Magazin Jazzfest Berlin 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Jazzlondonlive Mar 2019

01/03/2019 SOUTH HILL PARK, BRACKNELL 19:30 £12 Greg Davis, sax, Cliff Charles, gtr, Paul Eldridge, ALINA BZHEZHINSKA'S HIPHARP COLLECTIVE JAZZ pno, Julian Bury, bass, Matt Skeaping, drms (£5.50 UNDER 18S) JAZZLONDONLIVE MAR 2019 CLUB CONCERT LULUK PURWANTO - VIOLIN & BYRON WALLEN - Award winning harpist Alina Bzhezhinska brings 02/03/2019 VORTEX JAZZ CLUB, DALSTON 20:30 £15.00 her latest project brings to life with the finest 01/03/2019 THE HAWTH, CRAWLEY 11:45 £21.95 (INCL TRUMPET PRESENTED BY BRACKNELL JAZZ compositions of legendary harpists Dorothy MONICA VASCONCELOS Simon Cook (piano), Andy Masters (bass), Dae Monica Vasconcelos (vcls), Steve Lodder (keys), LUNCH) Ashby and Alice Coltrane. Alina Bzhezhinska Hyun Lee (drums) (Harp), Gareth Lockrane (Flutes), Christian Ife Tolentino (gtr), Andres Lafone (bs), Yaron WHEN PEGGY MET ELLA PRESENTED BY THE Vaughan (Piano/Keyboards), Julie Walkington Stavi (bs), Marius Rodrigues (drs) LISTENING ROOM 01/03/2019 BARBICAN, EC2 20:00 £15-35 (Double Bass), Joel Prime (Drums) Shireen Francis (vcls), Sarah Moule (vcls), Simon THE BRANFORD MARSALIS QUARTET + NIKKI YEOH 02/03/2019 PIZZAEXPRESS JAZZ CLUB, SOHO 21:00 Wallace (pno) 01/03/2019 ARCHDUKE, WATERLOO 22:00 FREE £20 (SOLO SET) with Joey Calderazzo, Eric Revis & Justin SIMON PURCELL TRIO PIANO-LED JAZZ TRIO JAMES MORTON 'GROOVE DEN' 01/03/2019 SOUTHBANK CENTRE 13:00 FREE Faulkner MISHA LUNCHTIME FOYER GIG 01/03/2019 JAZZ CAFE, CAMDEN 22:30 £15 02/03/2019 606 CLUB, CHELSEA 21:30 £14.00 Intricate yet intuitive jazz from lauded bass player 01/03/2019 -

Island Sun News Sanibel Captiva

Read Us Online at IslandSunNews.com NEWSPAPER VOL. 20, NO. 31 SANIBELSanibel & CAPTIVA & Captiva ISLANDS, Islands FLORIDA JANUARY 25, 2013 JANUARY SUNRISE/SUNSET: 25 7:16 • 6:05 26 7:16 • 6:06 27 7:15 • 6:07 28 7:15 • 6:08 29 7:15 • 6:08 30 7:14 • 6:09 31 7:14 • 6:10 Quiz show competitors, from left, Caitlin Ross, Tyler Ulrich and Ashley Thibaut Center 4 Life, Sanibel School Gather For Potluck And Quiz Show by Jeff Lysiak Guests at the Historical Village’s fundraiser will have a chance to bid on lunch and a tour of Sanibel Fire Station #1. Pictured from left are Gerri Perkins of the auction committee, fire- hat was the smallest of Christopher Columbus’ three ships? fighter Shane Grant, Anita Smith of the auction committee and firefighter Brian Howell. How many teaspoons are in two tablespoons? W In which direction does the Earth spin – clockwise or counter-clockwise? If you’re like most folks, the answers to these questions may come to you after a Historical Village Live Auction Items little bit of thought or even some calculated guessing. However, for the three students – Caitlin Ross, Tyler Ulrich and Ashley Thibaut – participating in last Thursday’s Are You ive auction items at the Sanibel Historical Museum and Village’s February 5 Smarter Than A Fifth Grader? quiz show, the answers appeared to be rather easy. fundraiser, It’s Paradise ... Because, are varied enough to be on everyone’s wish But don’t blame John Brown, host of the Center 4 Life’s potluck/game night, who Llist, and exciting enough to entertain everyone. -

Annual Directory of Managers & Booking Agents

Annual Directory of Managers & Booking Agents Music-makersUpdated for tap 2021, into MC’sthis directory exclusive, to connectnational listwith of indie professionals labels, marketing will help &connect promo expertsyou to those and indiewho canpublicists. handle Plus your loads career of interestscontact informationand to arrange aid you live in promoting bookings. your(For musicMC’s list career, of Music DIY style:Attorneys, T-shirt please and CD visit development, musicconnection.com/industry-contacts.) blog sites and social media tools. MANAGERS Web: pedrogiraudo.com 1300 Clinton St., Ste 205 BRILLIANT PRODUCTIONS Styles: Argentine tango Nashville, TN 37203 Decatur, GA 30030 5B ARTIST MANAGEMENT Client: Pedro Giraudo Tango Quartet 404-312-6237 220 36th St., Ste. B442 BIG HASSLE MANAGEMENT Email: [email protected] Brooklyn, NY 11232 THE BABBLE BOUTIQUE 40 Exchange Place, Ste. 1900 Web: brilliant-productions.com 310-450-2555 Email: [email protected] New York, NY 10005 Contact: Nancy Lewis-Pegel Email: [email protected] Web: azaleemaslow.com/the-babble- 212-619-1360 Styles: roots, rock, jam, Americana, Web: 5bam.com boutique Web: bighassle.com/publicity blues Styles: Metal, Rock, Alt. Contact: Azalee Maslow Styles: alt., indie, rock, pop Clients: Webb Wilder, Geoff Achison, *No unsolicited material Styles: All Clients: A Girl Called Eddy, Adult Yonrico Scott, Randall Bramblett, Peter Services: Social and digital media Books, AFI, Alexandra Savior, Alice Karp, Glenn Phillips/Cindy Wilson of Additional location: consulting and management agency. Phoebe Lou, Alt-3, Chole Tang, Chrissie B-52’s We specialize in converting your Hynde, Charlie Burg, etc. (see website Services: A boutique agency that gives 12021 W. -

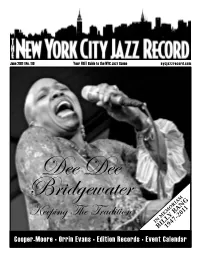

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

View Artists and Present the London Jazz and Theatre Scene

FILOMENA CAMPUS BA, MA Email [email protected] Website www.filomenacampus.me @FilomenaCampus <img width="510" height="638" alt="Filomena Campus" typeof="foaf:Image" class="img u-w- full" decoding="async"/> PROFILE Project title LIBERATE RAME. A revival of the creative and political labour of the actress, activist and ultimate theatre- maker Franca Rame. Supervisors Dr Tom Cornford and Dr Diana Damian Martin Profile I am a PhD Candidate at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, a visiting lecturer, a theatre director and jazz musician. My research focuses around the theatre work of Italian theatre practitioner Franca Rame, that I have known personally and who has influenced my work as a practitioner because of her revolutionary theatre and activist practice. My project aims to be a practical and theoretical feminist intervention on her work through the lens of intersectional critical thinking, in particular contemporary feminism and social reproduction theory. I am also interested in the way Rame and her partner Dario Fo used live music in their theatre and how they applied improvisation techniques in their theatre making. I have a BA (hons) in Foreign Languages and Literature (University of Cagliari), and an MA (Distinction) in Theatre Directing and Theatre Arts from Goldsmiths College, University of London. Since 2003 I have been working as a visiting lecturer and freelance director in UK universities such as the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, East15 Acting School, University of Essex, Kingston University, Bucks New University, and UCL. In my work as an educator and facilitator, I teach variously on theatre directing, acting, devising and physical theatre, improvisation techniques, voice, and contextual studies. -

Offentlig Journal

Norsk kulturråd 23.08.2013 Offentlig journal Periode: 20-08-2013 - 22-08-2013 Journalenhet: Alle Avdeling: Alle Saksbehandler: Alle Notater (X): Nei Notater (N): Nei Norsk kulturråd 23.08.2013 Offentlig journal Periode: 20-08-2013 - 06/01675-13 U Dok.dato: 24.07.2013 Jour.dato: 22.08.2013 Arkivdel: PERS Arkivkode: 221 Tilg. kode: UO Par.: Offl §13, fvl §13 Mottaker: Avskjermet Sak: Personalmappe - Avskjermet Dok: Refusjon av sykepenger Saksansv: Personal / BS Saksbeh: Personal / HMHA 08/00033-17 U Dok.dato: 17.06.2013 Jour.dato: 20.08.2013 Arkivdel: ADM Arkivkode: 046.9 Tilg. kode: U Par.: Mottaker: 'Kamilla Lundsæther' Sak: Medieovervåking Dok: Utvide Kulturrådets kontrakt Saksansv: Norsk kulturråd / JSD Saksbeh: Kommunikasjon / MAJ 08/03598-12 U Dok.dato: 16.08.2013 Jour.dato: 22.08.2013 Arkivdel: PNKR Arkivkode: 321\Musikktiltak Tilg. kode: U Par.: Mottaker: Tor Johan Bøen Sak: Restaurering av notemateriale fra Geir Tveitts kammermusikk Dok: Utbetaling 2. del - Restaurering av notemateriale fra Geir Tveitts kammermusikk Saksansv: Musikk / HLN Saksbeh: Musikk / RSH Side1 Norsk kulturråd 23.08.2013 Offentlig journal Periode: 20-08-2013 - 08/05726-7 I Dok.dato: 19.08.2013 Jour.dato: 20.08.2013 Arkivdel: PNKR Arkivkode: 321\Bestillingsverk Tilg. kode: U Par.: Avsender: Bergen Filharmoniske Orkester Sak: Asbjørn Schaathun - orkesterverk Dok: Utbetalingsanmodning - revisjonsberetning - Asbjørn Schaathun - orkesterverk Saksansv: Musikk / HLN Saksbeh: Musikk / HLN 09/00808-16 I Dok.dato: 21.08.2013 Jour.dato: 22.08.2013 Arkivdel: PNKR Arkivkode: 321\Fri scenekunst - teater Tilg. kode: U Par.: Avsender: Goksøyr & Martens - Toril Goksøyr Sak: Relevant realisme 4 produksjoner - 3-årig prosjekt Dok: Rapport for Foreldremøte - Relevant realisme 4 produksjoner - 3-årig prosjekt Saksansv: Scenekunst / MAST Saksbeh: Scenekunst / MAST 09/04246-15 I Dok.dato: 19.08.2013 Jour.dato: 21.08.2013 Arkivdel: PNKR Arkivkode: 321\Fri scenekunst - teater Tilg. -

Jall 20 Great Extended Play Titles Available in June

KD 9NoZ ! LO9O6 Ala ObL£ it sdV :rINH3tID AZNOW ZHN994YW LIL9 IOW/ £L6LI9000 Heavy 906 ZIDIOE**xx***>r****:= Metal r Follows page 48 VOLUME 99 NO. 18 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT May 2, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) Fla. Clerk Faces Obscenity Radio Wary of Indecent' Exposure Charge For Cassette Sale FCC Ruling Stirs Confusion April 20. She was charged with vio- BY CHRIS MORRIS lating a state statute prohibiting ington, D.C., and WYSP Philadel- given further details on what the LOS ANGELES A Florida retail "sale of harmful material to a per- BY KIM FREEMAN phia, where Howard Stern's morn- new guidelines are, so it's literally store clerk faces felony obscenity son under the age of 18," a third -de- NEW YORK Broadcasters are ex- ing show generated the complaints impossible for me to make a judg- charges for selling a cassette tape gree felony that carries a maximum pressing confusion and dismay fol- that appear to have prompted the ment on them as a broadcaster." of 2 Live Crew's "2 Live Crew Is penalty of five years in jail or a lowing the Federal Communications FCC's new guidelines. According to FCC general coun- What We Are" to a 14- year -old. As a $5,000 fine. Commission's decision to apply a "At this point, we haven't been (Continued on page 78) result of the case, the store has The arrest apparently stems from broad brush to existing rules defin- closed its doors. the explicit lyrics to "We Want ing and regulating the use of "inde- Laura Ragsdale, an 18- year -old Some Pussy," a track featured on cent" and /or "obscene" material on part-time clerk at Starship Records the album by Miami-based 2 Live the air. -

Sanibel Ano Captiva

WEEK OF JANUARY 18, 2012 is la n d REPORTER SANIBEL ANO CAPTIVA. FLORIDA VOLUME 51, NUMBER 12 1EI&hQE3IESSIIIIKSSS2SSIE33IIISSZ3QQZiISSSS23SSB3!i29I iff? The BAILEY- MATTHEWS MUSEUM Annual Museum Gala goes ‘Under the Sea’ January 27, 2013 at The Sanctuary Story on page 6. At the Library ................. 54 Classifieds ...................... 56 Living Sanibel................. 47 INSIDEf C a le n d a r............................. 8 Island Faces ....................50 Shell Shocked ................. 49 ODAY Captiva Current...............52 Island Reporter . .17-44 What’s Blooming .......... 47 ...214 Palm Lake Drive! SSMa03 jsuioisno lEijirapjseu Stroll to the Beach! 3/2.5 Sanibel Pool Home! ee/9# ijLujad www.214PalmLakeDrive.com Id ‘SU3AIAS Id $775,000 • Call Eric Pfeifer aivd aovisod sn 239-472-00 a is aisud Back to the roost at Ocean’s Reach Contributed to the ISLANDER "Our ‘Osprey Cam’ has been a huge hit "Life is for the birds" at Ocean’s Reach. with guests and friends of Ocean’s Reach," The resort’s unique "Osprey Cam" is giving said Andy Boyle, general manager. "We’ve vacationers a bird’s eye view of some of had dozens of people write us - some from their favorite feathered friends as they once as far away as the U.K., Scotland and again make their home here on Sanibel Finland - to remark how much they enjoy Island. logging on and watching the escapades of Osprey mate for life, and for the past five our resident osprey." years Ocean’s Reach has had a pair return to Ocean’s Reach is offering even more for the same spot at the resort - a special 35-foot birding enthuiasts. -

Newslist Drone Records 31. January 2009

DR-90: NOISE DREAMS MACHINA - IN / OUT (Spain; great electro- acoustic drones of high complexity ) DR-91: MOLJEBKA PVLSE - lvde dings (Sweden; mesmerizing magneto-drones from Swedens drone-star, so dense and impervious) DR-92: XABEC - Feuerstern (Germany; long planned, finally out: two wonderful new tracks by the prolific german artist, comes in cardboard-box with golden print / lettering!) DR-93: OVRO - Horizontal / Vertical (Finland; intense subconscious landscapes & surrealistic schizophrenia-drones by this female Finnish artist, the "wondergirl" of Finnish exp. music) DR-94: ARTEFACTUM - Sub Rosa (Poland; alchemistic beauty- drones, a record fill with sonic magic) DR-95: INFANT CYCLE - Secret Hidden Message (Canada; long-time active Canadian project with intelligently made hypnotic drone-circles) MUSIC for the INNER SECOND EDITIONS (price € 6.00) EXPANSION, EC-STASIS, ELEVATION ! DR-10: TAM QUAM TABULA RASA - Cotidie morimur (Italy; outerworlds brain-wave-music, monotonous and hypnotizing loops & Dear Droners! rhythms) This NEWSLIST offers you a SELECTION of our mailorder programme, DR-29: AMON – Aura (Italy; haunting & shimmering magique as with a clear focus on droney, atmospheric, ambient music. With this list coming from an ancient culture) you have the chance to know more about the highlights & interesting DR-34: TARKATAK - Skärva / Oroa (Germany; atmospheric drones newcomers. It's our wish to support this special kind of electronic and with a special touch from this newcomer from North-Germany) experimental music, as we think its much more than "just music", the DR-39: DUAL – Klanik / 4 tH (U.K.; mighty guitar drones & massive "Drone"-genre is a way to work with your own mind, perception, and sub bass undertones that evoke feelings of total transcendence and (un)-consciousness-processes. -

RNCM-Brochure-Summer-19-Web.Pdf

FS original What makes something original? Does originality actually exist or do we ԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖܥԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖԥ all simply build from what we have seen adjective and heard? adjective: original 1. What enables us to dare to be different not dependent on other people's ideas; inventive or novel. from others or independent of the context "a subtle and original thinker" in which we are working? What does the future of music look like? www.rncm.ac.uk/soundsoriginal 2 3 Wed 24 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall TRINITY CHURCH OF ENGLAND HIGH SCHOOL ANNIVERSARY CONCERT 2019 TWO FOR TUBULAR BELLS Tickets £5 Promoted by Trinity Church of England High School Sun 28 Apr // 7pm // RNCM Concert Hall OLDHAM CHORAL SOCIETY VERDI REQUIEM East Lancs Sinfonia Linda Richardson soprano Kathleen Wilkinson mezzo-soprano David Butt Philip tenor Thomas D Hopkinson bass Thu 02 – Sat 04 May // 7.30pm Nigel P Wilkinson conductor Sat 04 May // 2pm // RNCM Theatre Tickets £15 Promoted by Oldham Choral Society RNCM YOUNG COMPANY SWEET CHARITY Photo credit: Warren Kirby Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm Book by Neil Simon // Carole Nash Recital Room Music by Cy Coleman Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall Lyrics by Dorothy Fields ROSAMOND PRIZE Based on an original screenplay by Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaino TUBULAR BELLS FOR Produced for the Broadway stage by Fryer, Carr and Harris Conceived, Staged and Choreographed by Bob Fosse RNCM student composers collaborate with TWO Joseph Houston director Creative Writing students from Manchester Madeleine Healey associate director Metropolitan University to create new George Strickland musical director works in this annual prize. -

Basic Biography for Website TEMPLATE

Biography: Filomena Campus “Campus is a highly musical singer” The Telegraph Filomena Campus is a Sardinian jazz vocalist and lyricist, as well as a theatre director and producer. As a jazz vocalist Filomena has toured and collaborated with top UK jazz artists including Evan Parker, Guy Barker, Orphy Robinson, Huw Warren, Byron Wallen, Cleveland Watkiss, Jean Toussaint, Kenny Wheeler, the London Improvisers Orchestra and fellow Sardinian musicians Paolo Fresu and Antonello Salis. She has performed at several international jazz festivals in Edinburgh, Berlin, Croatia, Birmingham, Notting Hill, Manchester, Munich and Cagliari. In 2013 Filomena Campus launched her My Jazz Islands Festival, in which she seeks to unite her Sardinian roots with Italian and UK jazz musicians. The production Italy VS England, written by the Italian author Stefano Benni and with music by Steve Lodder and Dudley Philips, premiered at the festival in Cagliari and London in 2013 and will be revived in a new adaptation at this year's Theatralia Jazz Festival. Over the last three years Campus succeeded in presenting an impressive international line-up of jazz artists. In 2010 Filomena founded her own Filomena Campus Quartet with pianist Steve Lodder and Dudley Philips on double bass. Their Jester of Jazz project culminated in a recording in 2012 featuring the American saxophonist Jean Toussaint and British flautist Rowland Sutherland. Drummer Martin France joined the band in 2012. Together with Cleveland Watkiss, the winner of the 2010 London Jazz Award for best vocalist, Campus forms a vocal duo. Her most recent recording from 2014 is with guitarist Giorgio Serci: Scaramouche.