeculiar to Kentucky The roots of law are deeply embedded in politics. Nowhere is this more true than in Kentucky. Law frequently is the thin veneer which reason employs in a ceaseless but unsuccessful effort to control the turbulence of emotion. Born in the troubled era of the American and French Revolutions, Kentucky was in addition exposed to four years of bitter civil violence when nationalism and sectionalism struggled for supremacy (1861-65). Kentucky, ac- cordingly, within her borders has known in its most intense form the heat of passion which so often supplants reason in the clash of interests forming the heart of legal and political processes. Too many times in its colorful history the forms of law have broken down in the conflict of emotions. -

Early History of Thoroughbred Horses in Virginia (1730-1865)

Early History of Thoroughbred Horses in Virginia (1730-1865) Old Capitol at Williamsburg with Guests shown on Horseback and in a Horse-drawn Carriage Virginia History Series #11-08 © 2008 First Horse Races in North America/Virginia (1665/1674) The first race-course in North America was built on the Salisbury Plains (now known as the Hempstead Plains) of Long Island, New York in 1665. The present site of Belmont Park is on the Western edge of the Hempstead Plains. In 1665, the first horse racing meet in North America was held at this race-course called “Newmarket” after the famous track in England. These early races were match events between two or three horses and were run in heats at a distance of 3 or 4 miles; a horse had to complete in at least two heats to be judged the winner. By the mid-18th century, single, "dash" races of a mile or so were the norm. Virginia's partnership with horses began back in 1610 with the arrival of the first horses to the Virginia colonies. Forward thinking Virginia colonists began to improve upon the speed of these short stocky horses by introducing some of the best early imports from England into their local bloodlines. Horse racing has always been popular in Virginia, especially during Colonial times when one-on-one matches took place down village streets, country lanes and across level pastures. Some historians claim that the first American Horse races were held near Richmond in Enrico County (now Henrico County), Virginia, in 1674. A Match Race at Tucker’s Quarter Paths – painting by Sam Savitt Early Racing in America Boston vs Fashion (The Great Match Race) Importation of Thoroughbreds into America The first Thoroughbred horse imported into the American Colonies was Bulle Rock (GB), who was imported in 1730 by Samuel Gist of Hanover County, Virginia. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

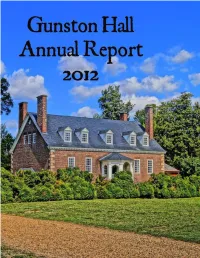

Annual Report 2012.Pub

FFFROM THE FIRST REGENT OVER THE PAST EIGHT YEARS , the plantation of George Mason enjoyed meticulous restoration under the directorship of David Reese. Acclaim was univer- sal, as the mansion and outbuildings were studied, re- paired, and returned to their original stature. Contents In response to the voices of community, staff, docents From the First Regent 2 and the legislature, the Board of Regents decided in early 2012 to focus on programming and to broadened interac- 2012 Overview 3 tion with the public. The consulting firm of Bryan & Jordan was engaged to lead us through this change. The work of Program Highlights 4 the Search Committee for a new Director was delayed while the Regents and the Commonwealth settled logistics Education 6 of employment, but Acting Director Mark Whatford and In- terim Director Patrick Ladden ably led us and our visitors Docents 7 into a new array of activity while maintaining the program- ming already in place. Archaeology 8 At its annual meeting in October the Board of Regents adopted a new mission statement: Seeds of Independence 9 To utilize fully the physical and scholarly resources of Museum Shop 10 Gunston Hall to stimulate continuing public exploration of democratic ideals as first presented by Staff & GHHIS 11 George Mason in the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Budget 12 The Board also voted to undertake a strategic plan for the purpose of addressing the new mission. A Strategic Funders and Donors 13 Planning Committee, headed by former NSCDA President Hilary Gripekoven and comprised of membership repre- senting Regents, staff, volunteers, and the Commonwealth, promptly established goals and working groups. -

Nomination Form

(Rev. 10-90) NPS Form 10-900 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the infonnation requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Temple Hall other names/site mrmber Temple Hall Farm Regional Park; VDHR File No. 053-0303 2. Location street & number 15764 Temple Hall Lane not for publication NIA city or town____________________________ vicinity_...;;X;..;;.... ___ state Virginia code VA county__ L_ou_d_o_un ____ code 107 Zip _2_0_1_7_6 ______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property b considered significant_ nationally_ statewide _x_ locally.