Native Plants of Deer Canyon Preserve One-Seed Juniper: February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aegean Trees and Timbers: Dendrochronological Survey of the Island of Symi

Article Aegean Trees and Timbers: Dendrochronological Survey of the Island of Symi Anastasia Christopoulou 1,* , Barbara Gmi ´nska-Nowak 1, Yasemin Özarslan 2 and Tomasz Wa˙zny 1 1 Centre for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Faculty of Fine Arts, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Toru´n,Poland; [email protected] (B.G.-N.); [email protected] (T.W.) 2 Department of Archaeology and History of Art, Koç University, 34450 Istanbul, Turkey; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: The current study presents the results of the first dendrochronological survey performed over the East Aegean island of Symi. Research Highlights: Dendrochronological research of the East Aegean region is of paramount importance since dendrochronological data from the region, and especially the islands, are still limited. Background and Objectives: The main aim of the study is to explore the dendrochronological potential of the island, focusing on the dating of historical wood and buildings as well as dendroprovenancing. Materials and Methods: A total of 57 wood samples were collected from historical timber from windmills and architectural elements, including doors and warehouse planks, while 68 cores were collected from the three dominant tree species of the island—Cupressus sempervirens, Pinus brutia, and Quercus ithaburensis subsp. macrolepis—in an attempt to develop local reference chronologies that could be useful in dating historical timber Results: Of the historical timber, at least nine different species have been detected, with conifers representing the majority of the collected material. In total, 56% of the dendroarchaeological samples, belonging to four different species, were dated absolutely. -

Pinus Brutia

Priorities on the Utilization of the Results of Ankara-İlyakut Turkish Red Pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) Provenance Trial in Related Semi-Arid Conditions of Central Anatolia a) 26 Turkish red pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) provenance trials were established in a randomized complete block design with three replications in 1988 and 1989 throughout the country. • Turkish red pine (Pinus brutia Ten.) provenance trials are of international based. One sample plot established in Northern Cyprus. a) In İlyakut sample plot 40 km away from Ankara, 36 provenances of Pinus brutia Ten. included in the trial in 1989. c) Periodical observations done each year and collected data analyzed in 1993 (5th year), 1998 (10th year), and 2001 (14th year). d) Growth and survival rates were analyzed. e) New observations made last month. Turning Statistics into Knowledge -I a)It has been shown that; 14-year old experiment has essential clues for reaching conclusions. b)Response to environmental changes are clear among provenances. • All provenances from Cyprus are of non-resistant to frost from the beginning. c) There are cold resistant provenances from different altitudes, latitudes, and longitudes. Turning Statistics into Knowledge -II d) For Pinus brutia the main important variations to be searched for frost resistance, survival, and growth rate respectively. e) There were significant differences among provenances for growth rate, survival, and tolerance… f) All provenances are very tolerant to drought comparing to the Taurus Cedar and Pinus nigra J. F. Arnold subsp. nigra var. caramanica planted in the same locality.g) Turning Statistics into Knowledge -III a) the most adaptable fastest growing, pest and frost resistant provenances are: • 3 (Anamur-Gökçesu-600 m), 5 (Gülnar-Pembecik- 650 m), • 7 (Silifke-Kızlardağı-125 m), 29 (Antakya-Uluçınar-385 m), • 23 (Sındırgı-Bigadiç-350 m), 35 (Siirt-Fındık-700 m), • 4 (Anamur-Yivil-650 m), 27 (Sütçüler-Karadağ-650 m), • 10 (Bucak-Merkez-800 m), 33 (Dursunbey-Delikdere-600 m), • 6 (Tarsus-Karakoyak- 800 m), 24 (M. -

Lebanon Presenation

Qadisha Valley and the Cedars of Lebanon The Cedars of God Arz ar-Rabb “Cedars of the Lord”) is one of the last vestiges of the extensive forestsب رﻻ زرأ :The Cedars of God (Arabic • of the Lebanon Cedar,Cedrus libani , that once thrived across Mount Lebanon in ancient times. • Their timber was exploited by the Phoenicians, Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Romans, and Turks.The wood was prized by Egyptians for ship building;the Ottoman Empire used the cedars in railway construction. Mountains of Lebanon Mountains of Lebanon and Interesting Myths. • The Mountains of Lebanon were once shaded by thick cedar forests and the tree is the symbol of the country. • It was once said that a battle occurred between the demigods and the humans over the beautiful and divine forest of Cedar trees near southern Mesopotamia. • This forest, once protected by the Sumerian God Enlil, was completely bared of its trees when humans entered its grounds 4700 years ago, after winning the battle against the guardians of the forest. • The story also tells that Gilgamesh used cedar wood to build his city. History and Biblical History • The Phoenicians used the Cedars Woods for their merchant fleets. • The Egyptians used cedar resin for the mummification process and the cedar wood for some of “their first hieroglyph bearing rolls of papyrus”. • In the Bible, Solomon procured cedar timber to build the Temple in Jerusalem. • During World War I, British troops used cedar to build railroads. • In 1876, Queen Victoria paid for a high stone wall to protect the cedars of God from browsing by goats • The emperor Hadrian claimed these forests as an imperial domain, and destruction of the cedar forests was temporarily halted. -

RESILIENT CEDARS Centuries of Exploitation Have Decimated Lebanon’S Forests, with Its Famous Cedars the Hardest Hit

EXPLORE RESILIENT CEDARS Centuries of exploitation have decimated Lebanon’s forests, with its famous cedars the hardest hit. However, reforestation efforts are showing promising results. 30 FLASHES / JULY 2018 ENVIRONMENT Although the Lebanon cedar, Cedrus libani, is Thankfully, government bodies, USAID’s Lebanon endemic to mountains around the Eastern Medi- Reforestation Initiative (LRI) and other environ- terranean in Lebanon, Syria and Turkey, it is most mental activists are making progress to reverse that closely associated with the former, as it is the national trend – one seedling at a time. Last month, LRI symbol of Lebanon and the central feature of the championed its tree adoption scheme on World Envi- country’s flag. ronment Day, while in November 2017, more than In Lebanon, like many other parts of the world, 2000 people gathered on the summit of Lebanon’s a combination of ecological, socio-economic and Arz Bcharre Mountain and planted 5000 cedar seed- cultural changes has dramatically increased the vul- lings. Those volunteers came from Bcharre families nerability of ecosystems. These factors, combined and neighbouring communities, scouts and activists, with water shortages, extreme weather events and representatives of civil society, private sector employ- large-scale disturbances have seen Lebanon’s green ees, as well as university and school students from spaces shrink to just 13% of the country. across the country. Lebanon’s cedars have been particularly hard hit. The event, organised by LRI and in close collabora- Centuries of deforestation have seen the tree’s former tion with the Municipality of Bcharre, was attended by range of 500,000 hectares reduced to 2000 hectares Lebanon’s First Lady Nadia Aoun, and was aimed at (0.4% of original estimated forest cover). -

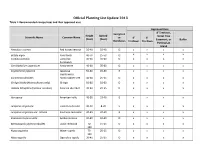

Planting List Update 2013 Table 1: Recommended Canopy Trees and Their Approved Uses

Official Planting List Update 2013 Table 1: Recommended canopy trees and their approved uses Approved Uses 8' Treelawn, Evergreen Height Spread Street Tree Scientific Name Common Name or 4' 6' (Feet) (Feet) Easement, or Buffer Deciduous Treelawn Treelawn Parking Lot Island Aesculus x carnea Red horsechestnut 30-40 30-40 D x x x x Betula nigra River birch 40-70 25-50 D x x x x Carpinus betulus European 40-60 30-40 D x x x x hornbeam Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsuratree 40-60 35-60 D x x x x Cryptomeria japonica Japanese 50-60 20-30 E x x x x cryptomeria Eucommia ulmoides Hardy rubber tree 40-60 25-35 D x x x x Ginkgo biloba (Male cultivars only) Ginkgo 50-80 50-60 D x x x x Halesia tetraptera (Halesia carolina) Carolina silverbell 30-40 20-35 D x x x x Ilex opaca American holly 40-50 18-40 E x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern red cedar 40-50 8-20 E x x x x Juniperus virginiana var. siliciola Southern red cedar 30-45 20-30 E x x x x Koelreuteria paniculata Goldenraintree 30-40 30-40 D x x x x Metasequoia glyptostroboides Dawn redwood 70- 15-25 D x x x x 100 Nyssa aquatica Water tupelo 75- 25-35 D x x x x 100 Nyssa ogeche Ogeechee tupelo 30-45 25-35 D x x x x Nyssa sylvatica Black gum 20-30 D x x x x 30-70 Ostrya carpinifolia Hophornbeam 50-65 25-35 D x x x x Ostrya virginiana American 25-40 20-40 D x x x x hophornbeam Parrotia persica Persian ironwood 20-40 20-35 D x x x x Quercus robur 'fastigiata' Upright English oak 50-60 10-18 D x x x x 40-50 40-50 D x x x x Sapindus drummondii Western soapberry Sassafras albidium Sassafras 30-60 25-40 D x x x x Taxodium ascendens (Taxodium Pondcypress 70-80 15-20 D x x x x distichum var. -

The Cedar Tree Delusion

04‐Nov‐12 The Cedar Tree Delusion Faisal Abu‐Izzeddin Recto Verso November 2012 “Ill fares the land, to hastening ill a prey, Where wealth accumulates, and men decay.” Oliver Goldsmith (1770) 2/ 35 1 04‐Nov‐12 Environmental Situation Today • Cedars are 3% of total forest cover • Stop praising the cedars in public & destroy them in private • Human greed & ignorance going back to Gilgamesh • Cedars proclaimed to be sacred, noble, magnificent • The “cedar tree delusion”: disturbing double standard • Lebanon perfected the art of exaggeration re cedar • Put an end to “dominion” & “cedar tree delusion” 3/ 35 The Landscape • “Elsewhere man has cultivated the land: In the Lebanon, he has made it.” Urquhart • Oldest humanized landscape in the world • Forest and its animals were thought inexhaustible • Men and goats –both greedy – took what they wanted • For centuries no guardians of the public interest in forests and topsoil (Douglas,1951) • “Five thousand years of service to civilization has left the Lebanese highlands a permanently degraded vestige of their former glory.” Eric Ekholm,1976) 4/ 35 2 04‐Nov‐12 The Cedar Tree • Arz Lubnan / Cedar of Lebanon / Cedrus libani • erez (eres) as it appears in the Scripture • (se‐der) is derived from the Arabic kedr meaning worth • “Cedar” also used for other trees • Genus Cedrus, and Species C. libani. • Threatened in Lebanon and restricted in Syria • Plentiful in Turkey 5/ 35 How Many Kinds of Cedars? • Lebanon cedar [Cedrus libani] branches are level • Atlas cedar [Cedrus atlantica] branches ascend -

PROVENANCE TRĐALS in TURKEY Forest Area of Turkey Is 21.18

PROVENANCE TR ĐALS IN TURKEY Forest area of Turkey is 21.18 million hectare, which consists of 26 % of total size of the country. The 44 %, 8.9 million hectare is productive forest and the rest, 56% 11.3 million hectare is unproductive. Unproductive forest area needs to be forested in order to turn into productive forest. However, certain provenances should be used in forestation works. Therefore, which provenance may be used in regional afforestation should be determined, particularly in Turkey, which climatic and soil conditions show great changes from one to another (Simsek et al., 1995). The selection of seed resources is the main factor influencing the productivity of forestation (Urgenc, S., 1982). One of the major objectives of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and its affiliates is to conserve forest tree species and genetic biodiversity. Provenance trials are important particularly at the initial stage of a tree improvement of program. They provide information about the genetic architecture of the species that is utilized for gene conservation programs, and for maximizing gain for a given area (Isık et al., 2002) There are lots of provenance trail in Turkey. The Turkish Forest Research Institutes are carrying out 6 provenances trials. The main aim of these studies is to determine the best performing provenances for forestations, each geographic zone in Turkey. 1-Turkish Red Pine ( Pinus brutia Ten.) Provenance Trial The Turkish Forest Research Institute established it in 1988 on 26 test sites (one of the test side was established in Cyprus). 50 provenances were tested (47 provenances originating from Turkey, 3 provenances from northern Cyprus) below Table 1 . -

And Interspecific Variations of Polycyclism in Young Trees of Cedrus Atlantica (Endl.) Manetti Ex

Intra- and interspecific variations of polycyclism in young trees of Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Manetti ex. Carrière and Cedrus libani A. Rich (Pinaceae) Sylvie Sabatier, Philippe Baradat, Daniel Barthelemy To cite this version: Sylvie Sabatier, Philippe Baradat, Daniel Barthelemy. Intra- and interspecific variations of polycyclism in young trees of Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Manetti ex. Carrière and Cedrus libani A. Rich (Pinaceae). Annals of Forest Science, Springer Nature (since 2011)/EDP Science (until 2010), 2003, 60 (1), pp.19- 29. 10.1051/forest:2002070. hal-00883673 HAL Id: hal-00883673 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00883673 Submitted on 1 Jan 2003 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ann. For. Sci. 60 (2003) 19–29 19 © INRA, EDP Sciences, 2003 DOI: 10.1051/forest: 2002070 Original article Intra- and interspecific variations of polycyclism in young trees of Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Manetti ex. Carrière and Cedrus libani A. Rich (Pinaceae) Sylvie Sabatier*, Philippe Baradat and Daniel Barthelemy Unité Mixte de Recherche, CIRAD-INRA-CNRS-EPHE-Univ. Montpellier II, botAnique et bioinforMatique de l’Architecture des Plantes, TA 40/PSII, 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5, France (Received 15 November 2001; accepted 11 April 2002) Abstract – Growth pattern and polycyclism were studied for three French populations of Cedrus atlantica, and ten populations of Cedrus libani (seven Turkish and three Lebanese populations). -

Approved Plant List (PDF)

Harford County Approved Plant List April 2019 The Harford County Approved Plant list includes: Permitted tree and plant species for afforestation and reforestation, Permitted street tree species, and Permitted tree and plant species for individual landscaping Please note that not all of the plants on this list are native Maryland species, and therefore not all of the plant species on this list can be used to meet mitigation requirements within the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area. Please refer to the Native Plants list from US Fish and Wildlife, on Harford County’s website, for a comprehensive list of appropriate native plant species to use in the Critical Area. Harford County Approved Plant List April 2019 Plant Species Permitted for Afforestation and Reforestation Trees Scientific Name Common Name Acer negundo Boxelder Acer rubrum Red maple Acer saccharum Sugar maple Acer saccharinum Silver Maple Amelanchier canadensis Shadbush serviceberry Betula lenta Black or Sweet Gum Betula nigra River birch Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam Carya cordiformis Bitternut hickory Carya glabra Pignut hickory Carya ovata Shagbark hickory Carya tomentosa Mockernut hickory Catalpa speciosa Northern catalpa Celtis occidentalis Common hackberry Cercis canadensis Eastern redbud Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur hawthorn Crataegus pruinosa Frosted hawthorn Crataegus punctata Dotted hawthorn Diospyros virginiana Common persimmon Fagus grandifolia American beech Hamamelis virginiana Common witchhazel Juglans cinerea Butternut -

The Citrus Route Revealed: from Southeast Asia Into The

HORTSCIENCE 52(6):814–822. 2017. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI11023-16 The Citrus Route Revealed: From Southeast Asia into the Mediterranean Dafna Langgut1 The Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Ancient Environments, The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Israel Additional index words. citrus, Citrus medica, citron, lemon, botanical remains, elite products Abstract. Today, citrus orchards are a major component of the Mediterranean landscape and one of the most important cultivated fruits in the region; however, citrus is not native to the Mediterranean Basin, but originated in Southeast Asia. Here, the route of the spread and diversification of citrus is traced through the use of reliable historical information (ancient texts, art, and artifacts such as wall paintings and coins) and archaeobotanical remains such as fossil pollen grains, charcoals, seeds, and other fruit remains. These botanical remains are evaluated for their reliability (in terms of identification, archaeological context, and dating) and possible interpretations. Citrus medica (citron) was the first citrus to spread west, apparently through Persia and the Southern Levant (remains were found in a Persian royal garden near Jerusalem dated to the fifth and fourth centuries BC) and then to the western Mediterranean (early Roman period, ’third and second centuries BC). In the latter region, seeds and pollen remains of citron were found in gardens owned by the affluent in the Vesuvius area and Rome. The earliest lemon (C. limon) botanical remains were found in the Forum Romanum (Rome) and are dated to the late first century BC/early first century AD. It seems, therefore, that lemon was the second citrus species introduced to the Mediterranean. -

Cedrus Libani A

Güney et al. Botanical Studies (2015) 56:20 DOI 10.1186/s40529-015-0100-z RESEARCH Open Access Cambial activity and xylogenesis in stems of Cedrus libani A. Rich at different altitudes Aylin Güney*, Danielle Kerr, Ayça Sökücü, Reiner Zimmermann and Manfred Küppers Abstract Background: The dynamics of cambial activity and xylogenesis provide information on how and to what extent wood formation respond to climatic variability. The Lebanon Cedar (Cedrus libani A.Rich) is a montane tree species which is distributed along a wide altitudinal range in the northeastern Mediterranean region, currently considered as a potential forest species for Central Europe with respect to climate change. This study provides first data on intra-annual growth dynamics at cellular level using the microcore technique for a montane Mediterranean tree species at different altitudes within and outside its natural range. Results: Microcores were collected fortnightly in the growing season of 2013 in order to study temporal dynamics of cambial activity and xylogenesis in stems of C. libani at different altitudes in the Taurus Mountains (1000 – 2000 m a.s.l.) and at a plantation at Bayreuth (330 m a.s.l.; Germany). The dormant cambium consisted of about 5 cells at the Turkish sites and 7 cells at Bayreuth. Cambial activity set in, when daily minimum temperatures exceeded 0 °C and daily means of air and stem temperature exceeded 5 °C. Xylogenesis started between April and May, ended approximately the end of September to the beginning of October and lasted 134 (at tree line) to 174 days (at the lowest Turkish site). -

Cedrus Libani Cedar-Of-Lebanon1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-136 November 1993 Cedrus libani Cedar-of-Lebanon1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION This is a large stately evergreen, with a massive trunk when mature, and wide-sweeping, sometimes upright branches (more often horizontal) which originate on the lower trunk (Fig. 1). Allow plenty of space for proper development. Dark green needles and cones, which are held upright above the foliage, add to the impressive appearance. Young specimens retain a pyramidal shape but the tree takes on a more open form with age. Like most true cedars, it does not like to be transplanted, and prefers a pollution-free, sunny environment. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Cedrus libani Pronunciation: SEE-drus LIB-an-eye Common name(s): Cedar-of-Lebanon Family: Pinaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5B through 10A (Fig. 2) Origin: not native to North America Uses: wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or for median strip Figure 1. Middle-aged Cedar-of-Lebanon. plantings in the highway; specimen; residential street tree Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out Crown density: open of the region to find the tree Growth rate: slow Texture: medium DESCRIPTION Height: 40 to 50 feet Spread: 20 to 30 feet Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Crown shape: pyramidal 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-136, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: November 1993. 2. Edward F. Gilman, associate professor, Environmental Horticulture Department; Dennis G.