Literature, Theory and the History of Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

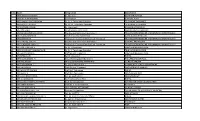

S.No Name Designation Department 1 MRS.JESSIE RAJASEKAR Sr

S.No Name Designation Department 1 MRS.JESSIE RAJASEKAR Sr. Secretary SECRETARIAL POOL 2 MRS.RUTH RAJKUMARI Secretary III CLERICAL POOL 3 MRS.VIMALA BACKIAROYAN Sr. Gr. I Telephone Operator TELEPHONE EXCHANGE 4 MRS.APPOLONI DOSS Sr. Gr. III Telephone Operator TELEPHONE EXCHANGE 5 MRS.ESTHER AARON Sr. Librarian II COLLEGE OF NURSING 6 MS.CYNTHIA D Sr.Sel Gr.ECG Technician I CARDIOLOGY TECHNICIAN 7 MS.SIGAMANISELVAKUMARI Medical Lab Technician Instructor I TRANSFUSION MEDICINE AND IMMUNO HAEMATOLOGY 8 MS.VIJAYALAKSHMI B Sr.Sel.Gr.Clinical Biochemist CLINICAL BIOCHEMISTRY 9 MRS.SHANTHI R Instructor I Graduate Medical Lab Technician TRANSFUSION MEDICINE AND IMMUNO HAEMATOLOGY 10 MRS.RACHEL EVELYN Medical Lab Technician Instructor I GENERAL PATHOLOGY 11 MR.SURENDAR SINGH G Instructor I Graduate Medical Lab Technician TRANSFUSION MEDICINE AND IMMUNO HAEMATOLOGY 12 MR.KARTHIGEYAN V Sr. Gr. I Electrician ENGINEERING ELECTRICAL 13 MRS.MARGARET ANBUNATHAN Sr. Gr. I Telephone Operator TELEPHONE EXCHANGE 14 MR.GOVINDARAJI S. Staff Gr Asst. Engineer I ENGINEERING ELECTRICAL 15 MS.NIRMALA R Sel Gr.Librarian I RUHSA 16 MRS.KONDAMMA N. House Keeping Attendant Gr. I PM OFFICE RELIEF POOL 17 MR.YESUDOSS T SR. HOUSE KEEPING ATTENDANT NURSING SERVICE 18 MS.THIRUMAGAL E Sr. Sel. Gr.Pharmacist I COMMUNITY HEALTH DEPARTMENT 19 MR.NAGARAJ N. Staff Gr Asst. Engineer I ENGINEERING PLANNING 20 MR.MUNIRATHINAM S Staff Gr I Technician RUHSA 21 MR.RAVI K S Staff Gr II Technician OPHTHALMOLOGY 22 MR.JOHN BASKARAN B. Sel. Gr. Staff Clerk I MICROBIOLOGY 23 MR.JAYAKUMAR K. Sr.Gr.Artisan(Non ITI) II RUHSA 24 MRS.SHIRLEY ANANDANATHAN External Designation CENTRE FOR STEM CELL RESEARCH 25 MR.NARASIMHAN V Staff Gr. -

Christian Medical College Vellore This Prospectus Is Common to All Courses Around the Year and Needs to Be Read with the Appropriate Admission Bulletin for the Course

Admissions 2018-2019 Christian Medical College Vellore This prospectus is common to all courses around the year and needs to be read with the appropriate admission bulletin for the course ALL COURSES AND ADMISSIONS TO OUR COLLEGE ARE SUBJECT TO APPLICABLE REGULATIONS BY UNIVERSITY/GOVERNMENT/MEDICAL COUNCIL OF INDIA/NATIONAL BOARD OF EXAMS NO FEE OR DONATION OR ANY OTHER PAYMENTS ARE ACCEPTED IN LIEU OF ADMISSIONS, OTHER THAN WHAT HAS BEEN PRESCRIBED IN THE PROSPECTUS THE GENERAL PUBLIC ARE THEREFORE CAUTIONED NOT TO BE LURED BY ANY PERSON/ PERSONS OFFERING ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE COURSES CONDUCTED BY US SHOULD ANY PROSPECTIVE CANDIDATE BE APPROACHED BY ANY PERSON/PERSONS, THIS MAY IMMEDIATELY BE REPORTED TO THE LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES FOR SUITABLE ACTION AND ALSO BROUGHT TO THE NOTICE OF OUR COLLEGE AT THE ADDRESS GIVEN BELOW OUR COLLEGE WILL NOT BE RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY CANDIDATES OR PARENTS DEALING WITH SUCH PERSONS CORRESPONDENCE All correspondence should refer to the Application number or to the Hall Ticket number and be addressed to: The Registrar Christian Medical College, Vellore-632002 Tamil Nadu, India Phone: (0416)2284255 Fax: (0416) 2262788 Email: [email protected] Website: http://admissions.cmcvellore.ac.in PLEASE NOTE: WE DO NOT ADMIT STUDENTS THROUGH AGENTS OR AGENCIES Important Information: “The admission process contained in this Bulletin shall be subject to any order that maybe passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court or the High Court in the proceedings relating to the challenge to the NEET, common counselling or -

Rumour Has It Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RUMOUR HAS IT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jill Mansell | 416 pages | 25 Jun 2009 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755328192 | English | London, United Kingdom Rumour Has it PDF Book Young Katharine. An expansion of who the singer is, she moves on having destroyed the man who left her, taking for herself the woman he believed was his. Warner Brothers claims to be releasing the film during the Christmas movie season because it's the perfect time of the year for this kind of story. Production Co: Warner Bros. But Costner is a dead weight in any comedy, and his all-important confrontation with MacLaine is lacklustre and unfunny. Add the first question. Check out our gallery. Contribute to this page Edit page. Quotes Katharine : You know, I still pick up the paper every day just to read your obituaries. Drishyam 2 is produced by Antony Perumbavoor, under the banner Aashirvad Cinemas. IMDB: 5. Edit Storyline Hunky NY lawyer Jeff Daly finally got engaged to fickle Sarah Huttinger, who presents him to her Pasadena family, who all soon take to him, for her sister's wedding to Scott. His real name is Beau Burroughs Kevin Costner , a lonely multi-millionaire who admits to Sarah that he slept with both her mother and grandmother. It was a different sort of combination that really hit the spot. Blake Burroughs: Wanna have sex? The sources close to the project suggest that the post-production works of the Mohanlal starrer are nearing the final stage, and the teaser release is definitely on cards. Rumour Has It is a song about the bad things that rumors can do to a relationship. -

Page5- 1 Entertainment.Qxd (Page 1)

ENTERTAINMENT z Friday z May 7, 2021 5 Ajay Devgn to reprise the role of Meera Desothale opens up about her journey! Vijay Salgaonkar from Drishyam, ctor Meera Deosthale came to Mumbai with a makers acquires the rights of dream and a lot of apprehension in her heart Aabout how the city and the industry would be to her. However, a few years down the line, and Meera has Drishyam 2! already made quite a name for herself through her shows Udaan and Vidya. Talking about how it all began for her, Oats Mini Uttapam she says, “I am from a small town and I had a lot of inhi- bitions about Mumbai and the entertainment industry. But since the time I came here, I had the support of my mom, who has been living with me. She is always there and her guidance has been incredible. I remember she would accompany me when I would go for 3-4 auditions in a day and we would only return home at night. But Udaan, it has been a bit easier,” she says. In fact, life changed after Udaan quite drastically, she says, “Udaan was a great show and it made me who I am. I remember my mom would often get calls after my episodes in Udaan. My parents were also apprehensive She said yes, but that I needed to work on myself. After about me being part of the industry, but seeing me in that, I got my dad to enroll me in an acting course. I was jay Devgn starrer Drishyam was a suspense drama with a nail-bit- Udaan actually helped them understand my career so focussed and have been since then. -

Multibagger Stock Advisor for Multibagger Stock Advisor Hnis, Check Proven Past Multibaggershares.Com Performance Here

11/21/2017 Nilekanis pledge half of wealth to charity | Nandan Nilekani | Rohini Nilekani | Bill Gates | Azim Premji | Onmanorama Multibagger Stock Advisor for Multibagger Stock Advisor HNIs, Check Proven Past multibaggershares.com Performance Here Make Us Your Home Page Sign In Register Follow Us On Last Updated Tuesday November 21 2017 12:15 PM IST E paper Manoramaonline Manoramanews TV Radio Mango Chuttuvattom Gulf Blogs Manorama Products Home News Sports Business Wellness Lifestyle Entertainment Travel Food Slide Show Women AllHome SectionsNews Nation Nilekanis pledge half of wealth to charity Nilekanis pledge half of 1 Tweet Like S wealth to charity Tuesday 21 November 2017 11:48 AM IST by PTI Share Email Print Text Size OUR PICK Ads By Datawrkz Pranav Mohanlal stuns Nandan Nilekani recently returned to Infosys as Non-Executive Chairman after the exit of Vishal Sikka as Infosys CEO. File Photo director by daring stunts without dupe Bengaluru: Infosys co-founder and tech billionaire Pranav's act of performing dangerous stunts for RELATED STORIES Nandan Nilekani and his wife Rohini Nilekani have his debut film Aadi, directed by Jeethu Joseph, is now gaining wide... joined 'The Giving Pledge', an elite network of the Inspired by India: Bill Gates praises PM Modi, again worlds wealthiest individuals committing half their • 'Tumhari Sulu' review: strong performances wealth to philanthropy. elevate this light-hearted film The Giving Pledge website uploaded Nilekanis' letter • Hadiya's father stops state women's commission chief from meeting daughter signing up for the cause. The letter said, "We thank Bill and Melinda for creating this unique opportunity to realise a • No missing these 'Miss Worlds' from India moral aspiration inspired by the Bhagwad Gita "Karmanye Va dhikaraste Ma Phaleshu • IAS officer arrested in Rajasthan for rape Kadachana, Ma karma phalaheturbhurma Te Sangostvakarmani." • This 3,500 sqft holiday home in Kumily is "We have a right to do our duty,but no automatic right to the fruits from the doing. -

Destination Promotion Through Malayalam Cinema: a Study on the Idukki District of Kerala

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-11, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Destination Promotion through Malayalam Cinema: A Study on the Idukki District of Kerala Bijith M Balan Master of Journalism and Mass Communication Department of Visual Media, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi Abstract: This study focuses on the portrayal of successful attempt that continues till today. This is Idukki district of Kerala in recent Malayalam films mostly evident in the use of iconic cityscapes of and its role in the promotion of tourism in the Kolkata, Mumbai, Delhi etc. and the exotic hill region. It aims at finding a relation between stations around India such as Kashmir, Darjeeling, previous movies where the district is undisclosed to and Shimla, as well as the rich forest reserves of the audiences and the lately released ones where both northern and southern India. In south Indian the possibility of the location is used to its cinema mainly Tamil and Malayalam film maximum extent that has led to a booming tourism industries this use of location is most prominent as industry in Idukki district. Films having acquired a most of them are musicals where the carefully greater role in today’s social life also tend to have choreographed music and dance sequences blend in a tremendous influence among the people in even with the setting used. Since the focus of this choosing the preferred destinations for their research is about the use of location in movies and leisurely visits. It has become a growing trend its impact on the tourism sector, the Malayalam among tourists to visit places which are being used film industry is chosen because of a recent surge in as filming locations. -

Marketing of Malayalam Films Through New Media

MARKETING OF MALAYALAM FILMS THROUGH NEW MEDIA ANMI ELIZABETH SABU Registered Number: 1424024 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Communication Studies CHRIST UNIVERSITY Bengaluru 2016 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies ii CHRIST UNIVERSITY Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Anmi Elizabeth Sabu Registered Number: 1424024 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ [CHANDRASEKHAR VALLATH] _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ iii iv I, Anmi Elizabeth Sabu, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: v vi CHRIST UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT Marketing of Malayalam Films through New Media Anmi Elizabeth Sabu The research studies the marketing strategies used by Malayalam films through New Media. In this research new media includes Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Whatsapp and instagram. -

Language Wise List of the Feature Films Indian/Foreign (Digital & Video)

Language wise List of the feature films Indian/Foreign (Digital & Video) Certified during period (01/01/2019 - 01/12/2019) Certified Type Of Film Certificate Sr. No Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/ (Video/Digital/C Producer Name Production House Type Length elluloid) ARABIC ARABIC WITH ENGLISH 1 YOMEDDINE DFL/1/16/2019-MUM 26 March 2019 99.2 Digital WILD BUNCH - U SUBTITLES CAPHARNAUM ( Arabic With English Capharnaum Film 2 DFL/3/25/2019-MUM 02 May 2019 128.08 Digital - A CHILDREN OF CHAOS) Subtitles Ltd BVI CAPHARNAUM Arabic with English Capharnaum Film 3 VFL/2/448/2019-MUM 13 August 2019 127.54 Video - UA (CHILDREN OF CHAOS) Subtitles Ltd BVI ASSAMESE DREAM 1 KOKAIDEU BINDAAS Assamese DIL/1/1/2019-GUW 14 February 2019 120.4 Digital Rahul Modi U PRODUCTION Ajay Vishnu Children's Film 2 GATTU Assamese DIL/1/59/2019-MUM 22 March 2019 74.41 Digital U Chavan Society, India ASSAMESE WITH Anupam Kaushik Bhaworiya - The T- 3 BORNODI BHOTIAI DIL/1/5/2019-GUW 18 April 2019 120 Digital U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Borah Posaitives ASSAMESE WITH Kunjalata Gogoi 4 JANAKNANDINI DIL/1/8/2019-GUW 25 June 2019 166.23 Digital NIZI PRODUCTION U ENGLISH SUBTITLES Das SKYPLEX MOTION Nazim Uddin 5 ASTITTWA Assamese DIL/1/9/2019-GUW 04 July 2019 145.03 Digital PICTURES U Ahmed INTERNATIONAL FIREFLIES... JONAKI ASSAMESE WITH 6 DIL/3/2/2019-GUW 04 July 2019 93.06 Digital Milin Dutta vortex films A PORUA ENGLISH SUBTITLES ASSAMESE WITH 7 AAMIS DIL/2/4/2019-GUW 10 July 2019 109.07 Digital Poonam Deol Signum Productions UA ENGLISH SUBTITLES ASSAMESE WITH 8 JI GOLPOR SES NAI DIL/3/3/2019-GUW 26 July 2019 94.55 Digital Krishna Kalita M/S. -

HM 05 MAY Page 10.Qxd (Page 1)

www.himalayanmail.com 10 JAMMU ☯ WEDNESDAY ☯ MAY 05, 2021 ENTERTAINMENT The Himalayan Mail Packed with upbeat chartbusters, Full jukebox of Salman Kunal Kohli’s Ramyug gets Khan’s Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai out now fter grand success of first two songs a big thumbs up Afrom the film, makers of Radhe: Your ack in the 90’s, Most Wanted Bhai have re- Sunday mornings leased the complete jukebox Bmeant watching from the film, which also in- Ramanand Sagar’s ‘Ra- cludes two unreleased mayan’ on television with tracks. family and friends. Each person has varied memories The jukebox consists of or experiences attached to the current rage Seeti Maar, this epic and multiple rendi- the chartbuster featuring tions of this story - be it Salman Khan and Disha dance dramas, the Ram -Lila Patani. The song has been or mythological shows/films topping the charts since it bring back a unique connec- released and fast nearing tion to this ancient literary the 100 Million views mile- text. Retelling the story of stone. Dil De Diya, second this primordial era for young song from the film, marks and old audiences is the up- another super-hit associa- with the audio out now, an- Payal Dev, Sajid and Ash and Reel Life Production coming Kunal Kohli directo- tion between Salman Khan ticipation from the song is King and lyrics by Shabbir Pvt. limited. The movie rial - MX Original Series of my most adored charac- Sagar's Ramayan taught me even now. No one would and Jacqueline Fernandez, at an all-time high. -

Three Capitals for Andhra, Hints Jagan

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. APENG/2018/764698 Established 1864 Published From OPINION 6 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW GLOBAL FM SETS RS 1.1L CR MONTHLY INDIA OUT BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH WARNING TO SAVE SERIES BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN GST COLLECTION TARGET HYDERABAD *Late City Vol. 2 Issue 47 VIJAYAWADA, WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 18, 2019; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable RAJINIKANTH: I WANT TO PLAY THE ROLE OF A TRANSGENDER { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com Bihar woman, AP House set on fire adjourned after failed Three capitals for Andhra, hints Jagan sine die rape bid, dies Visakhapatnam may be executive capital, Legal capitalin Kurnool and Legislative capital in Vijayawada PNS n VIJAYAWADA PNS n PATNA From TDP’s Singapore model to YSRCP’s South Africa style, decisions help ruling pary gain political capital Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly was adjourned sine The 23-year old woman, who PNS n VIJAYAWADA die by Speaker Tammineni was set on fire after a failed Sitaram. rape bid in Bihar's Muzaff- Ending the uncertainty over The seven day assembly arpur district on December 7, future of Amaravati as Andhra Why this much hatred against session has passed the Disha died here on Monday night. Pradesh capital, Chief Minister Bill, which seeks expeditious She was undergoing treat- Y. S. Jagan Mohan Reddy on trial of cases pertaining to ment in Patna'a Appolo hos- Tuesday said the state may crime against women and pital after receiving 80 per have three capitals with exec- Amaravati, asks Chandrababu children. -

From the Report to Charlie's Angels, Hollywood Has Shown Us a String Of

Community Community Nearsightedness Attended happens when by over P4cornea — the P16 600 people. clear front surface of Indonesian products the eye — is curved too exhibition ‘Indonesia much or when the eye Expo 2019’ comes is longer than normal. to a close. Friday, November 22, 2019 Rabia I 25, 1441 AH Doha today: 180 - 240 Clarion call COVER STORY From The Report to Charlie’s Angels, Hollywood has shown us a string of heroes calling out corruption this year. P2-3 CUISINE SHOWBIZ Suppli vs Dwayne Johnson opens up about Arancini. possibility of third Jumanji. Page 6 Page 15 2 GULF TIMES Friday, November 22, 2019 COMMUNITY COVER STORY Standing up for the count PRAYER TIME Fajr 4.35am With upper-level malfeasances all over the place and Shorooq (sunrise) 5.57am Zuhr (noon) 11.21am Asr (afternoon) 2.25pm citizens desperate for someone to do something, Maghreb (sunset) 4.45pm Isha (night) 6.15pm the past year or so has seen an odd spike in movies USEFUL NUMBERS about people speaking truth to power, no matter the consequences, writes Charles Bramesco Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 44593363 Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post -

Problem Solving in Nishikant Kamat's Movie Drishyam

AICLL KnE Social Sciences The 1st Annual International Conference on Language and Literature Volume 2018 Conference Paper Problem Solving in Nishikant Kamat’s Movie Drishyam Yoeanita and Dika Kurniadi Master’s Program, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Islam Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia Abstract This research is related to the process of problem solving that happened in the Nishikant Kamat movie’s Drishyam. The purpose of this research is to find what kinds of problem solving done in this movie and how those kinds implemented in the movie. The theory used in this research was the problem-solving theory proposed by Redoni (2017) because this theory divides the kinds of problem solving into four categories they are: comprehend the problem, arrange the plan, run the plan, and test and retest the plan that was studied by using Khotari (1990) qualitative method. The result of this research was the actor could comprehend the problems that make them Corresponding Author: Yoeanita have good strategies to arrange some plans and run it. After that, the actor tests and [email protected] re-tests all his plans to make the problem solved well. This research is important for Received: 13 March 2018 people getting into problem as they will find easy to solve problems by knowing the Accepted: 10 April 2018 kinds of problem solving. Published: 19 April 2018 Publishing services provided by Keywords: Problem Solving, Problem Comprehension, Arrangement Problem, Test Knowledge E and Re-test Planning Yoeanita and Dika Kurniadi. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons 1. Introduction Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the Movie is a type of visual communication which uses moving pictures and sound to original author and source are tell stories or inform [2].