Pygmalion Eprogram PDF for Printing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 98, 1978-1979

five 98th SEASON ffM^ y) BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director I X ^iimini £S&t- J " ,*> f~~~ IfflM ' v. * WM »* Spend some time with a Little Witch tonight, Ilk Strega means witch. Strega also means a bewitching golden liqueur you can sip and savor and spend some time with. Without ever tiring of its magically unique taste. A taste, legend has it, created centuries ago in Italy by the beautiful witches of Benevento. Enjoy Strega straight, on-the-rocks, or mixed in a Little Witch. Truly, a haunting brew. I «> Imported from Italy, Eighty Proof, by Schenley Imports Co., NY, NY © 1977 Ifthis wasn't a black &white ad, we could show you what Faille's InteriorDesigners can dowith color. We have assembled a talented group of men and women to work with you on your decorating and redecorating plans. One room or many, traditional or modern, they will share their creative ideas with you. There is no added charge for this designer service. For information, please call Mrs. Scully at PAINE 426-1500, extension 156. FURNITURE jisy ZfiQfftJKJ 3HSH Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Ninety-Eighth Season 1978-1979 The Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. Talcott M. Banks, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Philip K.Allen, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President John L. Thorndike, Vice-President Abram T. Collier, Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps III Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Irving W. -

New York Pass Attractions

Free entry to the following attractions with the New York Pass Top attractions Big Bus New York Hop-On-Hop-Off Bus Tour Empire State Building Top of the Rock Observatory 9/11 Memorial & Museum Madame Tussauds New York Statue of Liberty – Ferry Ticket American Museum of Natural History 9/11 Tribute Center & Audio Tour Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises (Choose 1 of 5): Best of New York Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum Local New York Favourite National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey - NEW in 2019 The Downtown Experience: Virtual Reality Bus Tour Bryant Park - Ice Skating (General Admission) Luna Park at Coney Island - 24 Ride Wristband Deno's Wonder Wheel Harlem Gospel Tour (Sunday or Wednesday Service) Central Park TV & Movie Sites Walking Tour When Harry Met Seinfeld Bus Tour High Line-Chelsea-Meatpacking Tour The MET: Cloisters The Cathedral of St. John the Divine Brooklyn Botanic Garden Staten Island Yankees Game New York Botanical Garden Harlem Bike Rentals Staten Island Zoo Snug Harbor Botanical Garden in Staten Island The Color Factory - NEW in 2019 Surrey Rental on Governors Island DreamWorks Trolls The Experience - NEW in 2019 LEGOLAND® Discovery Center, Westchester New York City Museums Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET) The Met: Breuer Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Whitney Museum of American Art Museum of Sex Museum of the City of New York New York Historical Society Museum Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Museum of Arts and Design International Center of Photography Museum New Museum Museum of American Finance Fraunces Tavern South Street Seaport Museum Brooklyn Museum of Art MoMA PS1 New York Transit Museum El Museo del Barrio - NEW in 2019 Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust Museum of Chinese in America - NEW in 2019 Museum at Eldridge St. -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues). -

The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-5-2016 The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda Juanita Ulloa Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Ulloa, Juanita, "The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 339. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2016 JUANITA ULLOA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE SONGS OF MEXICAN NATIONALIST, ANTONIO GOMEZANDA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Juanita M. Ulloa College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music Department of Voice May, 2016 This Dissertation by: Juanita M. Ulloa Entitled: The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Visual and Performing Arts, School of Music, Department of Voice Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ____________________________________________________ Dr. Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Paul Elwood, Ph.D., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Professor Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Weis, Ph.D., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense . Accepted by the Graduate School ____________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

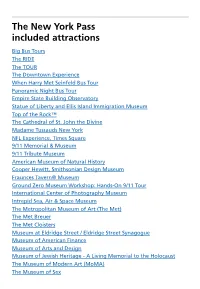

The New York Pass Included Attractions

The New York Pass included attractions Big Bus Tours The RIDE The TOUR The Downtown Experience When Harry Met Seinfeld Bus Tour Panoramic Night Bus Tour Empire State Building Observatory Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island Immigration Museum Top of the Rock™ The Cathedral of St. John the Divine Madame Tussauds New York NFL Experience, Times Square 9/11 Memorial & Museum 9/11 Tribute Museum American Museum of Natural History Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Fraunces Tavern® Museum Ground Zero Museum Workshop: Hands-On 9/11 Tour International Center of Photography Museum Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) The Met Breuer The Met Cloisters Museum at Eldridge Street / Eldridge Street Synagogue Museum of American Finance Museum of Arts and Design Museum of Jewish Heritage - A Living Memorial to the Holocaust The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) The Museum of Sex Museum of the City of New York Museum of the City of New York New Museum New York Historical Society The Paley Center for Media The Skyscraper Museum Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum South Street Seaport Museum Whitney Museum of American Art MoMA PS1 New York Hall of Science Brooklyn Museum New York Transit Museum Staten Island Children’s Museum Staten Island Museum at Snug Harbor and in St. George New York Botanical Garden Brooklyn Botanic Garden Snug Harbor Cultural Center & Botanical Garden Staten Island Zoo Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises Midtown Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises Downtown New York Water Taxi, Hop On Hop Off Ferry: All-Day Access -

Circling Opera in Berlin by Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College

Circling Opera in Berlin By Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College, 2001 A.M., Brown University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in the Department of Music at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 This dissertation by Paul Martin Chaikin is accepted in its present form by the Department of Music as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_______________ _________________________________ Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Jeff Todd Titon, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Philip Rosen, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Dana Gooley, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Deutsche Akademische Austauch Dienst (DAAD) for funding my fieldwork in Berlin. I am also grateful to the Institut für Musikwissenschaft und Medienwissenschaft at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin for providing me with an academic affiliation in Germany, and to Prof. Dr. Christian Kaden for sponsoring my research proposal. I am deeply indebted to the Deutsche Staatsoper Unter den Linden for welcoming me into the administrative thicket that sustains operatic culture in Berlin. I am especially grateful to Francis Hüsers, the company’s director of artistic affairs and chief dramaturg, and to Ilse Ungeheuer, the former coordinator of the dramaturgy department. I would also like to thank Ronny Unganz and Sabine Turner for leading me to secret caches of quantitative data. Throughout this entire ordeal, Rose Rosengard Subotnik has been a superlative academic advisor and a thoughtful mentor; my gratitude to her is beyond measure. -

T,' H".I,Mt.I-Ii'.N Ij .'J~:I¡;'Ii ,@

~~~ T,' H".I,mT.I-Ii'.N ij .'j~:i¡;'ii ,@ (i; ~~~ T. ¡'"H." "l,m.T. ..'......E...~ rN' WLIW:~ì. ; i\ 'j; v NET.ORG is a House of Ideas. A luminous destination in the media landscape. From the streets and neighborhoods of New York City to the far reaches of AmericaJ this vibrant institution invites people to see in new ways, to be touched by creativity and inspiration, to revel in discovery and wonder. Built on a mission to educate, celebrate, innovateJ and inspire, this House of Ideas promotes a vision of people more deeply connected to the world around them. During 2008-09, WNET.ORG harnessed the highest potential of public media in pursuit of its mission. Through its array of broadcast and online outlets, it reported the news of the day. opened channels of dialogue on critical issues facing American citizensJ showcased the artists that define the pinnacle of cultural expression in our timeJ and made opportunities for lifelong learning available to all. All that WNET.ORG undertakes is made possible by the generous support of individuals and organizations that believe in our mission. In this reportJ we look back at some of the highlights from the House of Ideas during the year 2008-09. Here, we also recognize the vital contributions of those supporters who have empowered our unique vision. Thanks to their commitment, our mission-driven media continues to touch the minds and hearts of millions every day. z o ~INSPIRE -~ PEOPLE OF ALL AGES AND WALKS OF LIFE WITH MEDIA THAT IS , POWERFUL, RESONANT AND UNIQUE. -

Nyc & Company Invites New Yorkers to Discover Times

NYC & COMPANY INVITES NEW YORKERS TO DISCOVER TIMES SQUARE NOW AND REVITALIZE THE CROSSROADS OF THE WORLD ——Earn Up to $100 Back and Enjoy Savings at Iconic Hotels, Museums, Attractions, Restaurants and More at Participating “All In NYC: Neighborhood Getaways” Businesses —— New York City (October 26, 2020) — NYC & Company, the official destination marketing organization and convention and visitors bureau for the CONTACTS five boroughs of New York City, is inviting New Yorkers to take an “NYC- Chris Heywood/ cation” at the Crossroads of the World, in the heart of Times Square. With Britt Hijkoop many deals to take advantage of, now is an attractive time to take a staycation NYC & Company 212-484-1270 in Times Square and the surrounding blocks, to visit some of the most iconic [email protected] hotels, attractions, museums, shopping and dining that Midtown Manhattan has to offer. Mike Stouber Rubenstein 732-259-9006 While planning an “NYC-cation” in Times Square, New Yorkers are [email protected] encouraged to explore NYC & Company’s latest All In NYC: Staycation DATE Guides and earn up to $100 in Mastercard statement credits by taking October 26, 2020 advantage of the All In NYC: Neighborhood Getaways promotion, NYC & Company’s most diverse, flexible and expansive lineup of offers ever, with FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE more than 250 ways to save across the five boroughs. "Now is the time for New Yorkers to re-experience Times Square… for its iconic lights, rich history, hidden gems, world-renowned dining and unique branded retail and attractions. While we can’t travel out, we should seize this moment and take advantage of the Neighborhood Getaway deals to book a hotel and play tourist with an ‘NYC-cation’ at the Crossroads of the World,” said NYC & Company President and CEO Fred Dixon. -

Departmental Programs 2009

1 Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 3/20/2012 Departmental Programs 2009 Spring 2009 Seminar January 29, 2009 Trk. 1 Arabesque No. 1 (Claude Debussy) Quodesia Johnson, piano Trk. 2 Sonata in g minor, Op. 49 No. 1 (Beethoven) Christopher Jackson, piano Trk. 3 Variations on Cobbler’s Bench (Arthur Frackenpohl) Ronald Floyd, tuba Seminar February 5, 2009 Trk. 1 Concert Etude in D-flat Major “Un Sospiro” (Franz Liszt) Dr. Vicki A. Seldon, piano Trk. 2 Russian Sailor’s Dance (Reinhold Gliére) Kristopher Gentry, euphonium Seminar February 19, 2009 Trk. 1 Lied der Mignon (Schubert) Laura Patterson, soprano Trk. 2 Waltz Theme (from Sleeping Beauty) (Tschaikowsky) Michael Foucher, clarinet Trk. 3 Scherzino (Walter Hartley) Anthony Terrell, euphonium Trk. 4 Suite for Tuba (Don Haddad) Ron Darius Wynn, bass trombone Mvt, II Trk. 5 City Signs: A Spiritual Walk Through the City (Robert Morris Imani Anderson, Class of ’95, soprano No Money Down: I’m Glad Salvation is Free Security System Engaged: He Sees All You Do Rent to Own: King Jesus Will Be Mine Seminar February 26, 2009 Trk. 1 Allerseelen (Strauss) Jessica Simmons, soprano Trk. 2 Prelude in g minor, Op. 28, No. 22 (Frederic Chopin) Jasmine Brock, piano Seminar March 5, 2009 2 Trk. 1 Sonata in c minor, Op. 10 No. 1 (Beethoven) Kristina Gentry, piano Allegro molto e con brio Trk. 2 If Thou Be Near (J.S. Bach) James Dodd, tuba Trk. 3 Sonata in b minor, BWV 1030 (J.S. Bach) John Lockett, flute Trk. 4 Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (Camille Saint-Saens) Jeffrey Opaleye, clarinet Lento Trk. -

La Vie Bp Iiib

bo IlIa. Phrase (1:06) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago La vie bp IIIb. Antique (1:55) Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foun- dation devoted to promoting the finest musicians bq IV. Royauté (1:44) est une and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago br V. Marine (1:02) Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are sup- ported in part by contributions and grants from indi- bs VI. Interlude (2:14) viduals, foundations, corporations, and government bt VII. Being Beauteous (3:48) agencies including the Alphawood Foundation, the parade Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Patrice Michaels, soprano ck VIII. Parade (2:56) Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. *The Chicago Chamber Musicians cl IX. Départ (1:44) **Czech National Symphony Orchestra / Paul Freeman, conductor Producer: James Ginsburg Germaine Tailleferre* Engineer: Bill Maylone from Chansons du Folklore de France Recorded: Erik Satie (1866–1925) / Easley Blackwood (b. 1933)* cm La pernette se lève (3:21) November 5, 11 & 12, 2000 (with CNSO) 1 La Diva de l’Empire (1904) (2:50) cn Suzon va dire à sa mère (1:13) March 25 & 26, 2002 (with CCM) 2 Je te veux (1901) (5:00) co L’autre jour en m’y promenant (2:22) Photos of Patrice Michaels: cp A Genn’villiers (1:47) McArthur Photography cq Erik Satie / Robert Caby (1905–1992)** Jean de la Réole (1:27) Design: Melanie Germond and Pete Goldlust 3 Le chapelier (from Trois Mélodies de 1916) (0:35) 4 Les anges (from Trois Mélodies de 1886) (1:53) Erik Satie / Robert Caby** Translations: -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990, Subscription

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SBJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 109TH SEASON 1989-90 ^r^ After the show, enjoy the limelight. Tanqueray. A singular experience. Imported English Gin, 47.3% Alc/Vol (94.6°). 100% Grain Neutral Spirits. © 1988 Schieffelin & Somerset Co., New York, N.Y. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Ninth Season, 1989-90 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Geary Mrs. John L. Grandin Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Francis W. Hatch, Jr. Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. Bela T. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John L. Thorndike Abram T. Collier Irving W. Rabb Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. McDonough, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration Kenneth Haas, Managing Director Daniel R.