The Ghanaian Infrastructure for Peace: a Successful Grassroots Peacebuilding Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dayi District

SOUTH DAYI DISTRICT i Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the South Dayi District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Creating Opportunities for Youth in Ghana's Cocoa Sector FINAL 19

Working Paper 511 Creating opportunities for young people in Ghana’s cocoa sector Alexandra Löwe June 2017 About Youth Forward The Youth Forward initiative is a partnership led by The MasterCard Foundation, the Overseas Development Institute, Global Communities, Solidaridad, NCBA-CLUSA and GOAL. Its focus is to link young people to quality employment or to starting their own businesses in the agriculture and construction sectors in Ghana and Uganda. The Youth Forward Learning Partnership works across the initiative to develop an evidence-informed understanding of the needs of young people in Ghana and Uganda and how the programme can best meet those needs. The Learning Partnership is led by the Overseas Development Institute in the UK, in partnership with Development Research and Training in Uganda and Participatory Development Associates in Ghana. Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. © Overseas Development Institute 2017. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0) Cover photo: Luliana, child of a cocoa farmer in Ghana. -

The Volt a Resettlement Experience

The Volt a Resettlement Experience edited, by ROBERT CHAMBERS PALL MALL PRESS LONDON in association with Volta River Authority University of Science and Technology Accra Kumasi INSTITUTI OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY Published by the Pall Mall Press Ltd 5 Cromwell Place, London swj FIRST PUBLISHED 1970 © Pall Mall Press, 1970 SBN 269 02597 9 Printed in Great Britain by Western Printing Services Ltd Bristol I CONTENTS PREFACE Xlll FOREWORD I SIR ROBERT JACKSON I. INTRODUCTION IO ROBERT CHAMBERS The Preparatory Commission Policy: Self-Help with Incentives, 12 Precedents, Pressures and Delays, 1956-62, 17 Formulating a New Policy, 1961-63, 24 2. THE ORGANISATION OF RESETTLEMENT 34 E. A. K. KALITSI Organisation and Staffing, 35 Evolution of Policy, 39 Housing and compensation policy, 39; Agricultural policy, 41; Regional planning policy, 42 Execution, 44 Demarcation, 44; Valuation, 45; Social survey, 46; Site selection, 49; Clearing and construction, 52; Evacuation, 53; Farming, 55 Costs and Achievements, 56 3. VALUATION, ACQUISITION AND COMPENSATION FOR PURPOSES OF RESETTLEMENT 58 K. AMANFO SAGOE Scope and Scale of the Exercise, 59 Public and Private Rights Affected, 61 Ethical and Legal Bases for the Government's Compensation Policies, 64 Valuation and Compensation for Land, Crops and Buildings, 67 Proposals for Policy in Resettlements, 72 Conclusion, 75 v CONTENTS 4. THE SOCIAL SURVEY 78 D. A. P. BUTCHER Purposes and Preparation, 78 Executing the Survey, 80 Processing and Analysis of Data, 82 Immediate Usefulness, 83 Future Uses for the Survey Data, 86 Social Aspects of Housing and the New Towns, 88 Conclusion, 90 5. SOCIAL WELFARE IO3 G. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Volta Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT VOLTA REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: Martin K. Yeboah Augusta Okantey Emmanuel Nii Okang Tawiah Edited by: N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah Chief Editor: Nii Bentsi-Enchill ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels. -

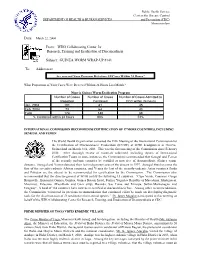

GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To

Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES and Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: March 22, 2004 From: WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis Subject: GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To: Addressees Are you and Your Program Detecting All Cases Within 24 Hours? What Proportion of Your Cases Were Detected Within 24 Hours Last Month? Nigeria Guinea Worm Eradication Program Number of Cases Number of Cases Number of Cases Admitted to Reported Contained CCC within 24 hours Jan. 2004 101 81 45 Feb. 2004 73 64 43 Total 174 145 88 % Contained within 24 hours 83% 51% INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION RECOMMENDS CERTIFICATION OF 17 MORE COUNTRIES, INCLUDING SENEGAL AND YEMEN The World Health Organization convened the Fifth Meeting of the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication (ICCDE) at WHO headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland on March 9-11, 2004. This was the first meeting of the Commission since February 2000. After thorough review of materials submitted, including reports of International Certification Teams in some instances, the Commission recommended that Senegal and Yemen of the recently endemic countries be certified as now free of dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). Senegal and Yemen detected their last indigenous cases of the disease in 1997. Senegal thus becomes the first of the recently-endemic African countries, and Yemen the last of the recently-endemic Asian countries (India and Pakistan are the others) to be recommended for certification by the Commission. The Commission also recommended that the director-general of WHO certify the following 15 countries: “Cape Verde, Comoros, Congo Brazzaville, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Israel, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Palestine (West-Bank and Gaza strip), Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Serbia-Montenegro, and Uruguay”. -

University of G Institute of African Studies 3U C B

UNIVERSITY OF G INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES 18 JUN1969 DEVEL0PMEN1 MUDIES "W 91/ 3 ) W O Jt. LIBRARY 3UCBAJ IS TER 1966 UNIVERSITY OF GHANA INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES RESEARCH REVIEW VOL. 3 NO.1 MICHAELMAS TERM 1966 RESEARCH REVIEW CONTENTS INSTITUTE NEWS Staff......................... • • • p. 1 LONG ARTICLE African Studies in Germany, Past and Present.................... p. 2 PRO JECT REPORTS The Ashanti Research Project................ P*|9 Arabic Manuscripts........... ............. .................................. p .19 INDIVIDUAL RESEARCH REPORTS A Study in Urbanization - Progress report on Obuasi Project.................................................................... p.42 A Profile on Music and movement in the Volta Region Part I . ............................................. ........................ p.48 Choreography and the African Dance. ........................ p .53 LIBRARY AND MUSEUM REPORTS Seminar Papers by M .A . Students. .................. p .60 Draft Papers................................................... ........ p .60 Books donated to the Institute of African Studies............. p .61 Pottery..................................................................... p. 63 NOTES A note on a Royal Genealogy............................... .......... p .71 A note on Ancestor Cult in Ghana ................. p .74 Birth rites of the Akans ..................................... p.78 The Gomoa Otsew Trumpet Set........... ............. ............. p.82 ******** THE REVIEW The regular inflow of letters from readers -

Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT on TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION

DOCUMENTS ~/lt\~TEfR · T/1107 · INDEX IJ!\!IT hwvJ J S£P ~ 4 J954 UNITED NATIONS .. .. United Nations Visiting/ Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION . "' TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS ', . TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : THIRTEENTH SESSION (28 January - 25 March 1954) '/ SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 >1 :p .. ) UNITED NATIONS United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : TIDRTEENTH SESSION (28 January-25 March 1954) SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 NOTE By its resolution 867 (XIII), adopted on 22 March 1954, the Trusteeship Council decided that the reports of the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952, including its special report on the Ewe and Togoland unifi cation problem, should be printed, together with the relevant observations of the Administering Authorities and the text of resolution 867 (XIII) concerning the Mission's reports. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. T/1107 March 1954 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Report on Togoland nnder United Kingdom administration submitted by the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 Letter dated 5 March 1953 from the Chairman of the Visiting Mission to the Secretary- General ............................................................ Foreword................................................................... 1 PART ONE Introduction 2 Itinerary . 3 PART TWO CHAPTER l. - POLITICAL ADVANCEMENT A. Integration with the Gold Coast . 5 B. Local government . -

Mapping Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities in Ghana

MAPPING FOREST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES IN GHANA 1 Assessment of Forest Landscape Restoration Assessing and Capitalizing on the Potential to Potential In Ghana To Contribute To REDD+ Enhance Forest Carbon Sinks through Forest Strategies For Climate Change Mitigation, Landscape Restoration while Benefitting Poverty Alleviation And Sustainable Forest Biodiversity Management FLR Opportunities/Potential in Ghana 2 PROCESS National Assessment of Off-Reserve Areas Framework Method Regional Workshops National National National - Moist Stakeholders’ Assessment of validation - Transition Workshop Forest Reserves Workshop - Savannah - Volta NREG, FIP, FCPF, etc 3 INCEPTION WORKSHOP . Participants informed about the project . Institutional commitments to collaborate with the project secured . The concept of forest landscape restoration communicated and understood . Forest condition scoring proposed for reserves within and outside the high forest zone 4 National Assessment of Forest Reserves 5 RESERVES AND NATIONAL PARKS IN GHANA Burkina Faso &V BAWKU ZEBILLA BONGO NAVRONGO TUMU &V &V &V &V SANDEMA &V BOLGATANGA &V LAWRA &V JIRAPA GAMBAGA &V &V N NADAWLI WALEWALE &V &V WA &V GUSHIEGU &V SABOBA &V SAVELUGU &V TOLON YENDI TAMALE &V &V &V ZABZUGU &V DAMONGO BOLE &V &V BIMBILA &V Republic of SALAGA Togo &V NKWANTA Republic &V of Cote D'ivoire KINTAMPO &V KETE-KRACHI ATEBUBU WENCHI KWAME DANSO &V &V &V &V DROBO TECHIMAN NKORANZA &V &V &V KADJEBI &V BEREKUM JASIKAN &V EJURA &V SUNYANI &V DORMAA AHENKRO &V &V HOHOE BECHEM &V &V DONKORKROM TEPA -

Hohoe Municipal Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA HOHOE MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY COMPOSITE PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET FOR 2017 2017 Composite Programme Based Budget PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW ........................................................................... 4 GSGDA II POLICY OBJECTIVES .......................................................................... 4 GOAL ........................................................................................................................ 5 CORE FUNCTIONS ................................................................................................. 5 POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS .......................................... 6 SUMMARY OF KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2016 ................................................. 8 REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE TRENDS FOR THE MEDIUM-TERM .......... 9 PART B: BUDGET PROGRAMME SUMMARY ................................... 12 PROGRAMME 1: MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION .......................................... 12 PROGRAMME 1: Management and Administration .......................................... 13 SUB -PROGRAMME 1.1 General Administration .................................... 13 SUB -PROGRAMME 1.2 Finance and Revenue Mobilization ................... 16 SUB -PROGRAMME 1.3 Planning, Budgeting and Coordination ............ 18 SUB -PROGRAMME 1.4 Human Resource Management ................................ 21 SUMMARY OF EXPENDITURE BY SUB-PROGRAMME AND ECONOMIC CLASSIFICATION ............................................................................................. 22 PROGRAMME 2: SOCIAL SERVICES -

A Ground-Water Reconnaissance of the Republic of Ghana, with a Description of Geohydrologic Provinces

A Ground-Water Reconnaissance of the Republic of Ghana, With a Description of Geohydrologic Provinces By H. E. GILL r::ONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-K Prepared in cooperation with the Volta River Authority, the Ghana .Division of Water Supplies, and the r;eological Survey of Ghana under the .FJuspices of the U.S. Agency for lnterttational Development rJNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government F"inting Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract__________________________________________________________ K 1 Introduction------------------------------------------------------ 2 Purpose and scope___ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 2 Previous investigations_________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgments_____________________________________________ 3 GeographY--------------------------------------------------- 3 Clinaate------------------------------------------------------ 5 GeohydrologY----------------------------------------------------- 6 Precarnbrianprovince__________________________________________ 7 Lower Precambrian subprovince_____________________________ 7 Middle Precambrian subprovince____________________________ 8 Upper Precambrian subprovince_____________________________ 10 Voltaianprovince----------------------------------------------