3. the Context of Private Participation in Infrastructure in Tunisia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Projets D'assainissement Inscrit S Au Plan De Développement

1 Les Projets d’assainissement inscrit au plan de développement (2016-2020) Arrêtés au 31 octobre 2020 1-LES PRINCIPAUX PROJETS EN CONTINUATION 1-1 Projet d'assainissement des petites et moyennes villes (6 villes : Mornaguia, Sers, Makther, Jerissa, Bouarada et Meknassy) : • Assainissement de la ville de Sers : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés (mise en eau le 12/08/2016); * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Bouarada : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : les travaux sont achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Meknassy * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. • Makther: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2018. * Travaux complémentaires des réseaux d’assainissement : travaux en cours 85% • Jerissa: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 12/09/2014 ; * Réseaux d’assainissement : travaux achevés (Réception provisoire le 25/09/2017). • Mornaguia : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés Composantes du Reliquat : * Assainissement de la ville de Borj elamri : • Tranche 1 : marché résilié, un nouvel appel d’offres a été lancé, travaux en cours de démarrage. 1 • Tranche2 : les travaux de pose de conduites sont achevés, reste le génie civil de la SP Taoufik et quelques boites de branchement (problème foncier). * Acquisition de 4 centrifugeuses : Fourniture livrée et réceptionnée en date du 19/10/2018 ; * Matériel d’exploitation: Matériel livré et réceptionné ; * Renforcement et réhabilitation du réseau dans la ville de Meknassy : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 11/02/2019. -

Rapport Sur Les Entreprises Publiques

République Tunisienne Ministère de l'économie, des finances et de l'appui à l'investissement Rapport sur Les entreprises publiques Traduction française élaborée dans le cadre du projet d’appui aux réformes budgétaire et comptable mis en œuvre par Expertise France et financé par l’Union Européenne. La version arabe officielle fait foi. 1 TABLE DES MATIERES Rubriques Pages -Introduction :…………………………………………………… 3-4 -Première partie :La situation économique et financière des entreprises publiques :………………………………………………………. 5-29 -Chapitre premier :Présentation des entreprises publiques…………... 6-20 -Chapitre deux :Indicateurs d’activité et indicateurs financiers durant la période 2017-2018………………………………………………….. 20-29 -Deuxième partie :Analyse de la situation financière d’un échantillon 30-134 de 33 entreprises publiques durant la période 2017-2019 :…………………… -Chapitre premier :Les entreprises publiques actives dans le secteur financier et assimilé …………………………………………………………… 34-45 -Chapitre deux :Les caisses sociales ……………………………... 45-53 -Chapitre trois :Situation financière de 23 entreprises publiques.... 54-134 -Troisième partie :Relation financière entre l’Etat et les entreprises 135-179 publiques :……………………………………………………………………… -Chapitre premier :Dettes et créances entre l’Etat et les entreprises publiques………………………………………………………………………. 136-151 -Chapitre deux :Les besoins financiers des entreprises publiques et la charge de leur restructuration durant la période 2017-2020……………… 151-165 -Chapitre trois :Liquidité des entreprises publiques…………….. 165-179 -

Assessing Aquifer Water Level and Salinity for a Managed Artificial

water Article Assessing Aquifer Water Level and Salinity for a Managed Artificial Recharge Site Using Reclaimed Water Faten Jarraya Horriche and Sihem Benabdallah * Centre of Water Research and Technologies, Geo-resources Laboratory, Techno-park Borj-Cedria, BP 273 Soliman, Tunisia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +216-98-404-777 Received: 11 December 2019; Accepted: 20 January 2020; Published: 25 January 2020 Abstract: This study was carried out to examine the impact of an artificial recharge site on groundwater level and salinity using treated domestic wastewater for the Korba aquifer (north eastern Tunisia). The site is located in a semi-arid region affected by seawater intrusion, inducing an increase in groundwater salinity. Investigation of the subsurface enabled the identification of suitable areas for aquifer recharge mainly composed of sand formations. Groundwater flow and solute transport models (MODFLOW and MT3DMS) were then setup and calibrated for steady and transient states from 1971 to 2005 and used to assess the impact of the artificial recharge site. Results showed that artificial recharge, with a rate of 1500 m3/day and a salinity of 3.3 g/L, could produce a recovery in groundwater level by up to 2.7 m and a reduction in groundwater salinity by as much as 5.7 g/L over an extended simulation period. Groundwater monitoring for 2007–2014, used for model validation, allowed one to confirm that the effective recharge, reaching the water table, is less than the planned values. Keywords: artificial recharge; groundwater; treated wastewater 1. Introduction Water is a critical resource in many Mediterranean countries because of its scarcity and uneven geographical, seasonal, and inter-annual distribution [1,2]. -

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region In

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation EI JR 15 - 201 Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation Italy Tunisia Location of Tunisia Algeria Libya Tunisia and surrounding countries Legend Gafsa – Ksar International Airport Airport Gabes Djerba–Zarzis Seaport Tozeur–Nefta Seaport International Airport International Airport Railway Highway Zarzis Seaport Target Area (Six Governorates in the Southern -

2 Tunisia Logistics Infrastructure

2 Tunisia Logistics Infrastructure Logistics Infrastructure Investment Cargo Concerns Highways Concerns Roads Concerns Aviation Concerns Air Transport Concerns Infrastructure Upgrade Air Freight Concerns Maritime Concerns Port Development related issues Customs Clearance Concerns Railway Concerns In accordance with Decree No. 2014-209 of January 16, 2014, the mission of the Ministry of Transport is to establish, maintain and develop a comprehensive, integrated and coordinated transport system in Tunisia. The ministry is responsible for: The development and implementation of state transportation policies and programs; to give an opinion on on regional development programs and on infrastructure projects relating to transportation; carry out sectoral research and prospective studies, implement strategies for the development and modernization of the transport system, draw up transport master plans in coordination with the parties concerned and ensure their implementation; ensure the development of human resources in the field of transport; draw up programs and plans relating to transport safety and the quality of services and ensure their implementation; oversee the development and monitoring of the implementation of national civil aviation, commercial seaports and maritime transport security programs; participate in the development of tax policies in transportation; study and prepare draft legislative and regulatory texts relating to transportation; participate in the development and execution of programs to control energy consumption, the -

RAISON SOCIALE ADRESSE CP VILLE Tél. Fax RESPONSABLES

Secteur RAISON SOCIALE ADRESSE CP VILLE Tél . Fax RESPONSABLES d’Activité 2MB Ing conseil Cité Andalous Immeuble D Appt. 13 5100 Mahdia 73 694 666 BEN OUADA Mustapha : Ing conseil ABAPLAST Industrie Rue de Entrepreneurs Z.I. 2080 Ariana 71 700 62 71 700 141 BEN AMOR Ahmed : Gérant ABC African Bureau Consult Ing conseil Ag. Gafsa: C-5, Imm. B.N.A. 2100 Gafsa 76 226 265 76 226 265 CHEBBI Anis : Gérant Ag. Kasserine: Av Ali Belhaouène 1200 Kasserine 34, Rue Ali Ben Ghédhahem 1001 Tunis 71 338 434 71 350 957 71 240 901 71 355 063 ACC ALI CHELBI CONSULTING Ing conseil 14, Rue d'Autriche Belvédère 1002 Tunis 71 892 794 71 800 030 CHELBI Ali : Consultant ACCUMULATEUR TUNISIEN (L’) Chimie Z.I. de Ben Arous B.P. N° 7 2013 Ben Arous 71 389 380 71 389 380 Département Administratif & ASSAD Ressources Humaines ACHICH MONGI Av 7 Novembre Imm AIDA 2éme Achich Mongi Ingénieur Conseil Etudes et Assistances Technique Ing conseil Etage bloc A N°205 3000 Sfax 74 400 501 74 401 680 [email protected] ACRYLAINE Textile 4, Rue de l'Artisanat - Z.I. Charguia II 2035 Tunis 71 940 720 71 940 920 [email protected] Carthage Advanced e- Technologies Electronique Z.I. Ariana Aéroport – Imm. Maghrebia - 1080 Tunis Cdx 71 940 094 71 941 194 BEN SLIMANE Anis: Personnel Bloc A Boulevard 7 Novembre – BP www.aetech-solutions.com 290 ADWYA Pharmacie G.P. 9 Km 14 - B.P 658 2070 Marsa 71 742 555 BEN SIDHOM R. -

New Enfidha International Airport, Tunisia

SIKA AT WORK NEW ENFIDHA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, TUNISIA CONCRETE: Sikament®, Sika® ViscoCrete® REFURBISHMENT: Sika® Ceram®, SikaGrout®, Sika® Carbodur®, Sika® Monotop®, SikaTop®, Sikadur® SEALING & BONDING: Sikasil® ENFIDHA AIRPORT, TUNISIA Tunisia is a country which has promoted its assets well. It has be situated at Enfidha, to the north east of the country about developed facilities for tourism and is now one of the first des- 80 km south of the capital Tunis but in the middle of a major tinations in Africa for holidaying Europeans with year round tourist region. sunshine, excellent hotels, and beaches, fine golf courses, and first class service. ‘Aéroport de Paris’ (ADP) completed the design of the new international airport at Enfidha in the final quarter of 2001 The country contains a large proportion of the Sahara Desert (contact worth $9.6million) and also prepared the tender but even this is an asset to tourism. Tunisia may be reached documents for the contracts relating to the construction in by traveling to one of six international airports around the mid-2006. The construction plans call for building the airport country: Tunis-Carthage (8 kilometers from the capital in several phases; the first phase of the airport will have a Tunis), Jerba-Zarzis Airport, Monastir H.Bourguiba Airport, passenger handling capacity of five million a year. However Sfax-Thyna Airport, Touzeur-Nefta Airport or 7 November- subsequent phases are expected to increase the capacity Tabarka Airport. All these airports are fairly small with limited to ten million and then 20 million in the longer-term. The facilities for the sophisticated air traveler. -

Tunisia 2012

Tunisia 2012 www.africaneconomicoutlook.org Tunisia Tunisia is trying to carry off a delicate political transition against a background of difficult circumstances — post-revolutionary social unrest and instability, the Libyan crisis, and the international crisis. A swift return to social harmony and understanding between those involved in the political process are the main elements on the roadmap indicating the key stages on the way to economic recovery in 2012, together with the setting up of structures for economic governance fit to guarantee investors a legal framework that will encourage prosperous enterprises, making a clean break with the predatory practices of the former regime. Progress has been made in governance in 2011, but the structural problem of youth unemployment requires far-reaching reform, going further than emergency action, whose effects will be felt in the longer term. Overview 2011 saw the revolution of 14 January in Tunisia and its repercussion throughout the Arab world. On 23 October 2011, Tunisia held its first democratic election since independence. The election of the Constituent Assembly allowed the country to move on to a transition phase. This involves the drafting of a new Constitution, laying the foundations for a multi-party democracy based on respect for human rights. The following stage remains delicate, because of the challenge of maintaining social harmony, public security and achieving economic recovery. The political future and economic recovery are closely linked. There can be no economic recovery without stability, and no successful transition to democracy without recovery, providing a tangible response to young people’s aspirations. The revolution revealed the extent of the country’s structural weaknesses: regional disparities, unemployment among young graduates and governance. -

Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia

Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia Investment Opportunities in Inland Areas of Tunisia Regional development in particular in inland areas within the next few years will be one of the major concerns of public authorities. To attract investment in these areas the regional development policy will be focused primarily on five fields: • establishing good regional governance; • developing infrastructure (roads, highways, railway etc.); • strengthening financial and tax incentives; • Improving the living environment; • promoting decentralized international cooperation. Ind industries Leather Ceramics ‐ and Industries electric IT Tourism Transport Manufacturing and Materials Agriculture Handicrafts Agribusiness Garment Chemical Various Building Textile Mechanical Gafsa X X X X X X X Kasserine X X X X X Jendouba X X X X X Siliana X X X X X Kef Beja X X X X X X X Kairouan X X X X X X X X Kebili X X X Tataouine X X X X Medenine X X X X X X Tozeur X X X X Sidi Bouzid X X X X X Gabes X X X X X X X SIDI BOUZID Matrix of Opportunities and Potentials in the Governorate of Sidi Bouzid Sectors Opportunities and potentials Benefits and resources Agriculture and ‐ The possibility to specialize in the production of ‐ The availability of local produce Agribusiness organic varieties in both crops and livestock activity such as meat of the indigenous type (honey, olive oil, sheep Nejdi, camelina Nejdi (Barbarine) ; (Mezzounna), etc..); ‐ soil conditions are most conducive ‐ production of certain tree crops in irrigated good and ground water is -

~~''%Ly-~Tl:S''::-'C';-:T ,T!E..'~"'~,;Jl

~~''%lY-~tl:S''::-'c- - __ ~" :.-0"':" • ';-:t~ ,t!E..'~"'~,;j• l 80nqut €mtrolt bt arunisit Letter of introduction to the 39th Annual Report of the Central Bank of Tunisia on Tunisia's economic, monetary and financial activity in 1997 presented to His Excellency the President of the Republic of Tunisia Moharned El Béji Harnda Governor of the Central Bank of Tunisia Your Excellency the President of the Republic, It is my honour to present you with the thirty-ninth Annual Report of the Central Bank of Tunisia, covering the year 1997. This report analyzes the development of the economic and financial situation during the first year of the ninth development plan, and attempts to evaluate our country's ability to manage the effects of the economic situation and to adapt tofinancial globalization. Mr President, the most outstanding feature of the international situation in 1997 was undoubtedly the major monetary andfinancial crisis that began, in the middle of the year, to shake certain countries of South-East Asia, leading to the collapse of their economies and their financial systems. The resulting domino effect was not only detrimental to the region but had negative repercussions on other areas of the world, confirming once again the "global village" aspect of our planet. The crisis revealed the incoherences in the overall management of the region's economies, which until that time had been considered quite successful, and especially the fact that inflation in these countries was higher than in their partner countriès, a phenomenon which inevitably created an interest rate differential. Added to this were the effects of free circulation of capital in a context of fixed exchange rates pegged to the US dollar. -

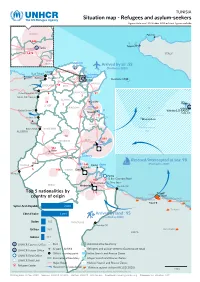

Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Figures/Data As of 31 October 2020 Or Latest Figures Available

TUNISIA Situation map - Refugees and asylum-seekers Figures/data as of 31 October 2020 or latest figures available ARIANA Palerm o 1,044 o Trapani (TP) A Tunis MANOUBA TUNIS 1,476 ITALY BEN AROUS Bizerte 50 h[ Arrived by air :58 41 (Profiled in 2020) BIZERTE Tabaro ka ARIANA Oum Teboul La Goulette D Tunio s o Annaba Nord o Babouch D Malloula CP A h[ MANOUBA Tunis Pantelleria (TP) 9 TUNIS BEN AROUS NABEUL JENDOUBA 18 BEJA D Ouled Moumen CP 6 ZAGHOUAN 51 2 Sakiet Sidi Youssef D SILIANA o 28 Enfidha 3 Valetta LE KEF Sousse o KAIROUAN h[263 A SOUSSE o Valletta Kalaat Sinan CP D Valetta (LO-EASO) Monastir MALTA 11 Lampedusa Haidra CP D 78 MONASTIR o o Lampedusa Tébessi MAHDIA 2 Bou Chebka D KASSERINE Mediterranean ALGERIA Sea 74 1,060 SFAX o SIDI BOUZ h[ Sfax Sfax Sfax o 154 Gafsa GAFSA h[ La Skhirra TUNISIA Rescued/intercepted at sea: 98 o Tozeur Gabes Djerba (Profiled in 2020) TOZEUR ho [ 145 Djerbao h[ Gabès 5 GABES Gabès D 104 Hazoua Û Û Zarzis Û S2 Ben Guerdane Road 922 EE"" E" Ibn Khaldun S1 Olive farm KEBILI Medenine MEDENINE Ras Jdir CP D Top 5 nationalities by 132 Tripoli To ripoli* ¡A Tripoli country of origin Ajaylat Ayn Zarah Garabulli Salah Aldeen ¡¡ ¡ o ¡ Al Khums Tripoli ¡ Syrian Arab Republic 2,010 Zlitan ¡ Tarhuna ¡ Côte d'Ivoire 1,734 Arrived by land : 95 (Profiled in 2020) Sudan 285 TATAOUINE D Dhahiba CP Eritrea 267 Bani Walid¡ LIBYA Guinea 212 h[ A UNHCR Country Office Port Administrative boundary o Airport / Airfield Refugees and asylum-seekers (Governorate total) A UNHCR Liaison Office D Official crossing point Italian Search and Rescue Zones UNHCR Field Office International boundary Libyan Search and Rescue Zones UNHCR Field Unit Û Major Road Maltese Search and Rescue Zones E" Refugee Center Movement of population¡ Violence against civilians (ACLED 2020) 100km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Tunisie, a Special Purpose Company Which Will Be the Concessionaire of the Two Airports

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND TUNISIA TUNISIA - MONASTIR AND ENFHIDA AIRPORTS PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) STUDY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PRIVATE SECTOR DEPARTMENT INFRASTRUCTURE AND PPP DIVISION (OPSM.3) August 22th 2008 Project Name: Tunisia: Monastir and Enfhida Airports Project Country: Tunisia Project Number: XXXXXXXX (Mahib, to be completed) Department: OPSM.3 Date: August 22th, 2008 1. Introduction 1.1 Environmental and social categorization and rational This is a Category 2 project because a limited number of specific environmental and social impacts may result from minor upgrading in the existing airport facilities in Monastir and from construction and operation of the new airport at Enfidha1. These impacts, including land acquisition and resettlement, being implemented by the Government, are being managed, in close detail, to international standards and best practices. The new airport in Enfhida has been planned since a Presidential request of February 1998 and the government has since then conducted various public meetings regarding the proposed developments. The Monastir Airport, located 8 km from the city of Monastir, has been in operation for 40 years; the terminal will undergo minor modification, including safety, security and waste management upgrades, as part of the project. It is worth underlying that the Enfidha Airport is currently under construction (40% have been achieved to date, construction works started in summer 2007) and will meet international standards. 2. Project description and justification Tunisia’s existing airports are either already saturated (Monastir airport handled 4.2 million passengers for a nominal capacity of 3.5 millions) or nearing saturation (Tunis-Carthage airport) during the peak summer months.