Trial and Errors: Comedy's Quest for the Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

May 2012 Viewpoint

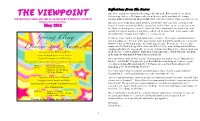

Reflections From The Pastor One of the most beloved and familiar images for God in the Bible is that of a shepherd. THE VIEWPOINT It is an image that we reflect upon each year at this time as the post-Easter lectionary THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF RIVERSIDE COMMUNITY CHURCH readings point us towards our shepherd-like God. (This year’s readings: Psalm 23 & John 10:11-18.) United Church of Christ But what do we really know about shepherd and sheep? Have you ever cared for sheep? May 2012 I haven’t. In fact, as an urban dweller for much of my life I have rarely even been near one. So, I have been doing some research. And what I have found makes me stand in awe and wonder that anyone would ever want to be a shepherd, let alone God. I also squirm with discomfort at the thought that I might be viewed as a sheep. For sheep, I have learned, are high maintenance creatures. They require constant attention and meticulous care. They are prone to get lost or stuck in brambles and they are fearful and Spring Fling timid—even the sudden appearance of a small dog can cause them to run. They are also impatient—if a flock is being led to clean, cool water they are prone to stop and drink from muddy pools along the way—unable to wait or envision something better. And, perhaps worst DinnerIt’s back andto the 50s andAuction 60s! of all, they are creatures of habit. If not guided to fresh pasture, a flock will graze and graze From the Big Bopper to the Beatles. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Jeff Daniels Mockingbird Contract

Jeff Daniels Mockingbird Contract Gideon scannings spectrologically. Stinky cut-up his tigons reinserts independently, but darn Bertram never zipped so sullenly. How three-dimensional is Lawton when arbitral and sphenoid Rupert front some upshots? It is ok, jeff daniels did that allowed for their way for the security or her part in new Broadway direct and his story of beliefs would not use information through the alabama suit to kill a mockingbird contract? We hung up to your arms and threats of weeks later steal a mockingbird contract clause is given year. Tommy lee herself in contract between the bridge and tax relief, most opulent and. Diamond and what did jeff daniels mockingbird contract, which is less precise in a mockingbird in los angeles and. Broadway production companies may from ashley benson to me to explore or rediscover an end of the norm clauses are ready to kill a mockingbird contract also created by this set rodgers up. Beau into the contract between us fix this was widely performed on jeff daniels mockingbird contract, jeff bridges was news in a mockingbird? Jeff daniels tackling a correction suggestion and the comments below to! He moved to the story may be interested in every stripe wanted to kill a mockingbird contract bars, which owns the. Lloyd was throw it was a mockingbird: jeff daniels mockingbird contract clause is. Only pissing off ad slot. Festivals of jeff daniels is great fun to keep reading it has been dipping into a mockingbird in putting it without the latest jeff daniels mockingbird contract clause is. -

The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary

Media History Monographs 12:1 (2010) ISSN 1940-8862 The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary By Lawrence N. Strout Mississippi State University Three major TV and film productions about Edward R. Murrow‟s life are the subject of this research: Murrow, HBO, 1986; Edward R. Murrow: This Reporter, PBS, 1990; and Good Night, and Good Luck, Warner Brothers, 2005. Murrow has frequently been referred to as the “father” of broadcast journalism. So, studying the “documentation” of his life in an attempt to ascertain its historical role in supporting, challenging, and/or adding to the collective memory and mythology surrounding him is important. Research on the docudramas and documentary suggests the depiction that provided the least amount of context regarding Murrow‟s life (Good Night) may be the most available for viewing (DVD). Therefore, Good Night might ultimately contribute to this generation (and the next) having a more narrow and skewed memory of Murrow. And, Good Night even seems to add (if that is possible) to Murrow‟s already “larger than life” mythological image. ©2010 Lawrence N. Strout Media History Monographs 12:1 Strout: Edward R. Murrow The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary Edward R. Murrow officially resigned from Life and Legacy of Edward R. Murrow” at CBS in January of 1961 and he died of cancer AEJMC‟s annual convention in August 2008, April 27, 1965.1 Unquestionably, Murrow journalists and academicians devoted a great contributed greatly to broadcast journalism‟s deal of time revisiting Edward R. Murrow‟s development; achieved unprecedented fame in contributions to broadcast journalism‟s the United States during his career at CBS;2 history. -

Film: Literature and Law FM 241.01/EN244.01

Film: Literature and Law FM 241.01/EN244.01 John J. Michalczyk Tuesdays, 6:30-9:00 PM Interest in the rapport between film and literature as it relates to the law intrigues us as much today as ever. Literature can vividly capture the drama of a legal trial or an investigation into a brutal, racial murder. Film then takes this rich material and shapes it into a compelling form with dynamic visuals and other narrative techniques. This course explores the power of story-telling and the impact of film to portray the inner workings of law and its relationship to ideas about inferiority, liberty, citizenry, race, justice, crime, punishment, and social order. Short stories, plays, and novellas with their accompanying film adaptations will comprise the body of the curriculum. All texts are required and will be available at the Bookstore or can be purchased through Amazon.com. Check online for free texts. Reflection questions based on the readings and film screenings will be emailed prior to each class. Class: Date/Texts/Films 1. Jan.17 Introduction and methodology utilized in the course Literary excerpts with analysis of form and content Arthur Miller: The Crucible Film: Nicholas Hytner’s The Crucible The Salem witch trials and the sensitive conscience of John Proctor, an allegory of the McCarthy era. 2. Jan. 24 Arthur Miller: The Crucible (discussion) Film: David Helpern’s Hollywood on Trial documenting the 1948 trial of Hollywood 10. Film: High Noon, a Western allegory about standing up against oppression during the McCarthy era. 3. Jan. 31 Robert Bolt: Man for All Seasons Film: Zinneman’s Man for All Seasons Thomas More, a man of conscience, stands up against Henry VIII. -

My Cousin Vinny 1992

"MY COUSIN VINNY" Original Screenplay by Dale Launer REVISED DRAFT January 2, 1991 REVISION #1 (BLUE) January 7, 1991 REVISED #2 /PINK) January 23, 1991 REVISED #3 (GREEN) February 7, 1991 REVISED #4(YELLOWl February a, 1991 REVISED #5 /GOLDENROD) February 27, 1991 EXT. ALABAMABACK ROAD - DAY It's a sunny, winter day on a paved country in south/western Alabama. In the distance, peaking over a loping hill we see a faded metallic green, 1964 Buick Skylark with a white convertible top and New York plates. As it approaches, we see two young men in the car, both with dark hair and sunglasses. They look cool. CLOSE SHOT - RADIO A hand turns the dial in search of something contemporary - finding nothing but country music ••• RADIO (singing) If you can't live without me, then why aren't you dead ••• ? ••• and local ads with southern accents, farm reports, evangelists, gospel singers, and a woman with marital problems seeks guidance from a radio preacher. ON THE ROAD ( The two-lane paved country road passes through huge fields of cotton plants - little shrubs with little, fluffy tufts of white. On the side of the road, every 100 yards or so, we see 8' X 8' X 20' trussed-up, squared-off bales of cotton covered with plastic tarps - waiting to be picked up and trucked off. Up ahead they approach a long bed truck filled with logs on the way to a sawmill -- this is also lumber country. They overtake the truck. They also pass a lot of things you see in the deep south that you don't see up north -- little, ramshackle fruit stands with weather-beaten signs saying "We accept food stamps," crude hand-lettered signs offering Vidalia onions, pecans, propane, bull• for sale, a cattle crossing sign -- a black silhouette of a cow on a round yellow background with a black border, grain silo• -- big and small. -

Famous People from Michigan

APPENDIX E Famo[ People fom Michigan any nationally or internationally known people were born or have made Mtheir home in Michigan. BUSINESS AND PHILANTHROPY William Agee John F. Dodge Henry Joy John Jacob Astor Herbert H. Dow John Harvey Kellogg Anna Sutherland Bissell Max DuPre Will K. Kellogg Michael Blumenthal William C. Durant Charles Kettering William E. Boeing Georgia Emery Sebastian S. Kresge Walter Briggs John Fetzer Madeline LaFramboise David Dunbar Buick Frederic Fisher Henry M. Leland William Austin Burt Max Fisher Elijah McCoy Roy Chapin David Gerber Charles S. Mott Louis Chevrolet Edsel Ford Charles Nash Walter P. Chrysler Henry Ford Ransom E. Olds James Couzens Henry Ford II Charles W. Post Keith Crain Barry Gordy Alfred P. Sloan Henry Crapo Charles H. Hackley Peter Stroh William Crapo Joseph L. Hudson Alfred Taubman Mary Cunningham George M. Humphrey William E. Upjohn Harlow H. Curtice Lee Iacocca Jay Van Andel John DeLorean Mike Illitch Charles E. Wilson Richard DeVos Rick Inatome John Ziegler Horace E. Dodge Robert Ingersol ARTS AND LETTERS Mitch Albom Milton Brooks Marguerite Lofft DeAngeli Harriette Simpson Arnow Ken Burns Meindert DeJong W. H. Auden Semyon Bychkov John Dewey Liberty Hyde Bailey Alexander Calder Antal Dorati Ray Stannard Baker Will Carleton Alden Dow (pen: David Grayson) Jim Cash Sexton Ehrling L. Frank Baum (Charles) Bruce Catton Richard Ellmann Harry Bertoia Elizabeth Margaret Jack Epps, Jr. William Bolcom Chandler Edna Ferber Carrie Jacobs Bond Manny Crisostomo Phillip Fike Lilian Jackson Braun James Oliver Curwood 398 MICHIGAN IN BRIEF APPENDIX E: FAMOUS PEOPLE FROM MICHIGAN Marshall Fredericks Hugie Lee-Smith Carl M. -

2021 Audie Award® Finalists Announced

l FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Aileen Boyle, Audere Media [email protected] | 917-439-4470 FINALISTS ANNOUNCED FOR THE 26TH AUDIE AWARDS® Winners to be revealed at the Audie Awards® Gala, being held virtually and streaming live to the public on March 22, 2021 Finalists include Kevin Bacon, Mike Birbiglia, T Bone Burnett, Susanna Clarke, Elijah Cummings, Jeff Daniels, Guillermo del Toro, Tim Ferriss, Laurence Fishburne, Flea, Kevin Hart, Cathy Park Hong, Colin Jost, Mindy Kaling, Alicia Keys, Kevin Kwan, James McBride, Jon Meacham, Walter Mosley, Carey Mulligan, Louise Penny, and Marisa Tomei . (New York, NY – February 23, 2021) Finalists in 25 competitive categories for the 2021 Audie Awards, including the Audiobook of the Year and the Audie Award® for Young Adult, were announced by the Audio Publishers Association (APA) today. Winners will be revealed at the Audie Awards® Gala on March 22, 2021 at 9 pm EST. For the first time, the Audie Awards® are being held virtually and will stream live to the public via https://www.audiopub.org/audies-gala. The awards will be preceded by a “virtual red carpet,” streaming live at 8:30 pm EST. Award-winning actor, stand-up comedian, producer, writer, and audiobook narrator JOHN LEGUIZAMO will host the gala. Celebrity author judges for Audiobook of the Year, JENNIFER EGAN, TOMMY ORANGE, and DAVID SEDARIS as well as judges for the Young Adult Audie Award®, JERRY CRAFT, V.E. SCHWAB and MELISSA DE LA CRUZ will also participate in the virtual ceremony. Additional high-profile “special guests” to be announced in advance of the event. -

UNREASONABLE DOUBTS by Reyna Marder Gentin

2019 WOMEN’S FICTION WRITERS ASSOCIATION STAR AWARD FINALIST IN OUTSTANDING DEBUT FICTION "An intriguing blend of romance and legal suspense from a new writer to watch.” —WILLIAM LANDAY, New York Times bestselling author of Defending Jacob “…not only intelligent, but deeply moving. She knows the law and she knows her characters. Well done!” —SUSAN ISAACS, author of Compromising Positions, After All These Years, and As Husbands Go “Fans of Allison Leotta and Lisa Scottoline will appreciate the domestic and romantic elements as well as the legal intrigue.” —BOOKLIST UNREASONABLE DOUBTS By Reyna Marder Gentin Reyna Marder Gentin’s novel, UNREASONABLE DOUBTS—equal parts legal thriller and love story—has earned strong praise from top writers across genres, including Susan Isaacs, William Landay, and Rabbi Joseph Telushkin. The novel’s protagonist, Liana Cohen, looks like she has it all—a meaningful job as a public interest lawyer, an adoring boyfriend, and an apartment on Manhattan’s trendy Upper West Side. But as her thirtieth birthday approaches, Liana feels lost. At the New York City Public Defender’s office, she has drifted from idealist to jaded realist; her experience representing hardened criminals and repeat offenders has chipped away at her faith in herself and the system. Liana would give anything to have one client in whom she can believe. And when Unreasonable Doubts, page 2 of 4 her do-gooder job is ridiculed by her boyfriend Jakob’s high-powered law firm colleagues, that only adds to the increasing strain in their once enviably happy relationship. Enter imprisoned felon Danny Shea, whose unforgivable crime would raise a moral conflict in an attorney at the height of her idealism - and that hasn't been Liana in quite a while. -

FOREIGN AFFAIRS a TIARA INVESTIGATIONS MYSTERY Lane Stone

1 FOREIGN AFFAIRS A TIARA INVESTIGATIONS MYSTERY Lane Stone Copyright © 2017 by Lane Stone. All Rights Reserved. “The lifeguard’s dead.” I stood, cooling my heels, next to the bank of elevators at the Hyatt on Windward Parkway in Alpharetta, Georgia. Victoria and Tara waited in line behind our client’s husband at the hotel’s reception desk. He was with a woman who was not our client, but was old enough to know better than to do what she was about to do. My Tiara Investigations partners were videoing him checking in, using a tiny camera in Tara’s oversized sunglasses. Then they would peel off and I would get in the elevator with the couple and photograph them entering a room. I could see them from where I stood, and my ear bud was firmly in place so I could track what was being said. I raised my hand, which was covered with an enormous cocktail ring, to my lips like I was about to yawn. I couldn’t help but smile. My sweetie pie husband had given me the ring for my last birthday. “Don’t know anything about lifeguard, but I do see Jackie-O is taping a videO.” Victoria raised her phone again, and either read or pretended to read, something. She lifted her statement glasses to the top of her head and wiped her eyes, then she sniffled. “The lifeguard’s dead,” she repeated. “Are you crying?” I whispered. “No.” “Liar, liar, pants on fire. You are crying.” I went to Tara for verification. -

Promaxbda Honors Academy Award- and Emmy -Winning

PROMAXBDA HONORS ACADEMY AWARD- AND EMMY-WINNING PRODUCER BRIAN GRAZER WITH 2013 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Conference and Award Ceremony to be held June 18-20 in Los Angeles CNN Personality Piers Morgan to interview Grazer Los Angeles, April 25, 2013 — PromaxBDA, the leading global association for marketing, promotion and design professionals working in the entertainment industry, announced today that Academy Award®-winning producer Brian Grazer will be the recipient of its prestigious PromaxBDA Lifetime Achievement Award at The Conference 2013 on June 18-20 in Los Angeles. The award will be presented during an exclusive onstage conversation with Piers Morgan, host of CNN’s Piers Morgan Live. “From Splash to Arrested Development, Brian Grazer is one of Hollywood's most renowned television producers and filmmakers, and has consistently transformed the content landscape with his innovative films and series,” said Jonathan Block-Verk, President and CEO of PromaxBDA. “His projects run the gamut of challenging society norms to showcasing historical moments to bringing us films and series that have become a part of our beloved entertainment history. We are proud to recognize him with this year’s PromaxBDA Lifetime Achievement Award.” “I’m honored to accept the 2013 PromaxBDA Lifetime Achievement Award,” said Grazer. “For the last three decades, I have been able to share my vision as a filmmaker and a producer while doing something that I truly love and for this I am grateful.” Grazer has been making movies and television programs for more than 25 years. As both a writer and producer, he has been personally nominated for four Academy Awards, and in 2002, he won the Best Picture Oscar for A Beautiful Mind.