Whirlpools and Pinwheels on the Sky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Coast Astronomy Virtual Star Party May 15Th 7Pm Pacific

Central Coast Astronomy Virtual Star Party May 15th 7pm Pacific Welcome to our Virtual Star Gazing session! We’ll be focusing on objects you can see with binoculars or a small telescope, so after our session, you can simply walk outside, look up, and understand what you’re looking at. CCAS President Aurora Lipper and astronomer Kent Wallace will bring you a virtual “tour of the night sky” where you can discover, learn, and ask questions as we go along! All you need is an internet connection. You can use an iPad, laptop, computer or cell phone. When 7pm on Saturday night rolls around, click the link on our website to join our class. CentralCoastAstronomy.org/stargaze Before our session starts: Step 1: Download your free map of the night sky: SkyMaps.com They have it available for Northern and Southern hemispheres. Step 2: Print out this document and use it to take notes during our time on Saturday. This document highlights the objects we will focus on in our session together. Celestial Objects: Moon: The moon 4 days after new, which is excellent for star gazing! *Image credit: all astrophotography images are courtesy of NASA & ESO unless otherwise noted. All planetarium images are courtesy of Stellarium. Central Coast Astronomy CentralCoastAstronomy.org Page 1 Main Focus for the Session: 1. Canes Venatici (The Hunting Dogs) 2. Boötes (the Herdsman) 3. Coma Berenices (Hair of Berenice) 4. Virgo (the Virgin) Central Coast Astronomy CentralCoastAstronomy.org Page 2 Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs) Canes Venatici, The Hunting Dogs, a modern constellation created by Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in 1687. -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

The Local Galaxy Volume

11-1 How Far Away Is It – The Local Galaxy Volume The Local Galaxy Volume {Abstract – In this segment of our “How far away is it” video book, we cover the local galaxy volume compiled by the Spitzer Local Volume Legacy Survey team. The survey covered 258 galaxies within 36 million light years. We take a look at just a few of them including: Dwingeloo 1, NGC 4214, Centaurus A, NGC 5128 Jets, NGC 1569, majestic M81, Holmberg IX, M82, NGC 2976,the unusual Circinus, M83, NGC 2787, the Pinwheel Galaxy M101, the Sombrero Galaxy M104 including Spitzer’s infrared view, NGC 1512, the Whirlpool Galaxy M51, M74, M66, and M96. We end with a look at the tuning fork diagram created by Edwin Hubble with its description of spiral, elliptical, lenticular and irregular galaxies.} Introduction [Music: Johann Pachelbel – “Canon in D” – This is Pachelbel's most famous composition. It was written in the 1680s between the times of Galileo and Newton. The term 'canon' originates from the Greek kanon, which literally means "ruler" or "a measuring stick." In music, this refers to timing. In astronomy, "a measuring stick" refers to distance. We now proceed to galaxies more distant than the ones in our Local Group.] The Local volume is the set of galaxies covered in the Local Volume Legacy survey or LVL, for short, conducted by the Spitzer team. It is a complete sample of 258 galaxies within 36 million light years. This montage of images shows the ensemble of galaxies as observed by Spitzer. The galaxies are randomly arranged but their relative sizes are as they appear on the sky. -

Of Galaxies, Stars, Planets and People

The Cosmic Journeys of Galaxies,A Research Programme forStars, the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium Planets and People This document was produced by the staff of the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, in particular through discussions and contributions from the tenured astronomers, together with input from the Governors and the Management Committee. The document was edited by the Director, Michael Burton and designed by Aileen McKee. Produced in March 2017 Front Cover Images The Four Pillars of the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium Research Outreach The Armagh Observatory was founded in 1790 as The Armagh Planetarium was founded by Dr Eric part of Archbishop Richard Robinson’s vision to see Lindsay, the seventh director of the Observatory, as the creation of a University in the City of Armagh. part of his vision to communicate the excitement of It is the oldest scientific institution in Northern astronomy and science to the public. It opened on Ireland and the longest continuously operating the 1st of May, 1968 and is the oldest operating astronomical research institution in the UK and planetarium in the UK and Ireland. Ireland. History Heritage Dreyer's NGC – the New General Catalogue – was The Observatory has been measuring the weather published in 1888 by JLE Dreyer, fourth Director of conditions at 9am every day since 1794, a the Observatory. It has been used extensively by meteorological record covering more than 200 astronomers ever since. This is his annotated copy, years, believed to be longest standing in the British complete with all known corrections at the time. Isles. This image shows the sunshine recorder and Galaxies and nebulae are still often cited by their anemometer. -

Monthly Observer's Challenge

MONTHLY OBSERVER’S CHALLENGE Las Vegas Astronomical Society Compiled by: Roger Ivester, Boiling Springs, North Carolina & Fred Rayworth, Las Vegas, Nevada With special assistance from: Rob Lambert, Las Vegas, Nevada JUNE 2015 Introduction The purpose of the Observer’s Challenge is to encourage the pursuit of visual observing. It’s open to everyone that’s interested, and if you’re able to contribute notes, and/or drawings, we’ll be happy to include them in our monthly summary. We also accept digital imaging. Visual astronomy depends on what’s seen through the eyepiece. Not only does it satisfy an innate curiosity, but it allows the visual observer to discover the beauty and the wonderment of the night sky. Before photography, all observations depended on what the astronomer saw in the eyepiece, and how they recorded their observations. This was done through notes and drawings, and that’s the tradition we’re stressing in the Observers Challenge. We’re not excluding those with an interest in astrophotography, either. Your images and notes are just as welcome. The hope is that you’ll read through these reports and become inspired to take more time at the eyepiece, study each object, and look for those subtle details that you might never have noticed before. M83 – NGC-5236 The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy In Hydra M83, also known as NGC-5236, is a face-in barred spiral galaxy in the southern sky, which lies in the constellation of Hydra. Charles Messier added it to his catalogue of non-comets in March 1781, but it was actually discovered by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille on February 23, 1752 from his observatory in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. -

GALAXIES WHAT ARE the DEEP SKY OBJECTS? •Deep-Sky Objects Are Astronomical Objects Other Than Individual Stars and Solar System Objects (Sun, Moon, Planets, Comets)

GALAXIES WHAT ARE THE DEEP SKY OBJECTS? •Deep-sky objects are astronomical objects other than individual stars and solar system objects (Sun, Moon, planets, comets). TYPES OF DEEP SKY OBJECTS •Nebulae •Clusters •Galaxies CHARLES MESSIER • Known for the Messier catalogue of galaxies, nebulae and star clusters M1 to M110 • He was a French astronomer who lived in the 18th century. • He was a comet hunter and the purpose of the catalogue was to record the sky objects that looked as comets but were not comets because they would not move in the sky. UNITS TO MEASURE DISTANCE • A Light-year is the distance that light travels in a year with a speed of approximately 300,000 kilometers per second • Closest star to the Sun is Proxima Centauri at 4.37 light years. • A Parsec is the equal to about 3.26 light years GALAXIES • A galaxy is an enormous collection of gas, dust and billions of stars held together by gravity. One galaxy can have hundreds of billions of stars and be as large as 200,000 light years across. • Galaxy is derived from the Greek galaxias meaning "milky", a reference to the Milky Way. • Many galaxies are believed to have black holes at their active center. The Milky Way's central black hole, known as Sagittarius A, has a mass four million times that of our Sun. GALAXIES FACTS • There are potentially more than 170 billion galaxies in the observable universe. Some, called dwarf galaxies, are very small with about 10 million stars, while others are huge containing an estimated 100 trillion stars. -

Astronomy in the Park 2014 Schedule

Astronomy in the Park 2014 Schedule Members of the Stockton Astronomical Society will volunteer to setup their telescopes for the public at S.J. County Oak Grove Regional Park on the first Saturday after the New Moon. During the months of April through October the Nature Center will also be open with indoor astronomy activities. If the sky is cloudy or there is bad weather the telescopes may not be available. During the months of November through March the Nature Center will not be open. Also, if the sky is not clear the event may be canceled and we will try again the next month. • S.J. County charges a Parking Fee of $6.00 per vehicle but the Nature Center and telescope viewing is free. • SAS volunteers can contact James Rexroth for free parking passes. • Indoor astronomy themed activities for kids (both big & small) will be in the Nature Center. • Telescope viewing starts after Sunset, the Moon will be visible in the telescopes from the start. As the sky darkens more objects become visible. Darker and clearer sky is better for viewing. • Every month we will feature a different deep sky object. We will point one of our large telescopes at this object during the last hour of the evening. These objects are dim and fuzzy and are best seen in large aperture telescopes. • To view objects it may be necessary to stand on a ladder or step stool that will be next to the telescope. For more information call: James Rexroth S.J. County Oak Grove Regional Park (Nature Center) (209) 953-8814 Doug Christensen Stockton Astronomical Society (209) 462-0798 -

The Messier Catalog

The Messier Catalog Messier 1 Messier 2 Messier 3 Messier 4 Messier 5 Crab Nebula globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 6 Messier 7 Messier 8 Messier 9 Messier 10 open cluster open cluster Lagoon Nebula globular cluster globular cluster Butterfly Cluster Ptolemy's Cluster Messier 11 Messier 12 Messier 13 Messier 14 Messier 15 Wild Duck Cluster globular cluster Hercules glob luster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 16 Messier 17 Messier 18 Messier 19 Messier 20 Eagle Nebula The Omega, Swan, open cluster globular cluster Trifid Nebula or Horseshoe Nebula Messier 21 Messier 22 Messier 23 Messier 24 Messier 25 open cluster globular cluster open cluster Milky Way Patch open cluster Messier 26 Messier 27 Messier 28 Messier 29 Messier 30 open cluster Dumbbell Nebula globular cluster open cluster globular cluster Messier 31 Messier 32 Messier 33 Messier 34 Messier 35 Andromeda dwarf Andromeda Galaxy Triangulum Galaxy open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy Messier 36 Messier 37 Messier 38 Messier 39 Messier 40 open cluster open cluster open cluster open cluster double star Winecke 4 Messier 41 Messier 42/43 Messier 44 Messier 45 Messier 46 open cluster Orion Nebula Praesepe Pleiades open cluster Beehive Cluster Suburu Messier 47 Messier 48 Messier 49 Messier 50 Messier 51 open cluster open cluster elliptical galaxy open cluster Whirlpool Galaxy Messier 52 Messier 53 Messier 54 Messier 55 Messier 56 open cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster globular cluster Messier 57 Messier -

The Messier Marathon Search Sequence

2/28/2020 Messier Marathon Search Sequence List This file presents the Messier objects in the order of the Marathon Search Sequence given by Don Machholz in his Messier Marathon Observer's Guide. The Messier Marathon Search Sequence compiled online by Hartmut Frommert, using work of Don Machholz. Depending on geographic location, it may be impossible to find them all, and may be better to slightly modify this list. In case of doubt consult Don Machholz's book. This list should be good for northern latitudes 20 to 40. 1. M77 spiral galaxy in Cetus 2. M74 spiral galaxy in Pisces 3. M33 The Triangulum Galaxy (also Pinwheel) spiral galaxy in Triangulum 4. M31 The Andromeda Galaxy spiral galaxy in Andromeda 5. M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 6. M110 Satellite galaxy of M31 elliptical galaxy in Andromeda 7. M52 open cluster in Cassiopeia 8. M103 open cluster in Cassiopeia 9. M76 The Little Dumbell, Cork, or Butterfly planetary nebula in Perseus 10. M34 open cluster in Perseus 11. M45 Subaru, the Pleiades--the Seven Sisters open cluster in Taurus 12. M79 globular cluster in Lepus 13. M42 The Great Orion Nebula diffuse nebula in Orion 14. M43 part of the Orion Nebula (de Mairan's Nebula) diffuse nebula in Orion 15. M78 diffuse reflection nebula in Orion 16. M1 The Crab Nebula supernova remnant in Taurus 17. M35 open cluster in Gemini 18. M37 open cluster in Auriga 19. M36 open cluster in Auriga 20. M38 open cluster in Auriga 21. M41 open cluster in Canis Major 22. -

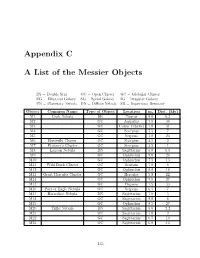

Appendix C a List of the Messier Objects

Appendix C A List of the Messier Objects DS=DoubleStar OC=OpenCluster GC=GlobularCluster EG = Elliptical Galaxy SG = Spiral Galaxy IG = Irregular Galaxy PN = Planetary Nebula DN = Diffuse Nebula SR = Supernova Remnant Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M1 Crab Nebula SR Taurus 9.0 6.3 M2 GC Aquarius 7.5 36 M3 GC Canes Venatici 7.0 31 M4 GC Scorpius 7.5 7 M5 GC Serpens 7.0 23 M6 Butterfly Cluster OC Scorpius 4.5 2 M7 Ptolemy’s Cluster OC Scorpius 3.5 1 M8 Lagoon Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 6.5 M9 GC Ophiuchus 9.0 26 M10 GC Ophiuchus 7.5 13 M11 Wild Duck Cluster OC Scutum 7.0 6 M12 GC Ophiuchus 8.0 18 M13 Great Hercules Cluster GC Hercules 5.8 22 M14 GC Ophiuchus 9.5 27 M15 GC Pegasus 7.5 33 M16 Part of Eagle Nebula OC Serpens 6.5 7 M17 Horseshoe Nebula DN Sagittarius 7.0 5 M18 OC Sagittarius 8.0 6 M19 GC Ophiuchus 8.5 27 M20 Trifid Nebula DN Sagittarius 5.0 2.2 M21 OC Sagittarius 7.0 3 M22 GC Sagittarius 6.5 10 M23 OC Sagittarius 6.0 4.5 135 Object Common Name Type of Object Location mv Dist. (kly) M24 Milky Way Patch Star cloud Sagittarius 11.5 10 M25 OC Sagittarius 4.9 2 M26 OC Scutum 9.5 5 M27 Dumbbell Nebula PN Vulpecula 7.5 1.25 M28 GC Sagittarius 8.5 18 M29 OC Cygnus 9.0 7.2 M30 GC Capricornus 8.5 25 M31 Andromeda Galaxy SG Andromeda 3.5 2500 M32 Satellite galaxy of M31 EG Andromeda 10.0 2900 M33 Triangulum Galaxy SG Triangulum 7.0 2590 M34 OC Perseus 6.0 1.4 M35 OC Gemini 5.5 2.8 M36 OC Auriga 6.5 4.1 M37 OC Auriga 6.0 4.6 M38 OC Auriga 7.0 4.2 M39 OC Cygnus 5.5 0.3 M40 Winnecke 4 DS Ursa Major 9.0 M41 OC Canis -

Messier Object Mapping System

Messier Object Mapping System Messier Object Constellation Map# Messier Object Constellation Map# M1 Taurus 1-6 M56 Lyra 3 M2 Aquarius 8 M57 Lyra 3 M3 Canes Venatici 4-10 M58 Virgo IN2-5 M4 Scorpius 2 M59 Virgo IN2 M5 Scorpius 10 M60 Virgo IN2-5-9-10 M6 Scorpius 2 M61 Virgo IN2-5-8 M7 Scorpius 2 M62 Ophiuchus 2 M8 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M63 Canes Venatici 4 M9 Ophiuchus 2 M64 Coma Berenices 4-5 M10 Ophiuchus 2 M65 Leo 5 M11 Scutum 2 M66 Leo 5 M12 Ophiuchus 2 M67 Cancer 6 M13 Hercules 3 M68 Hydra 9 M14 Ophiuchus 2 M69 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M15 Pegasus 8 M70 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M16 Serpens 2-IN1 M71 Sagittarius 2 M17 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M72 Aquarius 8 M18 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M73 Aquarius 8 M19 Ophiuchus 2 M74 Pisces 11 M20 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M75 Sagittarius 8 M21 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M76 Perseus 7 M22 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M77 Cetus 11 M23 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M78 Orion 1 M24 Sagittarius 2-IN1 M79 Lepus 1 M25 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M80 Scorpius 2 M26 Scutum 2 M81 Ursa Major 4 M27 Vupecula 3 M82 Ursa Major 4 M28 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M83 Hydra 9 M29 Cygnus 3 M84 Virgo IN2-5 M30 Capricornus 8 M85 Coma Berenices 4-5 M31 Andromeda 7-11 M86 Virgo IN2-5 M32 Andromeda 7-11 M87 Virgo IN2-5 M33 Triangulum 7-11 M88 Coma Berenices IN2-5 M34 Perseus 7-11 M89 Virgo IN2 M35 Gemini 1-6 M90 Virgo IN2-5 M36 Auriga 1-6 M91 Virgo IN2-5 M37 Auriga 1-6 M92 Hercules 3 M38 Auriga 1 M93 Puppis 1-6 M39 Cygnus 3-7 M94 Canes Venatici 4-5 M40 Ursa Major 4 M95 Leo 5 M41 Canis Major 1 M96 Leo 5 M42 Orion 1 M97 Ursa Major 4 M43 Orion 1 M98 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M44 Sagittarius 6 M99 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M45 Taurus 1-11 M100 Coma Berenices IN2-4-5 M46 Puppis 1-6 M101 Ursa Major 4 M47 Puppis 1-6 M102 Draco 4 M48 Hydra 6 M103 Cassiopeia 7 M49 Virgo 2-IN1-8 M104 Virgo 5-9-10 M50 Monoceros 1-6 M105 Leo 5 M51 Canes Venatici 4-10 M106 Canes Venatici 4-5 M52 Cassiopeia 7 M107 Ophiuchus 2 M53 Coma Berenices 4-5-10 M108 Ursa Major 4 M54 Sagittarius 2-IN1-8 M109 Ursa Major 4-5 M55 Sagittarius 2-8 M110 Andromeda 7-11 Messier Object List # NGC# Constellation Type Name, If Any Mag. -

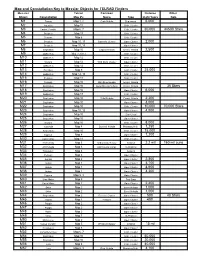

Messier Checklist and Charts

Map and Constallation Key to Messier Objects for TELRAD Finders Messier Telrad Common Distance Other Object Constallation Map #'s Name Type Light Years Data M1 Taurus Map 1, 2 Crab Nebula Supernova 6,000 M2 Aquarius Map 11 Glob. Cluster M3 Canies Venatici Map 6, 7 Glob. Cluster 30,000 44500 Stars M4 Scorpius Map 13 Glob. Cluster M5 Serpens Map 6 Glob. Cluster M6 Scorpius Map 10, 13 Butterfly Cluster Open Cluster 2,000 M7 Scorpius Map 10, 13 Open Cluster M8 Sagittarius Map 10 Lagoon Nebula Emmi. Nebula 2,500 M9 Ophiuchus Map 12,10,13 Glob. Cluster M10 Ophiuchus Map 12 Glob. Cluster M11 Scutum Map 12 Wild Duck Cluster Open Cluster M12 Ophiuchus Map 12 Glob. Cluster M13 Hercules Map 9 Glob. Cluster 25,000 M14 Ophiuchus Map 12, 10 Glob. Cluster M15 Pegasus Map 11 Glob. Cluster M16 Serpens Map 10 Star-Queen/Eagle Emmi. Nebula M17 Sagittarius Map 10 Swan/Omega Nebula Emmi. Nebula 35 Stars M18 Sagittarius Map 10 Open Cluster 6,000 M19 Ophiuchus Map 13 Glob. Cluster M20 Sagittarius Map 10 Trifid Nebula Emmi. Nebula 2,200 M21 Sagittarius Map 10 Open Cluster 3,000 M22 Sagittarius Map 10 Glob. Cluster 10,000 70,000 Stars M23 Sagittarius Map 10, 12 Open Cluster 4,500 M24 Sagittarius Map 10 Star Cloud M25 Sagittarius Map 10 Open Cluster M26 Scutum Map 10 Glob. Cluster 5,000 M27 Vupecula Map 8 Dumbell Nebula Planatary Neb. 1,250 M28 Sagittarius Map 10 Glob. Cluster 15,000 M29 Cygnus Map 8 Open Cluster 7,200 M30 Capricornus Map 11 Glob.