Can We Keep This "Quiet"?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-18 Olympic Peninsula Travel Planner

Welcome! Photo: John Gussman Photo: Explore Olympic National Park, hiking trails & scenic drives Connect Wildlife, local cuisine, art & native culture Relax Ocean beaches, waterfalls, hot springs & spas Play Kayak, hike, bicycle, fish, surf & beachcomb Learn Interpretive programs & museums Enjoy Local festivals, wine & cider tasting, Twilight BRITISH COLUMBIA VANCOUVER ISLAND BRITISH COLUMBIA IDAHO 5 Discover Olympic Peninsula magic 101 WASHINGTON from lush Olympic rain forests, wild ocean beaches, snow-capped 101 mountains, pristine lakes, salmon-spawning rivers and friendly 90 towns along the way. Explore this magical area and all it has to offer! 5 82 This planner contains highlights of the region. E R PACIFIC OCEAN PACIFIC I V A R U M B I Go to OlympicPeninsula.org to find more O L C OREGON details and to plan your itinerary. 84 1 Table of Contents Welcome .........................................................1 Table of Contents .............................................2 This is Olympic National Park ............................2 Olympic National Park ......................................4 Olympic National Forest ...................................5 Quinault Rain Forest & Kalaloch Beaches ...........6 Forks, La Push & Hoh Rain Forest .......................8 Twilight ..........................................................9 Strait of Juan de Fuca Nat’l Scenic Byway ........ 10 Joyce, Clallam Bay/Sekiu ................................ 10 Neah Bay/Cape Flattery .................................. 11 Port Angeles, Lake Crescent -

Campings Washington Amanda Park - Rain Forest Resort Village - Willaby Campground - Quinault River Inn

Campings Washington Amanda Park - Rain Forest Resort Village - Willaby Campground - Quinault River Inn Anacortes - Pioneer Trails RV Resort - Burlington/Anacortes KOA - Cranberry Lake Campground, Deception Pass SP Anatone - Fields Spring State Park Bridgeport - Bridgeport State Park Arlington - Bridgeport RV Parks - Lake Ki RV Resort Brinnon - Cove RV Park & Country Store Bainbridge Island - Fay Bainbridge Park Campground Burlington Vanaf hier kun je met de ferry naar Seattle - Burlington/Anacortes KOA - Burlington RV Park Battle Ground - Battle Ground Lake State Park Chehalis - Rainbow Falls State Park Bay Center - Bay Center / Willapa Bay KOA Cheney Belfair - Ponderosa Falls RV Resort - Belfair State Park - Peaceful Pines RV Park & Campground - Tahuya Adventure Resort Chelan - Lake Chelan State Park Campground Bellingham - Lakeshore RV Park - Larrabee State Park Campground - Kamei Campground & RV Park - Bellingham RV Park Chinook Black Diamond - RV Park At The Bridge - Lake Sawyer Resort - KM Resorts - Columbia Shores RV Resort - Kansakat-Palmer State Park Clarkston Blaine - Premier RV Resort - Birch Bay State Park - Chief Timothy Park - Beachside RV Park - Hells Canyon Resort - Lighthouse by the Bay RV Resort - Hillview RV Park - Beachcomber RV Park at Birch Bay - Jawbone Flats RV Park - Ball Bayiew RV Park - Riverwalk RV Park Bremerton Colfax - Illahee State Park - Boyer Park & Marina/Snake River KOA Conconully Ephrata - Shady Pines Resort Conconully - Oasis RV Park and Golf Course Copalis Beach Electric City - The Driftwood RV Resort -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

The Totem Line 53 Years of Yachting - 54 Years of Friendship

Volume 55 Issue 3 Our 55th Year March 2010 The Totem Line 53 years of yachting - 54 years of friendship In this issue…Annual awards announced; Membership drive emphasis; Consider WA marine parks Upcoming Events Commodore.………………...….…. Ray Sharpe [email protected] Mar 2…………..…………...…General Meeting Mar 6………... Des Moines Commodore’s Ball Vice Commodore…………… Gene Mossberger Mar 16…………...…………..… Board Meeting [email protected] Mar 17…………….NBC Meeting at Totem YC Mar 18 – 21..….…………Anacortes Boat Show Rear Commodore…….…………….Bill Sheehy Mar 19 – 21.….……………Coming Out Cruise [email protected] Mar 27………....…….………….....Spring Fling C ommodore’s Report The Membership Yearbook is Area Fuel Prices going to print shortly and should http://fineedge.com/fuelsurvey.html be ready for the March general Updated 1/27/10 meeting. Thanks to Gene, Dan and Mary for their efforts. C ommodore (Cont’d) by itself. If there isn’t some one willing to take on I want to thank Gene and Patti the organizing of this event and make it a great end of Mossberger, Bill and Val summer happening, then we need to decide now so Sheehy, and Rocci and Sharon Blair for attending the club can let Fair Harbor know that we’re not The TOA Commodores Ball with Char and myself going to do it. Then they can have it available to other and supporting Totem Yacht Club. boaters that may want it. Last year was a last minute scramble by some dedicated members. It is a lot Val Sheehy has stepped forward to take on the easier if it is done with proper planning. -

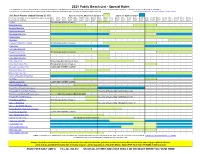

2021 Public Beach List

2021 Public Beach List - Special Rules The following is a list of popular public beaches with special rules because of resource needs and/or restrictions on harvest due to health concerns. If a beach is not listed below or on page 2, it is open for recreational harvest year-round unless closed by emergency rule, pollution or shellfish safety closures. Click for WDFW Public Beach webpages and seasons 2021 Beach Seasons adopted February 26, 2021 Open for Clams, Mussels & Oysters = Open for Oysters Only = For more information, click on beach name below to view Jan1- Jan15- Feb1- Feb15- Mar1- Mar15- Apr1- Apr15- May1- May15- Jun1- Jun15- Jul1- Jul15- Aug1- Aug15- Sep1- Sep15- Oct1- Oct15- Nov1- Nov15- Dec1- Dec15- beach-specific webpage. Jan15 Jan31 Feb15 Feb28 Mar15 Mar31 Apr15 Apr30 May15 May31 Jun15 Jun30 Jul15 Jul31 Aug15 Aug31 Sep15 Sep30 Oct15 Oct31 Nov15 Nov30 Dec15 Dec31 Ala Spit No natural production of oysters Belfair State Park Birch Bay State Park Dash Point State Park Dosewallips State Park Drayton Harbor Duckabush Dungeness Spit/NWR Tidelands No natural production of oysters Eagle Creek Fort Flagler State Park Freeland County Park No natural production of oysters. Frye Cove County Park Hope Island State Park Illahee State Park Limited natural production of clams Indian Island County Park No natural production of oysters Kitsap Memorial State Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Kopachuck State Park Mystery Bay State Park Nahcotta Tidelands (Willapa Bay) North Bay Oak Bay County Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Penrose Point State Park -

New Species and New Records of American Lichenicolous Fungi

DHerzogiaIEDERICH 16: New(2003): species 41–90 and new records of American lichenicolous fungi 41 New species and new records of American lichenicolous fungi Paul DIEDERICH Abstract: DIEDERICH, P. 2003. New species and new records of American lichenicolous fungi. – Herzogia 16: 41–90. A total of 153 species of lichenicolous fungi are reported from America. Five species are described as new: Abrothallus pezizicola (on Cladonia peziziformis, USA), Lichenodiplis dendrographae (on Dendrographa, USA), Muellerella lecanactidis (on Lecanactis, USA), Stigmidium pseudopeltideae (on Peltigera, Europe and USA) and Tremella lethariae (on Letharia vulpina, Canada and USA). Six new combinations are proposed: Carbonea aggregantula (= Lecidea aggregantula), Lichenodiplis fallaciosa (= Laeviomyces fallaciosus), L. lecanoricola (= Laeviomyces lecanoricola), L. opegraphae (= Laeviomyces opegraphae), L. pertusariicola (= Spilomium pertusariicola, Laeviomyces pertusariicola) and Phacopsis fusca (= Phacopsis oxyspora var. fusca). The genus Laeviomyces is considered to be a synonym of Lichenodiplis, and a key to all known species of Lichenodiplis and Minutoexcipula is given. The genus Xenonectriella is regarded as monotypic, and all species except the type are provisionally kept in Pronectria. A study of the apothecial pigments does not support the distinction of Nesolechia and Phacopsis. The following 29 species are new for America: Abrothallus suecicus, Arthonia farinacea, Arthophacopsis parmeliarum, Carbonea supersparsa, Coniambigua phaeographidis, Diplolaeviopsis -

Contact List

WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION State Park Contact Sheet Last Updated June 15, 2021 PARK AREA PHONE PARK NAME ADDRESS REGION EMAIL (@parks.wa.gov) ALTA LAKE STATE PARK Central Lakes Area (509) 923-2473 Alta Lake State Park 1B OTTO ROAD Eastern [email protected] PATEROS WA 98846 FORT WORDEN STATE PARK Anderson Lake Olympic View Area (360) 344-4442 200 BATTERY WAY State Park Southwest [email protected] PORT TOWNSEND, WA 98368-3621 BATTLE GROUND STATE PARK Battle Ground Lake Battle Ground Area (360) 687-4621 18002 NE 249T STREET, State Park Southwest [email protected] BATTLE GROUND, WA 98604 BAY VIEW STATE PARK Salish Foothills (360) 757-0227 Bay View State Park 10901 BAY VIEW – EDISON ROAD Northwest [email protected] MOUNT VERNON, WA 98273-8214 BATTLE GROUND STATE PARK Beacon Rock Battle Ground Area (509) 427-8265 18002 NE 249T STREET, State Park Southwest [email protected] BATTLE GROUND, WA 98604 BELFAIR STATE PARK South Sound Area (360) 275-0668 Belfair State Park P.O. BOX 2787 Southwest [email protected] BELFAIR, WA 98528 Ben Ure DECEPTION PASS STATE PARK Deception Pass Area (360) 675-3767 Island Marine State 41020 STATE ROUTE 20 Northwest [email protected] Park OAK HARBOR, WA 98277 BIRCH BAY STATE PARK Whatcom Bays Area (360) 371-2800 Birch Bay State Park 5105 HELWEG ROAD Northwest [email protected] BLAINE WA 98230 MANCHESTER STATE PARK Blake Island Marine Kitsap Area (360) 731-8330 PO BOX 338 State Park Southwest [email protected] MANCHESTER, WA 98353 MORAN STATE -

Draft Jefferson County, Washington Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) Feasibility Study

Draft Jefferson County, Washington Off-Highway Vehicle (OHV) Feasibility Study 7 February 2007 Active Focus Group – OHV Feasibility Study Dale Brownfield, Just Jeep Junkies 4x4 Club Tim Clouse, Mud Toy 4x4 Club Darrel Erfle, Just Jeep Junkies 4x4 Club Wendy Garcia, Concerned Citizen at Large (Chimacum) Eric Holm, Mud Toy 4x4 Club Mary Holm, Mud Toy 4x4 Club Reuben Lalish, Unaffiliated Dirt Bikes Mike L’Heureux, Mud Toy 4x4 Club David Moore, Mud Toy 4x4 Club Neil Morgan, Just Jeep Junkies 4x4 Club Elton Schweitzer, Unaffiliated 4x4 Davis Steelquist, Concerned Citizen at Large (Quilcene) Jefferson County Frank Gifford, Director, Public Works Department Matt Tyler, Manager, Parks & Recreation Division Warren Steurer, Past Manager, Parks & Recreation Division Consultant Team Tom Beckwith FAICP, Team Leader, Park Planner Bruce Dees ASLA, Landscape Architect, OHV Planner Don Campbell ASLA, Landscape Architect, OHV Planner Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Background 1 1.2 This OHV Feasibility Study 2 1.3 This OHV Feasibility Study objectives 2 1.4 Public involvement 3 1.5 Documentation 4 Chapter 2: IAC and NOVA Funding Programs 2.1 IAC 5 2.2 NOVA program 5 2.3 Eligible ORV projects 7 2.4 Grant assistance limits 8 2.5 Definitions 8 Chapter 3: OHV demand 3.1 NSRE – National Survey of Recreation & the Environment 11 3.2 Washington State IAC household dairy-based surveys 17 3.3 Jefferson County OHV hand/mail-out/mail-back survey 20 3.4 OHV demand in East Jefferson County & OHV Service Area 23 Chapter 4: OHV facilities 4.1 OHV facilities in the -

Recreation Opportunity Guide

RECREATION OPPORTUNITY GUIDE Olympic National Forest http:/www.fs.fed.us/r6/olympic Royal Creek Trail #832 Recommended Season SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER Hood Canal Ranger District – Quilcene Office 295142 Highway 101 S. P.O. Box 280 Quilcene, WA 98376 (360) 765-2200 OPPORTUNITIES: Opportunities for day hiking, fishing, backpacking, horseback riding, ACCESS: The Royal Creek Trail starts 1 mile and viewing scenery. NOTE: Stock not up the Upper Dungeness Trail. Follow US allowed on this trail within the Park. Royal Highway 101 north to Sequim Bay State park. Basin is in the Olympic National Park and is Turn left onto the Louella Road. Go one mile surrounded on three sides by rugged rock ridges. and turn left onto Palo Alto Road. Stay on main Water is available along route. Treat all water road and turn right onto FS #2880. Go past taken from streams before drinking. Pack out Dungeness Forks Campground one mile and stay what you pack in. Please use existing campsites left on FS #2870. Go another 8.7 miles to the when possible and camp at least 100 feet from Upper Dungeness Trail #833. Hike Trail #833 water sources. Practice LEAVE NO TRACE one mile to the beginning of Royal Creek Trail. techniques during your trip. Royal Creek Trail enters Park at 0.5 mile. CLOSURES: Motorized vehicles and mountain FACILITIES: Large parking area. Vault toilet bikes are prohibited. No open campfires allowed near trailhead. above 3,500 feet inside Buckhorn Wilderness. Pets are prohibited in Park. Hwy 101 to Sequim North TOPO MAPS: Buckhorn Wilderness Custom Palo Alto Road No Scale Correct Map or Tyler Peak USGS Quad. -

The Seattle Public Library Werner Lenggenhager Photograph Collection, 1950-1984 Collection Details

The Seattle Public Library 1000 4th Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98104 Werner Lenggenhager Photograph Collection, 1950-1984 CREATOR Werner Lenggenhager EXTENT 35 linear feet, 73 boxes COLLECTION NUMBER: 1000-048 COLLECTION SUMMARY Over 30,000 photographs taken by Werner Lenggenhager depicting Seattle and Washington State. LANGUAGES English PROCESSING ARCHIVIST Jade D’Addario, May 2019 Collection Details Biographical Note Werner Lenggenhager (1899-1988) was a Swiss immigrant, a Boeing employee, and a hobby photographer who made it his life's work to create a photographic record of Seattle's architecture, monuments, and scenery. Over the course of his life, Lenggenhager gave nearly 30,000 prints of his photographs to The Seattle Public Library. His photographs appeared in two books authored by Lucile Saunders McDonald: The Look of Old Time Washington (1971) and Where the Washingtonians Lived: Interesting Homes and the People Who Built and Lived in Them (1972). Collection Description The collection documents scenes throughout Seattle including significant events such as the 1962 World’s Fair and Seafair celebrations, prominent buildings throughout the city, street views, and architectural details. Lenggenhager also traveled extensively throughout Washington State and documented his travels with photographs of historical monuments and memorials. Over 4800 of the photographs in this collection are available online through our digital collections. Arrangement Description Correspondence, indexes and other paperwork are arranged alphabetically by material type at the start of the collection. Photographs are arranged alphabetically in their original order according to the subjects assigned by the photographer. Separated Materials Some of Lenggenhager’s photographs can also be found in our Seattle Historical Photograph Collection and Northwest Photograph Collection. -

2019 Public Beach List

2019 Public Beach List - Special Rules The following is a list of popular public beaches with special rules because of resource needs and/or restrictions on harvest due to health concerns. If a beach is not listed below or on page 2, it is open for recreational harvest year-round unless closed by emergency rule, pollution or shellfish safety closures. Click for WDFW Public Beach webpages and seasons 2019 Beach Seasons Open for Clams, Mussels & Oysters = Open for Oysters Only = For more information, click on beach name below to view Jan1- Jan15- Feb1- Feb15- Mar1- Mar15- Apr1- Apr15- May1- May15- Jun1- Jun15- Jul1- Jul15- Aug1- Aug15- Sep1- Sep15- Oct1- Oct15- Nov1- Nov15- Dec1- Dec15- beach-specific webpage. Jan15 Jan31 Feb15 Feb28 Mar15 Mar31 Apr15 Apr30 May15 May31 Jun15 Jun30 Jul15 Jul31 Aug15 Aug31 Sep15 Sep30 Oct15 Oct31 Nov15 Nov30 Dec15 Dec31 Ala Spit No natural production of oysters Belfair State Park Birch Bay State Park Dosewallips State Park Clam season open August 15 through September 7. Oysters open year-round. Drayton West Duckabush Dungeness Spit/NWR Tidelands No natural production of oysters Eagle Creek Fort Flagler State Park Freeland County Park No natural production of oysters. Frye Cove County Park Hope Island State Park Illahee State Park Limited natural production of clams Indian Island County Park No natural production of oysters Clam & oyster season open August 15 - September 7 Kitsap Memorial State Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Kopachuck State Park Mystery Bay State Park Nahcotta Tidelands (Willapa Bay) North