Fall 2012 35 Baroque Flute and Earn a Living

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eubo Mobile Baroque Academy

EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY EUROPEAN CO OPERATION PROJECT 2015 2018 INTERIM REPORT Pathways & Performances CONTENTS EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY........................................2?3 PARTNER ORGANISATIONS ....................................................4?13 INTERNATIONAL CONCERT TOURS ....................................14?18 MUSIC EDUCATION ...............................................................19?22 OTHER ACTIVITIES ................................................................23?25 HOW DO WE MAKE ALL THIS HAPPEN ................................26?27 WHO IS WHO................................................................................28 EUBO MOBILE BAROQUE ACADEMY The EUBO Mobile Baroque Academy (EMBA) co-operation project addresses the unequal provision across the European Union of baroque music education and performance, in new and creative ways. The EMBA project builds on the 30-year successful track-record of the European Union Baroque Orchestra (EUBO) in providing training and performing opportunities for young EU period performance musicians and extends and develops possibilities for orchestral musicians intending to pursue a professional career. From an earlier stage of conservatoire training via orchestral experience, through to the first steps in the professional world, musicians attending the activities of EMBA are offered a pathway into the profession. The EMBA activities supporting the development of emerging musicians include specialist masterclasses by expert tutors; residential orchestral selection -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

Music in the Pavilion

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LIBRARIES KISLAK CENTER Music in the Pavilion PHOTO BY SHARON TERELLO NIGHT MUSIC A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM Friday, September 27, 2019 Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center www.library.upenn.edu/about/exhibits-events/music-pavilion .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................. .................................................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................. ........... ............ ......... A SUBTLE AROMA OF ROMANTICISM NIGHT MUSIC Andrew Willis, piano Steven Zohn, flute Rebecca Harris, violin Amy Leonard, viola Eve Miller, cello Heather Miller Lardin, double bass PIANO TRIO IN D MINOR, OP. 49 (1840) FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–47) MOLTO ALLEGRO AGITATO ANDANTE CON MOTO TRANQUILLO SCHERZO: LEGGIERO E VIVACE FINALE: ALLEGRO ASSAI APPASSIONATO PIANO QUINTET IN A MINOR, OP. 30 (1842) LOUISE FARRENC (1804–75) ALLEGRO ADAGIO NON TROPPO SCHERZO: PRESTO FINALE: ALLEGRO The piano used for this concert was built in 1846 by the Paris firm of Sébastien Érard. It is a generous gift to the Music Department by Mr. Yves Gaden (G ’73), in loving memory of his wife Monique (1950-2009). ................................................................................... -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Booklet & CD Design & Typography: David Tayler Cover Art: Adriaen Coorte

Voices of Music An Evening with Bach An Evening with Bach 1. Air on a G string (BWV 1069) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) 2. Schlummert ein (BWV 82) Susanne Rydén, soprano 3. Badinerie (BWV 1067) Dan Laurin, voice flute 4. Ich folge dir gleichfalls (St. John Passion BWV 245) Susanne Rydén, soprano; Louise Carslake, baroque flute 5. Giga (BWV 1004) Dan Laurin, recorder 6. Schafe können sicher weiden (BWV 208) Susanne Rydén, soprano 7. Prelude in C minor (BWV 871) Hanneke van Proosdij, harpsichord 8. Schlafe mein Liebster (BWV 213) Susanne Rydén, soprano 9. Prelude in G major (BWV 1007) David Tayler, theorbo 10. Es ist vollbracht (St. John Passion BWV 245) Jennifer Lane, alto; William Skeen, viola da gamba 11. Sarabanda (BWV 1004) Elizabeth Blumenstock, baroque violin 12. Kein Arzt ist außer dir zu finden (BWV 103) Jennifer Lane, alto; Hanneke van Proosdij, sixth flute 13. Prelude in E flat major (BWV 998) Hanneke van Proosdij, lautenwerk 14. Bist du bei mir (BWV 508) Susanne Rydén, soprano 15. Passacaglia Mein Freund ist mein J.C. Bach (1642–1703) Susanne Rydén, soprano; Elizabeth Blumenstock, baroque violin Notes The Great Collectors During the 1980s, both Classical & Early Music recordings underwent a profound change due to the advent of the Compact Disc as well as the arrival of larger stores specializing in music. One of the casualties of this change was the recital recording, in which an artist or ensemble would present an interesting arrangement of musical pieces that followed a certain theme or style—much like a live concert. Although recital recordings were of course made, and are perhaps making a comeback, most recordings featured a single composer and were sold in alphabetized bins: B for Bach; V for Vivaldi. -

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker July 8-15, and July 15-22 Connecticut College, New London CT Music of France and the Low Countries Largest recorder program in U.S. Expanded vocal programs Renaissance reeds and brass New London Assembly Festival Concert Series Historical Dance Viol Excelsior www.amherstearlymusic.org Amherst Early Music Festival 2018 Week 1: July 8-15 Week 2: July 15-22 Voice, recorder, viol, violin, cello, lute, Voice, recorder, viol, Renaissance reeds Renaissance reeds, flute, oboe, bassoon, and brass, flute, harpsichord, frame drum, harpsichord, historical dance early notation, New London Assembly Special Auditioned Programs Special Auditioned Programs (see website) (see website) Baroque Academy & Opera Roman de Fauvel Medieval Project Advanced Recorder Intensive Ensemble Singing Intensive Choral Workshop Virtuoso Recorder Seminar AMHERST EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL FACULTY CENTRAL PROGRAM The Central Program is our largest and most flexible program, with over 100 students each week. RECORDER VIOL AND VIELLE BAROQUE BASSOON* Tom Beets** Nathan Bontrager Wouter Verschuren It offers a wide variety of classes for most early instruments, voice, and historical dance. Play in a Letitia Berlin Sarah Cunningham* PERCUSSION** consort, sing music by a favorite composer, read from early notation, dance a minuet, or begin a Frances Blaker Shira Kammen** Glen Velez** new instrument. Questions? Call us at (781)488-3337. Check www.amherstearlymusic.org for Deborah Booth* Heather Miller Lardin* Karen Cook** Loren Ludwig VOICE AND THEATER a full list of classes by May 15. Saskia Coolen* Paolo Pandolfo* Benjamin Bagby** Maria Diez-Canedo* John Mark Rozendaal** Michael Barrett** New to the Festival? Fear not! Our open and inviting atmosphere will make you feel at home Eric Haas* Mary Springfels** Stephen Biegner* right away. -

The Development of the Flute As a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era

Musical Offerings Volume 2 Number 1 Spring 2011 Article 2 5-1-2011 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Anna J. Reisenweaver Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Musicology Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Reisenweaver, Anna J. (2011) "The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era," Musical Offerings: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2011.2.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol2/iss1/2 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Document Type Article Abstract As one of the oldest instruments known to mankind, the flute is present in some form in nearly every culture and ethnic group in the world. However, in Western music in particular, the flute has taken its place as an important part of musical culture, both as a solo and an ensemble instrument. The flute has also undergone its most significant technological developments in Western musical culture, moving from the bone keyless flutes of the Prehistoric era to the gold and silver instruments known to performers today. -

EC-Bach Perfection Programme-Draft.Indd

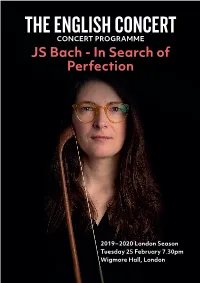

THE ENGLISH CONCE∏T 1 CONCERT PROGRAMME JS Bach - In Search of Perfection 2019 – 2020 London Season Tuesday 25 February 7.30pm Wigmore Hall, London 2 3 WELCOME PROGRAMME Wigmore Hall, More than any composer in history, Bach The English Concert 36 Wigmore Street, Orchestral Suite No 4 in D Johann Sebastian Bach is renowned Laurence Cummings London, W1U 2BP BWV 1069 Director: John Gilhooly for having frequently returned to his Guest Director / The Wigmore Hall Trust own music. Repurposing and revising it Bach Harpsichord Registered Charity for new performance contexts, he was Sinfonia to Cantata 35: No. 1024838. Lisa Beznosiuk Geist und Seele wird verwirret www.wigmore-hall.org.uk apparently unable to help himself from Flute Disabled Access making changes and refinements at Bach and Facilities Tabea Debus Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D every level. Recorder BWV 1050 Tom Foster In this programme, we explore six of Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking INTERVAL Organ venue. No recording or photographic Bach’s most fascinating works — some equipment may be taken into the Sarah Humphrys auditorium, nor used in any other part well known, others hardly known at of the Hall without the prior written Bach Recorder permission of the Hall Management. all. Each has its own story to tell, in Sinfonia to Cantata 169: Wigmore Hall is equipped with a Tuomo Suni ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users receive illuminating Bach’s working processes Gott soll allein mein Herze haben clear sound without background Violin and revealing how he relentlessly noise. Patrons can use the facility by Bach switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. -

Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra Barthold Kuijken, Artistic Director & Conductor Toma Iliev, Maria Romero, Stephanie Raby, Violins ______

Three Hundred Ninety-Eighth Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Early Music Institute IndyBaroque Music The Allen Whitehill Clowes Series Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra Barthold Kuijken, Artistic Director & Conductor Toma Iliev, Maria Romero, Stephanie Raby, Violins _______________________ The Colorful Telemann From Armide (1686) . Jean-Baptiste Lully Ouverture (1632-1687) Passacaille Overture in E Minor, TWV 55:e3 .......... Georg Philipp Telemann Ouverture (1681-1767) Les Cyclopes Menuet Galimatias en rondeaux Hornpipe _________________ Auer Concert Hall Saturday Afternoon January Nineteenth Four O’Clock music.indiana.edu Concerto in F Major, RV 551 ................... Antonio Vivaldi Allegro (1678-1741) Andante Allegro Toma Iliev, Maria Romero, Stephanie Raby, Violins Malin Sandell, Cello Bernard Gordillo, Harpsichord Intermission Suite from Dardanus (1739) ................ Jean-Philippe Rameau Ouverture (1683-1764) Air pour les Plaisirs I Air pour les Plaisirs II Air gracieux Tambourins I and II Air vif Rigaudons I and II Air gay en rondeau Menuets I and II Tambourins I and II Sommeil: Rondeau tendre Air très vif Calme des Sens: Air tendre Gavotte vive Chaconne ___________________ Barthold Kuijken is the world’s leading performer on the Baroque flute. He regularly appears with such early music specialists as his brothers, Sigiswald Kuijken, violin, and Wieland Kuijken, viol, as well as with Paul Dombrecht, oboe, and harpsichordist Bob van Asperen. He performed frequently with the late harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt. Born in Belgium in 1949, Kuijken began his conservatory studies on the modern flute in Bruges and Brussels, where he played with the contemporary music ensemble Musiques Nouvelles. He discovered the Baroque flute on his own while a student in Brussels. -

Nicola Benedetti, Violin Venice Baroque Orchestra

Friday, February 24, 2017, 8pm Zellerbach Hall r e l w o F n o m i S Nicola Benedetti, violin Venice Baroque Orchestra Gianpiero Zanocco, concertmaster Giacomo Catana, first violin Mauro Spinazzè, first violin Francesco Lovato, first violin Giorgio Baldan, second violin David Mazzacan, second violin Giuseppe Cabrio, second violin Claudio Rado, second violin Alessandra Di Vincenzo, viola Meri Skejic, viola Massimo Raccanelli Zaborra, cello Federico Toffano, cello Alessandro Pivelli, double bass Ivano Zanenghi, lute Lorenzo Feder, harpsichord PROGRAM Baldassare GALUPPI (1706 –1785) Concerto a Quattro No. 2 in G Major for Strings and Continuo Andante Allegro Andante Allegro assai Charles AVISON (1709 –1770) Concerto Grosso No. 8 in E minor aer Domenico Scarlatti Adagio Allegro Amoroso Vivace Francesco GEMINIANI (1687 –1762) Concerto Grosso No. 12 in D minor, aer Corelli’s Violin Sonata in D minor, Op. 5, No 12, La Folia [Adagio – Allegro – Adagio – Vivace – Allegro – Andante – Allegro – Adagio – Adagio – Allegro – Adagio – Allegro] Antonio VIVALDI (1678 –1741) Concerto for Violin, Strings, and Continuo in D Major, R. 212a, Fatto per la solennità della S. Lingua di St. Antonio in Padua Allegro Largo Allegro INTERMISSION VIVALDI e Four Seasons for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 8, Nos. 1-4 SPRING : (R. 269) : Allegro – Largo e pianissimo sempre – Danza Pastorale (Allegro) SUMMER : (R. 315) : Allegro non molto – Adagio – Presto AUTUMN : (R. 293) : Allegro – Adagio – Allegro WINTER : (R. 297) : Allegro non molto – Largo – Allegro Opposite: photo by Simon Fowler PROGRAM NOTES Concerto a Quattro No. 2 in G Major (“church sonata,” a musical type oen used dur - for Strings and Continuo ing services in Italy)—four succinct movements Baldassare Galuppi disposed slow –fast –slow –fast, a fondness for Baldassare Galuppi’s importance in the 18th- contrapuntal textures—as well as encroaching century’s radical evolution of musical taste is Classicism—clear phrasing, symmetrical melo - in almost precisely inverse proportion to his no - dies, largely diatonic harmonies. -

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Saturday, March 10, 2012, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir Ton Koopman, conductor soloists Teresa Wakim, soprano Bogna Bartosz, alto Tilman Lichdi, tenor Klaus Mertens, bass PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Mass in B minor, BWV 232 for soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists, chorus and orchestra i. missa Crucifixus Kyrie Et resurrexit Christe Et in Spiritum Sanctum Kyrie Confiteor Gloria Et expecto Laudamus te Gratias INTERMISSION Domine Deus Qui tollis iii. sanctus Qui sedes Sanctus Quoniam Cum Sancto Spiritu iv. osanna, benedictus, agnus dei Osanna ii. symbolum nicenum Benedictus Credo Osanna Et in unum Dominum Agnus Dei Et incarnatus est Dona nobis pacem This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Michele and Kwei Ü. Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 11 ORCHESTRA ROSTER CHOIR ROSTER AMSTERDAM BAROQUE ORCHESTRA AMSTERDAM BAROQUE CHOIR Ton Koopman, conductor soloists Teresa Wakim, soprano Catherine Manson concertmaster Bogna Bartosz, alto Joseph Tan violin 1 Tilman Lichdi, tenor John Meyer violin 1 Klaus Mertens, bass Anna Eunjung Ryu violin 1 soprano Persephone Gibbs violin 1 Caroline Stam David Rabinovich violin 2 Dorothee Wohlgemuth Marc Cooper violin 2 Andrea Van Beek Ann Roux violin 2 Els Bongers Liesbeth Nijs violin 2 Vera Lansink Esther Ebbinge Emilia Benjamin viola Gela Birckenstaedt Laura Johnson viola Isabel Delemarre Werner Matzke cello Margareth Iping (doubling alto) Robert Smith cello Michele Zeoli -

VIOLINIST ANDREW MANZE and the ENGLISH CONCERT ENLIVEN EARLY MUSIC SERIES Chicago Period Violinist Andrew Manze Will Lead the English Concert on Friday, Nov

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cathy Sweitzer Director of Communications 773 / 834-7965 presents Tickets: 773 / 702-8068 October 3, 2005 VIOLINIST ANDREW MANZE AND THE ENGLISH CONCERT ENLIVEN EARLY MUSIC SERIES chicago Period violinist Andrew Manze will lead The English Concert on Friday, Nov. 11, 2005, as The University of Chicago Presents Early Music Series continues in Mandel Hall. The program will feature everything from a Bach Suite to Biber’sSonata Representativa, serving up the sounds of a cat, a frog, a cuckoo, a hen, a nightingale and a musketeer. the university of Manze will lead the sextet and comment from the stage in what has come to be his signature style -- equal parts scholarship and irrepressible wit. PROGRAM: “Baroque Untamed” Biber Part III Mensa Sonora Pachelbel Suite in F-sharp Minor Jenkins Pavan à 4 Castello Sonata per stromenti d’arco Purcell Fantasia à 4 Biber Two sonatas from Fidicinium sacro-profanum Biber Sonata Representativa Office of Professional Concerts 5720 S. Woodlawn Avenue J.S. Bach Suite in D Major, reconstructed from BWV1068 Chicago, Illinois 60637 773/702-8068 773/834-5888 fax [email protected] chicagopresents.uchicago.edu howard mayer brown early music series chamber music series saint paul chamber orchestra series artists-in-residence series The University of Chicago Presents 2005-2006 Season - Page 2 ABOUT ANDREW MANZE AND THE ENGLISH CONCERT Kent-born violinist Andrew Manze brings knowledge, experience and passion to his role as Director of The English Concert. While studying Classics at Cambridge, friends gave him a baroque violin to play.