1 Oregon Shakespeare Festival Lessons for Much Ado About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Perfect-Fluid Cylinders and Walls-Sources for the Levi-Civita

Perfect-fluid cylinders and walls—sources for the Levi–Civita space–time Thomas G. Philbin∗ School of Mathematics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland Abstract The diagonal metric tensor whose components are functions of one spatial coordinate is considered. Einstein’s field equations for a perfect-fluid source are reduced to quadratures once a generating function, equal to the product of two of the metric components, is chosen. The solutions are either static fluid cylinders or walls depending on whether or not one of the spatial coordinates is periodic. Cylinder and wall sources are generated and matched to the vacuum (Levi– Civita) space–time. A match to a cylinder source is achieved for 1 <σ< 1 , − 2 2 where σ is the mass per unit length in the Newtonian limit σ 0, and a match → to a wall source is possible for σ > 1 , this case being without a Newtonian | | 2 limit; the positive (negative) values of σ correspond to a positive (negative) fluid density. The range of σ for which a source has previously been matched to the Levi–Civita metric is 0 σ< 1 for a cylinder source. ≤ 2 1 Introduction arXiv:gr-qc/9512029v2 7 Feb 1996 Although a large number of vacuum solutions of Einstein’s equations are known, the physical interpretation of many (if not most) of them remains unsettled (see, e.g., [1]). As stressed by Bonnor [1], the key to physical interpretation is to ascertain the nature of the sources which produce these vacuum space–times; even in black-hole solutions, where no matter source is needed, an understanding of how a matter distribution gives rise to the black-hole space–time is necessary to judge the physical significance (or lack of it) of the complete analytic extensions of these solutions. -

About the Course • an Introduction and 61 Lessons Review Proper Posture and Hand Position, Home Row Placement, and the Concepts Taught in Typing 1 and 2

About the Course • An introduction and 61 lessons review proper posture and hand position, home row placement, and the concepts taught in Typing 1 and 2. The lessons also increase typing speed and teach the following typing skills: all numbers; tab key; colon, slash, parentheses, symbols, and plus and minus signs; indenting and centering; and capitalization and punctuation rules. • This course uses beautifully designed pages with images of nature for those who are looking for an inexpensive, effective, fun, offline program with a “good and beautiful” feel. The course supports high moral character and gives fun practice—all without the need for flashy and over-stimulating effects that often come with on-screen computer programs. • This course is designed for children who have completed The Good & the Beautiful Typing 2 course or have had the same level of typing experience. Items Needed • Course book and sticker sheet • A laptop or computer with a basic word processing program, such as Word, Pages, or Google Docs • Easel document holder (for standing the course book next to the computer) How the Course Works • The child should complete 1 or more lessons a day, 2–5 days a week. (Lessons take 5–15 minutes, depending on the speed of the child.) The child checks off the shell check box each time a lesson is completed. • To complete a lesson, the child places the course book on an easel document holder next to the laptop or computer and follows the instructions, typing assignments in a basic word processing program. • When a page is completed, the child chooses a sticker and places it on the page where indicated. -

Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register SIX-MODE

United States Copyright Office Library of Congress · 101 Independence Avenue SE · Washington, DC 20559-6000 · www.copyright.gov June 12, 2017 Paul Juhasz The Juhasz Law Firm, P.C. 10777 Westheimer, Suite 1100 Houston, TX 77042 Re: Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register SIX-MODE SIMULATOR, and EIGHT-MODE SIMULATOR; Correspondence ID: 1- lJURlDF; SR 1-3302420841, and 1-3302420241 Dear Mr. Juhasz: The Review Board of the United States Copyright Office (the "Board") considered Amcrest Global Holdings Limited's ("Amcrest") second request for reconsideration of the Registration Program's refusal to register claims in two-dimensional artwork for the works titled "SIX-MODE SIMULATOR" and "EIGHT-MODE SIMULATOR" (the "Works"). After reviewing the applications, deposit copies, and relevant correspondence, along with the arguments in the second request for reconsideration, the Board finds that the Works exhibit copyrightable authorship and thus may be registered. SIX-MODE SIMULATOR is a screen print of a device screen. A clock symbol, a number display, and the battery symbol appear at the top. Below that are six mini screens, each containing a set of roman numerals ( either I and II, or I, II, 111). The mini screens also contain varying arrangements of lines and dots. Below the mini screens are two volume/intensity control symbols (a series of thick dash symbols with the plus and minus signs on either side of the series of dashes), one preceded by the roman numeral I and the other preceded by the roman numeral II. EIGHT-MODE SIMULATOR is also a screen print of a device screen. -

Chapter 13. TABULAR WORK

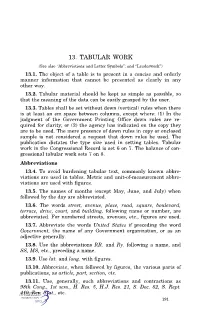

13. TABULAR WORK (See also ‘‘Abbreviations and Letter Symbols’’; and ‘‘Leaderwork’’) 13.1. The object of a table is to present in a concise and orderly manner information that cannot be presented as clearly in any other way. 13.2. Tabular material should be kept as simple as possible, so that the meaning of the data can be easily grasped by the user. 13.3. Tables shall be set without down (vertical) rules when there is at least an em space between columns, except where: (1) In the judgment of the Government Printing Office down rules are re- quired for clarity; or (2) the agency has indicated on the copy they are to be used. The mere presence of down rules in copy or enclosed sample is not considered a request that down rules be used. The publication dictates the type size used in setting tables. Tabular work in the Congressional Record is set 6 on 7. The balance of con- gressional tabular work sets 7 on 8. Abbreviations 13.4. To avoid burdening tabular text, commonly known abbre- viations are used in tables. Metric and unit-of-measurement abbre- viations are used with figures. 13.5. The names of months (except May, June, and July) when followed by the day are abbreviated. 13.6. The words street, avenue, place, road, square, boulevard, terrace, drive, court, and building, following name or number, are abbreviated. For numbered streets, avenues, etc., figures are used. 13.7. Abbreviate the words United States if preceding the word Government, the name of any Government organization, or as an adjective generally. -

STYLE GUIDE for PLANCK PAPERS

STYLE GUIDE for PLANCK PAPERS C. R. Lawrence, T. J. Pearson, Douglas Scott, L. Spencer, A. Zonca 2013 February 6 Version 2013 February 6 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PURPOSE 1 2 HOW TO REFER TO THE PLANCK PROJECT 1 3 HOW TO REFER TO PLANCK CATALOGUES AND CRYOCOOLERS 1 4 DATES 1 5 ACRONYMS, AND ACTIVE LINKS 2 6 TITLE 2 7 ABSTRACT 2 8 CORRESPONDING AUTHOR AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 9 UNITS 3 10 NOTATION 4 11 PUNCTUATION, ABBREVIATIONS, AND CAPITALIZATION 4 12 CONTENT 5 13 USE OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE 5 14 LaTEX AND TEX; TYPESETTING MATHEMATICS 8 15 REFERENCES 10 16 FIGURES 10 16.1 From the A&A Author’s Guide 10 16.2 Requirements for line plots 11 16.3 Examples of line plots 12 16.4 Requirements for all-sky maps 13 16.5 Requirements for figures with shading 13 16.6 Additional points 13 17 Fixes for two annoying LaTEX problems 16 18 TABLES 16 18.1 Tutorial on Tables 18 18.2 Columns 19 18.3 Centring, etc. in columns 19 18.4 Rules 20 18.5 Space between columns 20 18.6 Space between rows 22 18.7 How to override the template for a particular entry 23 18.8 More on rules 23 18.9 Centring a table 24 18.10 How to make a table of a specified width 24 ii Version 2013 February 6 18.11 How to run something across more than one column 24 18.12 Leaders: filling up a column with rules or dots 25 18.13 How to line up columns of numbers 26 18.14 Adding footnotes to a table 28 18.15 Paragraphs as table entries 30 Version 2013 February 6 4 DATES 1 1 PURPOSE This Style Guide is intended to help authors of Planck-related papers prepare high-quality manu- scripts in a uniform style. -

UEB Guidelines for Technical Material

Guidelines for Technical Material Unified English Braille Guidelines for Technical Material This version updated October 2008 ii Last updated October 2008 iii About this Document This document has been produced by the Maths Focus Group, a subgroup of the UEB Rules Committee within the International Council on English Braille (ICEB). At the ICEB General Assembly in April 2008 it was agreed that the document should be released for use internationally, and that feedback should be gathered with a view to a producing a new edition prior to the 2012 General Assembly. The purpose of this document is to give transcribers enough information and examples to produce Maths, Science and Computer notation in Unified English Braille. This document is available in the following file formats: pdf, doc or brf. These files can be sourced through the ICEB representatives on your local Braille Authorities. Please send feedback on this document to ICEB, again through the Braille Authority in your own country. Last updated October 2008 iv Guidelines for Technical Material 1 General Principles..............................................................................................1 1.1 Spacing .......................................................................................................1 1.2 Underlying rules for numbers and letters.....................................................2 1.3 Print Symbols ..............................................................................................3 1.4 Format.........................................................................................................3 -

Spanish and UEB

AUSTRALIAN BRAILLE AUTHORITY A subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities Inc. www.brailleaustralia.org email: [email protected] Spanish and UEB Introduction This document should be read in conjunction with the Australian Braille Authority, Guidelines for Foreign Language Material, 2019 which can be found on the brailleaustralia.org website. Follow these guidelines when transcribing Spanish for educational purposes, such as Spanish language textbooks, examination papers, grammar and phrase books, bilingual dictionaries, etc. Spanish within an English context such as a novel should use the guidelines given in 1.1 of the Australian Braille Authority, Guidelines for Foreign Language Material, 2019. A more complete Spanish code may be requested for higher education or by a native reader. This is not covered in detail in this document. Relevant DBT codes are however given in the section on DBT. Kathy Riessen, Editor May 2019 Contractions Transcribe Spanish text uncontracted using the accents as listed below. Punctuation Use UEB punctuation, indicators and numeral conventions except for the exclamation and question marks. Spanish places inverted question and exclamation marks at the beginning of questions and exclamatory sentences and the standard marks at the end of the sentence. The UEB symbols for the inverted question and exclamation marks are 3 cells, so the Spanish conventions are used for these punctuation signs. 1 ABA: Spanish and UEB May 2019 Quotation signs in Spanish may sometimes be shown as the standard quotation signs as used in English and sometimes as guillemets (angled quotation signs). Generally these should be transcribed as the UEB single cell non-specific quotation signs. -

Publications Handbook Style Manual&

Publications Handbook Style Manual& American Society of Agronomy Crop Science Society of America Soil Science Society of America Publications Handbook and Style Manual American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America Updated February 2021 Publications Handbook and Style Manual Chapter 1: Manuscript Preparation Chapter 2: Style Chapter 3: Specialized Terminologies Chapter 4: Statistical Design and Analysis Chapter 5: Tables and Figures Chapter 6: Mathematics and Numbers Chapter 7: Units and Measurement Chapter 8: Journal Procedures Chapter 9: Procedures for Monographs, SSSA Book Series, Books, and Other Publications Chapter 10: Copyright and Permission to Publish Appendix A: Online Resources Appendix B: Software Papers and Case Studies References and Selected Bibliography © American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America 2021 Chapter 1. Manuscript Preparation The American Society of Agronomy (ASA), Crop Science Society of America (CSSA), and Soil Science Society of America (SSSA) have a reputation for publishing high-quality papers in their journals, books, and other publications. Authors are strongly urged to have their papers thoroughly reviewed by competent colleagues before submitting those papers for consideration by any ASA, CSSA, and SSSA publication. The format used in ASA, CSSA, and SSSA journals differs from that used in books, special publications, and other media (see Chapter 9). This chapter deals mainly with jour- nal formats, but the discussion applies broadly to the other formats. Publications of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA for the most part follow the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th edition (APA, 2020). For ques- tions of scientific style and format beyond what is covered in this manual and the APA Publication Manual, consult the style manuals of the American Chemical Society (Coghill & Garson, 2006) and the Council of Science Editors (CSE, 2006). -

Braille Mathematics Notation

BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF THE UNITED KINGDOM BRAILLE MATHEMATICS NOTATION Royal National Institute of the Blind Bakewell Road Orton Southgate Peterb orough Cambridgeshire PE XU c Braille Authority of the United Kingdom Registered Charity No Printed by RNIB Peterb orough CONTENTS Memb ers of the Mathematics Committee ii Memb ers of the JointTechnical Committee ii Intro duction to edition iii Intro duction to edition iv Table of braille mathematical signs Mo dication of signs Braille Mathematics Notation General remarks Numeral and letter signs The spacing of braille signs The oblique stroke and fraction line Brackets Indices Sp ecial functions and other words and abbreviations Delimiting the argument of a function Co ordinates and sets Matrices determinants and other arrays Worked calculations logical gures Miscellaneous notation Layout of mathematical text Units Alphab ets used in mathematics Index i MEMBERS OF THE MATHEMATICS COMMITTEE A W Chatters Chairman Bristol University J A Allnut Central -

Chapter 6. Mathematics and Numbers

Chapter 6. Mathematics and Numbers EQUATIONS Mathematical equations can present difficult and costly problems of type composi- tion. Because equations often must be retyped and reformatted during composition, errors can be introduced. Keep in mind that typesetters will reproduce what they see rather than what the equation should look like. Therefore, preparation of the manuscript copy and all directions and identification of letters and symbols must be clear, so that those lacking in mathematical expertise can follow the copy. Use keyboard formatting where possible (i.e., bold, super-/subscripts, simple vari- ables, Greek font, etc.), and use MathType or the Word equation editor for display equa- tions. If your equations are drawn from calculations in a computer language, translate the equation syntax of the computer language into standard mathematical syntax. Likewise, translate variables into standard mathematical format. If you need to present computer code, do that in an appendix. Position and Spacing The position and spacing of all elements of an equation must be exactly as they are to appear in printed form. Place superscript and subscript letters and symbols in the correct positions. Put a space before and after most mathematical operators (the main exception is the soli- dus sign for division). For example, plus and minus signs have a space on both sides when they indicate a mathematical operation but have no space between the sign and the number when used to indicate positive or negative position on the number line (e.g., 5 - 2 = 3; a range from -15 to 25 kg). No space is left between variables and their quantities or between multiplied quan- tities when the multiplication sign is not explicitly shown. -

KIF3A Is a New Microtubule-Based Anterograde Motor in the Nerve Axon

KIF3A Is a New Microtubule-based Anterograde Motor in the Nerve Axon Satoru Kondo, Reiko Sato-Yoshilake, Yasuko Noda, Hiroyuki Aizawa, Takao Nakata, Yoshiharu Matsuura,* and Nobutaka Hirokawa Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Hongo, Tokyo 113, Japan; and *Laboratory of Hepatitis Viruses, Department of Virology II, National Institute of Health, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162, Japan Abstract. Neurons are highly polarized cells com- complex axonal transports seems quite likely. Here we posed of dendrites, cell bodies, and long axons. Be- characterized a new member of the kinesin super- cause of the lack of protein synthesis machinery in family, KIF3A (50-nm rod with globular head and tail), axons, materials required in axons and synapses have and found that it is localized in neurons, associated to be transported down the axons after synthesis in the with membrane organdie fractions, and accumulates cell body. Fast anterograde transport conveys different with anterogradely moving membrane organelles after kinds of membranous organelles such as mitochondria ligation of peripheral nerves. Furthermore, native and precursors of synaptic vesicles and axonal mem- KIF3A (a complex of 80/85 KIF3A heavy chain and a branes, while organdies such as endosomes and au- 95-kD polypeptide) revealed microtubule gliding activ- tophagic prelysosomal organelles are conveyed retro- ity and baculovirus-expressed KIF3A heavy chain gradely. Although kinesin and dynein have been demonstrated microtubule plus end-directed (antero- identified as good candidates for microtubule-based grade) motility in vitro. These findings strongly sug- anterograde and retrograde transporters, respectively, gest that KIF3A is a new motor protein for the antero- the existence of other motors for performing these grade fast axonal transport.