COMMUNITY in AUGUST WILSON and TONY KUSHNER By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

American Players Theatre August Wilson's FENCES 2019 Study Guide

American Players Theatre Presents August Wilson’s FENCES 2019 Study Guide American Players Theatre / PO Box 819 / Spring Green, WI 53588 www.americanplayers.org August Wilson’s Fences 2019 Study Guide Penumbra Theatre Company’s 2008 Fences Study Guide by Sarah Bellamy excerpted with permission. APT’s Fences Production Section written by Malek Mayo. Photos by Liz Lauren. Photo of Phoebe Werner by Hannah Jo Anderson. THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR MAKING OUR PROGRAM POSSIBLE Associated Bank * Dennis & Naomi Bahcall * Tom & Renee Boldt * Ronni Jones APT Children’s Fund at the Madison Community Foundation * Rob & Mary Gooze * IKI Manufacturing, Inc. * Kohler Foundation, Inc. * Herzfeld Foundation * THANKS ALSO TO OUR MAJOR EDUCATION SPONSORS This project was also supported in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Players Theatre’s productions of Twelfth Night and Macbeth are part of Shakespeare in American Communities, a program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. This project is supported by Dane Arts with additional funds from the Endres Mfg. Company Foundation, The Evjue Foundation, Inc., charitable arm of The Capital Times, the W. Jerome Frautschi Foundation, and the Pleasant T. Rowland Foundation. 2 Special Thanks to Penumbra Theatre Company Access to Penumbra's full study guide collection can be found at https://penumbratheatre.org/study-guides Penumbra Theatre Company occupies a very unique place within American society, and by extension of that, the world. Penumbra was borne out of the Black Arts Movement, a time charged by civic protest and community action. -

Thesis Slabaugh Ms072117

THE NECESSITY AND FUNCTION OF THE DRAMATURG IN THEATRE A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Melanie J. Slabaugh August, 2017 THE NECESSITY AND FUNCTION OF THE DRAMATURG IN THEATRE Melanie J. Slabaugh Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor School Director James Slowiak J. Thomas Dukes, Ph.D. ______________________________ ______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Durand L. Pope John Green, Ph.D. ______________________________ ______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Hillary Nunn, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….. 5 II. HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF DRAMATURGY ……………………… 3 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and the Hamburg National Theatre ……… 4 Lessing’s Influence on the Dramaturgical Movement …………………. 8 Dramaturgy in American Theatre ……………………………………….. 16 III. PRODUCTION DRAMATURGY ……………………………………………. 13 The Production Dramaturg/Director Relationship ……………………. 15 New Production Dramaturgies …………………………………………… 18 IV. NEW PLAY DEVELOPMENT ………………………………………………… 20 The Role of the Dramaturg in New-Play Development …………..…… 22 The Dramaturg as Supporter ………………………………………..….… 22 The Dramaturg as Guardian ………………………………..………….…. 26 The Dramaturg as Questioner …………………………………..……….. 29 V. DEVISED THEATRE ………………………………………….…………..……. 32 The Tasks of the Dramaturg in Devised Theatre ………………….….… -

Fences Study Guide

Pacific Conservatory Theatre Student Matinee Program Presents August Wilson’s Fences Generously sponsored by Franca Bongi-Lockard Nancy K. Johnson A Study Guide for Educators Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to PCPA at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. 2. Once seated in the theater, students may go to the bathroom in small groups and with the teacher's permission. Please chaperone younger students. Once the show is over, please remain seated until the House Manager dismisses your school. 3. Please remind your students that we do not permit: - food, gum, drinks, smoking, hats, backpacks or large purses - disruptive talking. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Equality Winner’S Name Here | Company Name

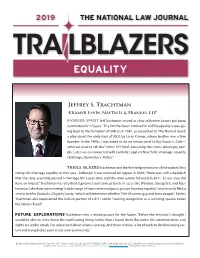

2019 THE NATIONAL LAW JOURNAL EQUALITY WINNER’S NAME HERE | COMPANY NAME Jeffrey S. Trachtman Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP Jeff Trachtman served as chair of Kramer Levin’s pro bono committee for 17 years. “The firm has been involved in LGBTQ equality issues go- ing back to the formation of GMHC, in 1981, as recounted in ‘The Normal Heart,’ a play about the early days of AIDS by Larry Kramer, whose brother was a firm founder. In the 1990s, I was asked to do an amicus brief in Boy Scouts v. Dale— what we used to call the ‘Homo 101’ brief, educating the courts about gay peo- ple. Later, we co-counseled with Lambda Legal on New York’s marriage equality challenge, Hernandez v. Robles.” Trachtman and the firm helped win one of the nation’s first rulings for marriage equality in that case. Although it was reversed on appeal in 2006, “there was such a backlash that the state assembly passed a marriage bill a year later, and the state senate followed in 2011. So our case did have an impact.” Trachtman has also filed Supreme Court amicus briefs in cases like Windsor, Obergefell, and Mas- terpiece Cakeshop representing “a wide range of mainstream religious groups favoring equality” and recently filed a similar brief in Bostock v. Clayton County, “which will determine whether Title VII covers gay and trans people.” Earlier, Trachtman also represented the lesbian partner of a 9/11 victim “seeking recognition as a surviving spouse under the Victims’ Fund.” Trachtman sees a mixed picture for the future. -

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

“Almost Invisible Until Now” Antigone, Ismene, and the Dramaturgy of Tragedy

NORDIC THEATRE STUDIES Vol. 31, No. 1. 2019, 141-154 “almost invisible until now” Antigone, Ismene, and the Dramaturgy of Tragedy KRISTINA HAGSTRÖM-STÅHL ABSTRACT This essay discusses Sophocles’ Antigone in relation to its Hegelian legacy, engaging with the play from a directorial perspective. Drawing on the work of Judith Butler, Anne Carson , Bonnie Honig, Peggy Phelan and Cecilia Sjöholm, I attempt to envision a contemporary mise en scène that repositions feminine subjectivity within the dramaturgy of tragedy. Centering on the relationship between Antigone and Ismene, as well as on the possibility of revaluing Ismene’s position in terms of political and dramaturgical agency, I hope to challenge dramaturgical conventions that assume binary, heteronormative relations as the primary framework of interpretation for female characters, and death and destruction as the only possible outcome for what is positioned as feminine. This resituated reading of the drama examines the function of embodied performance in processes of meaning-making, and offers dramaturgical structure as a site for strategies of resistance. KEYWORDS dramaturgy, tragedy, Hegelian dialectics, feminist theory, performance practice ISSN 2002-3898 © Kristina Hagström-Ståhl and Nordic Theatre Studies PEER REVIEWED ARTICLE Open access: https://tidsskrift.dk/nts/index Published with support from Nordic Board for Periodicals in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NOP-HS) DOI: 10.7146/nts.v31i1.113013 “almost invisible until now” “almost invisible until now” Antigone, Ismene, and the Dramaturgy of Tragedy1 Elle pense qu’elle va mourir, qu’elle est jeune, et qu’elle aussi, elle aurait bien aimé vivre. Mais il n’y a rien à faire. -

Community in August Wilson and Tony Kushner

FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER By Copyright 2007 Richard Noggle Ph.D., University of Kansas 2007 Submitted to the Department of English and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date defended ________________ 2 The Dissertation Committee for Richard Noggle certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER Committee: ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date approved _______________ 3 ABSTRACT My study examines the playwrights August Wilson and Tony Kushner as “political” artists whose work, while positing very different definitions of “community,” offers a similar critique of an American tendency toward a kind of misguided, dangerous individualism that precludes “interconnection.” I begin with a look at how “community” is defined by each author through interviews and personal statements. My approach to the plays which follow is thematic as opposed to chronological. The organization, in fact, mirrors a pattern often found in the plays themselves: I begin with individuals who are cut off from their respective communities, turn to individuals who “reconnect” through encounters with communal history and memory, and conclude by examining various “successful” visions of community and examples of communities in crisis and decay. -

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

A Play and Critical Analysis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository ‘CURRENT REGIMES’ A PLAY & CRITICAL ANALYSIS by LUCY TYLER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MPHIL(B) PLAYWRITING STUDIES Department of Drama and Theatre Arts The University of Birmingham September 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to a number of people without whom this play would not have been the same. Kate North, Steve Waters, Steph Dale, Naomi Cooke and my cohort on the Playwriting course. I would also like to thank my parents. Contents: The Critical Analysis..................................................p.1 Bibliography...............................................................p.30 Appendices.................................................................p.36 Current Regimes- A Play............................................p.52 Fiona and Caroline are stressed. They’re adopting a child together and decide to take a relaxing, last minute holiday to Spain. But there’s a problem. The hotel’s a fascist hotbed, there’s a picture of the Dictator Franco above the twin beds (when they specifically booked a double), and the hotel’s situated right next to Franco’s grave at The Valley of the Fallen.