Accounting Historians Journal, 2002, Vol. 29, No. 1 [Whole Issue]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

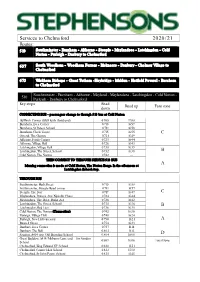

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford 637 South Woodham - Woodham Ferrers - Bicknacre - Danbury - Chelmer Village to Chelmsford 673 Wickham Bishops - Great Totham -Heybridge - Maldon - Hatfield Peverel - Boreham to Chelmsford Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Mayland - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - 510 Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford Key stops Read Read up Fare zone down CONNECTING BUS - passengers change to through 510 bus at Cold Norton Bullfinch Corner (Old Heath Road end) 0708 1700 Burnham, Eves Corner 0710 1659 Burnham, St Peters School 0711 1658 Burnham, Clock Tower 0715 1655 C Ostend, The George 0721 1649 Althorne, Fords Corner 0725 1644 Althorne, Village Hall 0726 1643 Latchingdon, Village Hall 0730 1639 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0732 1638 B Cold Norton, The Norton 0742 -- THEN CONNECT TO THROUGH SERVICE 510 BUS A Morning connection is made at Cold Norton, The Norton Barge. In the afternoon at Latchingdon School stop. THROUGH BUS Southminster, High Street 0710 1658 Southminster, Steeple Road corner 0711 1657 Steeple, The Star 0719 1649 C Maylandsea, Princes Ave/Nipsells Chase 0724 1644 Maylandsea, The Drive, Drake Ave 0726 1642 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0735 1636 B Latchingdon, Red Lion 0736 1635 Cold Norton, The Norton (Connection) 0742 1630 Purleigh, Village Hall 0748 1624 Purleigh, New Hall vineyard 0750 1621 A Runsell Green 0754 1623 Danbury, Eves Corner 0757 1618 Danbury, The -

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

An Archaeological Evaluation by Trial-Trenching at Scotts Farm, Lodge Lane, Purleigh, Essex October 2011

An archaeological evaluation by trial-trenching at Scotts Farm, Lodge Lane, Purleigh, Essex October 2011 report prepared by Adam Wightman on behalf of Richard Emans CAT project ref.: 11/10a NGR: TL 582719 202572 ECC project code: PUSF11 Colchester and Ipswich Museums accession code: COLEM 2011.72 Colchester Archaeological Trust 12 Lexden Road, Colchester, Essex CO3 3NF tel.: (01206) 541051 (01206) 500124 email: [email protected] CAT Report 618 December 2011 Contents 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction 1 3 Archaeological background 1 4 Aim 2 5 Results 2 6 Finds, by Stephen Benfield 4 7 Discussion 6 8 Archive deposition 6 9 Acknowledgements 7 10 References 7 11 Glossary 7 12 Appendix 1: contents of archive 9 Figures after p 10 ECC summary sheet List of plates and figures Frontispiece: General view of the modern front cover farmhouse with T2 in the foreground. Plate 1: T1, view north. 3 Plate 2: T2, view north-east. 3 Plate 3: T3, view south-east. 4 Fig 1 Site location. Fig 2 Site plan. Fig 3 Results. Fig 4 T1, F7: sections; T1-T3: representative sections. CAT Report 618: Archaeological evaluation by trial-trenching at Scotts Farm, Lodge Lane, Purleigh, Essex: October 2011 1 Summary During an evaluation by three trial-trenches at Scotts Farm, Purleigh, Essex, features associated with the modern farmhouse as well as the post-medieval phase of the farm were identified. The farmhouse of the post-medieval phase is shown on the 1st edition OS map of 1881 to the west of the current building. No evidence was found for the medieval farmhouse having stood on the site of the present farmhouse. -

Flooding Emergency Response Plan – April 2014

Flooding Emergency Response Plan – April 2014 Essex has experienced the longest sustained period of wet weather for many years and the County Council has released an additional £1m of emergency revenue funding to deal with highways related flooding. In mid-February 2014, each of the 12 districts in Essex were invited to put forward their top 5 flooding sites for their respective administrative areas, together with any background information. Some of the sites were already well known to Essex Highways due to regular flooding events after prolonged and heavy periods of rainfall. Other sites were not so well known and detailed investigation was therefore required at an early stage. In addition to the top flooding sites listed below, further known flooding defects have been attended to between mid-February and the end of April 2014. These have mainly consisted of blocked gullies, associated pipework and culverts. Some of these have been resolved with no further action required and some requiring a repair. The work is ongoing. A number of longer-term Capital schemes have been identified that will take longer to programme and deliver. The sites that were put forward for action were: Basildon – 6 sites A129 Southend Road, Billericay Kennel Lane, Billericay Cherrydown East, Basildon Roundacre/Cherrydown/The Gore, Billericay Outwood Common Road, Billericay A129 London Road, Billericay Braintree – 13 sites A120, Bradwell Village A131, Bulmer Church Street, Bocking Leather Lane/North Road & Highfields, Great Yeldham London Road, Black Notley B1256 -

Town/ Council Name Ward/Urban Division Basildon Parish Council Bowers Gifford & North

Parish/ Town/ Council Name Ward/Urban District Parish/ Town or Urban Division Basildon Parish Council Bowers Gifford & North Benfleet Basildon Urban Laindon Park and Fryerns Basildon Parish Council Little Burstead Basildon Urban Pitsea Division Basildon Parish Council Ramsden Crays Basildon Urban Westley Heights Braintree Parish Council Belchamp Walter Braintree Parish Council Black Notley Braintree Parish Council Bulmer Braintree Parish Council Bures Hamlet Braintree Parish Council Gestingthorpe Braintree Parish Council Gosfield Braintree Parish Council Great Notley Braintree Parish Council Greenstead Green & Halstead Rural Braintree Parish Council Halstead Braintree Parish Council Halstead Braintree Parish Council Hatfield Peverel Braintree Parish Council Helions Bumpstead Braintree Parish Council Little Maplestead Braintree Parish Council Little Yeldham, Ovington & Tilbury Juxta Clare Braintree Parish Council Little Yeldham, Ovington & Tilbury Juxta Clare Braintree Parish Council Rayne Braintree Parish Council Sible Hedingham Braintree Parish Council Steeple Bumpstead Braintree Parish Council Stisted Brentwood Parish Council Herongate & Ingrave Brentwood Parish Council Ingatestone & Fryerning Brentwood Parish Council Navestock Brentwood Parish Council Stondon Massey Chelmsford Parish Council Broomfield Chelmsford Urban Chelmsford North Chelmsford Urban Chelmsford West Chelmsford Parish Council Danbury Chelmsford Parish Council Little Baddow Chelmsford Parish Council Little Waltham Chelmsford Parish Council Rettendon Chelmsford Parish -

The Economic History of England

Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Archaeological Investigation at the Bell Public House, the Street, Purleigh, Essex Phase I: Trial-Trenching

Archaeological investigation at The Bell Public House, The Street, Purleigh, Essex Phase I: trial-trenching October 2014 Report prepared by Mark Baister on behalf of Mr and Mrs Webb CAT project ref: 14/10b NGR: TL 84216 02032 HEA code: PUB14 Colchester Archaeological Trust Roman Circus House, Roman Circus Walk, Colchester, Essex CO2 7GZ Tel: 07436273304 E-mail: [email protected] CAT Report 815 February 2015 Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Introduction 1 3. Archaeological background 1 4. Aim 1 5. Methodology and Results 1 6. Finds 2 7. Discussion 2 8. Acknowledgements 2 9. References 3 10. Glossary and abbreviations 3 11. Contents of archive 3 12. Archive deposition 4 Figures after p 4 EHER Summary Sheet List of Figures Fig. 1 Site location. Fig. 2 Evaluation results. Fig. 3 Representative sections of T1 and T2. List of Plates Cover – Site view, facing south-west. 1. Summary This is the first half of a report detailing archaeological work undertaken within the vicinity of The Bell Public House, The Street, Purleigh, Essex (Fig. 1). Two trial trenches were excavated on the site of a new proposed car park and store. Three shallow post-medieval/modern features were uncovered, as well as one extensive modern service. Nothing of archaeological interest was uncovered. 2. Introduction (Fig 1) This is the report on the trial-trenching carried out by Colchester Archaeological Trust (CAT) on land opposite The Bell Public House, The Street, Purleigh, Essex (Area 1 - Fig. 1, TL 84216 02032), on the 13th October 2014. The work was commissioned by Mr and Mrs Webb following the direction of a brief prepared by Maria Medlycott, Historic Environment Advisor for Essex County Council (December 2013). -

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ALTHORNE ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS AUSTRAL WAY UNCLASSIFIED BARNES FARM DRIVE PRIVATE ROAD BRIDGEMARSH LANE PRIVATE ROAD BURNHAM ROAD B ROAD CHESTNUT FARM DRIVE PRIVATE ROAD CHESTNUT HILL PRIVATE ROAD DAIRY FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED FAMBRIDGE ROAD B ROAD GARDEN CLOSE UNCLASSIFIED GREEN LANE CLASS III HIGHFIELD RISE UNCLASSIFIED LOWER CHASE PRIVATE ROAD MAIN ROAD B ROAD OAKWOOD COURT UNCLASSIFIED RIVER HILL PRIVATE ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD B ROAD STATION ROAD PRIVATE ROAD SUMMERDALE UNCLASSIFIED SUMMERHILL CLASS III SUNNINGDALE ROAD PRIVATE ROAD THE ENDWAY CLASS III UPPER CHASE PRIVATE ROAD WOODLANDS UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 23 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: ASHELDHAM ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS BROOK LANE PRIVATE ROAD GREEN LANE CLASS III HALL ROAD UNCLASSIFIED RUSHES LANE PRIVATE ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD B ROAD SOUTHMINSTER ROAD UNCLASSIFIED TILLINGHAM ROAD B ROAD TOTAL 7 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: MALDON Information Correct at : 01-APR-2018 PARISH NAME: BRADWELL-ON-SEA ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS BACONS CHASE PRIVATE ROAD BACONS CHASE UNCLASSIFIED BATE DUDLEY DRIVE UNCLASSIFIED BRADWELL AIRFIELD PRIVATE ROAD BRADWELL ROAD B ROAD BRADWELL ROAD CLASS III BUCKERIDGE -

The "King" Family

23 third, sable t on a chevron between three towers, argent, as many fleur de lis, or, for Berill." The "three eagles" description is curious as inanother part of the same Visitation the number of eagles displayed is distinctly stated to be "two." Itis quite probable that the then Herald carelessly wrote the word "three" instead of "two," as all early drawings of the arms only show the two eagles. The eagles, however, sometimes are drawn with one, and sometimes with two necks, but no explanation of this variation has as yet been unearthed. An extensive Pedigree of this prominent Essex King family has been compiled, after an almost exhaustive examination of all the early records, wills,etc., of Essex County. The first ancestor of record appears to have been John Kynge of Dompnar inBurnham, Co. Essex, who died in 1490, leaving a will,and known issue, John, Richard, Thomas and Joan. John Kynge (John) of Althorne, Essex, called "John Kynge by West," probably to distinguish him from another John Kynge, (either a brother or a near relative) was an extensive land owner and died in 1524 leaving a willand known issue, William,Robert "Second sonne," John, Emme and Elynor. William Kynge (John, John) of Great Baddow, Essex, owned extensive lands inBurnham, Mayland and Althorne and died in 1570 leaving a will. He married Cicely ,and had known issue, Thomas,* Abraham, John "youngest son," and Priscilla. His son Thomas Kynge has been indentified as that Thomas Kynge of Purleigh, Essex, who died in 1588 leaving a will. By his wife Anne, he had known issue, Christopher, Edward, George and a daughter who married Thomas Hastier. -

The Parochial Church Councils of the Ten Villages

THE PAROCHIAL CHURCH COUNCILS OF THE TEN VILLAGES St Mary the Virgin, High Easter St Andrew’s, Good Easter St Margaret’s, Margaret Roding St Mary the Virgin, Great Canfield All Saints, High Roding St Mary the Virgin, Aythorpe Roding South Rodings – Leaden Roding, White Roding, Abbess Roding and Beauchamp Roding Data Privacy Notice 1. Your personal data – what is it? Personal data relates to a living individual who can be identified from that data. Identification can be by the information alone or in conjunction with any other information in, or likely to come into our possession. The processing of personal data is covered by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which comes into force on 25 May 2018. In this statement we explain how we will use your data, provide an overview of your rights and indicate where you can get further information from. 2. Who are we? The villages of the Rodings, Easters and Great Canfield consist of 10 village churches, three benefices and seven Parochial Church Councils, (PCCs). Each of the PCCs is a ‘Data Controller’ for the administration of the parishes and the Parish Priest is a ‘Data Controller’ for pastoral care within the parishes. In this privacy statement, “we” may refer to either the PCCs (and its employees or volunteers) or the Parish Priest. The parishes are currently split into two historic groups; The Six Parishes with six individual PCCs, (High Easter, Good Easter, Margaret Roding, Great Canfield, High Roding and Aythorpe Roding) and The South Rodings which is a single parish with one PCC (Leaden Roding, White Roding, Abbess Roding and Beauchamp Roding). -

Crouch and Roach Estuary Management Plan

THE CROUCH AND ROACH ESTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN THE CROUCH AND ROACH ESTUARY IS REMOTE AND BEAUTIFUL IT HAS A CHARM OF ITS OWN AND IT DESERVES TO BE CHERISHED Choose a greener Essex. Eating local food reduces greenhouse gas emissions and supports our local economy. Find out more about a greener Essex - visit http://www.agreeneressex.net Page nos. CONTENTS 1- 4 A. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FOREWORD 5 - 7 A.1. Foreword by Councillor John Jowers, Cabinet Member for Localism, Essex County Council A.2. acknowledgements B. THE VISION AND OBJECTIVES 8 - 9 B.1. The Vision B.2. The Principle Objectives Guiding the Crouch and Roach Estuary Management Plan C. INTRODUCTION 10-14 C.1. The Crouch and Roach Estuary System C.2. Integrated Coastal Zone Management C.3. Essex Estuary Management Plans C.4. The Crouch and Roach Estuary Management Plan C.5. Aims of the Crouch and Roach Estuary Management Plan C.6. Crouch and Roach Estuary Management Plan – Geographical Area Covered C.7. The Crouch and Roach Estuary Project Partners C.8. The Wider Context D. ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK AND LEGAL STATUS 15-18 D.1. Implementation D.2. Links with Existing Strategies D.3. Resource D.4. Monitoring and Evaluation E. LAND OWNERSHIP 19-21 E.1. Total Length of Coastline in kilometres E.2. Crouch Harbour Authority Holding E.3. Crown Estates Property E.4. Ministry of Defence Estates E.5. Other Identified Riverbed Owners E.6. Foreshore Ownership F. THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT AND NATURE CONSERVATION 22-27 F.1. Designations and Protected Areas F.2. -

RODINGS, EASTERS and GREAT CANFIELD ……Serving Our Communities

THE RODINGS, EASTERS and GREAT CANFIELD ……serving our communities St Edmund, Abbess Roding - St Mary the Virgin, Aythorpe Roding - St Botolph, Beauchamp Roding - St Andrew, Good Easter - St Mary the Virgin, Great Canfield - St Mary the Virgin, High Easter - All Saints, High Roding - St Michael and All Angels, Leaden Roding - St Margaret, Margaret Roding - St Martin, White Roding www.thesixparishes.org.uk and www.essexinfo.net/southrodingschurches RODINGS, EASTERS and GREAT CANFIELD …… serving our communities CONTENTS Welcome from the Parishes page 3 Dunmow and Stansted Mission and Ministry Unit page 4 Rural Ministry in the Chelmsford Diocese page 5 About us and where we are today page 6 Who we are looking for page 8 What we do well page 10 Church life page 11 Parish life page 13 The Rectory page 15 Appendix 1 – Centre for Rural Excellence page 16-18 Aythorpe Roding High Roding Great Canfield High Easter White Roding Good Easter Abbess Roding Beauchamp Roding Leaden Roding Margaret Roding 2 RODINGS, EASTERS and GREAT CANFIELD …… serving our communities WELCOME Thank you for taking the time to look at our Parish Profile. We are a group of rural parishes set in the very heart of beautiful mid-Essex countryside and part of the Dunmow and Stansted Deanery, a licensed Mission and Ministry Unit which allows us to work closely together to share resources and develop ministry. We hope the pages that follow will give you some insight into our communities, together with the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead for us as we continue to move forward in a new chapter of shared ministry.