Vijay Govindarajan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation at Work, by Thinkers50

INNOVATION@WORK WHAT IT TAKES TO SUCCEED WITH INNOVATION www.thinkers50.com INNOVATION@WORK What it takes to succeed with innovation www.thinkers50.com [email protected] Thinkers50 Limited The Studio, Highfield Lane Wargrave RG10 8PZ United Kingdom First published in Great Britain 2018 Copyright © Thinkers50 Limited 2018 Design by www.jebensdesign.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers. ISBN: PDF Edition 9781999873431 ePub Edition 9781999873448 Kindle Edition 9781999873455 Innovation@Work: What it takes to succeed with innovation CONTENTS 5 Foreword Ikujiro Nonaka 7 Introduction Stuart Crainer & Des Dearlove 10 Five keys to innovation Jeanne M. Liedtka & Randy Salzman 14 Codifying innovation Stuart Crainer & Des Dearlove 18 Conquering uncertainty with dual transformation Scott Anthony 22 How companies strangle innovation – and how you can get it right Steve Blank 29 Failure Inc. Gabriella Cacciotti & James Hayton 36 Down-to-earth innovation Stuart Crainer & Des Dearlove 42 On undersolving and oversolving problems Alf Rehn 48 Innovating to make the world a better place Deepa Prahalad 52 Beyond the sticky note: -

Big Small ASKC August Invitation

BIG THINKERS/small dinners Monday, August 26, 2013 6:00 p.m. Peacock Suite, 36th Floor, Lotte Hotel Seoul Unique and private dinners created by Asia Society to foster communication on topics relating to Asia and the United States. Each dinner features a special guest around whom interesting conversation and thought can flow. All dinners will have limited seating to ensure that everyone has a chance to participate actively in the evening’s discussions. The special guest can come from a variety of fields: politics, business, arts or popular culture. These very special evenings are designed to generate new ideas and to provide broader appreciation and understanding of opportunities in Asia. Please RSVP by Monday, August 19, 2013 [email protected] Dinner with Dr. Vijay Govindarajan Dr. Vijay Govindarajan is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading experts Monday on strategy and innovation. He is the Earl C. Daum 1924 Professor of Interna- August 26 tional Business at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. He was the first Professor in Residence and Chief Innovation Consultant at General Electric. 2013 He worked with GE’s CEO Jeff Immelt to write “How GE is Disrupting Itself,” the Harvard Business Review (HBR) article that pioneered the concept of reverse innovation – any innovation that is adopted first in the developing world. HBR rated reverse innovation as one of the ten big ideas of the decade. He has been ranked #3 on the Thinkers 50 list of the world’s most influential business thinkers. Seating is limited. Dr. Govindarajan has worked with CEOs and top management teams in more Reserve now! than 25% of the Fortune 500 firms to discuss, challenge, and escalate their thinking about strategy. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Linking Thoughtful Practice with Insightful Scholarship MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT JAVIER GIMENO Dear SMS members, SMS PRESIDENT It is my pleasure to present the 2019 Annual Report of the Strategic Management Society. The accomplishments presented in this report are the result of the efforts of hundreds of volunteer members and their close collaboration with our SMS staff. I want to thank them all for their commitment and congratulate them on their contributions to our Society. 2019 was a good year for us, as we continue to execute a strategy aligned with our vision of impact, actively shaping the understanding and practice of strategic management while supporting our members’ careers. Our membership stands at around 3,000 members, and we have achieved continued success around our journals, conferences, and research funding. Our financial result was positive, helped by the strong performance of our investment portfolio. I am particularly proud of three accomplishments this past year: 2019 saw a great deal of engagement from our members. We have worked with all the Interest Groups and Communities (IG&Cs) to have a membership engagement officer and have held several sessions focused on membership inclusivity initiatives around gender and practitioner members. We also appointed our first Ombudsperson of the Society, Dana TABLE OF CONTENTS Minbaeva of the Copenhagen Business School. 2019 also saw a focus on identifying activities to promote valuable interactions between academics, business practitioners, and consultants 2 Message from the President (the ABCs of the Society), a goal aligned with survey responses from our members. We are planning several conferences that will have a strong 3 About SMS ABC component, including Berkeley and Hangzhou in 2020 and Milan in 2021. -

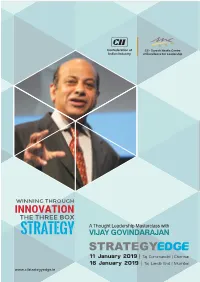

INNOVATION the THREE BOX a Thought Leadership Masterclass with STRATEGY VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN

WINNING THROUGH INNOVATION THE THREE BOX A Thought Leadership Masterclass with STRATEGY VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN 11 January 2019 | Taj Coromandel | Chennai 16 January 2019 | Taj Lands End | Mumbai www.ciistrategyedge.in Govindarajan introduced the Three-Box Solution to GE a few years ago when he was our professor in residence at Crotonville. We embraced it immediately because we saw in it a path to strategic fitness and innovation that was simple, powerful and purposeful Jeffrey R. Immelt Chairman and CEO General Electric Company Dr. Vijay Govindarajan Vijay Govindarajan (VG) is widely regarded as one of the The recipient of numerous awards for excellence in worlds leading experts on strategy and innovation. VG, research, Govindarajan was inducted into the Academy a New York Times and Wall Street Journal Best Selling of Management Journals Hall of Fame, and ranked by Author, is Coxe Distinguished Professor at Dartmouth Management International Review as one of the Top 20 College's Tuck School of Business and Marvin Bower North American Superstars for research in strategy. One Fellow at Harvard Business School. The Coxe Distinguished of his papers was recognized as one of the ten most- Professorship is a new Dartmouth-wide faculty chair. He often cited articles in the entire 40-year history of Academy was the first Professor in Residence and Chief Innovation of Management Journal. Consultant at General Electric. He worked with GEs CEO VG is a rare faculty who has published more than ten Jeff Immelt to write How GE is Disrupting Itself, the articles in the top academic journals (Academy of Harvard Business Review (HBR) article that pioneered Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, the concept of reverse innovation any innovation that Strategic Management Journal) and more than ten articles is adopted first in the developing world. -

VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN Thought Leader on Strategy and Innovation

VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN Thought Leader on Strategy and Innovation Vijay Govindarajan, yang dikenal sebagai VG, secara luas dianggap sebagai salah satu pakar strategi dan inovasi terkemuka di dunia. Dia adalah Earl C. Daum 1924 Profesor Bisnis Internasional di Tuck School of Business di Dartmouth College. Dia adalah Profesor pertama di Residence dan Kepala Inovasi Konsultan di General Electric. Dia bekerja dengan CEO GE Jeff Immelt untuk menulis "Bagaimana GE Mengganggu Diri Sendiri", artikel Harvard Business Review (HBR) yang memelopori konsep inovasi terbalik - inovasi apa pun yang diadopsi pertama kali di negara berkembang. HBR memilih inovasi terbalik sebagai salah satu Momen Hebat dalam Manajemen di Abad Terakhir. Dalam peringkat global terbaru para Topics pemikir manajemen, Govindarajan berada di tempat ketiga. Dinamakan "Rising Super Star" oleh The Economist, VG menulis tentang inovasi Creativity dan eksekusi di blog-nya, Harvard Business Review, dan Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Globalisation Dia adalah co-leader dari inisiatif global untuk merancang House senilai $ 300. Innovation Sebelum bergabung dengan fakultas di Tuck, VG berada di fakultas Harvard Management Business School, INSEAD (Fontainebleau) dan Institut Manajemen India Strategy (Ahmedabad, India). Penerima berbagai penghargaan untuk keunggulan dalam penelitian, Vijay dilantik ke dalam Hall of Fame Jurnal Akademi Manajemen, dan peringkat oleh Management International Review sebagai salah satu dari 20 Top Superstar Amerika Utara untuk penelitian dalam strategi dan organisasi. Salah satu makalahnya diakui sebagai salah satu dari sepuluh artikel yang paling sering dikutip dalam 40 tahun sejarah Academy of Management Journal. VG adalah fakultas langka yang telah menerbitkan lebih dari sepuluh artikel di jurnal akademik teratas (Akademi Jurnal Manajemen, Akademi Tinjauan Manajemen, Jurnal Manajemen Strategis) dan lebih dari sepuluh artikel di jurnal praktisi bergengsi termasuk beberapa artikel HBR terlaris. -

Vijay Govindarajan

VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN Vijay Govindarajan, known as VG, is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on strategy and innovation. Most recently designated the Marvin Bower Fellow at Harvard Business School for two years, he is also the Coxe Distinguished Professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. The Coxe Distinguished Professorship is a new Dartmouth-wide faculty chair. He was the first Professor in Residence and Chief Innovation Consultant at General Electric. He worked with GE’s CEO Jeff Immelt to write How GE is Disrupting Itself, the Harvard Business Review (HBR) article that pioneered the concept of reverse innovation – any innovation that is adopted first in the developing world. HBR picked reverse innovation as one of the Great Moments in Management in the Last Century. In the latest Thinkers 50 Rankings, Govindarajan was ranked the #1 Indian Management Thinker. VG writes about innovation and execution on several platforms including Harvard Business Review and Bloomberg BusinessWeek. He is a co-leader of a global initiative to design a $300 House. Govindarajan has been identified as a leading management thinker by influential publications including: Outstanding Faculty, named by Business Week in its Guide to Best B-Schools; Top Ten Business School Professor in Corporate Executive Education, named by Business Week; Top Five Most Respected Executive Coach on Strategy, rated by Forbes; Top 50 Management Thinker, named by The London Times; Rising Super Star, cited by The Economist; Outstanding Teacher of the Year, voted by MBA students. Prior to joining the faculty at Tuck, VG was on the faculties of Harvard Business School, INSEAD (Fontainebleau) and the Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad, India). -

Dr. Vijay Govindarajan Thought-Leader on Strategy and Innovation Author of the International Best Seller Ten Rules for Strategic Innovators

Dr. Vijay Govindarajan Thought-Leader on Strategy and Innovation Author of the International Best Seller Ten Rules For Strategic Innovators Vijay Govindarajan (www.vg-tuck.com) is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on strategy and innovation. He is the Earl C. Daum 1924 Professor of International Business and the Founding Director of the Center for Global Leadership at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. He was the first Professor in Residence and Chief Innovation Consultant at General Electric. VG writes about the business impact of innovation with an emphasis on execution on his blog and through his quarterly newsletter. Govindarajan has been named to a series of lists by influential publications including: Outstanding Faculty, named by Business Week in its Guide to Best B-Schools; Top Ten Business School Professor in Corporate Executive Education, named by Business Week; Top Five Most Respected Executive Coach on Strategy, rated by Forbes; Top 50 Management Thinker, named by The London Times; Outstanding Teacher of the Year, voted by MBA students. Additional accolades include BusinessWeek, which features Govindarajan as one of the “superstar” management thinkers from India. Prior to joining the faculty at Tuck, VG was on the faculties of Harvard Business School and the Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad, India). He has also served as a visiting professor at INSEAD (Fontainebleau, France), the International University of Japan (Urasa, Japan), and Helsinki School of Economics (Helsinki, Finland). The recipient of numerous awards for excellence in research, Govindarajan was inducted into the Academy of Management Journals’ Hall of Fame, and ranked by Management International Review as one of the “Top 20 North American Superstars” for research in strategy and organization. -

The Suntop Media Thinkers 50

THE SUNTOP MEDIA THINKERS 50 Des Dearlove & Stuart Crainer introduce the Thinkers 50 – the 2005 global ranking of business thinkers. Who is the most influential living management thinker? That was the simple question that inspired the original Thinkers 50 in 2001. A lot of hard work and number-crunching later, the answer became the first global ranking of business gurus. The Thinkers 50 2005 provides a completely new ranking. Produced by Suntop Media in association with the European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD), it is the definitive bi-annual guide to which thinkers and ideas are in – and which have been consigned to business history. In the fickle world of business thought-leadership, of course, a lot can change in four years. When we created the Thinkers 50 , it was the first and only global ranking of business gurus. Since then, imitators have appeared. But being first has its advantages: the Thinkers 50 offers a unique snapshot over time of the practices and personalities shaping the world of work and the way we do our jobs. HOW THE RANKINGS SHAKE DOWN So what do the 2005 rankings show? Who are the most influential management thinkers in the post-dot-com, post-Enron business world? And who, among them, is the reigning champion? Had we published the results just two weeks ago, the answer would have been different. Peter Drucker would almost certainly have topped the ranking for the third time in a row. The influence of Peter Ferdinand Drucker on management thinking is immense. Born in Austria but long resident in the US, his work has a breadth and timelessness that makes some of his rivals look trivial by comparison. -

Management and Business Review (MBR) Mission, Plan, and Call for Papers

Management and Business Review (MBR) Mission, Plan, and Call for Papers We are happy to announce the upcoming launch of a new journal, Management and Business Review (MBR). The mission of MBR is to disseminate knowledge that advances management practice and improves the world. We will publish MBR in print as well as online. Visit our website www.mbrjournal.com In contrast to the Harvard Business Review (HBR), which is published by a single school, MBR is the result of a grassroots initiative with a wide participation by many schools and companies. Please see a story on MBR in Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/poetsandquants/2019/10/25/profs-plan-a-rival-to-the-harvard- business-review/#1f1cb0ae10dc We will publish MBR’s first issue of the inaugural volume in August 2020 and the second issue in November 2020. We will distribute their complimentary digital copies to millions of readers. We will share these issues with you so you can share them with anyone you like. Please register yourself, your colleagues in your organization or other organizations, including your dean or your company head, at www.mbrjournal.com so that we can send all of you complimentary digital copies of the four 2020 issues of MBR and share with you more information on MBR. If you have too many email addresses to register manually, you can send them to Kalyan Singhal at [email protected], and we will register them. In January, we will send an e-mail to the community describing how MBR can help every business school to enhance its brand and strengthen its relationships with alumni and the business community. -

Leadership & L Eadership Innovation Conference Presented by September 27, 2012 | 8:45AM - 4:30PM EPCOR CENTRE for the Performing Arts – Jack Singer Concert Hall

Canada’s Leadership & l eadership Innovation Conference presented by September 27, 2012 | 8:45AM - 4:30PM EPCOR CENTRE for the Performing Arts – Jack Singer Concert Hall 1.866.99.ART.OF | the rtof.com WHAT? Building on the success of the SOLD OUT national tour in Canada, this one day conference features five internationally renowned bestselling authors and visionaries, who will share an exciting blend of cutting edge thinking and real world experi- ence on today’s most critical leadership issues. Don’t miss out on your chance to gain a competitive advantage and network with over 1,300 of Canada’s most influential leaders. WHY? Today's leaders have a dynamic role - integrating people and strategy to achieve sustainability and enhance organizational performance in a challenging business environment. The Art of Leadership responds to the fundamental changes that are impacting leadership functions, and the need for information and planning is critical. From practical tips, to innovative strate- gies, The Art of Leadership is designed to teach and provide leaders with directly related, easily applied, and important tools and techniques that can be implemented within any corporate culture. WHEN? Thursday, September 27, 2012 8:45AM - 4:30PM WHERE? EPCOR CENTRE for the Performing Arts – Jack Singer Concert Hall 205 8 Avenue S.E. Calgary, AB T2G 0K9 403.294.7455 AGENDA… www.epcorcentre.org 8:15AM DOORS OPEN 8:45AM – 9:00AM OPENING REMARKS 9:00AM – 10:00AM VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN 10:00AM – 10:25AM NETWORKING BREAK 10:25AM – 11:30AM SUSAN CAIN 11:30AM – 1:00PM LUNCH BREAK 1:00PM – 2:00PM JIM KOUZES 2:00PM – 3:00PM MITCH JOEL 3:00PM – 3:25PM NETWORKING BREAK 3:25PM – 4:30PM MARCUS BUCKINGHAM 1.866.99.ART.OF | the rtof.com Who Should ATTEND… Leadership is an integral part of every company, from a local startup to a multi-national brand it’s the driving force between your people and the execution of your companies strategy. -

Vijay Govindarajan

Vijay Govindarajan Vijay Govindarajan is the Earl C. Daum 1924 Professor of International Business and Director of the William F. Achtmeyer Center for Global Leadership at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. He is also the Faculty Co-Director for the Tuck Global Leadership 2020 Program. For two consecutive years, the Wall Street Journal ranked Tuck as the number one business school in the nation. Professor Govindarajan’s area of expertise is strategy, with particular emphasis on strategic innovation, industry transformation, and global strategy and organization. Professional credits include: Outstanding Faculty, named by Business Week in its Guide to Best B-Schools; Top Ten Business School Professor in Corporate Executive Education, named by Business Week; and Outstanding Teacher of the Year, voted by MBA students. He was named among the Top 50 Non-Resident Indians of the Year in January 2002 issue of NRI World, the lifestyle and business magazine for Indians living abroad. Prior to joining the faculty at Tuck, Professor Govindarajan was on the faculties of The Ohio State University, and the Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad, India). He has also served as a visiting professor at Harvard Business School, INSEAD (Fontainebleau, France), the International University of Japan (Urasa, Japan), and Helsinki School of Economics (Helsinki, Finland). Professor Govindarajan was ranked by Management International Review as one of the Top 20 North American Superstars for research in strategy and organization. One of his papers was recognized as “one of the ten most-often cited articles” in the entire 40-year history of the prestigious Academy of Management Journal. -

Vijay Govindarajan Speaker Profile

Vijay Govindarajan Internationally Renowned Authority on Innovation and Strategy CSA CELEBRITY SPEAKERS Vijay Govindarajan is widely regarded as one of the world's leading experts on strategy and innovation. Vijay, a The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, Best Selling author, is the Coxe Distinguished Professor at Dartmouth College's Tuck School of Business and the Marvin Bower Fellow at Harvard Business School. "Vijay has been identified as a leading management thinker by the most influential publications In detail Languages He was the first Professor in Residence and Chief Innovation He presents in English. Consultant at General Electric. Prior to joining the faculty at Tuck, Vijay was on the faculties of Harvard Business School, INSEAD Want to know more? (Fontainebleau) and the Indian Institute of Management Give us a call or send us an e-mail to find out exactly what he (Ahmedabad, India). He worked with GE's CEO Jeff Immelt to could bring to your event. write 'How GE is Disrupting Itself', the Harvard Business Review article that pioneered the concept of reverse innovation - any How to book him? innovation that is adopted first in the developing world. Harvard Simply phone, fax or e-mail us. Business Review picked reverse innovation as one of the Great Moments in Management in the Last Century. In the latest Video Thinkers 50 Rankings, Vijay was ranked the #1 Indian Management Thinker and #3 of the world's most influential Publications business thinkers. He is also the recipient of numerous awards for 2016 excellence in research, including the 2015 AMCF Carl S.