Bobcats/Trapper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Hunting Seasons

CHAPTER 9 BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOAT HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703, § 23-2-104 and § 23-3-117. Section 2. Definitions. In addition to the definitions set forth in Title 23 of the Wyoming Statutes and Chapter 2, General Hunting Regulation, the Commission also adopts the following definitions for the purpose of this chapter; (a) “Bighorn sheep horns” mean the hollow horn sheaths of male bighorn sheep, either attached to the skull or separated. (b) “Plugging” means placement of a permanent metal plug provided and attached by the Department. Section 3. Bighorn Sheep Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Hunt Archery Dates Season Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 12 Any ram 2 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 20 Any ram 3 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 32 Any ram 4 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 24 Any ram 5 1 Aug. 1 Aug. 31 32 Any sheep valid within the Owl Creek Drainage 5 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 Any ram valid in the entire area 6 1 Aug. 1 Aug. 14 Aug. 15 Oct. 31 1 Any ram (1 resident) 7 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 12 Any bighorn sheep 8 1 Aug. 15 Aug. 31 Sep. 1 Oct. 31 7 Any ram (5 residents, 2 nonresidents) 9 1 Aug. -

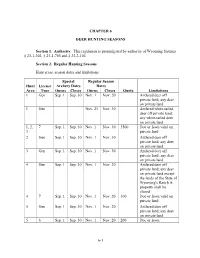

Wyoming Game & Fish Commission

Draft 3-22-2021.3 CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Hunt Archery Dates Season Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on private 3 3000 land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep. -

Deer Season Subject to the Species Limitation of Their License in the Hunt Area(S) Where Their License Is Valid As Specified in Section 2 of This Chapter

CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Season Hunt License Archery Dates Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on 3 private land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6-1 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep. -

Carbon County DRAFT Natural Resource Management Plan

FEBRUARY 16, 2021 Carbon County DRAFT Natural Resource Management Plan Natural Resource Management Plan Y2 Consultants, LLC & Falen Law Offices (Intentionally Left Blank) Natural Resource Management Plan Y2 Consultants, LLC & Falen Law Offices CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... III LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... VII LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... IX CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................10 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................10 1.2 STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................11 1.3 CARBON COUNTY NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN PROCESS ..............................................15 1.4 CREDIBLE DATA ....................................................................................................................19 CHAPTER 2: CUSTOM AND CULTURE ........................................................................................21 2.1 COUNTY INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ....................................................................................21 2.2 CULTURAL/HERITAGE/PALEONTOLOGICAL -

Wyoming Game and Fish Commission’S Wick Wildlife Habitat Management Area South of Interstate 80 Shall Be Closed

Draft 3-23-2021.3 CHAPTER 7 ELK HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Hunt Archery Dates Season Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 1 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Oct. 15 Nov. 30 100 Any elk 1 4 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Oct. 15 Nov. 30 75 Antlerless elk 2 1 Oct. 21 Nov. 1 60 Any elk 2 4 Sep. 18 Sep. 27 80 Antlerless elk 2 4 Oct. 21 Nov. 1 Antlerless elk 2 6 Sep. 18 Sep. 27 20 40 Cow or calf 2 6 Oct. 21 Nov. 1 Cow or calf 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 14 Sep. 15 Oct. 14 Any elk 3 Gen Oct. 15 Jan. 31 Any elk valid south of U.S. Highway 26 3 6 Aug. 15 Nov. 30 200 Cow or calf 3 6 Dec. 1 Jan. 31 Cow or calf valid south of U.S. Highway 26 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Oct. 1 Oct. 31 Any elk valid off national forest 6 Gen Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlerless elk valid off national forest 6 1 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Oct. 15 Oct. 31 75 Any elk 6 1 Nov. 1 Jan. 31 Antlerless elk 6 4 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Jan. 31 50 Antlerless elk Oct. 15 6 6 Aug. 15 Jan. 31 1100 Cow or calf valid off national forest 7 1 Sep. -

View Draft Regulation

Chapter 9, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Hunting Seasons At the time of this filing, the 2020 bighorn sheep and mountain goat harvest information is not yet available to the Department. Individual hunt area regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, license types and license quotas may be modified after harvest data has been evaluated. Any additional proposed changes to regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, numbers of limited quota licenses, license types, hunt area boundaries or modifications to other hunting provisions shall be made available for public comment on the Department website. An updated draft of 2021 bighorn sheep and mountain goat hunting season proposals will also be posted to the Department website during the later portion of the public comment period. Please scroll down to view the regulation or click the down arrow for the next page. Draft 12-10-2020.1 CHAPTER 9 BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOAT HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703, § 23-2-104 and § 23-3-117. Section 2. Definitions. In addition to the definitions set forth in Title 23 of the Wyoming Statutes and Chapter 2, General Hunting Regulation, the Commission also adopts the following definitions for the purpose of this chapter; (a) “Bighorn sheep horns” mean the hollow horn sheaths of male bighorn sheep, either attached to the skull or separated. (b) “Plugging” means placement of a permanent metal plug provided and attached by the Department. -

Roadless Area Evaluation

Appendix C MEDICINE BOW NATIONAL FOREST Revised Land and Resource Management Plan Final Environmental Impact Statement Roadless Area Evaluation Table of Contents ROADLESS AREAS....................................................................................................................... C-1 Background .............................................................................................................................C-1 CRITERIA .................................................................................................................................... C-2 Wilderness Capability:............................................................................................................C-3 Availability for Wilderness:....................................................................................................C-3 Need for Wilderness................................................................................................................C-4 INDIVIDUAL ROADLESS AREA ANALYSES: .............................................................................. C-11 R20601Strawberry Creek 5,876 Acres................................................................................ C-12 Capability..............................................................................................................................C-13 Availability: ..........................................................................................................................C-14 Need ......................................................................................................................................C-15 -

Chapter 7, Elk Hunting Seasons

Chapter 7, Elk Hunting Seasons At the time of this filing, the 2020 elk harvest information is not yet available to the Department. Individual hunt area regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, license types and license quotas may be modified after harvest data has been evaluated. Any additional proposed changes to regular hunting season dates, special archery hunting season dates, hunt area limitations, numbers of limited quota licenses, license types, hunt area boundaries or modifications to other hunting provisions shall be made available for public comment on the Department website. An updated draft of 2021 elk hunting season proposals will also be posted to the Department website during the later portion of the public comment period. Chapter 7, Elk Hunting Seasons. Elk hunt area 113 is proposed to be open for the 2021 hunting season. Elk hunt area 123 will not offer any Type 1 (any elk) licenses for the 2021 hunting season. These actions are intended to meet the management objectives of these elk hunt areas. Section 4, edits have been proposed to further clarify elk hunting season provisions for persons who qualify for and are in possession of hunting season extension permits. During the 2020 hunting season, special archery season information was repositioned within this regulation and caused some confusion among hunting season extension permit holders. The edited language in this Section is meant to clarify when a hunting season extension permit is valid. Section 8, elk hunt area 114 is being dissolved and the associated geographic area is being incorporated into adjoining hunt areas 10 and 11. -

Wyoming Game and Fish Commission

Draft 4-10-19.3 CHAPTER 4 FURBEARING ANIMAL HUNTING OR TRAPPING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statute § 23-1-302, § 23-2-303, § 23-2-304, § 23-2-305 and § 23-3-109. Section 2. Definitions. Definitions shall be as set forth in Title 23, Wyoming Statutes, Commission regulations, and the Commission also adopts the following definitions: (a) “Drainage” means all lands within the watershed of a named river or stream, including all tributaries and standing waters whichthat drain into that the named river or stream. (b) “Leg-hold Trap” means any device using a mechanical trigger that springs the jaws or loop shut for capturing furbearing or predatory animals. (c) “Live Trap” means any device designed to capture or trap a live animal inside a cage or structure. Such traps include, but are not limited to box traps and cage traps. (d) “Owner” means the person who physically sets any trap or snare in any fashion that may result in the take of any furbearing or predatory animal. (e) “Pet” means any domestic or tamed animal kept for companionship or pleasure. (f) “Quick-kill Body-grip Trap” means a device that closes around the body or head of the animal in such a manner as to almost immediately kill the animal caught. (g) “Raw Fur” means the untanned hide or skin, or the unskinned carcass of a furbearing animal. (h) “Snare” means a device consisting of a loop with no mechanical trigger for capturing furbearing or predatory animals. (j) “Tamper” means to disturb, obstruct, damage, steal or interfere with any legally placed trap or snare except for releasing any pet or livestock from a trap or snare. -

Section 5 I Southcentral Area Ncluding Including Casper, Riverton, Lander and Rawlins

SECTION 5 I SOUTHCENTRAL AREA NCLUDING INCLUDING CASPER, RIVERTON, LANDER AND RAWLINS post provided a link between East and West in C communications and supply transport. The Post ASPER at Platte Bridge, also known as Fort Clay, Camp S OUTHCENTRAL Davis, and Camp Payne, was associated with two , R significant military campaigns, the Sioux Expedition of 1855-1856 and the Utah IVERTON Expedition of 1858-1859. Furthermore, the mili- tary camp played an important role in Indian- Euro-American relations. , L A The post at Platte Bridge protected the most ANDER AND REA important river crossing in Wyoming, in the most hostile area of Wyoming, aiding in travel and communication on the Oregon Trail. Undoubtedly, the camp also played a significant role in relations between Plains Indian tribes and R the U S. Army as the post acted out it’s role as AWLINS peacekeeper, protector, and aggressor.” Memorial Cemetery and Mausoleum This site is located lust north of the Evansville Elementary School near the corner of 5th and Albany Streets on a tract of land known as the “Oregon Trail Memorial Park.” This is the burial tomb of six skeletons recovered from an unmarked cemetery believed to be circa 1850s. Research indicated that the initial remains consist- ed of four males and two females. Later three North of Rawlins skeletons, believed to be Native Americans, were included in the interment. Five of the skeletons, and Cheyenne hunted the buffalo. In addition is Food including one of the females, were clothed in mili- 1 the location of the “Mysterious Cross.” tary uniform, parts of which were recovered with Section 5 military buttons and insignia attached. -

Raw Water Supply Level Ii Report

This is a digital document from the collections of the Wyoming Water Resources Data System (WRDS) Library. For additional information about this document and the document conversion process, please contact WRDS at [email protected] and include the phrase “Digital Documents” in your subject heading. To view other documents please visit the WRDS Library online at: http://library.wrds.uwyo.edu Mailing Address: Water Resources Data System University of Wyoming, Dept 3943 1000 E University Avenue Laramie, WY 82071 Physical Address: Wyoming Hall, Room 249 University of Wyoming Laramie, WY 82071 Phone: (307) 766-6651 Fax: (307) 766-3785 Funding for WRDS and the creation of this electronic document was provided by the Wyoming Water Development Commission (http://wwdc.state.wy.us) BBBAAAGGGGGGSSS WWWAAATTTEEERRR &&& RRRAAAWWW WWWAAATTTEEERRR SSSUUUPPPPPPLLLYYY LLLEEEVVVEEELLL IIIIII RRREEEPPPOOORRRTTT BBBaaaggggggsss,,, WWWyyyooommmiiinnnggg BAGGS WATER & RAW WATER SUPPLY LEVEL II REPORT Prepared for: TOWN OF BAGGS P.O. Box 300 Baggs, WY 82321 WYOMING WATER DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 6290 Yellowtail Road Cheyenne, WY 82002 Prepared by: DONNELL & ALLRED, INC. 908 Big Horn Avenue Worland, WY 82401 In association with: LIDSTONE AND ASSOCIATES, INC. 4025 Automation Way, Bldg E Fort Collins, CO 80525 November 1,2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 History and Project Background..........................................................................