Case Study Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerca Il Codice Della Barra Oregon (Che Trovi Nel Nostro Titolo) E Premi "Successivo" Sino a Quando Non Arrivi Alla Marca Della Tua Motosega

Con la funzione "Trova" cerca il codice della barra Oregon (che trovi nel nostro titolo) e premi "Successivo" sino a quando non arrivi alla marca della tua motosega. cm “ “ mm SL/MP/SP/GP SX/PXB/SFG/SFH RN AT SD/ML/DG AEG® KES35, 30 12 91 0.050 1,3 91VG/91VX/91P 6 45E 120SPEA041* 120SXEA041 120SDEA041* KS30, KS35, KS40 35 14 52E 140SPEA041* 140SXEA041 140SDEA041* 40 16 57E 160SPEA041* 160SXEA041 160SDEA041* KES36 33 13 .325 0.063 1,6 22BPX/LPX 7 56E 133SLBD025 38 15 62E 153SLGD025 153SFGD025 153RNBD025 40 16 67E 163SLGD025 163SFGD025 163RNBD025 163ATMD025 45 18 74E 183SLGD025 183SFGD025 183RNBD025 183ATMD025 50 20 81E 203SLGD025 203ATMD025 33 13 3/8 0.063 1,6 75LGX/LPX/D/DP 7 52E 38 15 56E 153SLHD025 153SFHD025 153RNDD025 40 16 60E 163SLHD025 163SFHD025 163RNDD025 163ATMD025 45 18 66E 183SLHD025 183SFHD025 183RNDD025 183ATMD025 50 20 72E 203SLHD025 203SFHD025 203RNDD025 203ATMD025 ALKO E1200, 1400E, 1500E, 2000, 2300, 30 12 91 0.050 1,3 91VG/91VX/91P 7 45E 120SPEA041* 120SXEA041 120SDEA041* E125, 25A, KS, KSB, 35 14 52E 140SPEA041* 140SXEA041 140SDEA041* KE4000, KE3500 VARIO 40 16 57E 160SPEA041* 160SXEA041 160SDEA041* KB3500, KB4000, 30 12 91 0.050 1,3 91VG/91VX/91P 6 44E 120SDEA218* KB4500, BKS38-35 35 14 49E 140SPEA218* 140SDEA218* 35 14 50E 40 16 55E 160SPEA218* 160SDEA218* 140 30 12 .325 0.050 1,3 20BPX/LPX 7 55E 35 14 61E 240 35 14 .325 0.050 1,3 20BPX/LPX 7 57E KB5000 40 16 .325 0.050 1,3 20BPX/LPX 7 65E 160SLGZ095 40 16 66E 160SLGK095 160RNBK095 45 18 72E 180SLGK095 1074, P21, P26, P28 35 14 .325 0.058 1,5 21BPX/LPX 7 60E 40 16 -

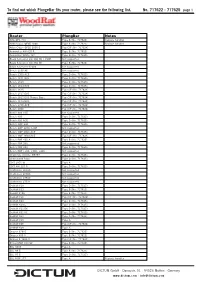

To Find out Which Plungebar Fits Your Router, Please See the Following List

To find out which PlungeBar fits your router, please see the following list. No. 717622 - 717625 page 1 Router PlungBar Notes AEG OFS 710 Type B (No. 717623) Replace handles Atlas Copco OFSE 1000 Type B (No. 717623) Replace handles Atlas Copco OFSE 2000 E Typ C/F (No. 717624) Axminster AW 635 R Type B (No. 717623) Axminster White 127 Type D (No. 717625) Black & Decker KW 800 EK / 780E Not supported Black & Decker KW 850 EK Type B (No. 717623) Black & Decker RP200 Not supported Bosch 1100 AE Not supported Bosch 1300 ACE Type D (No. 717625) Bosch 1611 EVS Type D (No. 717625) Bosch 1613 Type D (No. 717625) Bosch 1614 EVS Type D (No. 717625) Bosch 1615 Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 1617 EVS Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 1617 EVS Plunge Base Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 1619 EVS Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 1700 ACE Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 2000 Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch 600 ACE Not supported Bosch 800 Type D (No. 717625) Bosch 900 ACE Type D (No. 717625) Bosch GOF 900 Type D (No. 717625) Bosch GOF 1250 (L)CE Not supported Bosch GOF 1300 ACE Type D (No. 717625) Bosch GOF 1600 ACE Typ C/F (No. 717624) Bosch POF 400 A Type B (No. 717623) Bosch POF 500 Not supported Bosch POF 800 Type D (No. 717625) Bosch POF 1100, 1300, 1400 Not supported Challenge Xtreme M5757 Type D (No. 717625) Charnwood P220 Type D (No. 717625) CMT 1850 W Type A CMT AW 127 R Type D (No. -

Always the Appropriate Accessories for Your Machine!

... always the appropriate accessories for your machine! Orbital sander sheets STANDARD punched type A punched type B punched Size: Width x length 93 x 230 mm 115 x 280 mm 93 x 230 mm 93 x 230 mm 115 x 280 mm Part.-No. Part.-No. Part.-No. Part.-No. Part.-No. Manufacturer / machine model 815- 812- 8181- 8182- 8187- UNIVERSAL With clamps without dust extraction x x AEG VS 130, VSE 130, VS 230 x x VSS 260/E, VS 230/E x VS 14, VS 20, VSE 20, VSS 20 x VSS 20/E, VS 250, VSE 250 x VSS 280, VSSE 280 x VS 280/E, FS 280 x ALPHA TOOLS ASS 280 x ATLAS COPCO VS 230, VSE 230, x x VSS 260, VSSE 260 x x VS 280 E, VS 280 SE x VSE 230, VSS 20 E x BLACK & DECKER DN 41 A, DN 41 AE, BD 175, BD 180, x x BD 180 E, KA 300, KA 185, KA 185 E x x BD 175, BD 180 E, DN 41 AE, x x DN 180 E, KA 186 E, KA 196, KC 185 E x x KC 273, KC 962, CD 400, VB 135 B x x SR 400, PL 52 BD 273, DN 49, DN 273, x DN 41 AE, DN 180 E, KC 962, x P 63-03, P 63-04, P 63-05, x KA 180 E, KA 274 EKA, x SR 410 E, VB 135 A, VB 250 E x KA 273 x KA 310, KA 320 EKA, KA330 EKA x x BOSCH GSS 23 AE, GSS 230 A/ AE x x PSS 23 A/AE, PSS 240 A/AE x x GSS 23 AE, PSS 230 x x GSS 9,6 V, GSS 140 A GSS 28 A/AE, GSS 280 A/AE, x PSS 28 AE, PSS 280 AE, PSS 300 AE x GSS 28 A x CASALS BLR 170, YLR 210 x x BLR 250 x LN 216, LR 228 x DEWALT DW 411, D26411 D26420, D26421 x D26422, D26423 x x EINHELL TC-OS 1520/1 x EST 170 x x RT-OS 30, TE-OS 2520 x BT-OS 280 E x BT-RS 420 E, RT-XS 28 232 Orbital sander sheets standard Orbital sander sheets STANDARD punched type A punched type B punched Size: Width x length 93 x 230 mm 115 x 280 mm 93 x 230 mm 93 x 230 mm 115 x 280 mm Part.-No. -

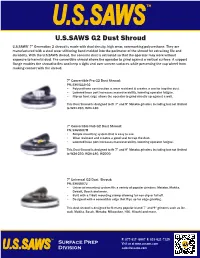

U.S.SAWS G2 Dust Shroud U.S.SAWS’ 7” Generation 2 Shroud Is Made with Dual Density, High Wear, Non-Marking Polyurethane

U.S.SAWS G2 Dust Shroud U.S.SAWS’ 7” Generation 2 shroud is made with dual density, high wear, non-marking polyurethane. They are manufactured with a steel wear stiffening band molded into the perimeter of the shroud for extra-long life and durability. With the U.S.SAWS shroud, the concrete dust is extracted so that the operator may work without exposure to harmful dust. The convertible shroud allows the operator to grind against a vertical surface. A support flange enables the shroud to flex and keep a tight seal over uneven surfaces while preventing the cup wheel from making contact with the shroud. 7” Convertible Pro G2 Dust Shroud: PN: SX60115-G2 • Polyurethane construction is wear resistant & creates a seal to trap the dust. • Lowered hose port increases maneuverability, lowering operator fatigue. • Flip up front edge allows the operator to grind directly up against a wall. This Dust Shroud is designed to fit 7” and 9” Metabo grinders including but not limited to W24-230, W24-180. 7” Convertible Hub G2 Dust Shroud: PN: SX65807M • Simple mounting system that is easy to use. • Wear resistant and creates a good seal to trap the dust. • Lowered hose port increases maneuverability, lowering operator fatigue. This Dust Shroud is designed to fit 7” and 9” Metabo grinders including but not limited to W24-230, W24-180, W2000. 7” Universal G2 Dust Shroud: PN: SX65807U • Universal mounting system fits a variety of popular grinders: Metabo, Makita, Dewalt, Bosch and more. • Built with a T-Bolt mounting clamp allowing for non-slip or fall off. -

2010 Financial Report Web 2.Pdf

Contents Page 2 This is Hilti 3 Our mission statement – and how we live its values 4 Key figures 5 Management report 7 The Board of Directors 10 Other key management personnel 13 Corporate governance 15 Consolidated financial statements of Hilti Group 19 Auditors’ report on the consolidated financial statements 79 Financial statements of Hilti Corporation Ltd 83 Auditors’ report on the financial statements 94 Contact information 95 Next information 95 2010 Financial Report This is Hilti Page 3 This is Hilti We supply the construction industry with technologically superior products, systems and services. We provide innovative solutions that feature outstanding added value. We passionately create enthusiastic customers and build a better future with approximately 20,000 team members located in more than 120 countries around the world. We live clear values. Integrity, the courage to embrace change, teamwork and commitment are the foundations of our corporate culture. We combine long-term financial success with comprehensive responsibility toward society and the environment. Reciprocal tenets of openness, honesty, and tolerance apply to team members, partners and suppliers alike. Our corporate goal is to generate sustainable profitable growth. Our Mission Statement – and how we live its values Page 4 Our mission statement – and how we live its values Mission statement We create enthusiastic customers and build a better future! Enthusiastic customers We create success for our customers by identifying their needs and providing innovative and value-adding solutions. Build a better future We foster a company climate in which every team member is valued and able to grow. We develop win-win relationships with our partners and suppliers. -

ETCO Linecard Web.Pdf

• Stellram SOLID CARBIDE TOOLING CARBIDE TIPPED TOOLS • STS • Aerosharp • Hannibal Carbide Tool • Sumitomo • Bassett • Hilti ET BRAND SOLUTIONS • Tool-Flo • CJT-Koolcarb • Lexington Cutter • ET Carbide Inserts • Toolmex • Classic Carbide • Wetmore Tool & Engineering • ET Round Tools • Vardex/VNE • Cleveland • Vertex • Cougar HIGH SPEED STEEL INDEXABLE TOOLING • Walter USA • Data-Flute • Alvord-Polk • Allied/ACME • Winco • Dormer • Award • Allied Tool Products • Xactform • Dura-Mill • Brubaker • Bison/TMX • Elenco • Chicago-Latrobe • Ceratip/Kyocera BORING TOOLS & SYSTEMS • Emuge • Cleveland • Ceratizit • Big Kaiser • Engman-Taylor • Dormer • Circle Cutting Tools • Circle Precision Cutting Tools • Fullerton • Drillco • Circle Machine • Criterion • HAM • Engman-Taylor • Citco • Komet • Hannibal Carbide Tool • George Whalley • Clapp-Dico • Parlec • Harvey • Greenfield • Competitive Carbide • Sandvik Coromant • Huff • Hayden • Criterion • Steiner Technologies • IMCO • Keo • Crystallume • Walter USA • INOVA Tools • Koncor • Dorian Tool • Wohlhaupter • JEL/Komet • Melin • Elliott/Monaghan • Jewell Tool Technology • Metcut • Engman-Taylor TAPPING & THREADING • Johnson Carbide • Michigan Drill • Everede • Advent • LMT • Monaghan Tooling Group • H.A.M. • Balax • M.A. Ford • Morse Cutting Tools • Heule • Bass USA • Mastercut • National Twist • Horizon Carbide • Besly • Melin • Niagara Cutter • Horn USA • Carmex Precision Tools • Metal Removal • OSG • Indexable Cutter Engr. • Emuge • Metcut • Precision Twist Drill • Indexa-V • Engman-Taylor • Micro -

Stanley Black and Decker Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) Chevron

Who Owns What? Andrew Davis May, 2019 This is a redacted version of an article II found on protoolreviews.com. I remember growing up when General Motors offered different brands at different price points (until they all the brands started to overlap before GM collapsed) – Cadillac at the top end, followed by Oldsmobile, Buick, Pontiac, and Chevy. We have a similar situation in woodworking tools (also in kitchen appliances) except that in the case of tools, the multi-brand company is more often a case of acquisitions rather than organic development. Anyway, for those readers interested in the business side of tools, this column, which is a departure from my usual thread, may be of interest. Stanley Black and Decker Stanley Black & Decker (SBD) turned heads when it bought Craftsman Tools in 2017 after Sears closed 235 stores in 2015. Dating back to 1843 with a man named Frederick Stanley, the company merged in 2010 with Black and Decker. As of 2017, the company maintains a $7.5 billion business in tools & storage alone. SBD brands include: DeWalt Stanley Black + Decker Bostitch Craftsman Vidmar Mac Tools Irwin Lenox Proto Porter-Cable Powers Fasteners Lista Sidchrome Emglo USAG Techtronic Industries Co Ltd (TTI) TTI owns Milwaukee Tool and a host of other power tool companies. It also licenses the RIDGID and RYOBI names for cordless power tools (Emerson actually owns RIDGID and makes the red tools). Founded in 1985 in Hong Kong, TTI sells tools all over the world and employs over 22,000 people. TTI had worldwide annual sales of over US$6 billion in 2017. -

World Power Tools

INDUSTRY MARKET RESEARCH FOR BUSINESS LEADERS, STRATEGISTS, DECISION MAKERS CLICK TO VIEW Table of Contents 2 List of Tables & Charts 3 Study Overview 4 Sample Text, Table & Chart 5 Sample Profile, Table & Forecast 6 Order Form & Corporate Use License 7 About Freedonia, photo: Morse, M. K., Co. Custom Research, Related Studies, 8 World Power Tools Industry Study with Forecasts for 2015 & 2020 Study #2763 | June 2011 | $6100 | 346 pages The Freedonia Group 767 Beta Drive www.freedoniagroup.com Cleveland, OH • 44143-2326 • USA Toll Free US Tel: 800.927.5900 or +1 440.684.9600 Fax: +1 440.646.0484 E-mail: [email protected] Study #2763 June 2011 World Power Tools $6100 346 Pages Industry Study with Forecasts for 2015 & 2020 Table of Contents Switzerland .................................................. 126 Ingersoll-Rand plc ......................................... 305 United Kingdom ............................................ 131 Jiangsu Dongcheng Power Tools ...................... 307 Other Western Europe .................................... 136 Jinding Group............................................... 308 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Kingfisher plc ............................................... 309 ASIA/PACIFIC Kulkarni Power Tools ...................................... 312 MARKET ENVIRONMENT Makita Corporation ........................................ 314 General ....................................................... 143 Metabowerke GmbH ....................................... 317 General ......................................................... -

SDS-Plus Carbide Drill Bits

SDS-Plus Carbide Drill Bits 68.0 SDS-Plus Carbide Drill Bits Cat- flH^HMflP Usable Std. Wt./ No. ^^^^SH^^^ Length Pouch Dozen 68.1 Introduction 0373 27/32" 8 "x 6" 1 8 SDS-Plus Carbide drills are designed for use in a rotary 0375 7/8" x 8" 6" 1 8-1/4 0376 " 7/812 x " 10" 1 9 hammer equipped wit SDn ha S (slotted drive shaft) type 0377 " 7/816 x " 16" 1 15 chuck. The bits meet ANSI standards and can be used to 0379 1"x8" 6" 1 9-1/2 dril concreten i l , block, brick sofd t,an stone. 0380 1"x10" 8" 1 10 0381 1"x12" 10" 1 13 68.2 Product Description 0382 1 " x 18" 16" 1 18 0394 *Splin SDeo t S Adapter SDS-Plus Carbide Drill Bits are manufactured from high 0396 *SDS Max Adapter - grade alloy tool stee carefulla n i l y controlled processo t * Use of SDS-Plus drill bit in larger rotary hammers with an adapter will reduce bit life. insure maximum life. A special flute design incorpo- Special Application Bit for 3/8" Pipe SPIKE For use in hard aggregate concrete. Job site tests required. 0390 7mm x 4" Pipe SPIKE Bit 2" 1 ' SDS-Plus Carbide Drill Bit Bulk Packs rate doublsa e flute wit hreinforcea d cor insuro et e Cat. Usable Drills Wt./ quick, efficient dust removal which reduces wear result- No. Size Length Per Pack Dozen ing in longer bit life. The shank is formed in an SDS-Plus 0664 3/16" X4" 2" 25 1 0666 3/16" 6 x " 4" 25 1 configuration with chamfered positive drive slots to 0668 3/16" 8 x " 6" 25 1-1/4 deliver maximum torqu impacd ean t energ r fasteyfo r 0670 3/16" 10 x " 8" 25 1-1/2 drilling. -

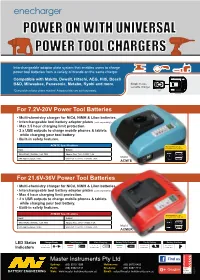

A4 Enecharger ACMTE & ACMGR Flyer 2-Pge V2 Low Colour

POWER ON WITH UNIVERSAL POWER TOOL CHARGERS Interchangeable adaptor plate system that enables users to charge power tool batteries from a variety of brands on the same charger. Compatible with Makita, Dewalt, Hitachi, AEG, Hilti, Bosch B&D, Milwaukee, Panasonic, Metabo, Ryobi and more. Simple to use, versatile charger Interchangeable Adaptor *Compatible adaptor plates required. Adaptor plates are sold separately. Plate Charger Base For 7.2V-20V Power Tool Batteries • Multi-chemistry charger for NiCd, NiMH & LiIon batteries. • Interchangeable tool battery adaptor plates (sold separately). • Max 2.5 hour charging limit protection. • 2 x USB outputs to charge mobile phones & tablets while charging your tool battery. • Built-in safety features. ACMTE Specifications Dual USB Ports: Suitable for smartphones & tablets. Input Output 100-240VAC, 50-60Hz, 1.2A, 70W Adaptor Port: 7.2V - 18VDC 1-3A Model: SAA approved power cable USB Port: 2 x 5VDC 2.1A max. each ACMTE For 21.6V-36V Power Tool Batteries • Multi-chemistry charger for NiCd, NiMH & LiIon batteries. • Interchangeable tool battery adaptor plates (sold separately). • Max 4 hour charging limit protection. • 2 x USB outputs to charge mobile phones & tablets while charging your tool battery. • Built-in safety features. ACMGR Specifications Dual USB Ports: Suitable for smartphones & tablets. Input Output 100-240VAC, 50-60Hz, 1.2A, 70W Adaptor Port: 21.6V - 36VDC 1-2A Model: SAA approved power cable USB Port: 2 x 5VDC 2.0A max. each ACMGR LED Status Indicators https://www.facebook.com/mi.battery.experts -

Circular Saws 530 | Circular Saw Blades | Overview Bosch Accessories for Power Tools 09/10

Circular saws 530 | Circular Saw Blades | Overview Bosch Accessories for Power Tools 09/10 531 The right circular saw blade for 537 Optiline Wood 548 Construct Wood every job 533 More bite thanks to the sharp 542 Speedline Wood 551 Construct Metal teeth from Bosch 535 The right circular saw blade for 545 Multi Material 554 Accessories for Circular Saws any saw The new circular saw blade range: Five outstanding lines for all conventional applications. Bosch has expanded its range of circu- lar saw blades for mitre saws, cordless handheld circular saws and construction site bench circular saws. Bosch now offers circular saw blades specially designed to cut metal. The circular saw blade range now perfectly meets the needs of specialist dealers and professional tradesmen. These fi ve product lines cover every applica- tion, from interior jobs to construction. Tried and tested Bosch quality and outstanding performance guarantees satisfi ed customers. The outstanding value for money increases the demand for Bosch blades and therefore the sales volume. Our colour coding system and clearly labelled packaging means you can fi nd the right blade more quickly and easily than ever before. Bosch Accessories for Power Tools 09/10 Circular Saw Blades | Overview | 531 The right circular saw blade for every job. A precise blade for producing a quality cut in all standard woodworking applications. A fast blade for cuts along and across all types of wood. The perfect blade for making powerful cuts with clean cutting edges in all different kinds of materials. The ideal blade for making coarse cuts through construction site timber. -

Catalogue 45 Circular Saw Blades Made in Germany

3869 RZ EDN Katalog 2009 D_Kapitel1:EDN Katalog 07.04.2009 15:19 Uhr Seite U_1 Catalogue 45 Circular Saw Blades Made in Germany 3869 RZ EDN Katalog 2009 D_Kapitel1:EDN Katalog 07.04.2009 15:19 Uhr Seite U_2 3869 RZ EDN Katalog 2009 D_Kapitel1:EDN Katalog 07.04.2009 15:07 Uhr Seite 1 Carbide tipped saw blades ”Made in Germany” Content More than 45 years a name in the sawing industry! Seite Material allocation / technical information 2-4 Superline saw blades 5-9 LWS · UWS · KWS · VWS · KTS · VTS · KDTH pos. + neg. Standard saw blades 11-18 LFZ · LWZ · LF · QW · UW · GW · KWG · KW · VW ATS (Anti-Sound) saw blades 19-20 Special saw blades 21-44 LWD · UWD · VWD · FWD · NFD · WKN · LWP · VWN · UH · VTH · KDH pos. + neg. KTF · VTF · VWF · RSK · RS · UWP · PTF · ZFR · ZWR · LFR · LW · LFB · WPA · LW Saw blades for tenoner · Groover · Lamello Aluminium and steel saw blades 45-65 NE Pos. · NE neg. · STI · STS · STW · HS DM05 · HSE · segment saw blades tube saws · ATF Series 05 saw blades 66-72 For portable power saws, crosscut saws, mitre saws and saw benches Construction site saw blades 73-77 CV · BWK · BTS · BTK · BHS · BFA Mini-Groover / Portas bits 78-80 Reducing rings 82-83 Reworking and custom-made products 84 1 3869 RZ EDN Katalog 2009 D_Kapitel1:EDN Katalog 07.04.2009 15:07 Uhr Seite 2 Technical details Material allocation Which EDN saw blade for which material? Material Saw types particularly recommended Saw types for good cutting quality Natural wood soft-longitude LFZ2, LF, LW, LFR, ZFR LFZ1, LWS, LWZ, QW, UWS, UW, GW, WPA, ZWR soft-cross