The Theology and Practice of Sharing Ministry with Those in Need

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Origen De La Enfermería En El Cine: El Género Histórico-Documental Y Biográfico

ORIGEN DE LA ENFERMERÍA EN EL CINE: EL GÉNERO HISTÓRICO- DOCUMENTAL Y BIOGRÁFICO José Siles González Universidad de Alicante INTRODUCCIÓN El cine y las películas constituyen una herramienta fundamental para transmitir los fe- nómenos humanos en toda su complejidad, sin renunciar a ninguna de las dimensiones que intervienen en los acontecimientos. Ya Terencio y Shakespeare formularon la famosa frase: «Nada de lo humano me es ajeno». La enfermedad, el dolor, la muerte forman parte de la na- turaleza humana y, más tarde o temprano, de una u otro forma, acaban arribando a la existen- cia de todos los seres humanos que experimentan sus vivencias de forma tan diversa como compleja; es decir, mediante un determinado tipo de estética experiencial. Al cine, nada de lo humano le es ajeno y, particularmente, aquellos fenómenos vinculados a situaciones que producen cambios notables en quienes las viven (enfermedades, dolencias, pérdidas, etc.). Carper (1999) incluyó la dimensión estética como la cuarta integrante de los cuatro niveles del conocimiento enfermero (empírico-científico, ético, personal y estético). Otros autores desarrollaron modelos basándose en estos diferentes patrones y reinterpretando el conoci- miento estético desde las necesidades tanto del paciente como de la práctica profesional de enfermería partiendo de la base de la pertinencia de la estética ante situaciones –como el sufrimiento ante la enfermedad– donde el pensamiento subjetivo adquiere una gran intensi- dad (Chinn, 1994). Debido a su potencial de configuración ideológica (Lebel, 1973), el cine ha desempeña- do un papel determinante en el desarrollo de clichés, estereotipos y en una amplia gama de modelado de todos aquellos asuntos que forman parte de la realidad histórica. -

Aafa Action #6

AAFA ACTION The Official Publication of the Alford American Family Association September 1989 Vol. II, No.2 I .. .President's Precept. I HELLO KINFOLKS! TIllS IS THE CAPTAIN SPEAKING! WELCOME ABOARD! for all new members since our June newsletter. You're just in time to make your plans, make your reservations, and pack your bags for Houston. The countdown continues to the Second Annual Meeting of our Alford American Family Association to be held on October 14, 1989, in that fabu lous Texas city. But come early- our Texas spies led by D.L. Alford, Jr., have planned a Captain Lodwick H. Alford bodacious "get-acquainted" U.S. Navy, Retired· soiree for 6 p.m. on Friday, Oct. MFA PresidenJ 13. There)llill be light finger fvoo and a cash bar. If you've ever wondered whether other lines of Alfords were as peculiar and cantankerous as your own line, here is your chance to find out. Elsewhere in this newsletter is additional information about the meeting. Seriously now folks, HELP! Our superb Executive Assistant Gil Alford tells me the response to our recent questionnnaires was very disappointing. Only a small percentage of the forms was returned. Cousins, that just won't cut it. We've gOlIO have help if we expect to carry out the purposes of the Association, which are primarily to find answers to the questions and mysteries about our ancestors. I know you aren't afraid of work, but perhaps you don't want to get overloaded. I can understand that-let me assure you that we will not do that. -

Walking List CLERMONT (.ICO) MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:10/24/2017

Walking List CLERMONT (.ICO) MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:10/24/2017 SELECTION CRITERIA : ({voter.status} in ['A','I','P']) and {district.District_id} in [112] 530 CLARKE, SARAH E NP MD-A - MILFORD CITY A 530 CURTIS, DOUGLAS L REP BELT AVE MILFORD 45150 530 PATE, KAITLYN NICOLE NOPTY 531 WEDDING, LINDA K REP 502 KISSINGER, BETHANY A NOPTY 531 WEDDING, STEVEN P REP 502 KLOEPPEL, CODY ALAN NOPTY 535 HOWELL, JANET L REP 505 BOULARES, TARAK B NOPTY 535 HOWELL, STACY LYNN NOPTY 505 HOLSER, JOHN PERRY NOPTY 535 HOWELL, STEPHEN L REP 506 SHAFER, ETHAN REP 538 BREWER, KENNETH L NOPTY 506 SHAFER, JENNIFER M REP 538 BREWER, TAYLOR LANE NOPTY 508 BUIS, DEBBIE S REP 538 HALLBERG, KIMBERLY KAY REP 509 KOHAKE, DAVID S REP 539 HOYE, SARAH ELIZABETH DEM 509 KOHAKE, JACQUELINE REP 539 HOYE, STEPHEN MICHAEL NOPTY 510 GRAMSE, SARAH M DEM 542 #APT 3 MASON, LAURA J REP 510 ROA, JOYCE A DEM 542 #APT 3 MASON, ROBERT G REP 513 MARSH JR, RICHARD A NOPTY 542 #APT 4 ANDERSON, MARIE DOLORES M NOPTY 513 TETER, DIANE CHRISTINE NOPTY 542 #APT 4 LANIER, JEFFREY W REP 514 AKERS, TONIE R NOPTY 543 WOLBERS, ELENOR M REP 518 SMITH, DAVID SCOTT NOPTY 546 FIELDS, DEBORAH J NOPTY 518 SMITH, TAMARA JOY NOPTY 550 MULLEN, HEATHER L NOPTY 521 MCBEATH, COURTTANY ALENE REP 550 MULLEN, MICHAEL F DEM 522 DUNHAM, LINDSAY JO NOPTY 554 AUFDENKAMPE, JOHN G REP 522 DUNHAM CLARK, WILMA LOUISE NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, EDWIN L REP CHATEAU PL MILFORD 45150 525 HACKMEISTER, JUDY A DEM 526 SPIEGEL, JILL D DEM 2 #APT 2 SCHIRMER, CINDY S REP 526 SPIEGEL, LAWRENCE B DEM 2 #APT 3 CALLIS, SOMMER S -

True, False, and Neither 1-.1---1—LUU I

SOUTH BEND PUB-IC .118RARY. 304 S.MAIN ST., CITY. Hji */>. •'/ Prophecies Are Three Kind; True, False, and Neither 1-.1---1—LUU I... S What of Tomorrow? IRROR FRIDAY, JANUARY 16th, 1942 Know Your Bridge, but Don't Cross Until There HILE it is necessary that we keep our eye on the road, well as foot on the accelerator ELIEVE It and hand on the steering-wheel, as we drive through this war program, to execute a vic W torious finish, it isn't necessary that we empty the back of our heads entirely to the ! processes through which we are passing, or what we may find when we come back. The pessimist, Or ELSEl however, needs be optimistic of his. pessimism,—and the optimist needs some pessimism. It isn't the tire trouble that we MEAT O' THE COCONUT are having, the taxes we must pay, or the rationings through B$ Silas Witherspoon which we must pass, that is the big probem of civilian morale. It is the sense of the hereafter; Addenda to what about the morrow? Henry TYPHUS AND LICE "the infantry W. Wallace, vice president per of the snow force of Franklin D. Roosevelt, AID "INFANTRY OF and the cav president, tells us in Atlantic alry of the Monthly, the kind of peace we wild blast" SNOW AND CAVALRY must insist upon. His insistence that as allies is all well and good. OF WILD BLAST" IN of Alexander (On Page Three) DEFENDING MOSCOW ST. 1 gions like winter's withered leaves," the God of Battles, despite Stalin's reputed atheism, appears this time to so disdain Adolf Hitler's "hell bent" for Moscow, as to confront him also with a lutewaife of typhus and pincers of lice. -

OMGS Quarterly Surname Index

OMGS Quarterly Surname Index – M – Surname Given Name Volume Issue Pages Maben John 16 3 9 Maben Mary 16 3 9 Mabin Col. 16 1 10 Mabin Robert, Capt. 16 1 5, 9 Mabry J. P. 21 3 32 Mabry Joseph 25 3 29 Mabry Julia 8 3 104 MacAdam -- 20 2 29 MacAdam John Loudon 20 2 29 MacAllister -- 20 2 29, 30 MacAskill -- 4 2 79 Macaulay William A., Rev. 11 2 18 Macay John 19 4 13 MacCathay -- 20 2 31 MacCay -- 20 2 32 MacClean William 22 2 31 Macconaughay Joseph 29 1 23 MacConnel -- 20 2 35 MacConnell -- 20 2 30 MacCoy -- 20 2 35 MacCuaig -- 20 2 32 MacCug -- 20 2 32 MacCutcheon -- 20 2 30 Macdole James 20 1 17, 22 MacDonald -- 20 2 30 MacDonald Donald F. 20 2 1, 2, 29 MacDonald Flora 10 3 29 MacDowell Dorothy Kelly 19 3 17 MacEachern -- 20 2 30 MacFadyen Miriam 12 1 37 Macfarlan Janet 12 1 18, 19 MacGavie -- 20 2 32 MacGrath -- 20 2 36 Page 1 of 316 (C) Copyright OMGS 2011 OMGS Quarterly Surname Index – M – MacGraw -- 20 2 36 Macgruder Col. 2 3 129, 130, 131, 132 Macgruder J. B., Gen. 3 3 129 Machado Nancy Rice 13 3 24 Machan Archibald 25 2 16 Machan Henry 25 2 16 Machan Robert 25 2 16 Machen -- 3 4 165 Machen John 25 2 16 Machentire William 19 4 13 MacKay -- 20 2 35 Mackay Catherine 25 3 19 MacKean -- 20 2 33 MacKee -- 14 2 30 Mackelvey Wm. -

Genealogy of the Doremus Family in America

GENEALOGY — —OF THE DOREMUS FAMILY IN AMERICA: Descendants of Coknelis Doremus, from Breskens and mlddleburg, in holland, who emigrated to amer- ica about 1685-6,and shtl'i.kt) at acquacka- nonk (now Paterson), New Jersey. WILLIAMNELSON. PATERSON, N.L: THE PRESS PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY. 1897. Doremus Genealogy ifzA-y y-ViAAx) x GENEALOGY — — OF THE DOREMUS FAMILY IN AMERICA : Descendants of Cornelis. Doremus, from Breskens and . mlddelburg, in holland, whoemigrated to amer- ica about 1685-6, and settled at acquacka- nonk (now Paterson), New Jkrsey. WILLIAM NELSON. PATERSON, N. J. : TTIE PRESS PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY. c^1 y < One Hundred, Copies Printed. / & <>v TO MY WIFE SALOME WILLIAMSDOREMUS NELSON THIS RECORD OFHER ANCESTRY' AND KINSFOLK IS DEDICATED. FOREWORDS. Gj'HE material for the history of the Doremus Family for y;the first four or five generations, as given in the follow- oat}\i*Tf»A ' mo r»acr#»c Vine ViA#»n liv frit**writer nlmnct *»V- ing pages, has been gathered by the writer almost ex- clusively from original investigations in church registers, records of deeds and wills, and from tombstones. For the accounts of the later generations, and particularly of those scattered far from their ancestral homes, he has had to rely largely upon correspondence, often dilatory and otherwise unsatisfactory, but in very many cases prompt, intelligent and interested. It would be a pleasure, did not delicacy forbid, to mention some of those who have cordially re- sponded to the author's requests for information, and who have thus materially aided inmaking this little work more complete. -

Evangelical Friend, December 1982 /January 1983 (Vol

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Evangelical Friend (Quakers) 1-1983 Evangelical Friend, December 1982 /January 1983 (Vol. 16, No. 4/ 5) Evangelical Friends Alliance Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_evangelical_friend Recommended Citation Evangelical Friends Alliance, "Evangelical Friend, December 1982 /January 1983 (Vol. 16, No. 4/5)" (1983). Evangelical Friend. 161. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_evangelical_friend/161 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Evangelical Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. December 1982/ January 1983 • • • • •• • • t' • His name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace. (Continued on page 3) 2 EVANGELICAL FRIEND Senator Mark Hatfield is a controversial person. His clear Christian testimony and political positions seem to be in conflict for A one of two groups: 1. those who view political issues more conservatively, and 2. those who view Christianity more liberally. Featured in the October 22 issue of BEnER Christianity Today, Mark Hatfield describes his spiritual pilgrimage from a "disdainful attitude toward fundamentalists." "Finally," he says, "/reached a point where I had WAY to make some kind of commitment to Jesus Christ as Lord and Master as well as Redeemer. That commitment was my real encounter with Christ.'' His alternative to Christian organizations who take positions, disseminate literature and propound the Christian position on government and national policies is: "the living presence of Christ in the life of the believer in every facet of society. -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019 -

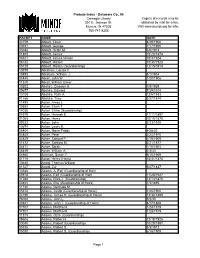

Probate Index - Delaware Co., in Carnegie Library Copies of Records May Be 301 E

Probate Index - Delaware Co., IN Carnegie Library Copies of records may be 301 E. Jackson St. obtained by mail for a fee. Muncie, IN 47305 Visit www.munpl.org for info. 765-747-8208 PACKET NAME DATE 04759 Abbott, Elmer 8/29/1908 03931 Abbott, George 1/17/1900 05684 Abbott, Hettie M. 5/6/1913 01805 Abbott, James 10/20/1874 08521 Abbott, James Vinson 10/3/1924 08132 Abbott, Marion 10/30/1923 05729 Abbott, Marion (Guardianship) 12/15/1914 10979 Abraham, Louisa C. 10495 Abraham, William J. 8/1/1934 04445 Abrell, John W. 1/20/1906 11510 Abrell, William Elmer 10202 Abshire, Dawson A. 3/8/1929 05677 Abshire, Edward 7/29/1914 10109 Abshire, Ruth A. 12/6/1933 01165 Abshire, Tirey 3/27/1874 11495 Acker, Amos L. 10852 Acker, Elijah T. 14038 Acker, Elvira (Guardianship) 04578 Acker, Hannah E. 11/11/1897 01065 Acker, Henry 10/15/1870 09322 Acker, John 2/23/1926 13674 Acker, Lewis H. 06404 Acker, Maria Priddy 4/28/33 04845 Acker, Peter 3/24/1910 04829 Acker, Samuel P. 3/19/1909 01672 Acker, Sanford M. 2/21/1877 04471 Acker, Sarah 1/10/1905 06459 Acker, William A. 2/3/33 04960 Ackman, Susan F. 9/10/1909 01716 Ackor, Henry (Heirs) 10/31/1870 13648 Acord, Thomas Willard 01527 Acord, Zur 9/27/1837 13546 Adams, A. Earl (Guardianship of Heir) 05918 Adams, Earl (Guardianship of Heir) 11/28/1927 01288 Adams, Eliza J. (Guardianship) 12/13/1870 03465 Adams, Ella (Guardianship of Heirs) 7/5/1895 11740 Adams, Gertrude M. -

Inscriptions and Graves Niagara Peninsula

"Ducit Amor Patriae" INSCRIPTIONS AND GRAVES IN THE NIAGARA PENINSULA JANET CARNOCHAN NIAGARA HISTORICAL SOCIETY RE-PRINT OF NUMBER 19 WITH ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS PRICE 60 CENTS THE NIAGARA ADVANCE PRINT, NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE FOREWARD In response to many requests for this popular publications, which was the outcome of many toilsome journeys, and much research on the part of the late Miss Janet Carnochan, the Society at length presents it with corrections and additions in the hope that it will be more valued than ever. Note: No. 19 is a Reprint of No. 10 with Additions and Corrections. PREFACE In studying the history of Niagara and vicinity the graveyards have been found a fruitful source of information, and over fifty of these have been personally visited. The original plan was to copy records of early settlers, United Empire Loyalists, Military or Naval Heroes, or those who have helped forward the progress of the country as Clergy, Teachers, Legislators, Agriculturists, etc., besides this, any odd or quaint inscriptions. No doubt many interesting and important inscriptions have been omitted, but the limits of our usual publication have already been far exceeded and these remain for another hand to gather. To follow the original lettering was desired, but the additional cost would have been beyond our modest means. Hearty thanks are here returned for help given by Col. Cruikshank, Rev. Canon Bull, Dr. McCollum, Mr. George Shaw, Rev. A. Sherk, Miss Forbes, Miss Shaw and Miss Brown, who all sent inscriptions from their own vicinity. It is hoped that the index of nearly six hundred names will be found of use and that our tenth publication will receive as kind a welcome as have the other pamphlets sent out by our Society. -

WVU Commencement Program

I42ND COMMENCEMENT WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY 1 ALMA MATER Alma, our Alma Mater, The home of Mountaineers. Sing we of thy honor, Everlasting through the years. Alma, our Alma Mater, We pledge in song to you. Hail, all hail, our Alma Mater, West Virginia “U.” —Louis Corson 2 Dear Graduates: Congratulations! You have worked hard to reach this day – the day you become a graduate of West Virginia University. Your hard work, perseverance, and enthusiasm for learning helped to get you to this point. With these qualities and the knowledge and skills acquired at WVU, you can achieve great things. To families and friends who are with us today to celebrate – thank you! You have played a critical role in helping students succeed in college, and you share credit for helping our students reach this monumental point in their lives. Graduates, you now belong to our worldwide alumni family of 175,000. Please stay in touch with us, and wear your flying WV with pride wherever your dreams may take you. Please visit us often. You always have a home here at WVU – where we are united in Mountaineer spirit. Best wishes for continued success. We are proud to call you one of our own. Let’s Go Mountaineers! James P. Clements, Ph.D. President West Virginia University 3 Dear Graduates: Congratulations on your graduation – you are now officially a member of the alumni family. Our more than 175,000 graduates proudly represent their alma mater in various professions, including science, business, sports, education, and performing arts to name a few. -

The Maine Genealogist

The Maine Genealogist February 2015 Volume 37, Number 1 The Maine Genealogical Society P.O. Box 2602, Waterville ME 04903 http://maineroots.org/ ELECTED OFFICERS FOR THE YEAR 2015 President Helen A. Shaw, CG Rockport, Maine Vice President Brian Bouchard Brunswick, Maine Treasurer Clyde G. Berry Winslow, Maine Membership Secretary Deborah Nowers Belfast, Maine Newsletter Editor Marlene A. Groves Rockland, Maine Program Chair Paul Doucette Gorham, Maine Recording Secretary Ann M. Durgin Blue Hill, Maine Research/Inquiries Secretary Pam J. Cote Scarborough, Maine Webmaster Brian Bouchard Brunswick, Maine Publications Sales Manager Roland Rhoades Gorham, Maine DIRECTORS Term Expiring in Jane Macomber Blanchard Twp., Maine December 2015 Roxanne Moore Saucier Bangor, Maine Term Expiring in Alfred T. Banfield, Jr. Bangor, Maine December 2016 Emily A. Schroeder South China, Maine Term Expiring in Marlene A. Groves Rockland, Maine December 2017 Carol McCoy Brunswick, Maine The Maine Genealogist Editor Joseph C. Anderson II, FASG Dallas, Texas Contributing Editors Michael F. Dwyer, FASG Pittsford, Vt. Priscilla Eaton, CG Rochester, N.Y. Patricia Law Hatcher, FASG, FGSP Dallas, Texas Leslie D. Sanders Marblehead, Mass. The Maine Genealogist (ISSN: 1064-6086) is published in February, May, August, and November. It is printed by Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine. See back page for membership rates and submission guidelines. For back issues, contact MGS’s Sales Manager at <[email protected]>. The Maine Genealogist Journal of the Maine Genealogical Society February 2015 Vol. 37, No. 1 CONTENTS PAGE EDITOR’S PAGE 2 CLARK DREW OF MAINE AND VERMONT Carole Gardner 3 A TIDBIT FROM THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES Lucretia Larrabee, First Wife of John Owen (d.