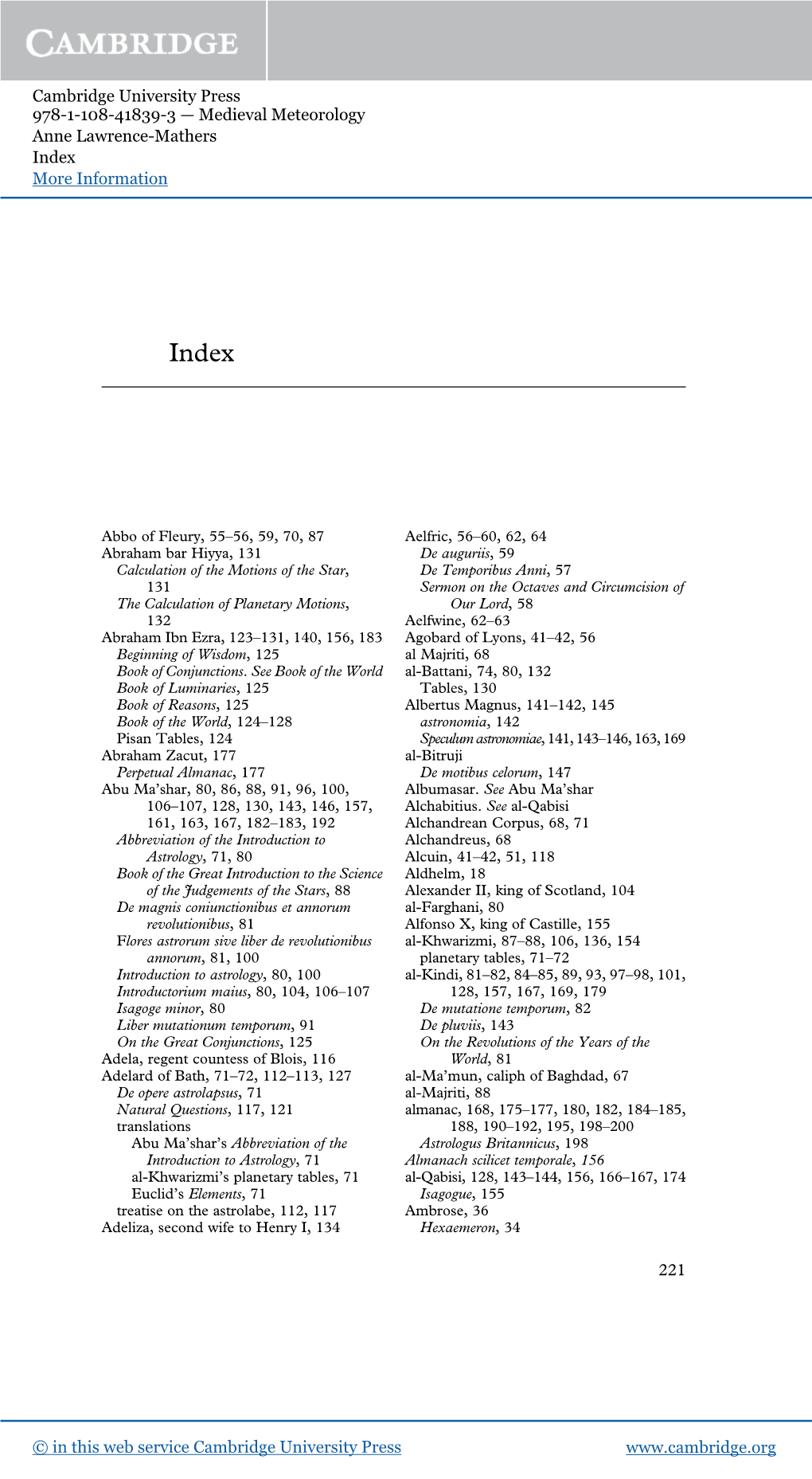

Medieval Meteorology Anne Lawrence-Mathers Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Aldus' Scriptores Astronomici (1499)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università degli Studi di... Certissima signa A Venice Conference on Greek and Latin Astronomical Texts edited by Filippomaria Pontani On Aldus’ Scriptores astronomici (1499) Filippomaria Pontani (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Elisabetta Lugato (Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venezia, Italia) Abstract The Scriptores astronomici veteres were published by Aldus Manutius in Venice 1499. This book represents the most ambitious humanist attempt to reconstruct ancient astronomical wisdom by presenting the original texts of ancient authors. As such, the volume raises several questions. What is the rationale of Aldus’ selection? What do we know about his manuscript sources and the edito- rial process? What is the history of the incunable's remarkable illustrations (most notably those in Firmicus’ books 2 and 6, and in Germanicus’ Aratea)? How does this edition fit into one of the most dificult periods of Aldus’ Venetian enterprise? This paper attempts to tackle some of these issues. Summary 1 Contents and Ordering. – 1.1 A Miscellany. – 1.2 A Bilingual Book. – 1.3 An Illustrated Book. – 1.4 From Latin to Greek, from Astrology to Astronomy. – 1.5 Relationship with Earlier Printed Editions. – 1.6 ‘Technical’ Texts and Exegesis. – 2 The Sources of the Edition. – 2.1 Firmicus Maternus. – 2.2 Manilius. – 2.3 The Aratea. – 2.4 Leontius Mechanicus. – 2.5 Aratus. – 2.6 Ps.-Proclus. – 3 Towards a General Assessment. – Appendix: Francesco Negri. Keywords Astronomy. Manuscripts. Incunables. Classical Tradition. Editorial Technique. Aldine Press. Book Illustration. Illumination. Italian Humanism. -

Preprint N°494

2019 Preprint N°494 The Reception of Cosmography in Vienna: Georg von Peuerbach, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Sebastian Binderlius Thomas Horst Published in the context of the project “The Sphere—Knowledge System Evolution and the Shared Scientific Identity of Europe” https://sphaera.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de The Reception of Cosmography in Vienna: Georg von Peuerbach, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Sebastian Binderlius Abstract In this paper, the importance of the cosmographical activities of the Vienna astronomical “school” for the reception of the Tractatus de Sphaera is analyzed. First, the biographies of two main representatives of the Vienna mathematical/astronomical circle are presented: the Austrian astronomers, mathematicians, and instrument makers Georg von Peuerbach (1423– 1461) and his student Johannes Müller von Königsberg (Regiomontanus, 1436–1476). Their studies influenced the cosmographical teaching at the University of Vienna enormously for the next century and are relevant to understanding what followed; therefore, the prosopo- graphical introductions of these Vienna scholars have been included here, even if neither can be considered a real author of the Sphaera. Moreover, taking the examples of an impressive sixteenth century miscellany (Austrian Na- tional Library, Cod. ser. nov. 4265, including the recently rediscovered cosmography by Sebastian Binderlius, compiled around 1518), the diversity of different cosmographical studies in the capital of the Habsburg Empire at the turning point between the Middle Ages and the early modern period is demonstrated. Handwritten comments in the Vienna edition of De sphaera (1518) also show how big the influence of Sacrobosco’s work remained as a didactical tool at the universities in the first decades of the sixteenth century—and how cosmographical knowledge was transformed and structured in early modern Europe by the editors and readers of the Sphaera. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 09:49:19PM This Is an Open Access Article Distributed Under the Terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License

_full_journalsubtitle: A Journal for the Study of Science, Technology and Medicine in the Pre-modern Period _full_abbrevjournaltitle: ESM _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 1383-7427 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1573-3823 (online version) _full_issue: 2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (rechter kopregel - mag alles zijn): A Medieval European Value for the Circumference of the Earth _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 A Medieval EuropeanEarly ValueScience For and The Medicine Circumference 25 (2020) 135-151 Of The Earth 135 www.brill.com/esm A Medieval European Value for the Circumference of the Earth C. Philipp E. Nothaft All Souls College, Oxford, UK [email protected] Abstract Geographic and astronomical texts from late-medieval Central Europe frequently give 16 German miles, or miliaria teutonica, as the length of a degree of terrestrial latitude. The earliest identifiable author to endorse this equivalence is the Swabian astronomer Heinrich Selder, who wrote about the length of a degree and the circumference of the Earth on several occasions during the 1360s and 1370s. Of particular interest is his claim that he and certain unnamed experimentatores established their preferred value empir- ically. Based on an analysis of relevant statements in Selder’s extant works and other late-medieval sources, it is argued that this claim is plausible and that the convention 1° = 16 German miles was indeed the result of an independent measurement. Keywords medieval geodesy – medieval astronomy – medieval metrology – circumference of the Earth – Heinrich Selder Regular readers of geographic and cartographic literature printed before 1900 will have come across the concept of the German geographic mile, which was defined as covering one fifteenth of a degree of latitude, making it equi- valent to 4 nautical miles. -

A Reconstruction of the Tables of Rheticus' Canon Doctrinæ Triangulorum (1551)

A reconstruction of the tables of Rheticus’ Canon doctrinæ triangulorum (1551) Denis Roegel To cite this version: Denis Roegel. A reconstruction of the tables of Rheticus’ Canon doctrinæ triangulorum (1551). [Research Report] LORIA (Université de Lorraine, CNRS, INRIA). 2021. inria-00543931v2 HAL Id: inria-00543931 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00543931v2 Submitted on 1 Sep 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A reconstruction of the tables of Rheticus’ Canon doctrinæ triangulorum (1551) Denis Roegel 11 January 2011 (last version: 2 September 2021) This document is part of the LOCOMAT project: http://locomat.loria.fr Quam quisque novit artem, in hac se exerceat Cicero 1 Trigonometric tables before Rheticus As told by Gerhardt in his history of mathematics in Germany, Peuerbach (1423–1461) and his pupil Regiomontanus (1436–1476) [30, 43, 85] woke up the study of astronomy and built the necessary tables [33, p. 87]. Regiomontanus calculated tables of sines for every minute of arc for radiuses of 6000000 and 10000000 units.1 Regiomontanus had also computed a table of tangents [50], but with the smaller radius R = 105 and at intervals of 1◦. -

Henry VII's Book of Astrology and the Tudor Renaissance*

Henry VII’s Book of Astrology and the Tudor Renaissance* by H ILARY M. CAREY This essay considers the place of astrology at the early Tudor court through an analysis of British Library MS Arundel 66, a manuscript compiled for the use of Henry VII (r. 1485 –1509) in the 1490s. It argues that an illustration on fol. 201 depicts King Henry being presented with prognostications by his astrologer, William Parron, with the support of Louis, Duke of Orleans, later King Louis XII of France (r. 1498 –1515). It considers the activities of three Tudor astrologer courtiers, William Parron, Lewis of Caerleon, and Richard Fitzjames, who may have commissioned the manuscript, as well as the Fitzjames Zodiac Arch at Merton College, Oxford (1497) and the London Pageants of 1501. It concludes that Arundel 66 reflects the strategic cultural investment in astrology and English prophecy made by the Tudor regime at the time of the marriage negotiations and wedding of Arthur, Prince of Wales and Katherine of Aragon, descendant of Alfonso X, the most illustrious medieval patron of the science of the stars. 1. I NTRODUCTION ritish Library MS Arundel 66 is one of the finest of all English B medieval and Renaissance scientific manuscripts.1 Indeed, John North gave it a broader international significance by suggesting that one item in the collection, a copy of the tables of the Oxford astronomer John Killingworth (d. 1445), was, possibly, ‘‘the most sumptuous astronomical tables ever penned.’’2 The manuscript has been firmly dated to the year 1490 and, since the nineteenth century, has been associated with Henry VII (r. -

Preprint N°494

2019 Preprint N°494 The Reception of Cosmography in Vienna: Georg von Peuerbach, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Sebastian Binderlius Thomas Horst Published in the context of the project “The Sphere—Knowledge System Evolution and the Shared Scientific Identity of Europe” https://sphaera.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de The Reception of Cosmography in Vienna: Georg von Peuerbach, Johannes Regiomontanus, and Sebastian Binderlius Abstract In this paper, the importance of the cosmographical activities of the Vienna astronomical “school” for the reception of the Tractatus de Sphaera is analyzed. First, the biographies of two main representatives of the Vienna mathematical/astronomical circle are presented: the Austrian astronomers, mathematicians, and instrument makers Georg von Peuerbach (1423– 1461) and his student Johannes Müller von Königsberg (Regiomontanus, 1436–1476). Their studies influenced the cosmographical teaching at the University of Vienna enormously for the next century and are relevant to understanding what followed; therefore, the prosopo- graphical introductions of these Vienna scholars have been included here, even if neither can be considered a real author of the Sphaera. Moreover, taking the examples of an impressive sixteenth century miscellany (Austrian Na- tional Library, Cod. ser. nov. 4265, including the recently rediscovered cosmography by Sebastian Binderlius, compiled around 1518), the diversity of different cosmographical studies in the capital of the Habsburg Empire at the turning point between the Middle Ages and the early modern period is demonstrated. Handwritten comments in the Vienna edition of De sphaera (1518) also show how big the influence of Sacrobosco’s work remained as a didactical tool at the universities in the first decades of the sixteenth century—and how cosmographical knowledge was transformed and structured in early modern Europe by the editors and readers of the Sphaera.