The Last Chapter of the Indian Legion1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence | Freepress Journal

25/04/2016 The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence | Freepress Journal HOME EDIT INDIA CITIES WORLD BUSINESS ENTERTAINMENT SPORTS FEATURES FOOD TRAVEL HEALTH FPJ INITIATIVES PR EPAPER TRENDING NOW #LatestNews #Delhi-Odd-Even #IPL2016 #PanamaLeaks aj a y @ .c o | HOME / BOOK REVIEWS / CMCM / LATEST NEWS / WEEKEND / THE BOSE BROTHERS AND INDIAN INDEPENDENCE The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence — By T R RAMACHANDRAN | Apr 16, 2016 03:03 pm With access to diaries, notes, photographs and private correspondence, this book, written by a member of the Bose family, brings to light previously unpublished material on Netaji and Sarat Chandra Bose. The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence: An Insi der’s Account Madhuri Bose Publisher: Sage Publications Pages: 265; Price: Rs 750 The Bose Brothers and Indian Independence: An Insider’s Account – by Madhuri Bose, the grand-daughter of Sarat Bose and grand niece of Subhas Bose, provides some fresh insight about this country’s freedom movement in particular the role of the formidable Bose brothers. It is the extraordinary brothers who gave up their joys, comforts and lives for the freedom and unity of India. It sheds light on the earnest e‴㐸orts of Sarat, elder brother of Subhas, to preserve a single Bengal in the subcontinent’s east, even if partition in the west was unavoidable. The clandestine network of Subhas in Kolkata included friends who were able to smuggle for his inspection an entire dossier of les that the British-run police kept on him. For an entire week in the summer of 1949 Subhas and his nephew Amiya Nath poured over the les secretly brought to their Elgin Road residence from the intelligence headquarters and returned discreetly to their shelves at dawn. -

His Attitude Towards Netaji and Indian National Army Dr

Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669 Mahatma Gandhi - His Attitude Towards Netaji and Indian National Army Dr. Shridhar Charan Sahoo Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was one of the armed assistance in Germany and South East foremost leaders of the Indian Freedom Asia. Even, He had no hesitation to seek help movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. But in from fascist powers like Germany and Italy course of time, he lost his faith that only who during the time were fighting the British. through the Gandhian As it were “Under the Strategy of non- soul-stirring leadership Violence, India could of Netaji Subhas achieve its freedom Chandra Bose, the from British rule. Indian National Army Unlike other popular launched a frontal leaders of the attack as an integrated movement, he force smashing all dreamt of the barriers of religion, freedom of the caste and creed”. country by waging a What was the war against the precise attitude of the British. During the Mahatma towards Second World War, Netaji and his Indian he made a daring and National Army which thrilling escape from took a different path the country eluding from his strategy of British Intelligence non- Violence? This and formed an Indian divergence in strategy and means and, National Army outside the country to fight methods of struggle in the context of India’s for India’s Freedom. In fact, for his sole life struggle for freedom has led sometimes to a mission to free India from British bondage, dichotomous presentation and perception he left no stone unturned in his quest for of Gandhi –Subhas relationship as if they OCTOBER - 2019 56 Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669 were two parallel lines without any meeting went through but he, in his life, verified the point. -

The Effective Role of Subhash Chander Bose in the Era of II Nd World War Ekta P.G

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://pen2print.org/index.php/ijr/ Volume 05 Issue 21 October 2018 The Effective Role of Subhash Chander Bose in the Era of II nd world War Ekta P.G. Student, Deptt. of History Govt. P G College for Women Rohtak (HR.) Abstract: Indeed, the emergence and development of political maturity. In 1939, when he defeated radical nationalist ideology has its own Gandhi-backed candidate, Patwasi significance in the national movement of Sitaramiah, the then Gandhian leader, who India. During World War II, nationalists like was against him and along with this reason Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose were and many other tiny issues eventually he disappointed by the decision of India's army resigned from the Congress presidency and to fight in favour of the British Government announced the formation of the Forward and they strongly criticized the British Block on May 3, 1939. Then, thereafter in government's decision. In the changing the year of 1942, he founded the Azad Hind times of the then India, Bose visited many Fauj on foreign soil and till the end, he countries of Europe and met nationalist fought for freedom of India. In the current leaders there. For this reason, Subhash research paper the researcher presented, the Chandra Bose remained separate from contribution of Subhash Chandra Bose India's active politics from 1933 to 1938. struggle in regards to India's independence When on January 18, 1938, General struggle. Secretary of Congress, Acharya J.B. Keywords: Subhash Chander Bose, Kripalani announced that Subhash Chandra Independence, Azad Hind Fauj, Congress Bose has been elected as the President of the Party, British Government. -

Azad Hind Fauj : a Saga of Netaji

Orissa Review * August - 2008 Azad Hind Fauj : A Saga of Netaji Prof. Jagannath Mohanty "I have said that today is the proudest day of my Rash Behari Bose on July 4, the previous day. life. For an enslaved people, there can be no The speech he delivered that day was in fact one greater pride, no higher honour, than to be the of his greatest speeches which overwhelmed the first soldier in the army of liberation. But this entire contingents of Indian National Army (INA) honour carries with it a corresponding gathered there under the scorching tropical sun responsibility and I am deeply conscious of it. I of Singapore. There was a rally of 13,000 man assure you that I shall be with you in darkness drawn from the people of South-East Asian and in sunshine, in sorrows and countries. Then Netaji toured in joy, in suffering and in victory. in Thailand, Malay, Burma, For the present, I can offer you Indo-China and some other nothing except hunger, thirst, countries and inspired the privation, forced marches and civilians to join the army and deaths. But if you follow me in mobilised public opinion for life and in death - as I am recruitment of soldiers, confident you will - I shall lead augmenting resources and you to victory and freedom. It establishing new branches of does not matter who among us INA. He promised the poeple will live to see India free. It is that he would open the second enough that India shall be free war of Independence and set and that we shall give our all to up a provisional Government of make her free. -

Bose's Revolution: How Axis-Sponsored Propaganda

University of Massachusetts nU dergraduate History Journal Volume 3 Article 2 2019 BOSE’S REVOLUTION: HOW AXIS- SPONSORED PROPAGANDA INFLAMED NATIONALISM IN WARTIME INDIA Michael Connors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umuhj Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Connors, Michael (2019) "BOSE’S REVOLUTION: HOW AXIS-SPONSORED PROPAGANDA INFLAMED NATIONALISM IN WARTIME INDIA," University of Massachusetts nU dergraduate History Journal: Vol. 3 , Article 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/4anm-5m12 Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umuhj/vol3/iss1/2 This Primary Source-Based Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts ndeU rgraduate History Journal by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 2019 UNDERGRADUATEConnors: BOSE’S HISTORY REVOLUTION JOURNAL 31 BOSE’S REVOLUTION: HOW AXIS-SPONSORED BOSE’SPROPAGANDA REVOLUTION: INFLAMED NATIONALISMHOW AXIS-SPONSORED IN WARTIME INDIA PROPAGANDA INFLAMED NATIONALISMMICHAEL IN C WARTIMEONNORS INDIA MICHAEL CONNORS Published by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst, 2019 31 SUMMER 2019 UniversityUNDERGRADUATE of Massachusetts Undergraduate HISTORY History Journal, JOURNAL Vol. 3 [2019], Art. 2 32 ABSTRACT After decades of subjugation under the British crown, India’s leaders at the onset of the Second World War were split on how to handle nationalist sentiment in their country. Part of the Indian National Congress, an independence-focused political party, these leaders were highly aware of the reality where many common Indian citizens would shed blood for a king that would not validate India as an independent state. -

76Th Anniversary of Azad Hind Government

76th Anniversary of Azad Hind Government drishtiias.com/printpdf/76th-anniversary-of-azad-hind-government The 76th anniversary of the formation of the Azad Hind Government will be celebrated on 21st October, 2019, at the Red Fort, Delhi. Last year on 21st October 2018, the Prime Minister of India hoisted the National Flag at the Red Fort and also unveiled the plaque commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the formation of Azad Hind Government. Azad Hind Government On 21st October 1943, Subhash Chandra Bose announced the formation of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (Free India) in Singapore, with himself as the Head of State, Prime Minister and Minister of War. 1/2 The Provisional Government not only enabled Bose to negotiate with the Japanese on an equal footing but also facilitated the mobilisation of Indians in East Asia to join and support the Indian National Army (INA). The struggle for independence was carried on by Subhash Chandra Bose from abroad. He found the outbreak of the Second World War to be a convenient opportunity to strike a blow for the freedom of India. Bose had been put under house arrest in 1940 but he managed to escape to Berlin on March 28, 1941. The Indian community there acclaimed him as the leader (Netaji). He was greeted with ‘Jai Hind’ (Salute to the motherland). In 1942, the Indian Independence League was formed and a decision was taken to form the Indian National Army (INA) for the liberation of India. On an invitation from Ras Bihari Bose, Subhash Chandra Bose came to East Asia on June 13, 1943. -

Indian Politicalintelligence (IPI) Files, 1912-1950

Finding Aid Indian PoliticalIntelligence (IPI) Files, 1912-1950 Published by IDC Publishers, 2000 • Descriptive Summary Creator: India Office Library and Records. Title: Indian Political Intelligence(IPI) Files Dates (inclusive): 1912-1950 Dates (bulk): 1920-1947 Abstract: Previouslyunavailable material on the monitoring of organisations and individualsconsidered to be a threat to British India. Languages: Language ofmaterials: English, with a few items inUrdu and Hindi. Extent: 624 microfiches; 767 files on 57,811 pages. Ordernumber: IPI-1 - IPI-17 • Location of Originals Filmed from the originals held by: British Library, Oriental & IndiaOffice Collections (OIOC). • History note Indian Political Intelligence was a secret organisation within the IndiaOffice in London, charged with keeping watch on the activities of Indiansubversives (communists, terrorists and nationalists) operating outside India.It reported to the Secretary of State for India through the India Office'sPublic & Judicial Department, and to the Government of India through theIntelligence Bureau of the Home Department. It worked in close collaborationwith the British Government's Security Service (MI.5) and Secret IntelligenceService (MI.6). • Scope and Content The files contain a mass of previouslyunavailable material on the monitoring of organisations and individualsconsidered to be a threat to British India. They include surveillance reportsand intercepts from MI.6, MI.5 and Special Branch, and a large number ofintelligence summaries and position papers. The main thrust -

Rash Behari Bose

Rash Behari Bose February 20, 2021 In news : 66th death anniversary of Rash Behari Bose was observed on 21st January 2021 A brief note his life history He was an Indian revolutionary leader against the British Raj Birth: He was born in 1886, in Subaldaha, Bardhaman district of West Bengal on 25 May 1886 Bose wanted to join the Army but was rejected by the British. He subsequently joined government service as a clerk before embarking on a journey as a freedom fighter Bose married Toshiko Soma of the Soma family, who gave him shelter during his hiding days in Japan He worked in their Nakamuraya bakery to create the Indian curry. The curry is popularly known as Nakamuraya curry. Bose, who was eventually granted Japanese citizenship, passed away on 21 January 1945 at the age of 58 in Japan The Japanese Government honoured him with the Order of the Rising Sun (2nd grade). His role in India’s freedom struggle Early activities He was interested in revolutionary activities from early on in his life, he left Bengal to shun the Alipore bomb case trials of (1908). At Dehradun he worked as a head clerk at the Forest Research Institute. There, through Amarendra Chatterjee of the Jugantar led by Jatin Mukherjee (Bagha Jatin), he secretly got involved with the revolutionaries of Bengal and he came across eminent revolutionary members of the Arya Samaj in the United Provinces (currently Uttar Pradesh) and the Punjab Delhi Conspiracy Case-1912: Bose played a key role in the Delhi Conspiracy Case (attempted assassination on the British Viceroy, Lord Hardinge), the Banaras Conspiracy Case and the Ghadr Conspiracy at Lahore Bomb thrown at Lord Hardinge: On December 23, 1912 a bomb was thrown at Lord Hardinge during a ceremonial procession of transferring the capital from Calcutta to New Delhi. -

Paper Teplate

Volume-03 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-12 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary December -2018 www.rrjournals.com [UGC Listed Journal] Mobilization of Indians for Total War of Independence in South-East Asia Dr. Harkirat Singh Associate Professor, Head, Department of History, Public College, Samana, Punjab (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History The formation of Indian National Army in South East Asia was milestone in Indian freedom Published Online: 10 December 2018 struggle. Subhas Chandra Bose organized the Indian National Army and established the Provisional Government of Azad Hind to mobilize the Indians for the cause i.e. freedom. It Keywords was to be a mass movement of the three million Indians in East Asia, a movement in which Chalo-Delhi, Hindustani, Jai-Hind, every man, woman and child contributed their utmost. The entire movement was to be Azad Hind Fauz. financed and supported by Indians in East Asia. With the mobilized sources S.C. Bose led * the war of liberation against the British at Indo-Burma front. Corresponding Author Email: 73sidhu[at]gmail.com 1. Introduction mobilize all the resources of the Indian people and to lead the The Indian independence movement in South East Asia is fight against the British.” a fascinating and soul-stirring chapter in the history of Indian freedom struggle, which created deep interest and desire in the After S.C. Bose had reorganized the INA and established minds of the Indians to know more and more about it. The the Provisional Government of Azad Hind, he had started purpose of the study is to explore the historical dimensions of working for a Total Mobilization for a Total War with great the Indians who moved to South East Asia, stressing on the vitality, working day and night and knowing no rest or sleep as need to study their contribution to the Indian freedom he was preparing for the last struggle with a view to ensuring movement from outside the country. -

Netaji Bose, Nehru and Anti-Colonial Struggle

10 JANATA, November 11, 2018 Netaji Bose, Nehru and Anti-Colonial Struggle Ram Puniyani India’s anti-colonial struggle has his initiative. Patel regarded Nehru his religious path, but not link it to been the major phenomenon which both as his younger brother and his political and other public issues. built modern India into a secular leader. Some time ago, Modi tried to Throughout his career, he reached democracy. Many political streams propagate that Nehru ignored Sardar out to Muslim leaders, first of all were part of this movement, and all Patel and did not attend his funeral in in his home province of Bengal, to of them struggled in their own way Bombay. Moraji Desai’s biography make common cause in the name of to drive away the British. There were refutes this claim too. He says that India. His ideal, as indeed the ideal also some political streams, the ones Nehru did attend the funeral; this of the Indian National Congress, who upheld a narrow nationalism in was also reported in the newspapers was that all Indians, regardless of the name of religion, who were not a of that time. region, religious affiliation, or caste part of this movement; today, in order As far as Netaji Bose is join together to make common cause to gain electoral legitimacy, either concerned, Nehru and Bose were against foreign rulers.” they are making false claims about close ideological colleagues. The major difference between their being a part of it, or are trying Both were socialists and part of Gandhi–Nehru on one side and Bose to distort events to denigrate the the left wing of the Congress. -

Encounters with Fascism and National Socialism in Non-European Regions

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 2/2012, S. 350-374 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-286-1 Encounters with Fascism and National Socialism in non-European Regions MARIA FRAMKE [email protected] Sugata Bose, His Majesty’s Opponent. Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011, 388 pages, ISBN 9780674047549, Price 29,99€. Ulrike Freitag and Israel Gershoni, eds. 2011. Arab Encounters with Fascist Propaganda 1933-1945. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 37 (3), pp. 310-450, ISSN 0340-613X, Price 20.45€. Israel Gershoni and Götz Nordbruch, Sympathie und Schrecken. Begeg- nungen mit Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus in Ägypten, 1922-1937. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 2011, 320 pages, ISBN 9783879977109, Price 32.00€. Mario Prayer, 2010. Creative India and the World. Bengali Interna- tionalism and Italy in the Interwar Period. In: S. Bose & K. Manjapra, 350 eds. Cosmopolitan Thought Zones. South Asia and the Global Circu- lation of Ideas. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 236-259, ISBN 9780230243378, Price 74.00€. Benjamin Zachariah, 2010. Rethinking (the Absence of) Fascism in In- dia, c. 1922-45. In: S. Bose & K. Manjapra, eds. Cosmopolitan Thought Zones. South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 178-209, ISBN 9780230243378, Price 74.00€. 1. “In India there are no fascists”, claimed Jawaharlal Nehru1 in an inter- view with the correspondent of the Rudé Právo, the daily of the Com- munist Czech Party in July 1938. He went on explaining: REVIEW ESSAY/FORSCHUNGSBERICHT Among the hundreds of millions of Indians there is hardly a per- son who would sympathise with the parties of the totalitarian powers. -

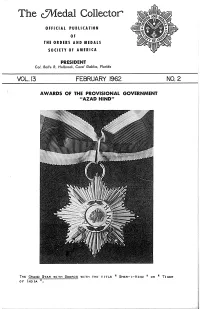

The C Edal Collector'

The c edal Collector’ OFFICIAL PUBLICATIOEI OF THE ORDERS AND MEDALS SOCIETY OF AMERICA PRESIDENT Col. RolIe R. Holbrook, Coral Gables, Florida VOL. 13 FEBRUARY 1962 NO. 2 AWARDS OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT "AZAD HIND" THE GRAND STAR WITH 8WORDS WITH THE TITLE II SHER-I-HIND II OR It TIGER OF INDIA II AWARDS e:: THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT "AZAD HIND== 1= COUNTRY -- PRovISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF FREE INDIA ("AZAD HINDfl) ~e NA~E - ORDERS AND MEDALS OF AZAD HIND FOUNDED BY SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSE ~o WHERE ’ GERMANY ~.~i HISTORY OF COUNTRY -- SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSEt A LONG--TIME RADICAL AGI- TATOR FOR INDIAN INDEPENDENCE= DURING WORLD WAR 11 MADE HIS WAY ILL- EGALLY AND AT GREAT PERSONAL RISK TO GERMANY AND THEN TO ~APANESE - OCCUPIED SOUTH--EAST ASIA, HE WAS ASSISTED BY THE GERMANS AND ~APANESE IN FORMING THE EXILE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF FREE INDIAm WHICH ON 24 OCT, 1943 DECLARED WAR ON GREAT BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES, IN BOTH EUROPE AND ASIA= BOSE ORGANIZED MILITARY FORCES FROM BRITISH -- INDIAN PRISONERS OF WAR AND LOCAL DISSIDENT ELEMENTS, IN ASIA HIS FORCESI NUMBERING 50t000~ FOUGHT FOR THE ~APANESE IN INDO--BURMA~ ON THE PLAINS OF IMPHAL AND IN THE JUNGLES OF ARAKAN= I N GERMANY THE INDIAN LEGION WAS IN THE SERVICE OF THE GERMAN ARMY AND WAS LATER IN- CORPORATED INTO THE 8S-TRooPs= BOSE DIED 1~ AuGusT 1945 IN A PLANE CRASH ON FORMOSA1 WHILE ATTEMPTING TO FLEE TO RUSSIA TO ESOAPE PROSE-- GUTION AS A WAR CRIMINALo 7= PURPOSE - ACCORDING TO THEREGULATIONSp =tin THE HOLY WAS FOR FREE INDIA AND IN FINAL DESTRUCTION OF THE ENGLISH REIGN IN