Carroll Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUARDO DE CARLI.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ EDUARDO DE CARLI DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CAPACIDADES RELACIONAIS EM PROCESSOS DE COOPERAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE-EMPRESA: UM ESTUDO DA ATUAÇÃO DE UNIVERSIDADES FEDERAIS CURITIBA 2018 EDUARDO DE CARLI DESENVOLVIMENTO DE CAPACIDADES RELACIONAIS EM PROCESSOS DE COOPERAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE-EMPRESA: UM ESTUDO DA ATUAÇÃO DE UNIVERSIDADES FEDERAIS Tese de Doutorado elaborada como requisito parcial à obtenção do Título de Doutor em Administração no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração, Setor de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Andréa Paula Segatto CURITIBA 2018 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELA BIBLIOTECA DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS APLICADAS – SIBI/UFPR COM DADOS FORNECIDOS PELO(A) AUTOR(A) Bibliotecário: Eduardo Silveira – CRB 9/1921 De-Carli, Eduardo Desenvolvimento de capacidades relacionais em processos de cooperação universidade-empresa: um estudo da atuação de universidades federais / Eduardo De Carli. 2018. 145 p. Tese (Doutorado) - Universidade Federal do Paraná. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração, do Setor de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas. Orientadora: Andréa Paula Segatto. Defesa: Curitiba, 2018 1. Cooperação universitária 2. Empresas. 3. Capacidade. I. Universidade Federal do Paraná. Setor de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração. II. Segatto, Andréa Paula. III. Titulo. CDD 650.071 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO Dedico este trabalho para minha família e a todos que, de alguma forma, contribuíram para que exista. AGRADECIMENTOS À mim mesmo. Muito obrigado, Eduardo! Sem você isso não existiria. À todos vocês que me fizeram companhia, me ajudaram, me fizeram pensar na vida e me dedicaram um pedacinho de seu tempo e vida merecem meu carinho. Espero não ter esquecido de ninguém. À professora Andréa Paula Segatto, pela orientação, pelo carinho de ter me aceito como seu orientando desde a época do mestrado, pela confiança, pela amizade construída no decorrer desses anos de convivência. -

A Comeback for Dawn Harper Nelson Delayed

Track & Field News January 2021 — 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 74, No. 1 January 2021 From The Editor — What? There’s No 2020 World Rankings?! . 4 T&FN’s 2020 Podium Choices . 5 — T&FN’s 2020 World Men’s Track Podiums — . 6 — T&FN’s 2020 World Men’s Field Podiums — . 10 T&FN’S 2020 Men’s MVP — Mondo Duplantis . 15 Mondo Duplantis Figures He Still Has Many Years To Go . 16 — T&FN’s 2020 World Women’s Track Podiums — . 18 — T&FN’s 2020 World Women’s Field Podiums — . 22 T&FN’S 2020 Women’s MVP — Yulimar Rojas . 27 T&FN’s 2020 U .S . MVPs — Ryan Crouser & Shelby Houlihan . 28 Focus On The U .S . Women’s 100 Hurdles Scene . 29 Keni Harrison Looking For Championships Golds . 31 Brianna McNeal Ready To Defend Her Olympic Title . 33 A Comeback for Dawn Harper Nelson Delayed . 34 Sharika Nelvis Keeps On Moving Forward . 35 Christina Clemons Had A Long Road Back . 36 T&FN Interview — Grant Holloway . 37 Track News Digest . 41 Jenna Hutchins Emerges As The Fastest HS 5000 Runner Ever . 43 World Road Digest . 45 U .S . Road Digest . 46 Analysis: The Wavelight Effect . 47 Seb Coe’s Pandemic-Year Analysis . 51 STATUS QUO . 55 ON YOUR MARKS . 56 LAST LAP . 58 LANDMARKS . 61 FOR THE RECORD . 62 CALENDAR . 63 • cover photo of Mondo Duplantis by Jean-Pierre Durand • Track & Field News January 2021 — 3 FROM THE EDITOR Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 — What? There’s No Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. -

County of Marin Community Development Agency Building and Safety Division

County of Marin Community Development Agency Building and Safety Division PERMITS ISSUED FOR WEEK ENDING SATURDAY, APRIL 30TH, 2016 Owner Contractor Address Parcel # Construction Value Jensen Matthew & OWNER 276 Flamingo Rd Mill Valley 052-022-03 (21,23) Addn;Rmdl $50,000 Block David J R C ROOFING 436 Laverne Ave Mill Valley 047-112-57 (53) Tear-Off & R $19,450 Minton Pamela /Tr/ RENEWAL BY ANDERSEN 50 Buena Vista Ave Fairfax 197-033-27 (58) Repl Patio D $13,502 Ellison Jane S /Tr/ WEDGE ROOFING, INC 42 Crestview Way San Rafael 180-192-37 (53) Reroof $6,610 Woodson Kirby M WEDGE ROOFING, INC 650 Ridgewood Ave Mill Valley 047-032-04 (53) Reroof E-Ins $53,071 Nguyen Deborah & Knight OWNER/BUILDER 533 Pine Crest Rd Mill Valley 050-061-27 (22) Struc Remod $80,000 Wong Scott K & Kim Sera HENDRICKSON POOLS, INC. 1 Starboard Ct Mill Valley 043-101-14 (10) Pool Remodel $20,000 Wong Scott K & Kim Sera HENDRICKSON POOLS, INC. 1 Starboard Ct Mill Valley 043-101-14 (10) Spa $30,000 Wong Scott K & Kim Sera HENDRICKSON POOLS, INC. 1 Starboard Ct Mill Valley 043-101-14 (11,13) Ret Wall $50,000 Giacomini Andrew & HENDRICKSON POOLS, INC. 501 Meadow Way San Geronimo 169-061-05 (10) Pool $70,000 Ross Val Storage Assoc WORLD EXTERIORS INC 890 College Ave #C Kentfield 074-031-76 (53) Re-Roof $48,000 Ross Val Storage Assoc WORLD EXTERIORS INC 890 College Ave #B Kentfield 074-031-76 (53) Re-Roof $38,000 Malaney Michael C /Tr/ Et J S CONSTRUCTION 31 Kailua Way Dillon Beach 100-271-12 (22,23,58) Rmdl 1 $42,500 Ruth Carol CHARLES WINDOW AND DOOR 224 Roundtree Way San Rafael 164-511-65 (58) Repl 2 Windo $4,000 Heblack George & Joan 20 NEIGHBORS ROOFING 35 Mt Lassen Dr San Rafael 164-422-08 (53) Reroof $13,600 Judkins Bryan D & Jennife VALENTINE CORP. -

Last Name First Name Amount City State Betat Darlene 50.00

End Citizens United//Let America Vote Action Fund January 2021 Contributions Last Name First Name Amount City State Betat Darlene $ 50.00 Portland OR David Denise $ 300.00 La Jolla CA Etienne-Millot Bernadette $ 7.00 Bethesda MD Evans Mary $ 50.00 Pendleton OR HOGAN Edward $ 10.00 Northampton MA Simon Claudia $ 25.00 Midlothian VA Zuanich Janet $ 10.00 Everett WA Page 1 of 1 End Citizens United//Let America Vote Action Fund February 2021 Contributions Last Name First Name Amount City State Badcock Belinda $ 10,000.00 Greenwich CT Bernard Ellen $ 25,000.00 Harrisville NH Bernard Ed $ 25,000.00 Harrisville NH Blair Clancy $ 100.00 Brooklyn NY Block Peter $ 100.00 Cincinnati OH Boogdanian D $ 7.00 Boston MA Brickner Suzanne $ 50.00 Tulsa OK Burday Rachel $ 25.00 Lagrangeville NY Burke Kathleen $ 1,000.00 Tiburon CA Byrd Nora $ 10.00 Houston TX Carolin Robert $ 25.00 San Diego CA Connolly Taylor $ 5.00 Baltimore MD Cormier Brian $ 500.00 Demastus Vicky $ 5.00 Navarre OH Derig Gene $ 10.00 Anacortes WA DuBois Ann $ 1,000.00 Greenwich CT Etienne-Millot Bernadette $ 7.00 Bethesda MD Fidler Josh $ 25,000.00 Naples FL Fidler Genine $ 25,000.00 Naples FL Gold Eva Kay $ 100.00 Portland OR Goldsborough John $ 25.00 Philadelphia PA Groth Stephen $ 5.00 Laguna Beach CA Groundwater Beth $ 500.00 Breckenridge CO Hanavan William $ 1,000.00 Cleveland Heights OH Heintz Stephen $ 250.00 New York NY Hitchcock Jennifer Megan $ 25.00 Richmond VA Hogan Edward $ 10.00 Northampton MA Hohn John $ 100.00 Winston Salem NC Horn Edward $ 10.00 Yonkers NY Ivanov Pavel -

Marriage Certificates

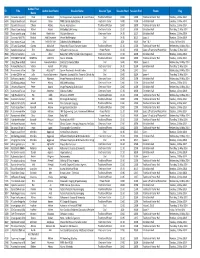

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

A Manual for Performance Measurement

A Manual for Performance Measurement Fairfax County Performance Measurement Team Department of Management and Budget 2009 www.fairfaxcounty.gov/dmb http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/dmb/perf_measure.htm Foreword When the Fairfax County Measures Up manual was first developed for agencies to use in preparing the FY 1999 Budget, it was noted that the first edition would be the first of many maps on the road toward higher performance. Since that time, thousands of County staff have used the manual to develop and improve goals, objectives and performance indicators for the budgets from FY 1999 to FY 2010. The general consensus is that the information regarding program performance continues to improve through better linkage of mission, goals, objectives and indicators, as well as a more balanced picture of performance through the use of the Family of Measures – output, efficiency, service quality and outcome. Once again, these instructions have been updated to reflect additional information available and lessons learned over the past nine years. It is important to note that there are no changes to the methodology. We will continue to use the same process that staff is accustomed to by now, including the efficiency calculation spreadsheet that was introduced for the FY 2000 budget to ensure consistency and accuracy in computing cost per unit. Updates to this manual since then include an expanded section on setting targets, the program logic model, the County’s benchmarking efforts, and how Fairfax County uses performance measurement to improve. Since this effort began, Fairfax County has continued to evolve its approach to continuous improvement, now manifested in the Fairfax Framework for Excellence (FfX) which is based on the High Performance Organization (HPO) model. -

Directory of Teacher Email Addresses

Building Name E_MAIL Last Name First Name Position Name AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] AHIEKPOR KRISTIN INTERVENTION SPECIALIST AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] COUSINO JENNIFER ENGLISH HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] DAUNHAUER AMY SENIOR DIRECTOR AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] DEBERG-PEACE MONICA ASST DIRECTOR ANSAT AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] ELLIS KENDRA ENGLISH HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] HOLMAN WILLIAM T AND I AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] HOOKER MELISSA SCIENCE HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] JURKIEWICZ CASSANDRA SEC IV 10.5 M 8 HR AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] KINNER ANTHONY SOCIAL STUDIES HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] NABER-FISHER GLENELLYN FOREIGN LANGUAGE AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] NEUHAUS TIMOTHY PHYS ED HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] SANZENBACHER LINDSAY SCIENCE HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] SMITH ROBERT INTERVENTION SPECIALIST AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] SWAN CHRISTINE SOCIAL STUDIES HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] WALLER AUSTIN MATH HS AEROSPACE AND NAT SCIENCE ACAD [email protected] YOUNG MAURICE MATH HS ARLINGTON ES [email protected] ACOSTA WENDI KINDERGARTEN ARLINGTON ES [email protected] BARNES KORA CCSE ARLINGTON ES [email protected] BERMEJO CARMEN ELEMENTARY ADMIN ASSIST ARLINGTON ES [email protected] BLUST NATHAN ASST PRINCIPAL ARLINGTON ES [email protected] -

North Carolina Register

)<FM/-7V'3^//*Vf^^Vc I The NORTH CAROLINA REGISTER IN THIS ISSUE IN ADDITION Final Decision Letters Wildlife Resources Commission Proclamation PROPOSED RULES Environment, Health, and Natural Resources Human Resources Justice Nursing, Board of State Personnel ; ^ORT/Tg Transportation RECEIVED «. FINAL RULES CCNi tiomI MAY 6 1992 B II u Human Resources RRC OBJECTIONS P\W. LIBRARY RULES INVALIDATED BY JUDICIAL DECISION CONTESTED CASE DECISIONS ISSUE DATE: MAY 1, 1992 Volume 7 • Issue 3 • Pages 174-331 INFORMATION ABOUT THE NORTH CAROLINA RFGISTFR AND AOMTNTSTRATTVE rODF NORTH CAROLINA REGISTER TEMPORARY RULES Under certain emergency conditions, agencies may issi TTie North Carolina Register is published twice a month and temporary rules. Within 24 hours of submission to OAH, tl contains information relating to agency, executive, legislative and Codifier of Rules must review the agency's written statement judicial actions required by or affecting Chapter 150B of the findings of need for the temporary rule pursuant to the provisions General Statutes. All proposed administrative rules and notices of G.S. 150B-21.1. If the Codifier determines that the findings me public hearings filed under G.S. 150B-21.2 must be published in the criteria in G.S. 150B-21.1, the rule is entered into the NCAC the Register. The Register will typically comprise approximately the Codifier determines that the findings do not meet the criteri fifty pages per issue of legal text. the rule is returned to the agency. The agency may supplement i State law requires that a copy of each issue be provided free of findings and resubmit the temporary rule for an additional revie charge to each county in the state and to various state officials and or the agency may respond that it will remain with its initi institutions. -

ID Title Author First Name Author Last Name Session Name Session

Author First ID Title Author Last Name Session Name Session Type Session Start Session End Room Day Name 4723 Fat‐water separatio Riad Ababneh Fat Suppression, Separation & Quantification Traditional Poster 10:00 12:00 Traditional Poster Hall Tuesday, 13 May 2014 5084 Capsaicin induced Maryam Abaei fMRI: Clinical Applications Electronic Poster 16:00 17:00 Exhibition Hall Tuesday, 13 May 2014 5927 Quantitative cereb Zaheer Abbas Neuro: Applications Traditional Poster 16:00 18:00 Traditional Poster Hall Tuesday, 13 May 2014 4038 Worst‐Case Analys Mahdi Abbasi MR Safety & RF Arrays Electronic Poster 13:30 14:30 Exhibition Hall Thursday, 15 May 2014 7008 Tract‐specific q‐spa Khaled Abdel‐Aziz Multiple Sclerosis Electronic Poster 14:15 15:15 Exhibition Hall Monday, 12 May 2014 6192 Coronary Wall Thic Khaled Abd‐Elmoniem Vessel Wall Imaging Oral 14:15 16:15 Space 3 Monday, 12 May 2014 5882 Non Invasive Quan Inès ABDESSELAM Diabetes & Fat Metabolism Oral 8:00 10:00 Blue 1 & 2Friday, 16 May 2014 1700 DTI and Quantitativ Osama Abdullah Myocardial Tissue Characterization Traditional Poster 13:30 15:30 Traditional Poster Hall Wednesday, 14 May 2014 7922 Gated Compensati Eric Aboussouan Diffusion Controversies Power Poster 13:30 14:30 Space 1/Traditional Poster Hall Thursday, 15 May 2014 4500 Effect of secretin st Julie Absil Body DWI/ MRS/ Female Pelvis Pregnancy Electronic Poster 17:30 18:30 Exhibition Hall Monday, 12 May 2014 4470 POSTMORTEM MR MARTINA ABSINTA Neuro: Methods Traditional Poster 16:00 18:00 Traditional Poster Hall Tuesday, 13 May -

P U R D U E S a L a R I

THE EXPONENT, 2018 PURDUE SALARIES PAGE 1 !"#$ %&'(&)*+,-,'.)+ !"#$%&'() *%$+,) !-./) 0+-&1) 2/+) !34%5+5$) 4$() $/+) $%$-6) .%74+5(-$#%5) 8%&) -66) 5%59($:"+5$) ;5#<+&(#$0) +746%0++(=) 2/#() &+4%&$) #() &+>+.$#<+) %8) +-&5#5?() 8%&) $/+) @ABC) .-6+5"-&)0+-&1)-()4&%<#"+")D0)E:&":+);5#<+&(#$0)#5).%746#-5.+)F#$/)4:D6#.)&+.%&"()6-F(=) 2/#() #((:+) .%5$-#5() 6-($) 5-7+() G9HI) J9K) F#66) D+) #5.6:"+") #5) L%5"-0'() +"#$#%5= PAGE 2 THE EXPONENT, 2018 PURDUE SALARIES How Purdue’s head coach salaries stack up Mitch Daniels STAFF REPORTS gets a raise !"##$%$& '()#$($*& *(+,-$& ."+& %+$'(/ STAFF REPORTS 0$**& 1',#2& ,0& )"3$*& ".& $-$0(4'##2& 3#'2,0%&'&*3"+(&."+&()$,+&5'+$$+6&74(& F,()&()$&?@AB&*'#'+2&%4,1$&"4(6&,(&,*& ()$,+&5"'5)$*&8'9$&'&)$'#()2&#,-,0%& 0":&+$3"+($1&()'(&<4+14$&<+$*,1$0(& ".&()$,+&":0&8$0("+,0%&()$*$&2"40%& Q,(5)& W'0,$#*& 8'9$*& NB[?6S\\& ,0& 3#'2$+*; ()$& 5'#$01'+& 2$'+;& M$+$P*& )":& W'0/ <4+14$& )$'1& .""(7'##& 5"'5)& =$..& ,$#*P&*'#'+2&5"83'+$*&("&"()$+&40,-$+/ >+")8& 8'2& 0$$1& ("& (),09& '7"4(& *,(,$*&,0&()$&'+$'&'01&,0&()$&>,%&C$0; )":& )$& 3#'0*& ("& *3$01& ),*& ?@AB& C"& *('+(6& #$(P*& 5"83'+$& W'0,$#*P& *'#'+2&'.($+&8'9,0%&()$&1$5,*,"0&("& *'#'+2&.+"8&()$&3'*(&()+$$&2$'+*;&b0& +$8',0& '(& <4+14$;& C)$+$& :'*& '& #"(& ?@AK6&W'0,$#*&:'*&8'9,0%&'&+$3"+(/ ".& *3$54#'(,"0& ,0& D"-$87$+& ()'(& $1& NK[@6S\@6& ,0& ?@AU& W'0,$#*& 3'2& >+")8&8'2&)$'1&*"4()&("&),*&)"8$& +',*$1& ("& '& *(4+12& NJ?B6KU\& '01& ,0& *('($&".&E$0(45926&74(&)$&1$5,1$1&("& ?@AJ&)$&*':&'&N[J6B\\&+',*$&("&8'9$& *('2&,0&F$*(&G'.'2$(($; NJJU6[UB;&D":&()$&<4+14$&3+$*,1$0(& -

Team Sorting

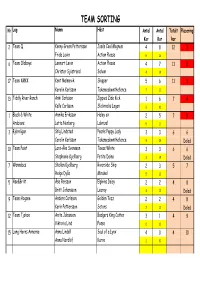

TEAM SORTING Nr Lag Namn Häst Antal Antal Totalt Placering Kor Kor kor 2 Team Q Kenny Green Pettersson Josés Cool Magnum 4 8 12 1 Frida Levin Action Please 816 6 Team Oldboys Lennart Levin Action Please 4 7 11 2 Christer Sjöstrand Salvan 414 17 Team KMKK Kent Malmevik Skipper 5 6 11 3 Karolin Karlsson Takemedownthefence 717 13 Tiddly River Ranch Anki Carlsson Zippies Zide Kick 1674 Kalle Carlsson Slickrocks Logan 610 1 Black & White Annika Eriksson Haley ox 2575 Arabians Lotta Norberg Lakrizal 511 3 Björnligan Stig Lindstad Pearls Peppy Lady 3366 Carolin Karlsson Takemedownthefence 915 Delad 10 Team Paint Lars-Åke Svensson Texas White 3366 Stephanie Kjellberg Petite Daina 314 Delad 7 Wannabes Stellan Kjellberg Riverside Skip 2357 Helge Dyås Mirakel 513 5 Åse&Britt Åse Persson Elphins Daisy 2248 Britt Johansson Leeroy 412 Delad 9 Team Hogane Anders Carlsson Golden Tezz 2248 Karin Pettersson Setors 213 Delad 12 Team Tjohoo Anita Johanson Badgers King Cutter 3149 Viktoria Lind Fosse 012 15 Long Horns Annorna Anna Lindell Soul of a Lynx 40410 Anna Nordlöf Kurre 210 TEAM SORTING 8 Sofia & Roses Michael Rumler Engla Rose 20211 Sofia Hökstrand Black Boy 119 16 Balls Or No Balls Jessica Hellstrand Mr Huckleberry Twist 10112 Carin Mogren Golds Daimler 118 4 Team Pretenders Peter Jonasson Enya 0000 Tina Jonasson Sparven 717 11 Team HC Ulf Owenede Mi Maxwell Smart 0000 Carina Grill Doubble Joe High Gear 615 14 Team Cowboy Lirarna Anders Johansson My Luzze Lad 0000 Dick Engdahl Raffy 311 RANCH TEAM SORTING Nr Lag Namn Häst Ko Nr Antal Tid för Placering -

FL HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 10:14 AM 12/11/2019 Page 1 29Th Annual Speedo Winter Championships - 12/12/2019 to 12/15/2019 Meet Program

Plantation Swim Team - FL HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 10:14 AM 12/11/2019 Page 1 29th Annual Speedo Winter Championships - 12/12/2019 to 12/15/2019 Meet Program Heat 2 of 2 Finals Event 1 Women 11-12 200 Yard Medley Relay 2 Midtown Weston A-FG B 2:23.17 _____ FGC Rec: 1:52.43 3/17/2018 Saint Andrew's Aquatics 3 Miami Country Da-FG A 2:20.99 _____ Aspen Gersper, Erin Miller, Breanna Wood, Kate Wis 4 Ransom Everglade-FG A 2:10.73 _____ FGC Open: 1:52.43 3/17/2018 Saint Andrew's Aquatics 5 Wahoo's of Welli-FG A 2:09.18 _____ Aspen Gersper, Erin Miller, Breanna Wood, Kate Wis 6 Metro Aquatic Cl-FG B 2:09.46 _____ Lane Team Relay Seed Time 7 Jupiter Dragons-FG A 2:11.37 _____ Heat 1 of 3 Finals 8 North Palm Beach-FG A 2:21.21 _____ 1 Gael Aquatic Clu-MR A 2:07.51 _____ 2 Blue Marlins Of-FG A 2:05.61 _____ Event 3 Women 13-14 200 Yard Medley Relay 3 Wahoo's of Welli-FG A 2:04.16 _____ FGC Rec: 1:46.55 3/16/2019 Pine Crest Swimming 4 Saint Andrew's A-FG A 2:02.46 _____ Julia Podkoscielny, Riley Botting, Lara Jones, Isa 5 Gulliver Swim Cl-FG A 1:58.84 _____ FGC Open: 1:46.55 3/16/2019 Pine Crest Swimming 6 Metro Aquatic Cl-FG A 2:01.74 _____ Julia Podkoscielny, Riley Botting, Lara Jones, Isa 7 North Palm Beach-FG A 2:03.70 _____ Lane Team Relay Seed Time 8 Midtown Weston A-FG A 2:04.28 _____ Heat 1 of 3 Finals 9 Pompano Beach Pi-FG A 2:07.40 _____ 1 North Palm Beach-FG A 1:58.46 _____ Heat 2 of 3 Finals 2 TS Aquatics-FG A 1:55.35 _____ 1 Saint Andrew's A-FG B 2:14.06 _____ 3 Saint Andrew's A-FG A 1:54.81 _____ 2 Metro Aquatic Cl-FG B 2:13.18 _____